Sleepy Hollow Country Club

| |

| Club information | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1911 |

| Type | Private |

| Total holes | 27 |

| Website | |

|

Sleepy Hollow Country Club | |

.png) Map of the Scarborough Historic District; country club land is green | |

| Location | 777 Albany Post Road (US 9), Scarborough, New York 10510 |

| Coordinates | 41°07′34.8″N 73°51′14.7″W / 41.126333°N 73.854083°WCoordinates: 41°07′34.8″N 73°51′14.7″W / 41.126333°N 73.854083°W |

| Area | 338 acres (0.5 sq mi) |

| Built | 1892–5 |

| Architect | McKim, Mead & White (Mead supervising) |

| Architectural style | English Renaissance Revival |

| Part of | Scarborough Historic District (#84003433[1]) |

| Added to NRHP | September 7, 1984[1] |

| |

Sleepy Hollow Country Club is a historic country club in Scarborough-on-Hudson in Briarcliff Manor, New York. The country club is a contributing property to the Scarborough Historic District. The club was founded in 1911, and its clubhouse was known as Woodlea, a 140-room $2 million ($52.5 million today[2]) Vanderbilt mansion owned by Colonel Elliott Fitch Shepard and his wife Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard. It was built in 1892–5 and designed by the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White.

Club

.png)

The club currently has 338 acres (0.5 sq mi) and a 27-hole golf course with tree limb footbridges.[3] Facilities include the main clubhouse, a pool complex, ten Har-Tru tennis courts, four aluminum heated platform tennis courts, four squash courts, eighteen guest rooms, skeet and trap areas, a 45-horse boarding facility, twenty paddocks, a large indoor riding arena, a pro shop for golf and paddle sports, a fitness complex,[4] the golf course and practice range (non-contributing), outdoor riding rings, stables, and a carriage house.[5] Youth activities include golf, tennis, squash and riding.[4] The clubhouse has three dining rooms, and altogether the club can hold 400 guests.[4][6] The club currently has 570 members, employs 60 year-round, and 200 during the height of the season.[4] The stables have a tack room, fifty stalls, and two indoor arenas, and they host the Sleepy Hollow Stable and Riding Academy.[6] The club's gross revenue is $12 million; of it, $2.5 million is from food and beverage sales.[4] The club property surrounds Saint Mary's Episcopal Church on three sides and slopes upwards east from U.S. Route 9. The clubhouse, which is open through every season of the year,[4] sits on a wide central plateau.[5] Notable current members include Bill Murray, James Patterson, and several members of the Rockefeller family.[7]

History

.jpg)

Name

Sleepy Hollow Country Club, founded in 1910, predates the 1996 renaming of the neighboring village of North Tarrytown to Sleepy Hollow. The club is named after its location in the river valley of the Pocantico River, a river which was once called "Slapershaven" (Sleepers' Haven); the name later grew to apply to the valley. Contemporarily, the name geographically refers only to the village of Sleepy Hollow.[8](p316)[9]

19th century

Sleepy Hollow's clubhouse was once the private residence named Woodlea. The mansion retained the name of a former house of J. Butler Wright, who lived there and called it Woodlea; it dates to around 1806.[10] Wright's Victorian house, of painted-brick with porches and a high tower on one end,[11](p158) was later renamed the Villa.[11](p161) Colonel Elliott Fitch Shepard came to the Briarcliff area in the early 1890s,[11](p158) and having purchased the house and its 500-acre (0.8 sq mi) property,[10] ordered construction of the existing house and improvements to the grounds. Construction on the mansion began in 1892,[5] and it was completed in 1895.[11](p153) Shepard died in 1893, leaving his wife Margaret to oversee the completion of Woodlea.[11](pp159–60) After his death, Margaret lived there only during spring and autumn,[11](p165) with less and less frequent trips. By 1900, she began selling property to Frank Vanderlip and William Rockefeller, and she sold the house to the two men in 1910. Vanderlip thought of it as too big of a bargain to pass up – the Shepards had already spent $2 million ($50.6 million today[2]) on the property,[11](p165) and Margaret had offered it for only $165,000 ($4,176,300 today[2]). Narcissa Vanderlip thought the house too large and grand to live in, and so the Vanderlips stayed in their nearby property of Beechwood.[11](p160)

