Social democracy

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

|

Development |

Social democracy is a political ideology that officially has as its goal the establishment of democratic socialism through reformist and gradualist methods.[1] Alternatively, social democracy is defined as a policy regime involving a universal welfare state and collective bargaining schemes within the framework of a capitalist economy. It is often used in this manner to refer to the social models and economic policies prominent in Western and Northern Europe during the latter half of the 20th century.[2][3]

Following the split between reformists and revolutionary socialists in the Second International, social democrats have advocated for a peaceful and evolutionary transition of the economy to socialism through progressive social reform of capitalism.[4][5] Social democracy asserts that the only acceptable constitutional form of government is representative democracy under the rule of law.[6] It promotes extending democratic decision-making beyond political democracy to include economic democracy to guarantee employees and other economic stakeholders sufficient rights of co-determination.[6] It supports a mixed economy that opposes the excesses of capitalism such as inequality, poverty, and oppression of various groups, while rejecting both a totally free market or a fully planned economy.[7] Common social democratic policies include advocacy of universal social rights to attain universally accessible public services such as education, health care, workers' compensation, and other services, including child care and care for the elderly.[8] Social democracy is connected with the trade union labour movement and supports collective bargaining rights for workers.[9] Most social democratic parties are affiliated with the Socialist International.[1]

Social democracy originated in 19th century Germany from the influence of both the reformist socialism of Ferdinand Lassalle, as well as the internationalist revolutionary socialism advanced by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.[10] The Marxists and Lassallians were in rivalry over political influence in the movement until 1868–1869 when Marxism became the official basis of Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany.[11] In the Hague Congress of 1872, Marx modified his stance on revolution by declaring that there were countries with democratic institutions where reformist measures could be advanced, saying that "workers may achieve their aims by peaceful means, But this is not true of all countries."[12] Marx stressed his support for the Paris Commune due to its representative democracy based on universal suffrage.[12]

Fabians and Marxists influenced by Eduard Bernstein advocate an evolutionary approach to the advancement of socialism. Bernstein opposed classical and orthodox Marxisms' assumption of the necessity of socialist revolution and class conflict, claiming that socialism could be achieved via representative democracy and cooperation between people regardless of class.[13] Social democracy in the early 20th century began to transition away from association with Marxism towards liberal socialism, particularly through the influence of figures like Carlo Rosselli who sought to disassociate socialism from the legacy of Marxism.[14] By the post-World War II period, most social democrats in Europe had abandoned their ideological connection to Marxism and shifted their emphasis toward social policy reform in place of transition from capitalism to socialism.[15] The Third Way is a major faction in social democratic parties that developed in the 1990s, which has claimed to be social democratic though others have identified it as being effectively a neoliberal movement.[16]

Development of social democracy

First International era, 1863–1889

The origins of social democracy have been traced to the 1860s, with the rise of the first major working-class party in Europe, the General German Workers' Association (ADAV) founded by Ferdinand Lassalle.[17] At the same time the International Workingmen's Association also known as the First International was founded in 1864 brought together socialists of various stances, and initially brought forth a conflict between Karl Marx and the anarchists led by Mikhail Bakunin over the role of the state in socialism, with Bakunin rejecting any role for the state.[12] Another issue at the First International was the role of reformism.[18]

Although Lassalle was not a Marxist, he was influenced by the theories of Marx and Engels, and he accepted the existence and importance of class struggle. However unlike Marx's and Engels' The Communist Manifesto, Lassalle promoted class struggle in a more moderate form.[19] While Marx viewed the state negatively as an instrument of class rule that should only exist temporarily upon the rise to power of the proletariat and then dismantled, Lassalle accepted the state. Lassalle viewed the state as a means through which workers could enhance their interests and even transform the society to create an economy based on worker-run cooperatives. Lassalle's strategy was primarily electoral and reformist, with Lassalleans contending that the working class needed a political party that fought above all for universal adult male suffrage.[17]

The ADAV's party newspaper was called Der Sozialdemokrat ("The Social Democrat"). Marx and Engels responded to the title "Sozialdemocrat" with distaste, Engels once wrote "But what a title: Sozialdemokrat!...Why don't they simply call it The Proletarian." Marx agreed with Engels that "Sozialdemokrat" was a bad title.[19] However the origins of the name "Sozialdemokrat" actually traced back to Marx's German translation in 1848 of the French political party known as "Partie Democrat-Socialist" into "Partei der Sozialdemokratie"; but Marx did not like this French party because he viewed it as dominated by the middle class, and associated the word "Sozialdemokrat" with that party.[20] There was a Marxist faction within the ADAV represented by Wilhelm Liebknecht who became one of the editors of the Die Sozialdemokrat.[19]

Faced with opposition from liberal capitalists to his socialist policies, Lassalle controversially attempted to forge a tactical alliance with the conservative aristocratic Junkers due to their anti-bourgeois attitudes, as well as with Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.[17] Friction in the ADAV arose over Lassalle's policy of a friendly approach to Bismarck that had assumed that Bismarck in turn would be friendly towards them that did not succeed. This approach opposed by the party's Marxists, including Liebknecht.[20] Opposition in the ADAV to Lassalle's friendly approach to Bismarck's government resulted in Liebknecht resigning from his position as editor of Die Sozialdemokrat, and left the ADAV in 1865. In 1869 Liebknecht along with Marxist August Bebel founded the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP), that was founded as a merger of three groups: petit-bourgeois Saxon People's Party (SVP), a faction of the ADAV, and members of the League of German Workers Associations (VDA).[20]

Though the SDAP was not officially Marxist, it was the first major working-class organization to be led by Marxists and Marx and Engels had direct association with the party. The party adopted stances similar to those adopted by Marx at the First International. There was intense rivalry and antagonism between the SDAP and the ADAV, with the SDAP being highly hostile to the Prussian government while the ADAV pursued a reformist and more cooperative approach.[21] This rivalry reached its height involving the two parties' stances on the Franco-Prussian War, with the SDAP refusing to support Prussia's war effort by claiming it rejected it as an imperialist war by Bismarck, while the ADAV supported the war.[21]

In the aftermath of the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, revolution broke out in France, with revolutionary army members along with working-class revolutionaries founding the Paris Commune.[22] The Paris Commune appealed both to the citizens of Paris regardless of class, as well as to the working class who were a major base of support for the government by appealing to them via militant rhetoric. In spite of such militant rhetoric to appeal to the working class, the Commune also received substantial support from the middle-class bourgeoisie of Paris, including shopkeepers and merchants. The Commune, in part due to its sizable number neo-Proudhonians and neo-Jacobins in the Central Committee, declared that the Commune was not opposed to private property, but rather hoped to create the widest distribution of it.[23] The political composition of the Commune included twenty-five neo-Jacobins, fifteen to twenty neo-Proudhonians and protosyndicalists, nine or ten Blanquists, a variety of radical republicans, and a few Internationalists influenced by Marx.[24]

In the aftermath of the collapse of the Paris Commune in 1871, Marx praised the Paris Commune in his work The Civil War in France (1871) for its achievements, in spite of its pro-bourgeois influences, and called it an excellent model of the dictatorship of the proletariat in practice, as it had dismantled the apparatus of the bourgeois state, including its huge bureaucracy; military; and its executive, judicial, and legislative institutions; with a working-class state with broad popular support.[25] However the collapse of the Commune and the persecution of its anarchist supporters had the effect of weakening the influence of the Bakuninist anarchists in the First International, this would result in Marx expelling the weakened rival Bakuninists from the International a year later.[25]

In Britain, the achievement of legalization of trade unions under the Trade Union Act of 1871 drew British trade unionists to believe that working conditions could be improved through parliamentary means.[26]

At the Hague Congress of 1872, Marx altered his position on the necessity of a violent revolution to achieve socialism, by taking into account the different institutions of different countries.[12] At the Congress, Marx declared:

We know that the institutions, customs and traditions in the different countries must be taken into account; and we do not deny the existence of countries like America, England, and...I might add Holland, where the workers may achieve their aims by peaceful means. But this is not true of all countries.

