Slash-and-burn

|

| Agriculture |

|---|

| General |

|

| History |

| Types |

| Categories |

|

| Agriculture / Agronomy portal |

Slash-and-burn is an agricultural technique that involves the cutting and burning of plants in forests or woodlands to create fields. It is subsistence agriculture that typically uses little technology. It is typically key in shifting cultivation agriculture, and in transhumance livestock herding.[1]

Old terms for slash-and-burn in English include assarting, swidden, and fire-fallow cultivation. Today the term slash-and-burn is mainly associated with tropical rain forests. Slash-and-burn is used by between 200 and 500 million people worldwide.[2][3] In 2004 it was estimated that, in Brazil alone, 500,000 small farmers cleared an average of one hectare of forest per year each. The technique is not sustainable in large populations, because without the trees, the soil quality becomes too low to support crops. The farmers would have to move on to virgin forest and repeat the process. Methods such as Inga alley farming have been proposed as alternatives to this ecological destruction.[4]

35% of the farming land in the Murray Darling Basin area was cleared using 'Slash and Burn.'

History

Historically, slash-and-burn cultivation has been practiced throughout much of the world, in grasslands as well as woodlands.

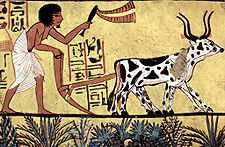

During the Neolithic Revolution, which included agricultural advancements, groups of hunter-gatherers domesticated various plants and animals, permitting them to settle down and practice agriculture, which provides more nutrition per hectare than hunting and gathering. This happened in the river valleys of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Due to this decrease in food from hunting, as human populations increased, agriculture became more important. Some groups could easily plant their crops in open fields along river valleys, but others had forests blocking their farming land.

In this context, humans used slash-and-burn agriculture to clear more land to make it suitable for plants and animals. Thus, since Neolithic times, slash-and-burn techniques have been widely used for converting forests into crop fields and pasture.[5] Fire was used before the Neolithic as well, and by hunter-gatherers up to present times. Clearings created by fire were made for many reasons, such as to draw game animals and to promote certain kinds of edible plants such as berries.

Slash-and-burn fields are typically used and "owned" by a family until the soil is exhausted. At this point the "ownership" rights are abandoned, the family clears a new field, and trees and shrubs are permitted to grow on the former field. After a few decades, another family or clan may then use the land and claim usufructuary rights. In such a system there is typically no market in farmland, so land is not bought or sold in the open market and land rights are "traditional." In slash-and-burn agriculture, forests are typically cut months before a dry season. The "slash" is permitted to dry, and then burned in the following dry season. The resulting ash fertilizes the soil and the burned field is then planted at the beginning of the next rainy season with crops such as upland rice, maize, cassava, or other staples. Most of this work is typically done by hand, using such basic tools as machetes, axes, hoes, and makeshift shovels.

Large families or clans wandering in the lush woodlands long continued to be the most common form of life through human history. Axes to fell trees and sickles for harvesting grain were the only tools people might bring with them. All other tools were made from materials they found at the site, such as fire stakes of birch, long rods (vanko), and harrows made of spruce tops. The extended family conquered the lush virgin forest, burned and cultivated their carefully selected swidden plots, sowed one or more crops, and then proceeded on to forests that had been noted in their wanderings. In the temperate zone the forest regenerated in the course of a lifetime. So swidden was repeated several times in the same area over the years. But in the tropics the forest floor gradually depleted. It was not only in the moors, as in Northern Europe, but also in the steppe, savannah, prairie, pampas and barren desert in tropical areas where shifting cultivation is the oldest type of farming (Clark 1952 91-107).[6]

Historical references

In Southern Europe Mediterranean climates, originally forested from times immemorial, there were open evergreen deciduous and pine forests. After slash and burn agriculture practice began this type of forest had less capacity for regeneration than the forest north of the Alps.

In Northern Europe, there was usually only one crop harvested before grass growth took over, while in the south, suitable fall was used for several years and the soil was quickly exhausted. Slash and burn shifting cultivation therefore ceased much earlier in the south than the north. Most of the forests in the Mediterranean region had disappeared by classical times. The classical authors wrote about the great forests (Semple 1931 261-296).[7]

Homer writes of wooded Samothrace, Zacynthos, Sicily and other wooded land.[8] The authors give us the general impression that the Mediterranean countries had more forest than now, but that it had already lost much forest, and that it was left there in the mountains (Darby 1956 186).[9]

It is clear that Europe remained wooded, and not only in the north. However, during the Roman Iron Age and early Viking Age, forest areas drastically reduced in Northern Europe, and settlements were regularly moved. There is no good explanation for this mobility, and the transition to stable settlements from the late Viking period, as well as the transition from shifting cultivation to stationary use of arable land. At the same time plows appears as a new group of implements were found both in graves and in depots. It can be confirmed that early agricultural people preferred forest of good quality in the hillside with good drainage, and traces of cattle quarters are evident here.

