Social information processing (theory)

- For the information processing that occurs in large-scale and typically networked groups, see Social information processing.

Social information processing theory (SIP) is an interpersonal communication theory developed by Joseph Walther in 1992[1] explaining how people get to know one another online, without nonverbal cues, and how they develop and manage relationships in the computer-mediated environment.[1][2] However, online interpersonal relationship development may require more time to develop than traditional face-to-face (FTF) relationships. Once established, online personal relationships may demonstrate the same relational dimensions and qualities as FTF relationships. Online relationships may help facilitate relationships that would not have formed in the face-to-face world due to intergroup differences, geographic challenges, etc.

A theory of online communication

The nature of online interaction is a highly studied field that has experienced both positive and negative media ecology. Various electronic media theories offer explanations for the difference between computer-mediated communication (CMC) and Face-to-Face communication, including the social presence theory, media richness theory, and lack of social context cues.[3] Social presence theory suggests that CMC deprives users of the sense that another person is involved in the interaction. To the extent that we end up feeling like nobody is there, our communication becomes impersonal, individualistic and task-oriented. Media richness theory classifies each communication medium according to the complexity of the messages it can handle efficiently. It claims that CMC band-width is too narrow to convey rich relational messages. The third theory focuses on the lack of social context cues in online communication. The theory claims that CMC users have no clue as to their relative status, and norms for interaction are not clear, so people tend to become more self-centered and less inhibited. The result is increased flaming – hostile language that zings its targets and creates a toxic climate for relational growth on the internet.[4] All of these theories share a cues filtered out interpretation of CMC that regards lack of nonverbal cues as a fatal flaw for using the medium for relationship development. More recent theories have developed an increasingly optimistic view of online communication, explaining how those who interact online are highly capable of creating and maintaining impressions and relationships with others online.

Now at Nanyang Technological University, Walther claims that CMC users can adapt to this restricted medium and use it effectively to develop close relationships. He argued that if there was an opportunity for sufficient exchange of social messages and adequate relationship growth, as goes with face-to-face communication, so goes CMC. Walther built Social Information Processing (SIP) upon the larger notion of CMC or nonverbal communication transactions that occur through the use of two or more networked computers.[5] While the term has traditionally referred to those communications that occur via computer-mediated formats (e.g., instant messages, e-mails, chat rooms), it has also been applied to other forms of text-based interaction such as text messaging.[6] Walther understood that the mediated nature of online communication required a new theory to describe it.[1]

CMC vs Face-to-Face

Social information processing theory endorses online communication. SIP proposes that despite the inherent lack of cues found in the nonverbal communication of online interactions, there 6.3are many other ways for people to create and process personal, or individualized, information.[7] Walther believes relationships grow only to the extent that parties first gain information about each other and use that information to form interpersonal impressions of who they are. With these impressions in mind, the interacting parties draw closer if the two parties both like the others images being presented. Walther acknowledges that nonverbal cues are filtered out of the interpersonal information that we send and receive through CMC. Unlike cues filtered out, he doesn’t think this loss is necessarily fatal to the development of the relationship. This is called Impression formation—the composite mental image one person forms of another.[4]

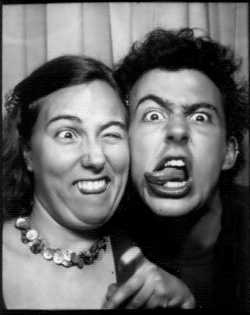

Walther argues nonverbal cues (such as those seen here) can be exchanged for verbal cues in CMC to build intimacy over time.