Marx was not optimistic that Germany at the time was not open to a peaceful means to achieve socialism, especially after German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had enacted Anti-Socialist Laws in 1878.[27] At the time of the Anti-Socialist Laws beginning to be drafted, but not yet published, in 1878, Marx spoke of the possibilities of legislative reforms by an elected government composed of working-class legislative members, but also of the willingness to use force should force be used against the working class:

If in England, for instance, or the United States, the working class were to gain a majority in Parliament or Congress, they could, by lawful means, rid themselves of such laws and institutions as impeded their development, though they could only do insofar as society had reached a sufficiently mature development. However, the "peaceful" movement might be transformed into a "forcible" one by resistance on the part of those interested in restoring the former state of affairs; if (as in the American Civil War and French Revolution) they are put down by force, it is as rebels against "lawful" force.—Karl Marx, 1878.[27]

Engels in his study England in 1845 and in 1885 (1885) wrote a study that analysed the changes in the British class system from 1845 to 1885, in which he commended the Chartist movement for being responsible for the achievement of major breakthroughs for the working class.[28] Engels stated that during this time Britain's industrial bourgeoisie had learned "that the middle class can never obtain full social and political power over the nation except by the help of the working class".[27] In addition he noticed "a gradual change over the relations between the two classes".[28] This change he described was manifested in the change of laws in Britain, that granted political changes in favour of the working class that the Chartist movement had demanded for years:

The 'Abolition of the Property Qualification' and 'Vote by Ballot' are now the law of the land. The Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884 make a near approach to 'universal suffrage', at least such as it now exists in Germany.—Friedrich Engels, England in 1845 and in 1885 (1885).[28]

A major non-Marxian influence on social democracy came from the British Fabian Society founded in 1884 by Frank Podmore that emphasized the need for a gradualist evolutionary and reformist approach to the achievement of socialism.[29] The Fabian Society was founded as a splinter group from the Fellowship of the New Life due to opposition within that group to socialism.[30] Unlike Marxism, Fabianism did not promote itself as a working-class-led movement, and it largely had middle-class members.[31] The Fabian Society published the Fabian Essays on Socialism (1889) that was substantially written by George Bernard Shaw.[32] Shaw referred to Fabians as

"all Social Democrats, with a common confiction of the necessity of vesting the organization of industry and the material of production in a State identified with the whole people by complete Democracy."—George Bernard Shaw[32]

Other important early Fabians, included Sidney Webb, who from 1887 to 1891 wrote the bulk of the Society's official policies.[33] Fabianism would become a major influence on the British labour movement.[31]

Second International era, "reform or revolution" dispute, 1889–1914

The modern social democratic movement came into being through a division within the socialist movement, this division can be described as a parting of ways between those who insisted upon political revolution as a precondition for the achievement of socialist goals and those who maintained that a gradual or evolutionary path to socialism was both possible and desirable.[34]

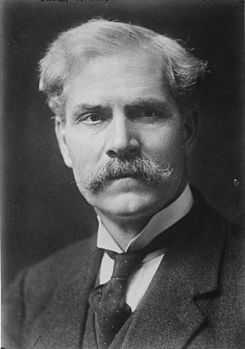

The influence of the Fabian Society in Britain grew in the British socialist movement in the 1890s, especially within the Independent Labour Party (ILP) founded in 1893.[35] Important ILP members were affiliated with the Fabian Society, including Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald - the future British Prime Minister.[35] Fabian influence in British government affairs also emerged, such as Fabian member Sidney Webb being chosen to take part in writing what became the Minority Report of the Royal Commission on Labour.[36] While Hardie was nominally a member of the Fabian Society, as leader of the ILP held close relations with certain Fabians, such as Shaw, while he was antagonistic to others such as the Webbs.[37] As ILP leader, Hardie rejected revolutionary politics while declaring that he believed the party's tactics should be "as constitutional as the Fabians".[37]

Another important Fabian figure who joined the ILP was Robert Blatchford who wrote the work Merrie England (1894) that endorsed municipal socialism.[38] Merrie England was a major publication that sold 750,000 copies within one year.[39] In Merrie England Blatchford distinguished two types of socialism: an "ideal socialism" and a "practical socialism".[40] Blatchford's practical socialism was a state socialism that identified existing state enterprise such as the Post Office run by the municipalities as a demonstration of practical socialism in action, he claimed that practical socialism should involve the extension of state enterprise to the means of production as common property of the people.[40] While endorsing state socialism, Blatchford's Merrie England and his other writings were influenced by anarchist communist William Morris, as Blatchford himself attested to, and Morris' anarchist communist themes are present in Merrie England.[40]

Shaw published the Report on Fabian Policy (1896) that declared: "The Fabian Society does not suggest that the State should monopolize industry as against private enterprise or individual initiative."[41]

Major developments in social democracy as a whole emerged with the ascendance of Eduard Bernstein as a proponent of reformist socialism and an adherent of Marxism.[42] Bernstein had resided in Britain in the 1880s at the time when Fabianism was arising, and is believed to have been strongly influenced by Fabianism.[43] However he publicly denied having strong Fabian influences on his thought.[44] Bernstein did acknowledge that he was influenced by Kantian epistemological skepticism while he rejected Hegelianism. He and his supporters urged the Social Democratic Party of Germany to merge Kantian ethics with Marxian political economy.[44] On the role of Kantian criticism within socialism, Bernstein said:

The method of this great philosopher [Kant] can serve as a pointer to the satisfying solution to our problem. Of course we don’t have to slavishly adhere to Kant’s form, but we must match his method to the nature of our own subject [socialism], displaying the same critical spirit. Our critique must be direct against both a scepticism that undermines all theoretical thought, and a dogmatism that relies on ready-made formulas.—Eduard Bernstein[44]

The term "revisionist" was applied to Bernstein by his critics who referred to themselves as "orthodox" Marxists, even though Bernstein claimed that his principles were consistent with Karl Marx's and Friedrich Engels' stances, especially in their later years when Marx and Engels advocated that socialism should be achieved through parliamentary democratic means wherever possible.[42] Bernstein and his faction of revisionists criticized orthodox Marxism and particularly its founder Karl Kautsky, for having disregarded Marx's view of the necessity of evolution of capitalism to achieve socialism by replacing it with an "either/or" polarization between capitalism and socialism; claiming that Kautsky disregarded Marx's emphasis on the role of parliamentary democracy in achieving socialism; as well as criticizing Kautsky for his idealism of state socialism.[45] However Kautsky did not deny a role for democracy in the achievement of socialism, as he claimed that Marx's dictatorship of the proletariat was not a form of government that rejected democracy as critics had claimed it was, but a state of affairs that Marx expected would arise should the proletariat gain power and be faced with fighting a violent reactionary opposition.[12]

Bernstein had held close association to Marx and Engels, but he saw flaws in Marxian thinking and began such criticism when he investigated and challenged the Marxian materialist theory of history.[46] He rejected significant parts of Marxian theory that were based upon Hegelian metaphysics, he rejected the Hegelian dialectical perspective.[47] Bernstein distinguished between early Marxism as being its immature form: as exemplified by The Communist Manifesto written by Marx and Engels in their youth, that he opposed for what he regarded as its violent Blanquist tendencies; and later Marxism as being its mature form that he supported.[48]