20th century to the present

The two men assembled a board of directors to form a country club, including future Titanic victim John Jacob Astor IV, coal baron Edward Julius Berwind, cotillion leaders Elisha Dyer and Lispenard Stewart, and sportsmen W. Averell Harriman, Cornelius Vanderbilt III, and Harrison A. Williams.[11](p160)[nb 1] The country club was incorporated on May 11, 1911. The directors' first meeting took place at Vanderlip's office at 55 Wall St., the National City Bank Building (Vanderlip was the president of the bank at the time). Initiation and yearly dues were each $100 ($2,500 today[2]). For the first few years, the club rented Woodlea for $25,000 ($632,800 today[2]) a year, and in 1912, the club purchased the property from Vanderlip and Rockefeller for $350,000 ($8,553,300 today[2]). The club then constructed the golf course in close harmony to the existing lawns, and also built an outdoor garden theater with clipped cedars and a 16th-century Italian portal. The club ended up paying $310,000 for the land and house, and spent another $100,000 on improvements.[13] The grounds had been designed by the sons of Frederick Law Olmsted from 1895 to 1901;[11](p160) the club had Charles B. Macdonald design the first golf couse, and A. W. Tillinghast designed an update in 1935, succeeded by Gil Hanse's redesign from 18 to 27 holes around 2008.[6][14](p79)

In 1917, the club had had 1,000 members, and its president was Frank Vanderlip.[13] In June of that year, William Rockefeller purchased 387 acres (0.6 sq mi) for the club, bringing its area to 480 acres (0.8 sq mi) (the house was originally sold with only 93 acres (0.1 sq mi)). Rockefeller spent $600,000 ($11,044,700 today[2]), making it the largest single real estate transaction in the county.[13] New facilities were built in the 1920s, including a manager's house, skeet house, squash house, indoor riding ring, and swimming pool. The old Butler Wright house became the golf house; it was demolished in 1967.[11](p169) The club had operated at a loss from the beginning, and after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, club members were not successful in maintaining their wealth, and membership declined. Cuts were made—horses were sold, Woodlea was closed except for special occasions, and the golf house became the primary clubhouse. 5-acre (0.008 sq mi) building lots north of Woodlea were sold to members. The club was also not successful during World War II and later; in 1950, a member could stay overnight at Woodlea for $5 ($49 today[2]), and for less in the golf house. The first formal dance that year also cost $5 a person. In 1961, Woodlea was redecorated with modern fabrics, warm gold and forest green carpets, dropped lighting, and some lowered ceilings.[11](p167)

In the 1960s, the club demolished the golf house and built a golfing and meal facility in an addition to Woodlea. Original to the house, and occupying its northeast terrace against its service wing, was an Italian garden with vine-clad pergolas on each side, symmetrical gravel paths,[11](p164) marble benches, long stone balustrades, and a pool with a fountain in the middle.[11](p165) The garden was also demolished in the 1960s, and it was replaced with a modern building for locker rooms, the club's pro shop, and dining facilities. The structure was designed to be spacious and convenient, and to not be noticeable from the grounds below, although from Woodlea, the sight of the tar roof and ventilators was noted to be worse than the prior standing gardens.[11](pp167–8) In 2014, the country club expanded and renovated the snack bar building, renovated the locker room building exterior, constructed a large array of solar panels on the roof of the locker room and dining facility building, and performed other renovations.[15]

The formal garden was to the house’s north and below the river front. It was built against the hillside and occupies a portion of a slope that falls far below it. It has characteristics of a hanging garden. The lower walls of the house are screened with a row of large cedars planted on the highest part of the garden. A large plateau or terrace was built on the hillside, which the garden occupies. The garden formed by an immense rectangular space, on the four sides there are pergolas thickly overgrown with vines. In the center is a pool and fountain. Walks and beds of flowers and shrubbery occupy the rest, visible from the windows of the river front.[10]