Several aspects - such as replaced cues, asynchronous communication, insightful interaction, desire for impression management and maintained partner affinity - are all in support of social information processing as a comparable, if not improved, alternative of face-to-face communication (see hyperpersonal model). Similar to face-to-face interactions, people motivated in online interactions with others also wish to "reduce interpersonal uncertainty, form impressions, and develop affinity."[1] Walther argues verbal cues can be replaced with nonverbal cues over CMC and has published experimental support for this claim. Here, affection expressed verbally online was compared to verbal synchronous offline communication and found to be equivalent across settings.[8] Walther also found that, proportionately, CMC partners ask more questions and disclose more about themselves than do their face-to-face counterparts. In this way, CMC may actually improve or assist FtF interactions.[9]

"A SIP Instead of a Gulp"

Time is cited as the key determinant as to whether nonverbal cues achieve the same amount of intimacy as verbal cues in FtF communication.[3] Walther argues CMC communication can lead to equally strong relationships as FtF with more time (see hyperpersonal model).[3] Walther highlights two features of CMC that provide a rationale for SIP Theory: Verbal Cues and Extended Time. Verbal Cues refers to how CMC users can create fully formed impressions of others based solely on the linguistic content of computer-mediated messages. Extended Time means, that the communication exchange rate through CMC is much slower than face-to-face; therefore, the impressions are formed at a much slower rate.[4] Even though CMC takes longer than face-to-face interactions, there is no reason to believe that CMC relationships will be any weaker than those developed face-to-face. The "SIP" acronym refers to someone slowly "sipping" a glass of water, or having a CMC relationship. Here the impressions are formed at a slower rate. In contrast, if a person were to gulp the water, it would be like having a face-to-face conversation. The verbals and nonverbals are flooded into the conversation, resulting in a faster impression. However, either way, the water is being consumed, so the result is the same quantity and quality of water, or interpersonal knowledge. CMC just accumulates at a slower rate.

Intimacy

Several theorists have explored the differences in intimacy developed through CMC versus face-to-face communication. Walther is convinced that the length of time that CMC users have to send their messages is the key factor that determines whether their messages can achieve the same level of intimacy that others develop face-to-face. Over an extended period the issue is not the amount of social information that can be conveyed online; rather, it’s the rate at which the information builds up. Any message spoken in person will take at least four times longer to communicate through CMC. When comparing 10 minutes of face-to-face conversation with 40 minutes of CMC, there was no difference in partner affinity between the two modes. Anticipated future interaction is a way of extending physiological time, which gives the likelihood of future interaction and motivates CMC users to develop a relationship. Relational messages provide interactants with information about the nature of the relationship, the interactants' status in the relationship, and the social context within which the interaction occurs.[10] The “Shadow of the future” motivates people to encounter others on a more personal level. A chronemic cue is a type of nonverbal cue not filtered out of CMC and indicates how one perceives, uses, or responds to issues of time.[3] Unlike tone of voice, interpersonal distance, or gestures, times is the one nonverbal cue that cannot be filtered out of CMC. For example, a person can send a text message at a certain time of the day and when someone responds back to them they can gauge how much time elapsed between messages. Social Information Processing says that a prompt reply signals deference and liking in a new relationship or business context. A delayed response to someone may indicate receptivity and more liking in an intimate relationship; partners who are comfortable with each other do not need to reply as quickly.[4] So you would do well to send your text message at a time that fits the stage in the relationship and the tone that you want to convey. Others, such as Dr. Kevin B. Wright, examine the difference in developing and maintaining relationships both exclusively and primarily online.[11] Specifically, Wright has found the effectiveness of “openness and positivity” in online communication versus avoidance in offline relationships.[11]

Hyperpersonal model

According to the hyperpersonal model, it is possible to obtain more intimate relationships over CMC than face-to-face communication. Walther argues for this through four media effects that rely on distance between those communicating: selective self-presentation of the sender, over attribution of similarity of the receiver, an asynchronous channel and the self-fulfilling feedback prophecy:[3]

- Sender- Selective-Presentation: People who meet online have a better opportunity to make a favorable impression on the other. This is because the communicators can decide which information they would like to share about themselves, giving them the power to disclose only their good traits. Selective-Presentation is not as likely to occur in FtF communication due to the other’s ability to notice all the obvious traits in person.[3]

- Receiver- Over-attribution of Similarity: In the absence of FtF contextual cues, the likelihood of over-attributing given information of the sender is increased, often creating an idealized image of the message sender. This is also known as social-identity-deindividuation (or SIDE).[12] Described by Martin Lea and Russell Spears, SIDE develops when a CMC relationship develops over an "exaggerated sense of similarity and group solidarity" in the absence of "contrasting" cues.[3] This is especially true when parties meet through an online support group. These members seem to agree, encourage and offer advice to the other party which makes the user feel they have more in common. Over-attribution is also found in online dating. While reading a perspective date’s profile, the reader is likely to see themselves as similar to one another and therefore become more interested in them than they originally would have been.