Bernstein declared that the massive and homogeneous working class claimed in the Communist Manifesto did not exist, and that contrary to claims of a proletarian majority emerging, the middle class was growing under capitalism and not disappearing as Marx had claimed. Bernstein noted that the working class was not homogeneous but heterogeneous, with divisions and factions within it, including socialist and non-socialist trade unions. Marx himself later in his life acknowledged that the middle class was not disappearing, in his work Theories of Surplus Value. However due to the popularity of the Communist Manifesto and the obscurity of Theories of Surplus Value, Marx's acknowledgement of this error is not well known.[49]

Bernstein criticized Marxism's concept of "irreconciliable class conflicts" and Marxism's hostility to liberalism.[50] He challenged Marx's position on liberalism by claiming that liberal democrats and social democrats held common grounds that he claimed could be utilized to create a "socialist republic".[50] He believed that economic class disparities between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat would gradually be eliminated through legal reforms and economic redistribution programs.[50] Bernstein rejected the Marxian principle of dictatorship of the proletariat, claiming that gradualist democratic reforms will improve the rights of the working class.[51] According to Bernstein, unlike orthodox Marxism, social democracy did not seek to create a socialism separate from bourgeois society but instead sought to create a common development based on Western humanism.[52] The development of socialism under social democracy does not seek to rupture existing society and its cultural traditions but to act as an enterprise of extension and growth.[53] Furthermore, he believed that class cooperation was a preferable course to achieve socialism, rather than class conflict.[54] On the issue of class conflict and responding to the Marxian principle of dictatorship of the proletariat, Bernstein said:

"No one thinks of destroying civil society as a community ordered in a civilized war. Quite to the contrary, Social Democracy does not want to break up civil society and make all its members proletarians together; rather, it ceaselessly labours to raise the worker from the social position of a proletarian to that of a citizen and thus make citizenship universal. It does not want to replace civil society with a proletarian society but a capitalist order of society with a socialist one." Eduard Bernstein[55]

Bernstein urged social democrats to be committed to a long-term agenda of transforming the capitalist economy to a socialist economy rather than a sudden upheaval of capitalism, saying:

"Social democracy should neither expect nor desire the imminent collapse of the existing economic system … What social democracy should be doing, and doing for a long time to come, is organize the working class politically, train it for democracy, and fight for any and all reforms in the state which are designed to raise the working class and make the state more democratic." Eduard Bernstein[56]

Bernstein accepted a mixed economy for an unspecified amount of time:[57]

"It [socialism] would be completely mad to burden itself with the additional tasks of so complex a nature as the setting up and controlling of comprehensive state production centers on a mass scale – quite apart from the fact that only certain specific branches of production can be run on a national basis…Competition would have to be reckoned with, at least in the transitional period." Eduard Bernstein.[57]

"[...] in addition to public enterprises and cooperative enterprises, there are enterprises run by private individuals for their own gain. In time, they will of their own accord acquire a cooperative character." Eduard Bernstein.[58]

Bernstein responded to critics that he was not destroying Marxism, but claimed that he was "modernizing Marxism" that was required "to separate the vital parts of [Marx's] theory from its outdated accessories". He asserted his support for the Marxian conception of a "scientifically based" socialist movement, and said that such a movement's goals must be determined in accordance with "knowledge capable of objective proof, that is, knowledge which refers to, and conforms with, nothing but empirical knowledge and logic". As such, Bernstein was strongly opposed to dogmatism within the Marxist movement.[59]

Rosa Luxemburg representing revolutionary socialism, staunchly condemned Bernstein's revisionism and reformism for being based on "opportunism in social democracy". She likened Bernstein's policies to that of the dispute between Marxists and the opportunistic Praktiker (Pragmatists). She denounced Bernstein's evolutionary socialism for being a "petty-bourgeois vulgarization of Marxism". She claimed that Bernstein's years of exile in Britain had made him lose familiarity with the situation in Germany where he was promoting evolutionary socialism.[60] Luxemburg sought to maintain social democracy as a revolutionary Marxist creed, saying:

"[T]here could be no socialism—at least in Germany—outside of Marxist socialism, and there could be no socialist class struggle outside of social democracy. From then on [the emergence of Marx’s theory], socialism and Marxism, the proletarian struggle for emancipation, and social democracy were identical."—Rosa Luxemburg, Reform or Revolution, p. 60.[59]

Both Kautsky and Luxemburg condemned Bernstein for his "flawed" philosophy of science for having abandoned Hegelian dialectics for Kantian philosophical dualism. Russian Marxist George Plekhanov joined Kautsky and Luxemburg in condemning Bernstein for having a neo-Kantian philosophy.[59] Kautsky and Luxemburg contended that Bernstein's empiricist viewpoints depersonalized and dehistoricized the social observer and reducing objects down to "facts". Luxemburg associated Bernstein with "ethical socialists" who she identified as being associated with the bourgeoisie and Kantian liberalism.[61]

In his introduction to the 1895 Marx's Class Struggles in France, Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist reformists and revolutionaries in the Marxist movement, by declaring that he was in favour of short-term tactics of electoral politics that included gradualist and evolutionary socialist measures while maintaining his belief that revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat should remain a goal. In spite of this attempt by Engels to merge gradualism and revolution, his effort only diluted the distinction of gradualism and revolution and had the effect of strengthening the position Praktikers.[62] Engels' statements in the French newspaper Le Figaro increased the public perception that Engels was becoming in favour of evolutionary socialism, in which he stated that "revolution" and the "so-called socialist society" was not a fixed concept, but was a constantly changing social phenomenon and said that this made "us [socialists] all evolutionists".[63] Engels also said that it would be "suicidal" to talk about a revolutionary seizure of power at a time when the historical circumstances favoured a parliamentarian road to power, that he predicted could bring "social democracy into power as early as 1898".[63] Engels stance of openly accepting gradualist, evolutionary, and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the historical circumstances did not favour revolution, caused confusion.[63] Bernstein interpreted this as indicating that Engels was moving towards accepting parliamentary reformist and gradualist stances, however Bernstein ignored that Engels' stances were tactical as a response to the particular circumstances, and that Engels was still committed to revolutionary socialism.[63]

In 1897 after Bernstein made a lecture in Britain to the Fabian Society titled "On What Marx Really Taught", Bernstein wrote a letter to orthodox Marxist Bebel in which he revealed to Bebel that he felt conflicted with what he had said at the lecture as well as revealing his intentions regarding revision of Marxism:

as I was reading the lecture, the thought shot through my head that I was doing Marx an injustice, that it was not Marx I was presenting...I told myself secretly that this could not go on. It is idle to reconcile the irreconcilable. The vital thing is to be clear as to where Marx is still right and where he is not.—Eduard Bernstein, 1897.[64]

What Bernstein was meaning was that that he believed that Marx was wrong in assuming that the capitalist economy would collapse as a result of its internal contradictions, as by the mid-1890s there was little evidence of such internal contradictions causing this to capitalism.[64]

The dispute over policies in favour of reform or revolution dominated discussions at the 1899 Hannover Party Conference of the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (SAPD). This issue had become especially prominent with the Millerand Affair in France in which Alexandre Millerand of the French Independent Socialist Party joined the non-socialist government of France's liberal Prime Minister Waldeck-Rousseau without seeking support from his party's leadership.[60] Millerand's actions provoked outrage amongst revolutionary socialists within the Second International, including the anarchist left and Jules Guesde's revolutionary Marxists.[60] In response to these disputes over reform or revolution, the 1900 Paris Congress of the Second International declared a resolution to the dispute, in which Guesde's demands were partially accepted in a resolution drafted by Kautsky that declared that overall socialists should not take part in a non-socialist government, but provided exceptions to this rule where necessary to provide the "protection of the achievements of the working class".[60]

