Sir Thomas More (play)

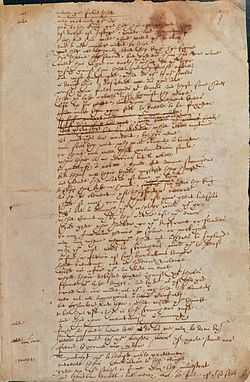

Sir Thomas More is a collaborative Elizabethan play, generally thought to be written by Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle and revised by several other writers including William Shakespeare. It depicts the life and death of the Catholic martyr Thomas More. It survives only in a single manuscript, now owned by the British Library. The manuscript is notable because three pages of it are considered to be in the hand of Shakespeare, who is the only possible Catholic among the authors, and for the light it sheds on the collaborative nature of Elizabethan drama and the theatrical censorship of the era.

In 1871, Richard Simpson proposed that some additions to the play had been written by Shakespeare, and a year later James Spedding, editor of the works of Sir Francis Bacon, while rejecting some of Simpson's suggestions, supported the attribution to Shakespeare of the passage credited to Hand D.[1] In 1916, the paleographer Sir Edward Maunde Thompson published a minute analysis of the handwriting of the addition and judged it to be Shakespeare's. The case was strengthened with the publication of Shakespeare's Hand in the Play of Sir Thomas More (1923) by five noted scholars who analysed the play from multiple perspectives, all of which led to the same affirmative conclusion. Although some dissenters remain, the attribution has been generally accepted since the mid-20th century and most authoritative editions of Shakespeare's works, including The Oxford Shakespeare, include the play. It was performed with Shakespeare's name included amongst the authors by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2005.

Characters

Sir Thomas More has an unusually high total of 59 speaking parts, including 22 in the first 500 lines of the play; this, plus crowd scenes, would have taxed the ability of any playing company of the time to stage it. The job could only be managed through complex doubling and more-than-doubling of roles by the actors. Out of necessity, the play is structured to allow for this multiple doubling of roles: it is set up in three phases—More's rise; More's Chancellorship; More's fall—with very limited overlap between the thirds. Only three characters, More himself and the Earls of Shrewsbury and Surrey, appear in all three portions; six other characters—Lady More, Palmer, Roper, Sergeant Downes, the Lord Mayor, and a sheriff—appear in two of the three segments.

- Thomas More – undersheriff of London; later Sir Thomas More and Lord Chancellor

In London

- Earl of Shrewsbury

- Earl of Surrey – characterised as Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, but historically the events depicted involved his father, Thomas, Duke of Norfolk

- John Lincoln – broker (the only executed rioter named in Holinshed's Chronicles)[2]

- Williamson – carpenter (a conflation of two citizens mentioned in Holinshed)[3]

- Doll – Williamson's wife

- George Betts – rioter

- Clown Betts – Ralph, his brother (Holinshed mentions two brothers named "Bets" who were sentenced to death but pardoned)[4]

- Sherwin – goldsmith (mentioned in Holinshed as sentenced to death but pardoned)[5]

- Francis de Barde – a Lombard (Lombard banking was common in London)[6]

- Cavaler – a Lombard or a Frenchman, associated with de Barde

- Lord Mayor of London – historically John Rest

- Justice Suresby – magistrate

- Lifter – cutpurse

- Smart – plaintiff against Lifter (non-speaking role)

- Recorder

In Court

- Sir Thomas Palmer – soldier and friend to King Henry VIII

- Sir Roger Chomley – historically the Lieutenant of the Tower, but portrayed in the play as a member of the Council

- Sir John Munday – an alderman

- Downes – Sergeant-at-Arms to the King who is injured in the riots

- Crofts – messenger

- Randall – More's servant

- Morris – secretary to the Bishop of Winchester

- Jack Falconer – Morris' servant

- Erasmus – Renaissance humanist and Catholic priest

Lord Cardinal's Players

- Inclination

- Prologue

- Wit

- Lady Vanity

- Luggins

More's Party

- Lady More – More's wife; historically Alice Middleton

- William Roper – More's son-in-law

- Roper's wife – More's daughter

- More's other daughter – either Elizabeth (b. 1506), Cicely (b. 1507), or his stepdaughter, Alice[7]