Architecture

Woodlea

.png)

The architect of Woodlea is variously stated as McKim, Mead & White,[5][6] and Stanford White,[16][17] although according to William Mitchell Kendall in his 1920 list of the firm's works, he attributes the house's design to McKim, Mead & White, with W. R. Mead as the supervising architect.[11](pp153, 161)

Exterior

.tif.png)

Woodlea's exterior was designed in an English Renaissance Revival style. The house is said to have been modeled after Kimberley Hall in Kimberley, Norfolk.[18] Its classical devices of 18th-century English architecture include urns, pediments, columns, and balusters. The house also is a full-blown expression of the American Renaissance.[11](p162) Woodlea follows characteristics of the Beaux-Arts—the exterior dictates the use of the interior, with family and guest rooms in the third floor portion, and servant quarters in the service wing, which has lower ceilings, smaller windows, less exterior trim, and is the farthest wing from the house's primary approach. The wing is situated at the house's north; it is larger than most houses.[10] In the early 1900s, the wing was clad in ivy.[11](p164)

Woodlea is constructed of buff-colored pressed brick with pale stone trim.[11](p161) It is three stories tall,[19] seven bays wide, and more than fourteen bays deep. The south and west facades are both symmetrical, although the house has an asymmetrical overall plan. The house has pedimented pavilions and entrance porticos on the west, south, and east; window trim consisting of stone surrounds, pediments, lintels, and sills; classical balusters and quoins. The house's third story is separated visually by a stone string course and is topped with a modillioned cornice. From a shallow hipped roof rise brick chimneys that are trimmed and capped with stone. The pavilion pediments have decorative urn-shaped elements. The house's windows are primarily rectangular, double hung, one-over-one panel style, except for a large triple Palladian window, which has stained glass and is situated midway up the house's main staircase, illuminating its lower steps.[5][10] The house has distinctive quoins, pediments, and classical balustrades of pale gray limestone.[11](p161)

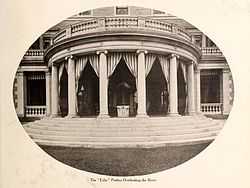

The long axis of the house is the most ornate;[10] it faces the Hudson River, with a view of the river from its terrace and west-facing windows.[6] The curtain wall between the facade's pavilions contains a semicircular portico, and its entablature is upheld by Ionic columns, and supports a balustrade. A flight of semicircular steps descends to the terrace. The river front is parallel with the east front, which had a porte-cochère, a minor entrance, and a service entrance.[10] The south doors are the main entrance,[11](p163) directly approached by the south drive.

The house has between 65,000 and 70,000 square feet (6,500 m2), making it one of the largest houses in the U.S.[4][11](p163)[20] The property has about three miles of wide driveways.[10][11](p161)

Interior

(formerly the dining room, parlor, and living room)

The house also has significant interior features, including marble fireplaces, wood paneling, coffered ceilings, window and door architraves, parquet floors, and extensive carved wood and plaster detail, primarily in the Adamesque mold.[5]

In 1906, the house had 16 bathrooms and 65 rooms, including 20 for servants. The house's main door opens into a square vaulted vestibule, walled throughout with highly polished yellow marble. It leads into the main hall. The main hall is paneled to the ceiling in wood, painted white, the corners and angles accentuated by pilasters, and the rich mahogany doors encased within monumental frames. The white ceiling is intricately coffered. The hall has a large fireplace of carved white marble and a large table in the room’s center, which was on a large red rug covering most of the floor. The first floor also has an enfilade of three rooms: the green silk- and cedar-paneled living room, the white and gold drawing room, and the dark mahogany dining room. The three rooms have a span or linear distance of over 150 feet.[11](p163) A corridor connects the main hall to three rooms; it has recessed windows, dividing the corridor into bays. The corridor has pilasters and the coffered ceiling of the main hall, and used to have heavy velvet curtains at the window alcoves and entrance to the hallway; the windows had curtains of delicate salmon silk.[10]