Another prominent figure who influenced social democracy, was French revisionist Marxist and reformist socialist Jean Jaurès. During the 1904 Congress of the Second International, Jaurès challenged orthodox Marxist August Bebel, the mentor of Kautsky, over his promotion of monolithic socialist tactics. Jaurès claimed that no coherent socialist platform could be equally applicable to different countries and regions due to different political systems in them; noting that Bebel's homeland of Germany at the time was very authoritarian and had limited parliamentary democracy. He compared the limited political influence of socialism in government in Germany to the substantial influence that socialism had gained in France due to its stronger parliamentary democracy. He claimed that the example of the political differences between Germany and France demonstrated that monolithic socialist tactics were impossible, given the political differences of various countries.[65]

World Wars, revolutions and counterrevolutions, Great Depression 1914–1945

As tensions between Europe's Great Powers escalated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Bernstein feared that Germany's arms race with other powers was threatening the possibility of a major war.[66] Bernstein's fears were realized with the outbreak of World War I.[66]

Immediately after the outbreak of World War I, Bernstein traveled from Germany to Britain to meet with British Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald. Bernstein regarded the outbreak of the war with great dismay, but even though the two countries were at war with one another, MacDonald honoured Bernstein at the meeting.[67] In spite of Bernstein's and other social democrats' attempts to secure the unity of the Second International, with national tensions increasing between the countries at war, the Second International collapsed in 1914.[66] Anti-war members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) refused to support finances being given to the German government to support the war.[66] However a nationalist-revisionist faction of SPD members led by Friedrich Ebert, Gustav Noske, and Philipp Scheidemann, supported the war, arguing that Germany had the "right to its territorial defense" from the "destruction of Tsarist despotism".[68] The SPD's decision to support the war, including Bernstein's decision to support it, was heavily influenced by the fact that the German government lied to the German people, as it claimed that the only reason Germany had declared war on Russia was because Russia was preparing to invade East Prussia, when in fact this was not the case.[68] Jaurès opposed France's intervention in the war and took a pacifist stance, but was soon assassinated in 1914.[68]

Bernstein soon resented the war and by October 1914 was convinced of the German government's war guilt; and contacted the orthodox Marxists of the SPD, to unite to push the SPD to take an anti-war stance.[68] Kautsky attempted to put aside his differences with Bernstein and join forces in opposing the war, and Kautsky praised him for becoming a firm anti-war proponent, saying that although Bernstein had previously supported "civic" and "liberal" forms of nationalism, his committed anti-war position made him the "standard-bearer of the internationalist idea of social democracy".[68] The nationalist position by the SPD leadership under Ebert refused to rescind.[68]

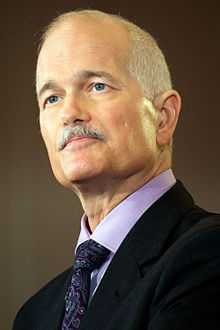

In Britain, the British Labour Party became divided on the war. Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald was one of a handful of British MPs who had denounced Britain's declaration of war on Germany. MacDonald was denounced by the pro-war press on accusations that he was "pro-German" and a pacifist, both charges that he denied.[69] In response to pro-war sentiments in the Labour Party, MacDonald resigned from being its leader and associated himself with the Independent Labour Party. Arthur Henderson became the new leader of the Labour Party, and served as a cabinet minister in Prime Minister Asquith's war government. After the February Revolution of 1917 in Russia (not to be confused with the October Revolution) in which the Tsarist regime in Russia was overthrown by the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, a democratic socialist movement led by Alexander Kerensky, MacDonald visited the Russian Provisional Government in June 1917, seeking to persuade Russia to oppose the war and seek peace. His efforts to unite the Russian Provisional Government against the war failed after Russia fell back into political violence resulting in the October Revolution in which the Bolsheviks led Vladimir Lenin's rise to power.[70] Though MacDonald critically responded to the Bolsheviks' political violence and rise to power by warning of "the danger of anarchy in Russia", he gave political support to the Bolshevik regime until the end of the war because he then thought that a democratic internationalism could be revived.[71] The British Labour Party's trade union affiliated membership soared during World War I. Henderson with the assistance of Sidney Webb designed a new constitution for the British Labour Party, in which it adopted a strongly left-wing platform in 1918 to ensure that it would not lose support to the new Communist Party, exemplified by Clause IV of the new constitution of the Labour Party.[72]

The overthrow of the Tsarist regime in Russia by Kerensky's Socialist-Revolutionaries in February 1917 impacted politics in Germany, as it ended the legitimation used by Ebert and other pro-war SPD members that Germany was in the war against a reactionary Russian government. With the overthrow of the Tsar and revolutionary socialist agitation increased in Russia, such events influenced socialists in Germany. With rising bread shortages in Germany amid war rationing, mass strikes occurred beginning in April 1917 with 300,000 strikers taking part in a strike in Berlin. The strikers demanded bread, freedom, peace, and the formation of workers' councils as was being done in Russia. Amidst the German public's uproar, the SPD alongside the Progressives and the Catholic labour movement in the Reichstag put forward the "Peace Resolution" on 19 July 1917 that called for a compromise peace to end the war, that was passed by a majority of members of the Reichstag. The German High Command opposed the Peace Resolution, however it did seek to end the war with Russia, and presented the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk to the Bolshevik regime in 1918 that agreed to the terms and the Reichstag passed the treaty, that included the support of the SPD, the Progressives, and the Catholic political movement.[73]

By late 1918 the war situation for Germany had become hopeless, and Kaiser Wilhelm II was pressured to make peace. Wilhelm II appointed a new cabinet that included SPD members in it. At the same time the Imperial Naval Command was determined to make a heroic last stand against the British Royal Navy, and on 24 October 1918 it issued orders for the German Navy to depart to confront while the sailors refused, resulting in the Kiel Mutiny. The Kiel Mutiny resulted in the German Revolution of 1918–1919. Faced with military failure and revolution the Chancellor, Prince Maximilian of Baden resigned, giving SPD leader Ebert the position of Chancellor, Wihelm II abdicated the German throne immediately afterwards, and the German High Command officials Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff resigned whilst refusing to end the war to save face, leaving the Ebert government and the SPD-majority Reichstag to be forced to make the inevitable peace with the Allies and take the blame for having lost the war. With the abdication of Wilhelm II, Ebert declared Germany to be a republic and signed the armistice that ended World War I on 11 November 1918.

The new social democratic government in Germany faced political violence in Berlin by a movement of communist revolutionaries known as the Spartacist League who sought to repeat the feat of Lenin and the Bolsheviks in Russia, by overthrowing the German government.[74] Tensions between the governing "Majority" Social Democrats (led by Ebert) versus the strongly left-wing elements of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) and communists over Ebert's refusal to immediately reform the German Army, resulted in the "January rising" by the newly formed Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the USPD, resulting in communists mobilizing a large workers' demonstration. The SPD responded by holding a counterdemonstration that was effective in demonstrating support for the government, and the USPD soon withdrew its support for the rising.[75] However the communists continued to revolt, and between 12 to 28 January 1919, communist forces had seized control of several government buildings in Berlin. Ebert responded by requesting that Defense Minister Gustav Noske take charge of loyal soldiers to fight the communists and secure the government.[74] Ebert was furious with the communists' intransigence and said that he wished "to teach the radicals a lesson they would never forget". Noske was able to rally groups of mostly reactionary ex-soldiers, known as the Freikorps who were eager to fight the communists. The situation soon went completely out of control when the recruited Freikorps went on a violent rampage against workers and murdered the communist leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg. The atrocities by the government-recruited Freikorps against the communist revolutionaries badly tarnished the reputation of the SPD and strengthened the confidence of reactionary forces. In spite of this, the SPD was able to win the largest number of seats in the parliamentary election held on 19 January 1919 and Ebert was elected President of Germany, but the USPD in response to the atrocities committed by the government-recruited Freikorps, refused to support the SPD government.[75]