The Migration Period in Europe after the Roman Empire and immediately before the Viking Age suggests that it was still more profitable for the peoples of Central Europe to move on to new forests after the best parcels were exhausted than to wait for the new forest to grow up. Therefore, the peoples of the temperate zone in Europe slash and burners, remained for as long as the forests permitted.

This exploitation of forests explains this rapid and elaborate move. The forest could not tolerate this in the long run; it first ended in the Mediterranean. The forest here did not have the same vitality as the powerful coniferous forest in Central Europe. Deforestation was partly caused by burning for pasture fields. Missing timber delivery led to higher prices and more stone constructions in the Roman Empire (Stewart 1956 123).[10]

The forest also decreased gradually northwards in Europe, but in the Nordic countries it has survived. The clans in pre-Roman Italy seemed to be living in temporary locations rather than established cities. They cultivated small patches of land, guarded their sheep and their cattle, traded with foreign merchants, and at times fought with one another: etruscans, umbriere, ligurianere, sabinere, Latinos, campaniere, apulianere, faliscanere, and samniter, just to mention a few. These Italic ethnic groups developed identities as settlers and warriors ca. 900 BC. They built forts in the mountains, today a subject of much investigation. The forest has hidden them for a long time, but eventually they will provide information about the people who built and used these buildings. The ruin of a large samnittisk temple and theater at Pietrabbondante is under investigation. These cultural relics have slumbered in the shadow of the glorious history of the Roman Empire.

The Greek explorer and merchant Pytheas of Marseilles made a voyage to Northern Europe ca. 330 BC. Part of his itinerary is kept at Polybios, Pliny and Strabo. Pytheas had visited Thule, which lay a six-day voyage north of Britain.

There "the barbarians showed us the place where the sun does not go to sleep. It happened because there the night was very short -- in some places two, in others three hours -- so that the sun shortly after its fall soon went up again." He says that Thule was a fertile land, "rich in fruits that were ripe only until late in the year, and the people there used to prepare a drink of honey. And they threshed the grain in large houses, because of the cloudy weather and frequent rain. In the spring they drove the cattle up into the mountain pastures and stayed there all summer." This description may fit well on the West-Norwegian conditions. Here is an instance of both dairy farming and drying/threshing in a building.

In Italy, shifting cultivation was a thing of the past at the birth of Christ. Tacitus describes it as the strange cultivation methods he had experienced among the Germans, whom he knew well from his stay with them. Rome was entirely dependent on shifting cultivation by the barbarians to survive and maintain "Pax Romana", but when the supply from the colonies "trans alpina" failed, the Roman Empire collapsed.

Tacitus writes in 98 AD about the Germans: fields are proportionate to the participating growers, but they share their crops with each other by reputation. Distribution is easy because there is great access to land. They change soil every year, and mark some off to spare, for they seek not a strenuous job in cramming this fertile and vast land even greater ydelser, by planting apple orchards, cultivated spesial beds or watering gardens; grain is the only thing they insist that the ground will provide. The original text reads,[11] "agri pro numero cultorum ad universis vicinis occupantur, quos mox inter se secundum dignationem partientur, facilitate partiendi camporum spatial praestant, arva per annos mutant, et superest ager, nec enim cum ubertate et amplitudine soli labore contendunt, ut pomaria conserant et prata separent et hortos rigent, sola terrae seges imperatur." Tacitus discusses the shifting cultivation.[12][13]

Strabo (63 BC - about 20 AD) also writes about sveberne in Geographicon VII, 1, 3. Common to all the people in this area is that they can easily change residence because of their sordid way of life; that they do not grow any fields and do not collect property, but live in temporary huts. They get their nourishment from their livestock for the most part, and like nomads, they pack all their goods in wagons and go on to wherever they want. Horazius writes in 17 BC (Carmen säculare, 3, 24, 9 ff .) about the people of Macedonia. The proud Getae also live happily, growing free food and cereal for themselves on land that they do not want to cultivate for more than a year, "vivunt et rigidi Getae, immetata quibus iugera liberal fruges et Cererem freunt, nec cultura placet longior annua." Several classical writers have descriptions of shifting cultivation people. Many peoples’ various shifting cultivations characterized the migration Period in Europe. The exploitation of forests demanded constant displacement, and large areas were deforested.