The first room from the corridor was the living room, with cedar wood, a wainscot, pilasters, cornice, and door and window frames all of cedar. Walls are paneled in green silk, mirroring the rug and furnishings. The drawing room, music room, or parlor was at the center, with paneled walls in ivory white and gold, with gilded moldings and ornaments. There are richly interlaced panels above the doorways with paintings inserted in them. The mantle is of mottled purple and white marble, and has a built-in mirror above it. The room has richly gilt chandeliers hanging from ornamental reliefs in the otherwise plain ceiling. Furniture was of tapestry and gold, with a light rug and yellow and gold curtains at the windows and doors.[10]

The dining room had a high wainscot of mahogany, paneled in rectangles, above which is a broad tapestry frieze. The ceiling is beamed with closely set beams, and the cornice is mahogany like the other woodwork. The room is lighted by the cluster of lights applied to the wainscot. The house's pantry was "as large as many New York apartments", had a counter and wash bowls and large rows of glazed closets around other walls. The kitchen and serving room had a refrigerator and were well stocked and equipped. The breakfast room was green and white, woodwork painted white, walls covered in Nile green cloth; it had a wood mantel with facings of mottled white marble. Adjoining is the morning-room, finished in quartered oak, with walls papered in red stripes of two shades, has a quartered oak wainscot and white cornice, curtains and furniture are red and gold.[10]

The library is on the right of the hall, removed from the other rooms; it had a billiard table. The walls are lined with tall bookcases, and were otherwise covered in large square panel-like pieces of leather. The room has a richly coffered ceiling and had green and brown curtains. The house has bedrooms of various sizes, most large, with Mrs. Shepard's the biggest. Each room has distinct furnishings and from moderate to rich decoration. One particular was the Moorish room, furnished in the Moorish style, with mantel and furniture inlaid with mother of pearl. The third floor had bedrooms, a children's suite and a large playroom.[10]

The house's room arrangement was planned for convenience and comfort, as compared to typical English mansions, which often were built with kitchens far from the dining room. Woodlea has 140 rooms,[21] which were designed to be neither drafty nor for important rooms to be too remote. The rooms are all over-scaled in terms of the height of the ceilings and size of the doors, large fireplaces, and the length and breadth of the stairway to the house's second floor.[11](p163)

Stable

The stable was designed by McKim, Mead & White and built in the late 19th century using the same yellow brick used for the main residence. The stable is two and a half stories high, 29 bays wide, and 5 bays deep, and it has a gable roof covered with asbestos shingles that replaced its original ceramic tile. On the roof's ridge sits a shallow monitor, flanked by two taller octangular monitors with louvered ventilating elements and bell-cast copper roofs.[5]

The end bays of the west (main) facade are framed in pedimented pavilions, which have recessed brick panels above the impost line, and below it are bricks coursed to resemble rustication. One glazed roundel is at the middle of each tympanum. The pedimented central bay has an arched recessed entrance with a pair of oversized double wood doors beneath a fanlight. The arch is flanked with blind roundels above the impost line, with rustication below. The bay's tympanum is undecorated. The arch impost line continues as a belt course between the pavilions and forms the sills for recessed wood-framed, fixed-sashed, nine-light windows on the building's second level. The windows are divided by Doric pilasters.[5]

Fenestration at the main facade's lower level is only narrow wood-framed double-hung glazed embrasures with two-over-two sash. The facades have a denticulated cornice, repeated within the pediments and arched pavilion lintels. The stable is built into a hill, and has a partial basement level with 51 stalls.[5]

The two-story interior space on the first floor was originally used for carriages and then for automobiles, and now is used as an indoor exercising ring for the horses occupying the stalls below. In the end pavilions, there is a reception area, tack room, and small apartment designed to be occupied by the riding instructor.[5]