Due to the unrest in Berlin, the construction of the constitution of the new German republic was created in the city of Weimar, and is referred to as the Weimar Republic. Upon founding the new government, President Ebert cooperated with liberal members of his coalition government to create the constitution, Ebert sought to begin a program of nationalizations of some parts of the economy. Political unrest and violence continued and the government's continued reliance on the help of the Freikorps counterrevolutionaries to fight the communist revolutionaries continued to alienate potential left-wing support for the SPD. The SPD coalition government's acceptance of the harsh peace conditions of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, infuriated the right, including the Freikorps that had previously been willing to cooperate with the government to fight the communists. In the German parliamentary election of June 1919, the SPD share of the vote declined significantly. In March 1920, a group of right-wing militarists led by Wolfgang Kapp and former German military chief-of-staff Erich Ludendorff initiated a briefly successful putsch against the German government, in what became known as the Kapp Putsch, however the putsch failed and the government was restored.[76]

At a global level, after World War I several attempts were made to re-found the Second International that collapsed amidst national divisions in the war. The Vienna International formed in 1921 attempted to end the rift between reformist socialists - including social democrats; and revolutionary socialists - including communists, and particularly Mensheviks.[77] However a crisis soon erupted that involved the new country of Georgia led by a social democratic government led by President Noe Zhordania, that had declared itself independent from Russia in 1918 whose government had been endorsed by multiple social democratic parties. At founding meeting of the Vienna International, the discussions were interrupted by the arrival of a telegram from President Zhordania who said that Georgia was under invasion by Bolshevik Russia. Delegates attending the International's founding meeting were stunned, particularly the Bolshevik representative from Russia, Mecheslav Bronsky, who refused to believe this and left the meeting to seek confirmation of this, but upon confirmation Bronsky did not return to the meeting.[78] The overall response from the Vienna International was divided, the Mensheviks demanded that the International immediately condemn Russia's aggression against Georgia, but the majority as represented by German delegate Alfred Henke sought to exercise caution and said that the delegates should wait for confirmation.[77] Russia's invasion of Georgia completely violated the non-aggression treaty signed between Lenin and Zhordania, as well as violating Georgia's sovereignty by annexing Georgia directly into the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. Tensions between Bolsheviks and social democrats worsened with the Kronstadt rebellion.[78] Unrest by leftists against the Bolshevik government in Russia resulted in the Kronstadt rebellion, Russian social democrats distributed leaflets calling for a general strike against the Bolshevik regime, the Bolsheviks responded by forcefully repressing the rebels.[79]

Relations between the social democratic movement and Bolshevik Russia descended into complete antagonism in response to the Russian famine of 1921 and the Bolsheviks' violent repression of opposition to their government. Multiple social democratic parties were disgusted with Russia's Bolshevik regime, particularly Germany's SPD and the Netherlands' Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) that denounced the Bolsheviks for defiling socialism and declared that the Bolsheviks had "driven out the best of our comrades, thrown them into prison and put them to death".[80]

In May 1923, social democrats united to found their own international, the Labour and Socialist International (LSI), founded in Hamburg, Germany. The LSI declared that all its affiliated political parties would retain autonomy to make their own decisions regarding internal affairs of their countries; but that international affairs would be addressed by the LSI.[77] The LSI addressed the issue of the rise of fascism, by declaring the LSI to be anti-fascist.[81] In response to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 between the democratically elected Republican government versus the authoritarian right-wing Nationalists led by Francisco Franco with the support of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, the Executive Committee of the LSI declared not only its support for the Spanish Republic but also that it supported the Spanish government having the right to purchase arms to fight Franco's Nationalist forces. LSI-affiliated parties, including the British Labour Party declared their support for the Spanish Republic.[82] However the LSI was criticized on the left for failing to put action into its anti-fascist rhetoric.[81]

The stock market crash of 1929 that began an economic crisis in the United States that globally spread and became the Great Depression profoundly affected economic policymaking.[83] The collapse of the gold standard and the emergence of mass unemployment resulted in multiple governments recognizing the need for state macroeconomic intervention to reduce unemployment as well as economic intervention to stabilize prices, a proto-Keynesianism that John Maynard Keynes himself would soon publicly endorse.[84] Multiple social democratic parties declared the need for substantial investment in economic infrastructure projects to respond to unemployment, and creating social control over money flow. Furthermore, social democratic parties declared that the Great Depression demonstrated the need for substantial macroeconomic planning while their pro-property rights opponents staunchly opposed this.[85] However attempts by social democratic governments to achieve this were unsuccessful due to the ensuing political instability in their countries from the depression, the British Labour Party became internally split over the policies while Germany's SPD government did not have the time to implement such policies as Germany's politics turned to violent civil unrest in which the Nazis rose to power in 1933 and dismantled parliamentary democracy.[83]

A major development for social democracy was the victories of several social democratic parties in Scandinavia, particularly the Social Democratic Party of Sweden (SAP) in the 1920 Swedish election.[86] The SAP was elected to a minority government. It created a Socialization Committee that declared support for a mixed economy that combined the best of private initiative with social ownership or control, it supported substantial socialization "of all necessary natural resources, industrial enterprises, credit institutions, transportation and communication routes" that would be gradually transferred to the state.[87] It permitted private ownership outside of these areas.[87]

In 1922 Ramsay MacDonald returned to the leadership of the Labour Party from the Independent Labour Party. in the 1924 British election the Labour Party won a plurality of seats and was elected as a minority government but required assistance from the Liberal Party to have a majority of the parliament. Opponents of the Labour Party accused the party of communist sympathies. Prime Minister MacDonald responded to these allegations by stressing the party's commitment to reformist gradualism and openly opposing the radical wing in the party.[88] MacDonald emphasized that the Labour minority government's first and foremost commitment was to uphold democratic responsible government over all other policies. MacDonald emphasized this because he knew that any attempt to pass major socialist legislation in a minority government status would endanger the new government because it would be opposed and blocked by the Conservatives and the Liberals who together held a majority of seats. The Labour Party had risen to power in the aftermath of Britain's severe recession of 1921–1922, with the economy beginning to recover, British trade unions demanded that their wages be restored from the cuts they took in the recession. The trade unions soon became deeply dissatisfied with the MacDonald government and labour unrest and threat of strikes arose in transportation sector, including docks and railways. MacDonald viewed the situation as a crisis, consulting the unions in advance to warn them that his government would have to use strikebreakers if the situation continued. The anticipated clash between the government and the unions was averted, however the situation alienated the unions from the MacDonald government. MacDonald's most controversial action was having Britain recognize the government of the Soviet Union in February 1924. The British Conservative press, including the Daily Mail used this to promote a red scare, claiming that the Labour government's recognition of the Soviet Union proved that Labour held pro-Bolshevik sympathies.[89]

The British Labour Party lost the 1924 election and a Conservative government was elected. Though MacDonald faced multiple challenges to his leadership of the party, the party stabilized by 1927 as a capable opposition party to the Conservative government. MacDonald released a new political programme for the party titled Labour and the Nation (1928). The Labour Party returned to government in 1929, but soon faced the economic catastrophe of the stock market crash of 1929.[89]