- Channel- Communication on Your Own Time Asynchronous channel: As CMC is an asynchronous channel of communication, communication messages do not have to be sent simultaneously, allowing a sender to edit messages more than in face to face communication.[3] CMC users are free to write person-centered messages, knowing that the recipient will read the message at a convenient time. This is a big plus, especially when communicating across time zones or for people whose waking hours are out of sync.This also helps with multitasking and privacy. CMC users are able to communicate and perform other tasks at the same time. This is not as easy in FtF communication. As for privacy goes, taking part in CMC helps you limit the number of people that would hear the information as compared to FtF communication in a public setting.

- Feedback- Self-fulfilling prophecy: A self-fulfilling prophecy is the, "tendency for a person’s expectation of others to evoke a response from them that confirms what was anticipated." This process creates hyperpersonal relationships only if CMC parties first form highly favorable impressions of each other. An example of this is if you think that someone is a polite person, you will treat them with respect and they, in return, will be polite to you. Thus, fulfilling the expectations that you originally held for them.

Low warrant vs. high warrant

With the introduction of many social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn there are many opportunities for people to interact using CMC. There are many factors that set social media apart from the text-only CMC that Walther originally studied. Some of which being the inclusion of pictures, videos, and the ability to build your own profile and help shape someone else’s profile. This creates many contradictions. For example, let’s say you describe yourself as a quiet, reserved person but your friends add pictures of you out at the bar with a bunch of people. These two ideas contradict each other. How you process this contradiction is the main idea of Walther’s Warranting Theory.[3] According to Walther, “if the information we’re reading has warranting value, then it gives us reason to believe It is true”.[3]

There are two types of warranting information: low warrant and high warrant. Low warrant information is easily manipulated and therefore less believable. An example of this is information you yourself put on your profile such as interests and hobbies. High warrant information is more likely to be accepted as true. An example of this is information added to your profile by others because the owner cannot easily change it.

Walther has previously tested warranting values by assigning random participants to view fake Facebook pages. His experiments confirmed that people value high warrant information.[3] In one of his studies it was found that credibility levels and attractiveness were swayed by comments made on the profile by people other than its owner.[3] Another study also confirmed his beliefs by comparing high and low warrant information and finding that friends’ remarks were valued higher than the owner’s claims in regards to physical attractiveness and outgoingness. These studies have found that, unlike email, communication comes from both the owner and other users of social media and viewers do not give these two opinions equal value.[3]

Examples

- A blind date: Imagine two people are being sent on a blind date by their friends. The date is scheduled three weeks in advance, so the friends give the two people going on the blind date each other's email addresses so they can get to know each other a little before the date. One initiates and sends the other an email, and after a couple of days they slowly begin to disclose information. Each person has the ability to carefully craft their message to the other, and to edit how much information to disclose to one another. With these initial conversations occurring over the internet, many of the initial uncertainties they have about meeting each other may be dissipated. Over the three-week time period, the two people can grow close and be excited to meet each other, so when they do meet, the atmosphere will not be awkward but instead, the two people can feel like friends.

- Viral marketing: Or “creating a process where interested people can market to each other”, is used to influence the adoption and use of products and services.[13] Viral marketing occurs largely through CMC interpersonal influence, most commonly through online social networks.[13] Social information-processing theory views the social network as “an important source of information and cues for behavior and action for individuals”.[13] Compared to interpersonal communication through a face-to-face social network, the social information processing theory argues the CMC interpersonal communication of viral marketing achieves greater influence due to many factors, including: the ability to influence a large number of individuals (for example, through multiple email recipients), minimal effort to influence (in terms of reach and ease of information sharing), the ability for synchronous, as well as asynchronous communication and the ability to adopt influence strategies based on real-time feedback.[13]

