Slowly varying envelope approximation

In physics, the slowly varying envelope approximation (SVEA) is the assumption that the envelope of a forward-travelling wave pulse varies slowly in time and space compared to a period or wavelength. This requires the spectrum of the signal to be narrow-banded—hence it also referred to as the narrow-band approximation.

The slowly varying envelope approximation is often used because the resulting equations are in many cases easier to solve than the original equations, reducing the order of—all or some of—the highest-order partial derivatives. But the validity of the assumptions which are made need to be justified.

Example

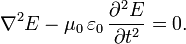

For example, consider the electromagnetic wave equation:

If k0 and ω0 are the wave number and angular frequency of the (characteristic) carrier wave for the signal E(r,t), the following representation is useful:

where  denotes the real part of the quantity between brackets.

denotes the real part of the quantity between brackets.

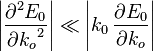

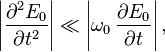

In the slowly varying envelope approximation (SVEA) it is assumed that the complex amplitude E0(r, t) only varies slowly with r and t. This inherently implies that E0(r, t) represents waves propagating forward, predominantly in the k0 direction. As a result of the slow variation of E0(r, t), when taking derivatives, the highest-order derivatives may be neglected:[1]

and

and  with

with

Full approximation

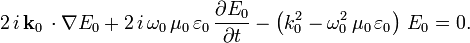

Consequently, the wave equation is approximated in the SVEA as:

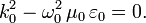

It is convenient to choose k0 and ω0 such that they satisfy the dispersion relation:

This gives the following approximation to the wave equation, as a result of the slowly varying envelope approximation:

Which is a hyperbolic partial differential equation, like the original wave equation, but now of first-order instead of second-order. And valid for coherent forward-propagating waves in directions near the k0-direction.

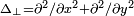

Parabolic approximation

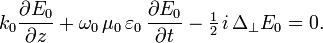

Assume wave propagation is dominantly in the z-direction, and k0 is taken in this direction. The SVEA is only applied to the second-order spatial derivatives in the z-direction and time. If  is the Laplace operator in the x–y plane, the result is:[2]

is the Laplace operator in the x–y plane, the result is:[2]

Which is a parabolic partial differential equation. This equation has enhanced validity as compared to the full SVEA: it can represents waves propagating in directions significantly different from the z-direction.

See also

References

- ↑ Butcher, Paul N.; Cotter, David (1991). The elements of nonlinear optics (Reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 0-521-42424-0.

- ↑ Svelto, Orazio (1974). "Self-focussing, self-trapping, and self-phase modulation of laser beams". In Wolf, Emil. Progress in Optics 12. North Holland. pp. 23–25. ISBN 0-444-10571-9.