In the 1920s, SPD policymaker and Marxist Rudolf Hilferding proposed substantial policy changes in the SPD as well as influencing social democratic and socialist theory. Hilferding was an influential Marxian socialist both in social democracy and outside it, such as his pamphlet titled Imperialism influencing Lenin's own conception of imperialism in the 1910s. Prior to the 1920s Hilferding declared that capitalism had evolved beyond what had been laissez-faire capitalism into what he called "organized capitalism". Organized capitalism was based upon trusts and cartels controlled by financial institutions that could no longer make money within their countries' national boundaries and thus needed to export to survive, resulting in support for imperialism.[90] Hilferding described that while early capitalism promoted itself as peaceful and based on free trade, the era of organized capitalism was aggressive and said that "in the place of humanity there came the idea of the strength and power of the state". He said that this had the consequence of creating effective collectivization within capitalism and had prepared the way for socialism.[91]

Originally Hilferding's vision of a socialism replacing organized capitalism was highly Kautskyan in assuming an either/or perspective, expecting a catastrophic clash between organized capitalism versus socialism. However by the 1920s, Hilferding became an adherent to promoting a gradualist evolution of capitalism into socialism. He then praised organized capitalism for being a step towards socialism, saying at the SPD congress in 1927 that "organized capitalism" is nothing less than "the replacement of the capitalist principle of free competition by the socialist principle of planned production". He went on to say that "the problem is posed to our generation: with the help of the state, with the help of conscious social direction, to transform the economy organized and led by capitalists into an economy directed by the democratic state.".[91]

In the 1930s, the SPD began to transition away from revisionist Marxism towards liberal socialism beginning in the 1930s. After the party was banned by the Nazis in 1933, the SPD acted in exile through the Sopade.[92] In 1934 the Sopade began to publish material that indicated that the SPD was turning towards liberal socialism. Sopade member Curt Geyer was a prominent proponent of liberal socialism within the Sopade, and declared that Sopade represented the tradition of Weimar Republic social democracy - liberal democratic socialism, and declared that Sopade's held true to its mandate of traditional liberal principles combined with the political realism of socialism.[93]

The only social democratic governments in Europe that remained by the early 1930s were in Scandinavia.[83] In the 1930s several Swedish social democratic leadership figures, including former Swedish Prime Minister Rickard Sandler - the secretary and chairman of the Socialization Committee, and Nils Karleby, rejected earlier SAP socialization policies pursued in the 1920s for being to extreme.[87] Karlby and Sanders developed a new conception of social democratic socialism: the Nordic model that called for gradual socialization and redistribution of purchasing power, provision of educational opportunity, support of property rights, permitting private enterprise on the condition that it adheres to the principle that the resources of which it disposes are in reality public means, and the creation of a broad category of social welfare rights.[94] The new SAP government of 1932, replaced the previous government's universal commitment to a balanced budget to a Keynesian-like commitment to a balanced budget within a business cycle. Unlike the 1921–1923 SAP governments that had run large deficits, after a strong increase in state expenditure in 1933, the SAP government reduced Sweden's budget deficit, the government had scheduled Sweden to have its budget deficit eliminated in seven years, however it took only three years to eliminate the deficit and Sweden held a budget surplus from 1936 to 1938. However this policy was criticized because although the budget deficit had been eliminated, major unemployment still remained in Sweden.[95]

In the Americas from the 1920s to 1930s, social democracy was rising as a major political force. In Mexico, several social democratic governments and presidents were elected from the 1920s to the 1930s. The most important Mexican social democratic government of this time was that led by President Lázaro Cárdenas and the Party of the Mexican Revolution whose government initiated agrarian reform that broke up vast aristocratic estates and redistributing property to peasants. Cárdenas was deeply committed to social democracy, but was criticized by his left-wing opponents for being pro-capitalist due to his personal association with a wealthy family and for being corrupt due to his government's exemption from agrarian reform of the estate held by former Mexican President Alvaro Obregón. Political violence in Mexico had become serious in the 1920s with the Cristero War in which right-wing reactionary clericals fought against the left-wing government that was attempting to institute secularization of Mexico. Furthermore, Cardenas' government openly supported Spain's Republican government while opposing Francisco Franco's Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War. During the Spanish Civil War, Cárdenas staunchly asserted that Mexico was progressive and socialist - working with socialists of various types, including communists, and accepted refugees from Spain as well as accepting communist renegade Leon Trotsky as a refugee after Joseph Stalin removed Trotsky and sought to have him killed. Cárdenas strengthened the rights of Mexico's labour movement, nationalized foreign oil companies, and controversially supported peasants in their struggle against landlords by allowing them to form militias to fight the private armies of landlords in the country. Cárdenas' actions deeply aggravated right-wing reactionaries and there was fear that Mexico would succumb to civil war. Cardenas stepped down as Mexican President and supported a compromise presidential candidate who held support from business interests, in order to avoid further antagonizing the right-wing that could have caused a civil war.[96]

Cold War era and Keynesianism, 1945–1979

After World War II, a new international organization to represent social democracy and democratic socialism, the Socialist International in 1951. In the founding Frankfurt Declaration, the Socialist International denounced both capitalism and Bolshevik communism. As for Bolshevik communism, the Declaration denounced it in articles 7, 8, 9, and 10, saying:

- 7. Meanwhile, as Socialism advances throughout the world, new forces have arisen to threaten the movement towards freedom and social justice. Since the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, Communism has split the International Labour Movement and has set back the realization of Socialism in many countries for decades.[97]

- 8. Communism falsely claims a share in the Socialist tradition. In fact it has distorted that tradition beyond recognition. It has built up a rigid theology which is incompatible with the critical spirit of Marxism.[97]

- 9. Where Socialists aim to achieve freedom and justice by removing the exploitation which divides men under capitalism, Communists seek to sharpen those class divisions only in order to establish the dictatorship of a single party.[97]

- 10. International Communism is the instrument of a new imperialism. Wherever it has achieved power it has destroyed freedom or the chance of gaining freedom. It is based on a militarist bureaucracy and a terrorist police. By producing glaring contrasts of wealth and privilege it has created a new class society. Forced labour plays an important part in its economic organization."[97]

The rise of Keynesianism in the Western world during the Cold War influenced the development of social democracy.[98] The attitude by social democracy towards capitalism changed as a result of the rise of Keynesianism.[99] Capitalism was acceptable to social democracy only if capitalism's typical crises could be prevented and if mass unemployment could be averted, Keynesianism was believed to be able to provide this.[99] Social democrats came to accept the market for efficiency reasons, and endorsed Keynesianism that was expected to reconcile democracy and capitalism.[99]

After the 1945 British election, a Labour government was formed by Clement Attlee. Attlee immediately began a program of major nationalizations of the economy.[100] From 1945 to 1951 the Labour government nationalized the Bank of England, civil aviation, cable and wireless, coal, transport, electricity, gas, and iron and steel.[100] This policy of major nationalizations gained clamour from the left faction within the Labour Party that saw the nationalizations as achieving the transformation of Britain from a capitalist to socialist economy.[101] However the Labour government's nationalizations were staunchly condemned by the opposition Conservative Party.[101] The Conservatives defended private enterprise and accused the Labour government of intending to create a Soviet-style centrally planned socialist state.[101] However accusation by the Conservatives of the nationalizations being inspired by Soviet-style central planning this was not the case, as the Labour government's three Chancellors of the Exchequer: Hugh Dalton, Stafford Cripps, and Hugh Gaitskell, all opposed Soviet-style central planning.[101] Initially there were strong direct controls by the state in the economy that had already been implemented by the British government during World War II, however after the war these controls gradually loosened under the Labour government and were eventually phased out and replaced by Keynesian demand management.[101] In spite of opposition by the Conservatives to the nationalizations, all of the nationalizations except for the nationalization of coal and iron soon became accepted in a national consensus on the economy that lasted until the Thatcher era when the national consensus turned towards support of de-nationalization and privatization.[101] The Labour Party lost the 1951 election and a Conservative government was formed.