- Lady More – More's second wife, Alice

- Catesby – More's steward

- Gough – More's secretary

- Dr. Fisher, Bishop of Rochester

Others

- Lieutenant of the Tower of London

- Gentleman Porter of the Tower

- Three Warders of the Tower

- Hangman

- A poor woman – a client of More

- More's Servants – Ned Butler, Robin Brewer, Giles Porter, and Ralph Horse-Keeper

- Two Sheriffs

- Messengers

- Clerk of the Council

- Officers, Justices, Rioters, Citizens, City Guard, Attendants, Serving-men, Lords, Ladies, Aldermen, Lords of the Council, Prentices[8]

Synopsis

The play dramatises events in More's life, both real and legendary, in an episodic manner in 17 scenes, four of them cancelled,[9] unified only by the rise and fall of More's fortunes. It begins with the Ill May Day events of 1517, in which More, as undersheriff of London, quells riots directed at immigrants living in London. (On Tylney's orders, the "foreigners" of the original draft were changed to "Lombards"—presumably because there were few Lombards in London to take offence at the reference). In these scenes, More is made to express a doctrine of passive submission to civil authority which, while hardly appropriate to his fame, is pure late-Tudor orthodoxy.

The middle scenes of the play depict More as chancellor, and they are a medley of episodes taken from William Roper's biography and Foxe's Book of Martyrs. More is shown embarrassing a self-important judge, playing a practical joke on Erasmus, and encouraging an unkempt servant to cut his hair (Foxe ascribes the last episode to Thomas Cromwell.) The only unity in these scenes is that of character: each serves to illustrate More's wit and good sense.

The last group of scenes treats More's decline and death. Unsurprisingly for a play written when a Tudor still reigned, the king who has More executed is treated gingerly: the grounds of their dispute are not mentioned, and no one, including More, voices any direct criticism of the monarch. Instead, his fate is ascribed in the medieval manner to the inevitable turning of Fortune's wheel, and More himself accepts death with stoic resignation. In all, the authors seem to have gone to great lengths to make a play on this subject acceptable to a Tudor monarch; still, one can hardly be surprised that they failed.

The manuscript

Now MS. Harley 7368 in the collection of the British Library, the manuscript's provenance can be traced back to 1728, when it belonged to a London book collector named John Murray. He donated it to the collection of Edward Harley, 3rd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, who bequeathed it to the British Museum with the rest of his manuscript collection in 1753. Some time between 1728 and 1753 the play was bound with another manuscript, The Humorous Lovers.[10]

Now in poor condition, the original manuscript probably consisted of 16 leaves—31 handwritten pages of a working draft of the play (foul papers), with the last page blank. Two or three of the original leaves have been torn out, and seven leaves and two smaller pieces of paper have been inserted.

Aside from folios 1 and 2, the wrapper of the manuscript proper, the revised extant manuscript comprises the following:

1) Folios 3–5, Hand S: the first three scenes of the play, through page 5a; censored by Edmund Tylney, the Master of the Revels, but otherwise intact. On page 5b, all text after the first 16 lines is marked for deletion. At least one, and probably two, of the leaves immediately following (the original leaves 6 and 7) are missing.

2) Folio 6, Addition I, Hand A: a single leaf, written on only one side. The addition is misplaced, and belongs later in the play, with page 19a.

3) Folios 7–9, Addition II: three leaves replacing the excised material on 5b and the original 6 and probable 7. Each of the three leaves is in a different hand.

- Folio 7a, Addition IIa, Hand B: a scene to replace a short deleted scene on 5b.

- Folio 7b, Addition IIb, Hand C: another complete scene, with stage directions leading to its successor.

- Folios 8–9, Addition IIc, Hand D: a three-page scene (page 9b being blank), with about a dozen corrections in Hand C.

4) Folios 10–11, Hand S: back to the original manuscript, though with some insertions on pages 10a and 11a in Hand B.