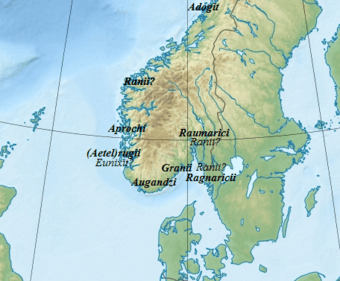

Locations of the tribes described by Jordanes in Norway, contemporary with, and some possibly ruled by Rodulf. Jordanes was of Gothic descent and ended up as a monk in Italy. In his work De origine actibusque Getarum (The Origin and Deeds of the Getae/Goths[14]),[15] the Gothic origins and achievements, the author of 550 AD provides information on the big island Scandza, which the Goths come from. He expects that of the tribes who live here, some are adogit living far north with 40 days of the midnight sun. After adogit come screrefennae and suehans who also live in the north. Screrefennae moved a lot and did not bring to the field crops, but made their living by hunting and collecting bird eggs. Suehans was a seminomadic tribe that had good horses like Thüringians and ran fur hunting to sell the skins. It was too far north to grow grain. Prokopios, ca. 550 AD, also describes a primitive hunter people he calls skrithifinoi. These pitiful creatures had neither wine nor corn, for they did not grow any crops. "Both men and women engaged incessantly just in hunting the rich forests and mountains, which gave them an endless supply of game and wild animals." Screrefennae and skrithifinoi is well Sami who often have names such as; skridfinner, which is probably a later form, derived from skrithibinoi or some similar spelling. The two old terms, screrefennae and skrithifinoi, are probably origins in the sense of neither ski nor finn. Furthermore, in Jordanes' ethnographic description of Scandza are several tribes, and among these are finnaithae "who was always ready for battle" Mixi evagre and otingis that should have lived like wild beasts in mountain caves, "further from them" lived osthrogoth, raumariciae, ragnaricii, finnie, vinoviloth and suetidi that would last prouder than other people.

The instance of fire in North East Sweden changed as the agriculture changed. Historically the Sami people did not burn the land as it destroyed the lichen required by their reindeer. The new farmers frequently used slash and burn farming. During the nineteenth century the Swedish timber industry moved north where they would clear the land of trees but leave the waste as fire risk behind. Fires around the 1870s were frequent.[16] There was a fire in Norrland in 1851 and then every ten years in 1868, 1878 and teo towns were lost in 1888.[17]

Cultures

Modern Western world

Slash-and-burn could be distinctly defined as the large-scale deforestation of acres of forests for agricultural usage. The ashes that come from the trees would also help farmers, for it provides nutrients for farming.[18]

In regions which industrialized, including Europe and North America, the practice was abandoned over the past few centuries as market agriculture was introduced, and land came to be owned. For example, slash-and-burn agriculture was initially practiced by European pioneers in North America like Daniel Boone and his family who cleared land in the Appalachian Mountains in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries.[19] However, the land of such slash-and-burn farmers was eventually taken over by modern systems of land tenure which focus on the long-term improvement of farmland, and discourage the older subsistence practices associated with slash-and-burn agriculture.

Preserving the northern European heritage

Telkkämäki Nature Reserve (Kaavi, Finland) is a heritage farm portraying the old slash-and-burn heritage. At Telkkämäki farm, the visitor can see how people lived and farmed in the past, when the slash-and-burn agriculture was practiced in the North Savonian region in Eastern Finland from the 15th century. Some areas of Telkkämäki Nature Reserve are burnt annually.[20] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0S7LTbJ-ErQ

South Asia

Tribal groups in the northeastern states of India like Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland, and also in the districts of Bangladesh like Rangamati, Khagrachari, Bandarban and Sylhet refer to slash and burn agriculture as "Jhum" or "Jhoom cultivation". This system involves clearing a piece of land by setting fire or clear felling and using the area for growing crops of agricultural importance such as upland rice, vegetables or fruits. After a few cycles, the land loses fertility and a new area is chosen. Jhum cultivation is most practiced on the slopes of hills in thickly forested landscapes. The cultivators cut the treetops to allow sunlight to reach the land. They burn all the trees and grasses for clean and fresh soil. It is believed that this helps to fertilize the land, but can leave it vulnerable to erosion. Later they make a hole with a heavy wood or local chopper in chakma Tāgala after that seeds of different crops[21] like local/traditional sticky rice,maize,eggplant,cucumber etc. are planted. Plants on the slopes survive the rainy season floods. Looking at all the effects, the government of Mizoram has launched a policy to end Jhum cultivation in the state.[22]

Slash-and-burn is typically a type of subsistence agriculture, and not focused by the need to sell crops in world markets. Rather, planting decisions are made in the context of needs of the family or clan for the coming year. [23]