There were early major critics of the nationalization policy within the Labour Party in the 1950s. British social democratic theorist Anthony Crosland in The Future of Socialism (1956), argued that socialism should be about the reforming of capitalism from within.[102] Crosland claimed that the traditional socialist program of abolishing capitalism on the basis of capitalism inherently causing immiseration, had been rendered obsolete by the fact that the post-war Keynesian capitalism had led to the expansion of affluence for all, including full employment and a welfare state.[103] Crosland claimed that the rise of such an affluent society had resulted in class identity fading, and as a consequence socialism in its traditional conception as then supported by the British Labour Party was no longer attracting support.[103] He claimed that the Labour Party was associated in the public's mind as having "a sectional, traditional, class appeal" that was reinforced by bickering over nationalization.[103] Crosland argued that in order for the Labour Party to become electable again, it had to drop its commitment to nationalization, and to stop equating nationalization with socialism.[103] Instead of this, he claimed that a socialist programme should be about support of social welfare, redistribution of wealth, and "the proper dividing line between the public and private spheres of responsibility".[103]

The SPD in West Germany in 1945 endorsed a similar policy on nationalizations to that of the British Labour government. SPD leader Kurt Schumacher declared that the SPD was in favour of nationalizations of key industrial sectors of the economy, such as: banking and credit, insurance, mining, coal, iron, steel, metal-working, and all other sectors that were identified as monopolistic or cartelized.[104]

India upon becoming a sovereign state in 1947, elected the social democratic Indian National Congress to government with its leader Jawaharlal Nehru becoming Indian Prime Minister. Nehru declared "In Europe, we see many countries have advanced very far on the road to socialism. I am not referring to the communist countries but to those which may be called parliamentary, social democratic countries."[105] In power, Nehru's government emphasized state-guided national development of India, he took inspiration from social democracy, though India's newly formed Planning Commission also took inspiration from post-1949 China's agricultural policies.[106]

The new sovereign state of Israel elected the socialist Mapai party that sought the creation of a socialist economy based on cooperative ownership of the means of production via the kibbutz system while it rejected nationalization of the means of production.[107] The kibbutz are producer cooperatives that with government assistance have flourished in Israel.[108]

In 1959 the SPD instituted a major policy review with the Godesberg Program in 1959.[109] The Godesberg Program eliminated the party's remaining Marxist-aligned policies and the SPD became based upon freiheitlicher Sozialismus (liberal socialism).[109] With the adoption of the Godsberg Program, the SPD renounced Marxist determinism and classism and replaced it with an ethical socialism based on humanism, and emphasized that the party was democratic, pragmatic, and reformist.[110] The most controversial decision of the Godesberg Program was its declaration saying "Private ownership of the means of production can claim protection by society as long as it does not hinder the establishment of social justice".[111] This policy meant the endorsement of Keynesian economic management, social welfare, and a degree of economic planning, and an abandonment of the classical conception of socialism as involving the replacement of capitalist economic system.[111] It declared that the SPD "no longer considered nationalization the major principle of a socialist economy but only one of several (and then only the last) means of controlling economic concentration of power of key industries"; while also committing the SPD to an economic stance to promote "as much competition as possible, as much planning as necessary".[112] This decision to abandon this traditional policy angered many in the SPD who had supported it.[110] With these changes, the SPD enacted the two major pillars of what would become the modern social democratic program: making the party a people's party rather than a party solely representing the working class, and abandoning remaining Marxist policies aimed at destroying capitalism and replacing them with policies aimed at reforming capitalism.[112] The Godesberg Program divorced its conception of socialism from Marxism, declaring that democratic socialism in Europe was "rooted in Christian ethics, humanism, and classical philosophy".[112] The Godesberg Program has been seen as involving the final prevailing of the reformist agenda of Bernstein over the orthodox Marxist agenda of Kautsky.[112]

The Godesberg Program was a major revision of the SPD's policies and gained attention from beyond Germany.[110] At the time of its adoption, in neighbouring France the stance of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) was divided on the Godesberg Program while the French Independent Socialist Party (PSA) denounced the Godesberg Program as "a renunciation of Socialism", and opportunistic reaction to the SPD's electoral defeats.[110]

Response to neoliberalism, contemporary era, 1979 to present

The economic crisis in the Western world during the mid to late 1970s resulted in the rise of neoliberalism and politicians elected on neoliberal platforms such as British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and US President Ronald Reagan. The rise in support for neoliberalism raised questions over the political viability of social democracy, such as sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf predicting the "end of the social democratic century".[113]

In 1985, an agreement was made between several social democratic parties in the Western bloc countries of Belgium, Denmark, and the Netherlands; with the communist parties of the Eastern Bloc countries of Bulgaria, East Germany, and Hungary; to have multilateral discussions on trade, nuclear disarmament and other issues.[114]

In 1989, the Socialist International adopted its present Declaration of Principles. The Declaration of Principles addressed issues concerning the "internationalization of the economy". The Declaration of Principles defined its interpretation of the nature of socialism. It stated that socialist values and vision include "a peaceful and democratic world society combining freedom, justice and solidarity". It defined the rights and freedoms it supported, stating: "Socialists protect the inalienable right to life and to physical safety, to freedom of belief and free expression of opinion, to freedom of association and to protection from torture and degradation. Socialists are committed to achieve freedom from hunger and want, genuine social security, and the right to work." However it also clarified that it did not promote any fixed and permanent definition for socialism, stating: "Socialists do not claim to possess the blueprint for some final and fixed society which cannot be changed, reformed or further developed. In a movement committed to democratic self-determination there will always be room for creativity since each people and every generation must set its own goals."[115]

.jpg)

The 1989 Socialist International congress was politically significant in that members of Communist Party of the Soviet Union during the reformist leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, attended the congress. The SI's new Declaration of Principles abandoned previous statements made in the Frankfurt Declaration of 1951 against Soviet-style communism. After the congress, the Soviet state newspaper Pravda noted that thanks to dialogue between the Soviet Communist Party and the SI since 1979 that "the positions of the CPSU and the Socialist International on nuclear disarmament issues today virtually coincide".[114]

The collapse of the Marxist–Leninist regimes in Eastern Europe after the end of the Cold War, and the creation of multiparty democracy in many many of those countries, resulted in the creation of multiple social democratic parties. Though many of these parties did not achieve initial electoral success, they became a significant part of the political landscape of Eastern Europe. In Western Europe, the prominent Italian Communist Party transformed itself into the post-communist Democratic Party of the Left in 1991.[116]

A highly controversial development in social democracy occurred in the 1990s, with the development of Third Way politics and social democratic adherents of it. The social democratic variant of the Third Way has been advocated by its proponents as an alternative to both capitalism and what it regards as the traditional forms of socialism, including Marxist socialism and state socialism, that Third Way social democrats reject. It officially advocates ethical socialism, reformism, gradualism - that includes advocating the humanized capitalism, a mixed economy, political pluralism, and liberal democracy.[117] Left-wing opponents of Third Way social democracy claim that it is not a form of socialism, and claim that it represents social democrats who responded to the New Right by accepting capitalism.[118] The Third Way has been strongly criticized within the social democratic movement.[119] Supporters of Third Way ideals argue that they merely represent a necessary or pragmatic adaptation of social democracy to the realities of the modern world: traditional social democracy thrived during the prevailing international climate of the post-war Bretton Woods consensus, which collapsed in the 1970s.