Gatehouses

Both of the country club's Route 9 entrances have a gatehouse. Both are small, two stories high, three bays wide, and one bay deep, and were constructed along with the house in the 1890s. The gatehouses resemble Woodlea in materials and simplified stylistic detail. Both gatehouses have gable roofs and a shed-roofed one-story high rear addition. The houses have stone and brick pedimented porticos over their entranceways. The lower-level windows have flat-arched surrounds with keystones; the oculi break the cornice lines beneath segmentally arched pediments. The northern gatehouse has another one-story rear addition and a small one-car garage.[5] The club's gates are made of French-imported carved stone and ironwork.

Pool house

The pool house was built in the 1970s and is brick with wood-framed casement windows. It is a divided brick building with locker rooms on the larger west section and a refreshment area on the smaller east section. The west section has a flat roof, and the east section has a shallow hipped roof with a broad overhang. The building does not contribute to the former historic estate.[5]

Skeet house

The skeet house was built around 1925, and is a small one-story log building, three bays wide and one bay deep with a gable roof. The interior is rustic, with a small kitchen and one large multi-purpose room. The building contributes to the estate's early 20th century development.[5]

Logan Memorial Riding Ring

The riding ring was built around 1920. Its exterior is stucco over concrete block; the building has a main section with a round-arched asbestos-shingled roof, and is two stories high, five bays wide, and ten bays deep. The building has narrow metal-framed tripartite casement windows with brick sills. The upper, eight-light sections of the windows open horizontally, and the lower portions with sixteen lights open vertically; the central twenty-light sections are fixed. The structure's bays are divided on the side facades by sloping concrete ground-to-cornice buttresses, paired at the intersections of the side and rear facades.[5]

The main (west) facade has a projecting two and a half-story gable roof section that is three bays wide and two deep. Decorative detail on the exterior includes quoins, the James Gibbs-inspired surround on the main entrance, and the molded surrounds and keystones of the casement windows. In the northwest corner of the intersection between the building's two sections is a one-story-high, one-bay-square addition with a narrow metal casement window on the west facade and a large double entrance for horses on the north.[5] The building's interior consists of a large riding ring that is open to the rafters, and in the gable-roofed section, there are lockers and changing rooms on the first floor and a multi-purpose room on the second; on one of its walls is a floor-to-ceiling window permitting view of the ring activity below.[5]

Squash house

The squash house was also constructed around 1920, and was demolished between 2011 and 2013. It was two stories high, five bays wide and nine bays deep, and was stucco-covered with a flat roof. There were two entrances on the main (south) facade, one at ground level and another on the balcony. The entrances had double wooden doors, paneled below and glazed above. All of the building's windows consisted of wood-framed, paired casement windows with brick sills. A veranda with Tuscan piers extended the length of the main facade, interrupted by a two-bay-wide, one-bay-deep projection east of the main entrance. The building's interior contained a doubles court, two singles courts, a reception room, locker rooms, and a spectators' gallery. Across the road from where the building stood is an outdoor riding ring enclosed by a rough rail fence. To the west of the building's site, standing alone in the tall grass, is a 16th-century post-and-lintel stone element, which was at the center of the stage of an outdoor Greek theater that was part of the Shepard estate and was since dismantled.[5]

Former manager's house

The manager's house was built of brick and stucco around 1920. It is two stories high, four bays wide, two bays deep, and has an asymmetrical plan. The building has a shallow hip roof with exposed rafter ends. Its windows are primarily one-over-one and double-hung with wood trim, with window-sills made of concrete. There is a three-story rectangular brick tower set into the main (west) facade. The tower is open at the top beneath a wide wood fascia. The building has a brick chimney decorated with corbelling; its chimney coping and caps are made of concrete. The building now is rented to the members.[5]