5) Folio 11c, Addition III, Hand C: the first of the two insertions on smaller pieces of paper, formerly pasted over the bottom of page 11b, and consisting of a single 21-line soliloquy meant to begin the next scene.

6) Folios 12–13, Addition IV, Hands C and E: four pages to replace excised or cancelled material, written mainly in Hand C but with input from Hand E on page 13b.

7) Folio 14a Hand S: the original again, and the whole page cancelled for deletion. Addition IV, directly previous, replaces this material.

8) Folio 14c, Addition V, Hand C: the second of the insertions on smaller sheets of paper, formerly pasted over the bottom of page 14a.

9) Folios 14b and 15, Hand S: the original again.

10) Folio 16, Addition VI, Hand B: the last of the six Additions.

11) Folios 17-22a, Hand S: the conclusion of the play in the original version. On page 19a a long passage is cut, and this is the place where the mislocated Addition I, folio 6, actually belongs.[11]

Hand C attempted to provide corrections to the whole, enhancing its coherence; yet some stage directions and speech prefixes are missing, and the stage directions that exist are sometimes incorrect. (In Additions III and IV, More speaks his soliloquy before he enters.)

Scholars, critics, and editors have described the text as "chaotic" and "reduced to incoherence", but in 1987 Scott McMillin maintained that the play could be acted as is;[12] and at least one production of the play has ensued, by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2005.

The manuscript was first printed and published in 1844, two and a half centuries after it was written, by the Shakespeare Society, edited by Alexander Dyce; and again in 1911 by the Malone Society, edited by W. W. Greg.

Part of the need for revisions of the play was clearly due to purely practical concerns of stagecraft, apart from the demands of political censorship. Much of the point of the revision was to streamline the play, to make it more actable; though even the revised version would have needed a minimum cast of 18—13 adults and five boys.[13] Two of the Additions, III and VI, occur at the beginning and end of the middle third respectively, giving more time for costume changes. Addition III provides a soliloquy by More and a 45-line dialogue between two actors; Addition VI provides a similar breathing-space for the actors to get ready for the play's final phase.[14]

Allowing for a range of uncertainties, it is most likely true that the original text of Sir Thomas More was written ca. 1591-3, with a special focus on 1592-3 when the subject of hostility against "aliens" was topical in London. Edmund Tylney censored the play when it was submitted to him for approval at that time, for this topicality as well as for more general considerations of controlling political expression on the stage. The effort at revision is difficult to date; many scholars have favoured ca. 1596, though a date as late as ca. 1604 is also possible.

Authorship

The manuscript is a complicated text containing many layers of collaborative writing, revision, and censorship. Scholars of the play think that it was originally written by playwrights Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle and some years later heavily revised by another team of playwrights, including Thomas Heywood, Thomas Dekker, and William Shakespeare.

The most common identifications for the six hands:

- HAND S – Anthony Munday, the original manuscript;

- HAND A – Henry Chettle;

- HAND B – Thomas Heywood;

- HAND C – A professional scribe who copied out a large section of the play;

- HAND D – William Shakespeare;

- HAND E – Thomas Dekker.

Munday, Chettle, Dekker, and Heywood wrote for the Admiral's Men during the years before and after 1600, which may strengthen the idea of a connection between the play and that company. Shakespeare, in this context, seems the odd man out. In his study of the play, Scott McMillin entertains the possibility that Shakespeare's contribution might have been part of the original text from the early 1590s, when Shakespeare may have written for the Lord Strange's Men.[15]

Evidence for Shakespeare's contribution

The suggestion that passages in Hand D were by Shakespeare was first made in 1871 by Richard Simpson.[16] It was supported and disputed over a long period on the evidence of literary style and Shakespeare's distinctive handwriting. The lines in Hand D "are now generally accepted as the work of Shakespeare."[17] If the Shakespearean identification is correct, these three pages represent the only surviving examples of Shakespeare's handwriting, aside from a few signatures on documents. The manuscript, with its numerous corrections, deletions and insertions, enables us to glimpse Shakespeare in the process of composition.[18]

The evidence for identifying Shakespeare as Hand D is of various types:

- Handwriting similar to the six existing signatures of Shakespeare;

- Spellings characteristic of Shakespeare;

- Stylistic elements similar to Shakespeare's acknowledged works.