Criticisms

Despite the fact that social information processing theory offers a more optimistic perspective through which to perceive of and analyze online interactions, the theory is not without its criticisms. Even though Walther[1] proposes that users of computer-mediated communication (CMC) have the same interpersonal needs met as those communicating face-to-face (FtF), he proposes that the lack of visual cues inherent in CMC are disadvantages to be overcome over time.[7] Thus, more time is needed for interactants to get to know one another - although he maintains that the same intimacy can be reached, just over a longer amount of time.[1]

Furthermore, many of Walther's initial hypotheses relied on the assumption that positive social behaviors would be greater in face-to-face interactions than those in CMC. In a 1995 study, Walther used this hypothesis but added that any initial differences in socialness between the two media would disappear in time.[14] Walther was surprised to find that his results turned out to be contrary to this prediction. The results showed that, regardless of time-scale, CMC groups were rated higher in most measures of relational communication than those participating in the FtF condition.[14]

Also, a study from Robert Tokunaga found that while social information processing theory holds true for people with high individualist values, the same could not be said for those with high collectivist values.[15]

New technologies

The label 'social media' has been attached to a quickly growing number of Web sites whose content is primarily user-driven.[16] These communities are large-scale examples of SIP. Navigating the 'social' world of information online is largely a product of interpersonal connections online, and has prompted the creation of aggregating, or collaborative sources, to help assist collective groups of people sort through information. Learning about others through the concept of "seamless sharing" opens another word for SIP. Some computer tools that facilitate this process are:

- Authoring tools: e.g., blogs

- Collaboration tools: e.g., Wikipedia

- Tagging systems (social bookmarkingsocial bookmarking): e.g., del.icio.us, Flickr, CiteULike

- Social networking: e.g., Facebook, MySpace, Twitter

- Collaborative filtering: e.g., Reddit, the Amazon Product Recommendation System, Yahoo answers, Urtak

- Social Information Aggregation: e.g., scratchmysoul.com

The process of learning from and connecting with others has not changed, but is instead manifested on the Internet. There are many different opinions regarding the value of social media interactions. These resources allow for people to connect and develop relationships using methods alternative to the traditional FtF-exclusive past, thus, making CMC more prevalent amongst social media users.

See also

- Hyperpersonal model

- Media naturalness theory

- Media richness theory

- Warranting theory

- Social identity model of deindividuation effects (SIDE)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Walther, Joseph B. (1992). "Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated interaction: A relational perspective.". Communication Research 19 (1): 52–90. doi:10.1177/009365092019001003.

- ↑ Olaniran, Bolanle A. "Social Information Processing Theory (SIPT): A Cultural Perspective for International Online Communication Environments." IGI Global (2011): 45-46. IGI Global, 2011. Web. 25 Nov. 2011.<http://www.igi-global.com/viewtitlesample.aspx?id=55560>.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 Griffin, Em. "Social Information Processing Theory of Joseph Walther". A First Look at Communication Theory 8th Ed. McGraw Hill. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 GRIFFIN, E. M. (2009). A first look at communication theory. (seventh ed., p. 486). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

- ↑ McQuail, Denis. (2005). Mcquail's Mass Communication Theory. 5th ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- ↑ Thurlow, C., Lengel, L. & Tomic, A. (2004). Computer mediated communication: Social interaction and the internet. London: Sage.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Walther, J. B., & Parks, M. (2002). Cues filtered out, cues filtered in. Handbook of interpersonal communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Walther, J. B. (1 March 2005). "Let Me Count the Ways: The Interchange of Verbal and Nonverbal Cues in Computer-Mediated and Face-to-Face Affinity". Journal of Language and Social Psychology 24 (1): 36–65. doi:10.1177/0261927X04273036.

- ↑ Farrer, James, and Jeff Gavin. "Online Dating in Japan: A Test of Social Information Processing Theory." CyberPsychology & Behavior 12.4 (2009): 407-08. EBSCO Host. Web. 25 Nov. 2011. <http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=51da6aa4-3bb8-4918-962f-379b986f4198%40sessionmgr14&vid=7&hid=14>.

