Sir Philip II Courtenay

| Sir Philip II Courtenay of Powderham | |

|---|---|

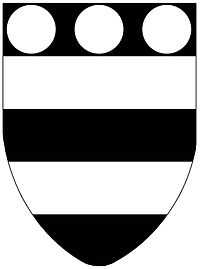

Arms of Sir Philip II Courtenay: Courtenay impaling Hungerford with supporters two Courtenay boars. In the spandrels are the heraldic badges of Hungerford: three conjoined sickles and the Peverell garbs. Detail from Bishop Peter Courtenay's Mantelpiece, erected by Sir Philip's son Bishop Peter Courtenay (d.1492), Bishop's Palace, Exeter.[1] | |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Hungerford |

|

Issue

Sir William Courtenay Sir Philip Courtenay Peter Courtenay Sir Walter Courtenay Edmund Courtenay Humphrey Courtenay Sir John Courtenay Anne Courtenay Elizabeth Courtenay Philippe Courtenay Katherine Courtenay | |

| Noble family | Courtenay |

| Father | Sir John Courtenay |

| Mother | Joan Champernoun |

| Born | 18 January 1404 |

| Died | 16 December 1463 (aged 59) |

Sir Philip II Courtenay (18 January 1404 – 16 December 1463) of Powderham,[lower-alpha 1] Devon, was the senior member of a junior branch of the powerful Courtenay family, Earls of Devon.

Origins

Sir Philip II Courtenay was born on 18 January 1404, the eldest son and heir of Sir John Courtenay (died before 1415) of Powderham, by his wife Joan[2] Champernoun (died 1419),[3] widow and 4th wife of Sir James Chudleigh[4] and daughter of Alexander[5] Champernoun (d.1441) of Beer Ferrers,[6] Devon, by Joan Ferrers, daughter and co-heiress of Martin Ferrers[6] of Bere Ferrers.

He was the grandson of Sir Philip Courtenay I and therefore the great-grandson of Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (d.1377) and Margaret de Bohun (d.1391). He had a brother, Sir Humphrey Courtenay, who died without issue.[7] Philip was heir to his uncle, Richard Courtenay (d.1415), Bishop of Norwich[8] and also to his other uncle Sir William Courtenay (d.1419)[7]

Seat

Courtenay's seat was Powderham Castle, given to his grandfather Sir Philip I Courtenay (1340-1406), of Powderham, (a younger son of Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (d.1377)), by his mother Margaret Bohun, whose father had given it to her as her marriage portion.

Battle of Clyst Heath (1455)

He had been badly treated by his distant cousin Thomas de Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon (1414–1458), whose seat was at Tiverton Castle, and during the turbulent and lawless era of the Wars of the Roses, he supported the challenge against the earl, for local supremacy in Devon, put up by the Lancastrian courtier, Sir William Bonville (1392–1461), of Shute. Sir Philip's eldest son and heir Sir William Courtenay (d.1485) had married Bonville's daughter Margaret, cementing the alliance between the two men. On 3 November 1455 Thomas de Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon (1414–1458) at the head of a private army of 1,000 men seized control of Exeter and its royal castle, the stewardship of which was sought by Bonville, and laid siege to nearby Powderham for two months. Lord Bonville attempted to raise the siege and approached from the east, crossing the River Exe, but was unsuccessful and was driven back by the Earl's forces. Sir Philip otherwise played a limited role in the Bonville-Courtenay feud. On 15 December 1455 the Earl of Devon and Lord Bonville met decisively at the Battle of Clyst Heath, where Bonville was defeated and after which the Earl sacked and pillaged Shute.[10]

Sir Philip swore fealty to King Edward IV (1461-1483) as an MP at Parliament.

Marriage & progeny

In about 1426 Courtenay married Elizabeth Hungerford, daughter of Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford, Speaker of the House of Commons, Steward of the Household to KingsHenry V and Henry VI, and Lord High Treasurer. They had seven sons and four daughters: [11]

- Sir William Courtenay (c. 1428 – September 1485) of Powderham, who married Margaret Bonville, daughter of William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville (died 1461).

- Sir Philip Courtenay of Molland (died 7 December 1489), second son, MP, Sheriff of Devon in 1470, whose daughter Elizabeth became the wife of her cousin Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (by the 1485 creation). The Devon manor of Molland was given to him by his mother who had herself been given it as her marriage portion by her brother Robert Hungerford, 2nd Baron Hungerford (died 1459) who had himself received it from his wife Margaret de Botreaux, daughter and sole heiress of William de Botreaux, 3rd Baron Botreaux (died 1462). The family of Courtenay of Molland continued at Molland until the death of the last in the male line in 1732.

- Peter Courtenay (died 22 September 1492), Bishop of Exeter and Bishop of Winchester.