The original perceptions of Simpson and Spedding in 1871-2 were based on literary style and content and political outlook, rather than palaeographic and orthographic considerations. Consider one example of what attracted attention to the style of Hand D.

First, from Sir Thomas More, Addition IIc, 84-7:

- For other ruffians, as their fancies wrought,

- With self same hand, self reasons, and self right,

- Would shark on you, and men like ravenous fishes

- Would feed on one another.

Next, from Coriolanus, I,i,184-8:

- What's the matter,

- That in these several places of the city

- You cry against the noble Senate, who

- (Under the gods) keep you in awe, which else

- Would feed on one another?

Thirdly, Troilus and Cressida, I,iii,121-4:

- And appetite, an universal wolf

- (So doubly seconded with will and power)

- Must make perforce an universal prey,

- And last eat up himself.[19]

Finally, Pericles, Prince of Tyre, II,i,26–32:

- 3rd Fisherman:...Master, I marvel how the fishes live in the sea.

- 1st Fisherman: Why, as men do a-land; the great ones eat up

- the little ones. I can compare our rich misers to nothing so fitly

- as to a whale: 'a plays and tumbles, driving the poor fry before him,

- and at last devour them all at a mouthful.

Many features like this in the Hand D addition to Sir Thomas More first attracted the attention of Shakespeare scholars and readers, and led to more intensive study from a range of specialised perspectives.

Audience perception

Subjectively, audiences experience More's speech in the passage attributed to Shakespeare as more vividly written and dramatically effective than the rest of the work. While Shakespeare's supposed contribution is consistent with the overall theme and develops the plot, there is an impression of a virtuoso piece inserted, but not completely integrated, into the play.[20] Some editors go as far as to question whether Shakespeare had read any of the other contributions at all.[21]

Performance history

The play was most likely written to be acted by Lord Strange's Men, the only company of the time that could have mounted such a large and demanding production, at Philip Henslowe's Rose Theatre, which possessed the special staging requirements (large-capacity second-level platform and special enclosure) called for by the play.[22] The massive lead role of More, 800-plus lines, was designed for Edward Alleyn, the only actor up to that time who is known to have played such large-scale roles. After the re-organization of the playing companies in 1594, the manuscript may well have passed into the possession of the Admiral's Men.

Whether the play was ever produced in the Elizabethan/Jacobean age is not known, but it is obvious by the nature of the revisions and the mention of the actor Thomas Goodale in 3.1 that it was written for the public stage.[23] Since that time no recorded performance of Sir Thomas More took place until a three-night student production by the Birkbeck College, University of London, in December 1922. The play was staged with more than 40 students at the King's School, Canterbury, 4–6 November 1938, with P. D. V. Strallen in the title role. The first known professional staging of the play was 22–29 June 1954 at the London Theatre Centre for the Advance Players Association. It was first performed in Elizabethan costumes and then in modern dress, with Michael Beint as More.[24]

Sir Thomas More has been acted in whole or in part several times as a radio play, twice by BBC Third Programme (1948, 1956), by the Austrian public radio ORF in 1960, and then again by BBC Radio 3 in 1983 with Ian McKellen playing the title role.[25] McKellen also played the role at the Nottingham Playhouse 10 June-4 July 1964, taking over from John Neville on short notice, when the latter had artistic differences with director Frank Dunlop during rehearsals.[26]

The play has been infrequently revived since, Nigel Cooke playing More for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2005.

See also

- A Man for All Seasons – a modern play about Sir Thomas More

Notes

- ↑ Jowett 2011, p. 437

- ↑ Jowett 2011, pp. 134, 474–5, 479.

- ↑ Jowett 2011, pp. 134, 473–4.

- ↑ Jowett 2011, pp. 134, 479.

- ↑ Jowett 2011, pp. 134, 479.

- ↑ Jowett 2011, pp. 135.

- ↑ Jowett 2011, pp. 136.

- ↑ Greg 1990, pp. xxx – xxxi; Jowett 2011, pp. 132–7.