- ↑ Jones, Susanne (March 2009). "Relational Messages". Encyclopedia of Human Relationships 3. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Wright, Kevin B. (June 2004). "ON-LINE RELATIONAL MAINTENANCE STRATEGIES AND PERCEPTIONS OF PARTNERS WITHIN EXCLUSIVELY INTERNET-BASED AND PRIMARILY INTERNET-BASED RELATIONSHIPS". Communication Studies 55 (2): 239–253. doi:10.1080/10510970409388617.

- ↑ POSTMES, T.; SPEARS, R.; LEA, M. (1 December 1998). "Breaching or Building Social Boundaries?: SIDE-Effects of Computer-Mediated Communication". Communication Research 25 (6): 689–715. doi:10.1177/009365098025006006.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Subramani, Mani R.; Rajagopalan, Balaji (1 December 2003). "Knowledge-sharing and influence in online social networks via viral marketing". Communications of the ACM 46 (12): 300. doi:10.1145/953460.953514.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Joinson, Adam. (2003). Understanding the psychology of Internet behavior. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ Tokunaga, Robert (2009). "High-Speed Internet Access to the Other: The Influence of Cultural Orientations on Self-Disclosures in Offline and Online Relationships". Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 38 (3).

- ↑ Lerman, Kristina. "Social Information Processing". Google. Retrieved November 2011.

Further reading

- AAAI, Social Information Processing Symposium, Stanford, AAAI, March 2008.

- Camerer, Colin F., and Ernst Fehr, "When Does ‘‘Economic Man’’ Dominate Social Behavior?"

- Chi, Ed H., " Augmenting Social Cognition: From Social Foraging to Social Sensemaking," (video) (at Google), February 2007. (pdf), AAAI Symposium, March 2008, (video) (at PARC), May 2008.

- Crane, Riley (2008), Viral, Quality, and Junk Videos on YouTube, AAAI Seminar, March 2008

- Denning, Peter J. (2006), "Hastily Formed Networks", Communication of the ACM 49 (4)

- Denning, Peter J., "Infoglut," ACM, July. 2006.

- Denning, Peter J. and Rick Hayes-Roth, "Decision Making in Very Large Networks," ACM, Nov. 2006.

- Fu, Wai-Tat (April 2008), "The Microstructures of Social Tagging: A Rational Model", Proceedings of the ACM 2008 conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work.: 229–238, doi:10.1145/1460563.1460600

- Fu, Wai-Tat (August 2009), "A Semantic Imitation Model of Social Tagging.", Proceedings of the IEEE conference on Social Computing: 66–72

- Hogg, Tad, and Bernardo A. Huberman, "Solving the organizational free riding problem with social networks"

- Huang, Yi-Ching (Janet), "You are what you tag," (ppt) AAAI Seminar, March 2008.

- Huberman, Bernardo, "Social Dynamics in the Age of the Web," (video) (PARC) January 10, 2008.

- Judson, Olivia, "Feel the Eyes Upon You," The New York Times, August 3, 2008,

- Lerman, Kristina, "Social Information Processing in News Aggregation," IEEE Internet Computing, November–December 2007.

- Nielsen, Michael, The Future of Science. A book in preparation.

- Nielsen, Michael, Kasparov versus the World. A blog post about a 1999 chess game in which Garry Kasparov (eventually) won a game against a collective opponent.

- Page, Scott E., The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies, Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Segaran, Toby, Programming Collective Intelligence: Building Smart Web 2.0 Applications, O'Reilly, 2007.

- Shalizi, Cosma Rohilla, "Social Media as Windows on the Social Life of the Mind"

- Smith, M., Purser, N. and Giraud-Carrier, C. (2008). Social Capital in the Blogosphere: A Case Study. In Papers from the AAAI Spring Symposium on Social Information Processing, K. Lerman et al. (Eds.), Technical Report SS-08-06, AAAI Press, 93-97.

- Spinellis, Diomidis, Wikipedia Faces no Limits to Growth(ACM article, subscription required).

- Stoyanovich, Julia, "Leveraging Tagging to Model User Interests in del.icio.us," (ppt) AAAI Seminar, March 2008.

- Whittaker, Steve, "Temporal Tagging," AAAI Symposium, March 2008.