- Sir Walter Courtenay (died 7 November 1506), who married Alice Colbroke, widow of John Vere (died before 15 March 1488), son of Sir Robert Vere (1410-1461), of Haccombe, Devon, by Joan Courtenay (died before 3 August 1465), widow of Sir Nicholas Carew (died before 20 April 1448), and daughter of Sir Hugh Courtenay by Philippa Archdekne.[12]

- Sir Edmund Courtenay, who married Jane Devioke, dau. of John Deviock of Deviock near St Germans, and Isabell

- Humphrey Courtenay.

- Sir John Courtenay.

- Anne Courtenay, who married Sir Thomas Grenville.

- Elizabeth Courtenay, who married firstly Sir James Luttrell, secondly Sir Humphrey Audley, and thirdly Thomas Malet.

- Philippe Courtenay, who married Sir Thomas Fulford.

- Katherine Courtenay (died 12 January 1515), who married thrice:

- Firstly Sir Seintclere Pomeroy (died 31 May 1471),

- Secondly Thomas Rogers,

- Thirdly Sir William Huddesfield (died 20 March 1499).[13] of Shillingford St. George, Attorney General to King Edward IV. His monumental brass exists in Shillingford Church (with a copy rubbing framed in Powderham Castle Chapel) showing him dressed as a knight in armour, with sword and spurs. He is bare-headed, and wears over his armour a tabard, on which is embroidered the arms of Huddesfield: Argent, a fess between three boars passant sable, on the fess a crescent for difference. He kneels before a prie dieu, on which is an open book, and on the floor by his side lie his gauntlets, and helmet with mantling and crest, a boar rampant. Katherine his wife kneels behind the knight. She wears a pedimental head dress and lappets, gown, ornamented girdle, with dependant pomander. Over this she wears a robe of estate, on which is her arms: Or, three torteaux a label of three, for Courtenay. Behind her kneels her only son by her second husband, George Rogers, and following them her two daughters, by Sir William Huddesfield, in similar costume to their mother, Elizabeth Poyntz, and Katherine Carew. Below is this inscription (the abbreviations of the Latin extended): Conditor et Redemptor corporis et et anime Sit michi medicus et custos utriusque. Dame Kateryn ye wife of Sr Willm Huddesfeld & dought of S'r Phil' Courtnay kny'kt. In the centre of the cover-stone of the tomb is a shield with the arms of Huddesfield impaling Courtenay. When Westcote, in 1630, visited the church, he noted this inscription, which was probably on the ledger line round the table of the tomb, and has since disapappeared : "Here lieth Sir William Huddiffeild, knight, Attorney-general to King Edward IV, and of the Council to King Henry VII, and Justice of Oyer and Determiner; which died the l0th day of March, in the year of our Lord, 1499. On whose soul Jesus have mercy, Amen. Honor Deo et Gloria" [14]

Death

He died on 16 December 1463.

Notes

- ↑ This branch of the family is traditionally termed "of Powderham" to distinguish it from the senior line of Courtenay, Earls of Devon. Eventually, after the extinction of the senior line, the Powderham branch inherited the Earldom of Devon.

- ↑ Maria Halliday, A Delineation of the Courtenay Mantelpiece in the Episcopal Palace at Exeter by Roscoe Gibbs, Torquay, 1884

- ↑ Vivian, p.246 "Joan", but "Agnes or Joan" per French, Daniel (Ed.), Powderham Castle: Historic Family Home of the Earls of Devon, 2011. Visitor guidebook, p.6

- ↑ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitation of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, pp.243-253. Pedigree of Courtenay, p.246

- ↑ Vivian, p.162, pedigree of Champernowne; p.189, pedigree of Chudleigh of Ashton

- ↑ Vivian, p.246, pedigree of Courtenay; Vivian, p.162, pedigree of Champernowne

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Vivian, p.162, pedigree of Champernowne

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Vivian, p.246, pedigree of Courtenay

- ↑ Richardson II 2011, pp. 28–30

- ↑ Powderham Castle guide book, p.9

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas, Representation & Rebellion in the Later Middle Ages, published in Kain, Roger & Ravenhill, William, (eds.) Historical Atlas of South-West England, Exeter, 1999, pp. 141, 144

- ↑ Richardson II 2011, pp. 30–1, 327, 427–8.

- ↑ Richardson IV 2011, pp. 271–3; Richardson II 2011, pp. 326–7.

- ↑ Richardson II 2011, pp. 30–1; Richardson III 2011, pp. 395–6

- ↑ Rogers, W.H.Hamilton., Sir William Huddesfield and Katherine Courtenay his Wife, Shillingford Church, Devon, Published in Wiltshire Notes & Queries, Vol.3, 1899-1901, pp.336-345

References

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G., ed. Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families II (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 1449966381.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G., ed. Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families III (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 144996639X.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G., ed. Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 1460992709.

External links

- Cokayne, George Edward (1916). Doubleday, H.A., ed. The Complete Peerage IV. London: St. Catherine Press.

- Vivian, John Lambrick, ed. (1887). The visitations of Cornwall, comprising the heralds' visitations of 1530, 1573, and 1620. With additions ... Exeter: William Pollard & Company. p. 108. (Courtenay pedigree)