Third Way supporter and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair when he was a British Labour Party MP wrote in a Fabian pamphlet in 1994 of the existence of two prominent variants of socialism: one is based on a Marxist economic determinist and collectivist tradition that he rejected, and the other is an "ethical socialism" that he supported, that was based on values of "social justice, the equal worth of each citizen, equality of opportunity, community".[120]

Prominent Third Way proponent Anthony Giddens views conventional socialism as essentially having become obsolete. However Giddens claims that a viable form of socialism was advocated by Anthony Crosland in his major work The Future of Socialism (1956).[121] Giddens has complimented Crosland as well as Thomas Humphrey Marshall for promoting a viable socialism.[122] Giddens views what he considers the conventional form of socialism - state socialism - that defines socialism as a theory of economic management, as no longer viable.[123] Giddens rejects what he considers top-down socialism as well as rejecting neoliberalism.[117] Giddens criticizes conventional socialism for its common advocacy that socialization of production, as achieved by central planning, can overcome the irrationalities of capitalism. Giddens claims that this claim "can no longer be defended". He says that with the collapse of legitimacy of centrally planned socialization of production, "With its dissolution, the radical hopes for by socialism are as dead as the Old Conservatism that opposed them". Giddens says that although there have been proponents of market socialism who have rejected such central planned socialism as well as being resistant to capitalism, that "There are good reasons, in my view, to argue that market socialism isn't a realistic possibility". Giddens makes clear that Third Way as he envisions it, is not market socialist and says "There is no Third Way of this sort, and with this realization the history of socialism as the avant-garde of political theory comes to a close.".[121]

However Giddens contends that Third Way is connected to the legacy of reformist revisionist socialism, saying "Third way politics stands in the traditions of social democratic revisionism that stretch back to Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky."[124]

Giddens commends Crosland's A Future of Socialism for recognizing that socialism cannot be defined merely in terms of a rejection of capitalism, because if capitalism did end and was replaced with socialism, then socialism would have no purpose with the absence of capitalism.[125] From Crosland's analysis, Giddens proposes a description of socialism:

The only common characteristic of socialist doctrines is their ethical content. Socialism is the pursuit of ideas of social cooperation, universal welfare, and equality - ideas brought together by a condemnation of the evils and injustices of capitalism. It is based on the critique of individualism and depends on a 'belief in group action and "participation", and collective responsibility for social welfare'.—Anthony Giddens, Beyond Left and Right: The Future of Radical Politics.[126]

.jpg)

Paul Cammack has condemned the Third Way as conceived by Anthony Giddens as being a complete attack upon the foundations of social democracy and socialism in which Giddens has sought to replace them with capitalism. Cammack claims that Giddens devotes more energy into criticizing conventional social democracy and conventional socialism, including Giddens' claim that conventional socialism has "died" because Marx's vision of a new economy with wealth spread in an equitable way is not possible, while at the same time making no criticism of capitalism. As such, Cammack condemns Giddens and his Third Way for being anti-social-democratic, anti-socialist, and pro-capitalist that Giddens disguises in rhetoric to make appealing within social democracy.[127]

British political theorist Robert Corfe who was in the past a social democratic proponent of a new socialism free of class-based prejudices, criticized both Marxist classists and Third Way proponents within the Labour Party.[128] Corfe has denounced the Third Way as developed by Giddens for "intellectual emptiness and ideological poverty".[129] Corfe has despondently noted and agreed with former long-term British Labour Party MP Alice Mahon's statement in which she said "Labour is the party of bankers, not workers. The party has lost its soul, and what has replace it is harsh, American style politics..." Corfe claims that the failure to develop a new socialism has resulted in what he considers the "death of socialism" that left social capitalism as only feasible alternative.[130]

Former SPD chairman Oskar Lafontaine condemned then-SPD leader and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder for his Third Way policies, saying that the SPD under Schröder had adopted "a radical change of direction towards a policy of neoliberalism".[131] After resigning from the SPD, Lafontaine co-founded The Left in 2007.[132] The Left was founded out of a merger of the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative (WASG) - a breakaway faction from the SPD. The Left has been controversial because as a direct successor to the PDS, it is also a direct successor of former East Germany's ruling Marxist–Leninist Socialist Unity Party (SED) that transformed into the PDS after the end of the Cold War. However the PDS did not continue the SED's policies, as the PDS adopted policies to appeal to democratic socialists, greens, feminists, and pacifists.[133] Lafontaine said in an interview that he supports the type of social democracy pursued by Willy Brandt but claims that the creation of The Left was necessary because "formerly socialist and social democratic parties" had effectively accepted neoliberalism.[132] The Left grew in strength and in the 2009 German parliamentary election gained 11 percent of the vote while the SPD gained 23 percent of the vote.[133]

Lafontaine has noted that the founding of The Left in Germany has resulted in emulation in other countries, with several Left parties being founded in Greece, Portugal, Netherlands, and Syria.[134] Lafontaine claims that a de facto British Left movement exists, identifying British Green Party MEP Caroline Lucas as holding similar values.[135]

Others have claimed that social democracy needs to move past the Third Way, such as Olaf Cramme and Patrick Diamond in their book After the Third Way: The Future of Social Democracy in Europe (2012).[136] Cramme and Diamond recognize that the Third Way arose as an attempt to break down the traditional dichotomy within social democracy between state intervention and markets in the economy, however they contend that the global financial crisis of the late 2000s requires that social democracy must rethink its political economy. Cramme and Diamond note that optimism in economic planning amongst socialists was strong in the early to mid-twentieth century, but declined with the rise of the neoliberal right that both attacked economic planning and associated the left with economic planning. They claim that this formed the foundation of the "Right's moral trap" in which the neoliberal right attacks on economic planning policies by the left, that provokes a defense of such planning by the left as being morally necessary, and ends with the right then rebuking such policies as being inherently economically incompetent while presenting itself as the champion of economic competence.[137] Cramme and Diamond state that social democracy has four different strategies both to address the economic crisis in global markets at present that it could adopt in response: market conforming, market complimenting, market resisting, market substituting, and market transforming.[138]

Cramme and Diamond identify market conforming as being equivalent to historic social democratic policymaker Philip Snowden's desire for a very moderate socialist agenda based above all upon fiscal prudence, as Snowden insisted that socialism had to build upon fiscal prudence or else it would not be achieved.[139]

Criticism

Critics of contemporary social democracy such as Jonas Hinnfors argue that when social democracy abandoned Marxism it also abandoned socialism and has become in effect a liberal capitalist movement,[140] in effect making social democrats similar to centre-left, but pro-capitalist groups, such as the U.S. Democratic Party.

Marxian socialists of the classical, orthodox and analytical variations argue that because social democratic programs retain the capitalist mode of production, they also retain the fundamental issues of capitalism, including cyclical fluctuations, exploitation and alienation. Social democratic programs intended to ameliorate capitalism, such as unemployment benefits, taxation on profits and the wealthy, create contradictions of their own by limiting the efficiency of the capitalist system by reducing incentives for capitalists to invest in production.[141]

Democratic socialists, such as David Schweickart, contrast social democracy with democratic socialism by defining the former as an attempt to strengthen the welfare state, and the latter as an alternative socialist economic system to capitalism. According to Schweickart, the democratic socialist critique of social democracy states that capitalism could never be sufficiently "humanized", and any attempt to suppress the economic contradictions of capitalism would only cause them to emerge elsewhere. For example, attempts to reduce unemployment too much would result in inflation, and too much job security would erode labour discipline.[142] In contrast to social democracy, democratic socialists advocate a post-capitalist economic system based either on market socialism combined with workers self-management, or on some form of participatory-economic planning.[143]

Market socialists contrast social democracy with market socialism. While a common goal of both systems is to achieve greater social and economic equality, market socialism does so by changes in enterprise ownership and management, whereas social democracy attempts to do so by government-imposed taxes and subsidies on privately owned enterprises. Frank Roosevelt and David Belkin criticize social democracy for maintaining a property-owning capitalist class, which has an active interest in reversing social democratic policies and a disproportionate amount of power over society to influence governmental policy as a class.[144]