Ecological implications

| |||||

Although a solution for overpopulated tropical countries where subsistence agriculture may be the traditional method of sustaining many families, the consequences of slash-and-burn techniques for ecosystems are almost always destructive.[24] This happens particularly as population densities increase, and as a result farming becomes more intensively practiced. This is because as demand for more land increases, the fallow period by necessity declines. The principal vulnerability is the nutrient-poor soil, pervasive in most tropical forests. When biomass is extracted even for one harvest of wood or charcoal, the residual soil value is heavily diminished for further growth of any type of vegetation. Sometimes there are several cycles of slash-and-burn within a few years time span; for example in eastern Madagascar the following scenario occurs commonly. The first wave might be cutting of all trees for wood use. A few years later, saplings are harvested to make charcoal, and within the next year the plot is burned to create a quick flush of nutrients for grass to feed the family zebu cattle. If adjacent plots are treated in a similar fashion, large-scale erosion will usually ensue, since there are no roots or temporary water storage in nearby canopies to arrest the surface runoff. Thus, any small remaining amounts of nutrients are washed away. The area is an example of desertification, and no further growth of any type may arise for generations.

The ecological ramifications of the above scenario are further magnified, because tropical forests are habitats for extremely biologically diverse ecosystems, typically containing large numbers of endemic and endangered species. Therefore, the role of slash-and-burn is significant in the current Holocene extinction.

Slash-and-char is an alternative that alleviates some of the negative ecological implications of traditional slash-and-burn techniques.

See also

- 1997 Indonesian forest fires

- 2006 Southeast Asian haze

- 2013 Southeast Asian haze

- Oil palm plantations

- Satoyama

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0S7LTbJ-ErQ

- http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Slash_and_burn

References

- ↑ Tony Waters, The Persistence of Subsistence Agriculture, p. 3. Lexington Books (2007).

- ↑ Slash and burn, Encyclopedia of Earth

- ↑ Skegg, Martin.True Stories: Up In Smoke The Guardian 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Elkan, Daniel. Slash-and-burn farming has become a major threat to the world's rainforest The Guardian 21 April 2004

- ↑ Jaime Awe, Maya Cities and Sacred Caves, Cu bola Books (2006)

- ↑ Clark J.G.D. 1952, Farming: Clearance and Cultivation II Prehistoric Europe: The Economic Basis, Cambridge.

- ↑ Semple E.C.1931, Ancient Mediterranean Forests and the Lumber Trade II Henry Holt et al., The Geography of the Mediterranean region, New York.

- ↑ Homer Iliad, XIII, XIV ---- 0.1 to 2.

- ↑ Darby H.C. 1950, Domesday Woodland II Economic History Review, 2d ser.,III, London. 1956, The clearing of the Woodland in Europe II

- ↑ Stewart O.C. 1956, Fire as the First Great Force Employde by Man II Thomas W.L. Man's role in changing the face of the earth, Chicago.

- ↑ Perkins and Marvin, Ex Editione Oberliniana, Harvard College Library, 1840 (Xxvi, 15-23).

- ↑ A W Liljenstrand wrote 1857 in his doctoral dissertation, "About changing of soil" (p. 5 ff.), That Tacitus discusses the shifting cultivation: "arva per annos mutant".

- ↑ Arenander E.O. 1923, Germanemas jordbrukskultur ornkring KristifØdelse // Berattelse over Det Nordiska Arkeologmotet i Stockholm 1922, Stockholm.

- ↑ Late antique writers commonly used Getae for Goths mixing the peoples in the process.

- ↑ G. Costa, 32. Also: De Rebus Geticis: O. Seyffert, 329; De Getarum (Gothorum) Origine et Rebus Gestis: W. Smith, vol 2 page 607

- ↑ Alexander, Andrew C. Scott, David M.J.S. Bowman, William J. Bond, Stephen J. Pyne, Martin E. (2013). Fire on earth : an introduction. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc. p. 287. ISBN 1118570715.

- ↑ Pyne, Stephen J. (1997). World fire : the culture of fire on earth (Pbk. ed. ed.). Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 85. ISBN 0295975938.

- ↑ "Slash and Burn Agriculture - An Overview of Slash and Burn". Geography.about.com. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- ↑ "Blog Archive » Farmer Power: The Continuing Confrontation between Subsistence Farmers and Development Bureaucrats". Ethnography.com. 2010-12-02. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- ↑ "Telkkämäki Nature Reserve". Outdoors.fi. 2013-05-14. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- ↑ http://www.banglapedia.org/HT/J_0120.htm

- ↑ TI Trade (2011-01-17). "The Assam Tribune Online". Assamtribune.com. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- ↑ Tony Waters, The Persistence of Subsistence Agriculture." Lexington Books (2007), p. 48.

- ↑ http://library.thinkquest.org/26252/evaluate/11.htm

Further reading

- Karki, Sameer (2002). "Community Involvement in and Management of Forest Fires in South East Asia" (PDF). Project FireFight South East Asia. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)