Carriage barn complex

The carriage barn complex predates the Shepards' ownership of the property; it was built around 1875 as part of Wright's original estate. The most prominent component is the brick carriage house, which was designed by McKim, Mead & White.[11](p161) It is made of brick with granite trim and is one and a half stories high, ten bays wide and three bays deep. It has a steeply pitched slate hip roof with spring eaves and exposed rafters. At the roof's ridge sits an octagonal ventilating element with a bell-cast roof.[5]

On the main (north) facade, there is a two-bay-wide projection with a hip roof and two wall dormers. There is a large roof dormer on the side (east) facade which provides exterior access to the hayloft. Other fenestration includes small square windows with fixed sashes near the eaves on all facades and four double-hung windows, two per level, in the main facade's pavilion. Each end facade has a set of large double wood carriage doors. The complex now serves as a storage and maintenance facility for the club's golf carts.

Opposite the carriage barn is another building, also of brick but with a low hip roof. It is one story high, one bay deep and five bays wide. There are three sets of overhead doors on the main (south) facade of the building. A high brick wall encloses the entire complex, and sections of the corner utility structures are a part of the surrounding wall. There is a small building in the northeast corner of the complex; it is one bay square with a steep hip roof with spring eaves. It has single round windows near the root line, on two facades. The building's entrance, on the south facade, is made of wood. The building has a counterpart across the yard, with a low hip roof, a large brick chimney, and a stone water table and string course; it has overhead doors on the north facade.[5]

Popular culture

In the 2011-2 television show Pan Am, Sleepy Hollow Country Club was the setting for much of the series' third episode.[22][23] Other media filmed at the country club include the 2012 show 666 Park Avenue, 2009-present show The Good Wife, the 2009 film The Six Wives of Henry Lefay, the 2006–13 show 30 Rock, the 2009 television special Michael J. Fox: Adventures of an Incurable Optimist, 2010 film The Bounty Hunter,[24] and the music video of Beyoncé's 2011 song "Best Thing I Never Had".[24]

.tif.png)

Scorecard

| Tee | Rating/Slope | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Out | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | In | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | M-73.8/135 | 417 | 372 | 167 | 422 | 441 | 475 | 217 | 462 | 425 | 3398 | 172 | 433 | 541 | 394 | 413 | 502 | 155 | 446 | 426 | 3482 | 6880 |

| White | M-72.0/132 | 406 | 321 | 153 | 404 | 403 | 458 | 193 | 439 | 377 | 3154 | 156 | 371 | 513 | 384 | 378 | 437 | 150 | 433 | 401 | 3223 | 6377 |

| Green | M-69.1/131 | 402 | 312 | 153 | 343 | 393 | 413 | 179 | 350 | 361 | 2906 | 136 | 361 | 475 | 304 | 359 | 430 | 134 | 375 | 385 | 2959 | 5865 |

| Handicap | Men's | 12 | 10 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 4 | 14 | 15 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 13 | 7 | 17 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Par | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 35 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 35 | 70 | |

| Handicap | Women's | 12 | 10 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 4 | 14 | 15 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 13 | 7 | 17 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Green | L-74.6/135 | 402 | 312 | 153 | 343 | 393 | 413 | 179 | 350 | 361 | 2906 | 136 | 361 | 475 | 304 | 359 | 430 | 134 | 375 | 385 | 2959 | 5865 |