- ↑ Greg 1990, pp. xxvi–xxvii

- ↑ Jowett 2011, p. 345

- ↑ Bald 1949, pp. 47–52, McMillin 1987, pp. 13–33.

- ↑ McMillin 1987, p. 42

- ↑ McMillin 1987, pp. 74–94.

- ↑ McMillin 1987, pp. 44–9.

- ↑ McMillin 1987, pp. 135–59.

- ↑ Thompson 1916, p. 39.

- ↑ Evans 1997, p. 1775; Woodhuysen 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Bate 2008, p. 334.

- ↑ Halliday 1964, p. 457.

- ↑ Jowett 2011, pp. 18–22: "Compared with the rest of the play, the passage is exceptionally dynamic, poetically resonant and vividly etched. Even audience members who are unaware of the authorship issue often find that the play speaks with more urgency here."

- ↑ Wells 2010, pp. 813

- ↑ McMillin 1987, pp. 464–73, 113–34.

- ↑ Jowett 2011, p. 96; Gabrieli & Melchiori 1990, p. 32.

- ↑ Gabrieli & Melchiori 1990, pp. 33–4; Jowett 2011, p. 108.

- ↑ Jowett 2011, pp. 108–9.

- ↑ McKellen.

References

- Bald, R. C. (1949). "The Booke of Sir Thomas More and Its Problems". Shakespeare Survey (Cambridge University Press) 2: 44–65. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- Bate, Jonathan (2008). "Justice". Soul of the Age: the Life, Mind and World of William Shakespeare. Viking Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-91482-1.

- Evans, G[wynne] Blakemore (1997) [1974]. "Introduction to Sir Thomas More: The Additions Ascribed to Shakespeare". In Evans, G. Blakemore; Tobin, J. J. M. The Riverside Shakespeare. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 1775–7. ISBN 978-0-395-75490-0.

- Greg, W[alter] W[illiam], ed. (1990) [First published 1911]. Sir Thomas More. Malone Society Reprint. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-729016-7. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- Gurr, Andrew (1996). The Shakespearian Playing Companies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-812977-7.

- Halliday, F. E. (1964). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Penguin.

- Hays, Michael L. "Shakespeare’s Hand in Sir Thomas More: Some Aspects of the Paleographic Argument.". Shakespeare Studies VIII (1975): 241-53; also <whiteknightpubs.org> and <academia.edu>.

- Howard-Hill, T. H., ed. (2009) [1989]. Shakespeare and Sir Thomas More: Essays on the Play and its Shakespearian Interest. Cambridge University Press.

- Jowett, John, ed. (2011). Sir Thomas More. Arden Shakespeare. Methuen Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904271-47-5.

- McKellen, Ian. "Sir Thomas More". Ian McKellen Stage. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- McMillin, Scott, ed. (1987). The Elizabethan Theatre and the "Book of Sir Thomas More". Cornell University Press.

- Pollard, Alfred W., ed. (1923). Shakespeare's Hand in the Play of Sir Thomas More. Cambridge University Press.

- Thompson, Edward Maunde (1916). Shakespeare's Handwriting: A Study. Oxford University Press.

- Vittorio, Gabrieli; Melchiori, Giorgio, eds. (1999). Sir Thomas More. Manchester University Press.

- Wells, Stanley, ed. (2010). The New Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare (2 ed.). Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88632-1.

- Woodhuysen, H. R. (2010). "Shakespeare's writing, from manuscript to print". In Grazia, Margreta; Wells, Stanley. The New Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–44. ISBN 978-0-521-88632-1. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

External links

- Greg, W. W. ed. The Book of Sir Thomas More. Malone Society Reprint. Oxford UP, 1911.

- Sir Thomas More eText at Project Gutenberg

- Hays, Michael L. . “Shakespeare’s Hand in Sir Thomas More: Some Aspects of the Paleographic Argument.” Shakespeare Studies VIII (1975): 241-53.

- Pollard, Alfred W., ed. Shakespeare's hand in the play of Sir Thomas More. Cambridge University Press, 1923.

.png)