| Red | L-72.5/130 | 397 | 279 | 146 | 341 | 383 | 406 | 175 | 424 | 321 | 2872 | 119 | 323 | 401 | 298 | 277 | 345 | 134 | 371 | 380 | 2648 | 5520 |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Other sources list other men, including Cornelius Vanderbilt, V. Everit Macy, and Edward Harden;[5] James Stillman and Oliver Harriman, uncle of E. H. Harriman;[12] and George W. Perkins, Samuel Sloan, and Edward J. Berwind.[13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2014. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ↑ Gould, David (August–September 2011). "Treasure on the Hudson". The Met Golfer (The Metropolitan Golf Association) 29 (4): cover, 57–61. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Sleepy Hollow Country Club – Scarborough, New York: General Manager". Texas Lone Star Chapter of the Club Manager's Association of America. Denehy Club Thinking Partners. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination form - Scarborough Historic District". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Diedrich, Richard (2007). The 19th Hole: Architecture of the Golf Clubhouse. Mulgrave , Vic.: The Images Publishing Group. pp. 90–5. ISBN 978-1-86470-223-1. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ↑ Rogers, Paul (August 7, 2011). "Carrying the Clubs, and Using Them". The New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ↑ Bolton, Jr., Robert (1848). A History of the County of Westchester, From its First Settlement to the Present Time. New York: Alexander S. Gould. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ↑ Steiner, Henry. "History of the Village". Village of Sleepy Hollow. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 10.10 10.11 Ferree, Bar (December 1906). "Notable American Homes". American Homes and Gardens (New York: Munn and Company) 3 (6): 355–364. LCCN 06022575. OCLC 1479984. OL 25515598M. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 11.18 11.19 11.20 11.21 11.22 11.23 11.24 11.25 Foreman, John; Stimson, Robbe Pierce (May 1991). "7". The Vanderbilts and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations, 1879–1901 (1st ed.). New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 152–169. ISBN 0-312-05984-1. LCCN 90027083. OCLC 22957281.

- ↑ Williams, Gray (2003). Picturing Our Past: National Register Sites in Westchester County. Elmsford, New York: Westchester County Historical Society. ISBN 0-915585-14-6.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "Club's $600,000 Purchase.". The New York Times. June 17, 1917. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ↑ Cheever, Mary (1990). The Changing Landscape: A History of Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough. West Kennebunk, Maine: Phoenix Publishing. ISBN 0-914659-49-9. LCCN 90045613. OCLC 22274920. OL 1884671M.

- ↑ "Board of Trustees Minutes 03/05/2014". Village of Briarcliff Manor. March 5, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Our Village: a family place for more than a century". Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ Gelard, Donna (2002). Explore Briarcliff Manor: A driving tour. Contributing Editor Elsie Smith; layout and typography by Lorraine Gelard; map, illustrations, and calligraphy by Allison Krasner. Briarcliff Manor Centennial Committee.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Magazine". November 1898.

- ↑ van Court, Robert H. (August 1914). "The Famous Sleepy Hollow Club". Suburban Life, the Countryside Magazine (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Suburban Press) XIX: 59–61. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ↑ Finan, Tom. "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow Rides On". Club Management (August 2004). Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ↑ Our Village: Briarcliff Manor, N.Y. 1902 to 1952. Historical Committee of the Semi–Centennial. 1952.

- ↑ Studley, Sarah (October 31, 2011). "Hollywood Comes to Briarcliff Manor". Pleasantville-Briarcliff Manor Patch. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ Studley, Sarah (August 18, 2011). "New TV Show 'Pan Am' Shoots at SH Country Club". Tarrytown-Sleepy Hollow Patch. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Turiano, John Bruno (September 2011). "Sleepy Hollow Country Club General Manager William Nitschke on Pop Star Beyoncé Knowles' Appearance to Shoot her "Best Thing I Never Had" Music Video". Westchester Magazine. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

Further reading

| Library resources about Sleepy Hollow Country Club |

- Ferree, Bar (December 1906). "Notable American Homes". American Homes and Gardens (New York: Munn and Company) 3 (6): 355–364. LCCN 06022575. OCLC 1479984. OL 25515598M. Retrieved August 11, 2014. For more information on the house and its gardens.

External links

|

| Preceded by Various |

Host of the Metropolitan Amateur 1944, 1965, 1983 |

Succeeded by Various |

| Preceded by Newport Country Club |

Host of the NYNEX Commemorative 1986–1993 |

Succeeded by None (event closed) |

| Preceded by Flint Hills National Golf Club |

Host of the U.S. Women's Amateur Golf Championship 2002 |

Succeeded by Philadelphia Country Club |

| Preceded by Bethpage Black Course |

Host of the Metropolitan Open 2011 |

Succeeded by Plainfield Country Club |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||