Sinuosity

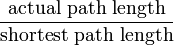

Sinuosity, sinuosity index, or sinuosity coefficient of a continuously derivable curve having at least one inflection point is the ratio of the curvilinear length (along the curve) and the distance (straight line) between the end points of the curve. This dimensionless quantity is obtained by the following report:

The value ranges from 1 (case of straight line) to infinity (case of a closed loop, where the shortest path length is zero) or for an infinitely-long actual path.[1]

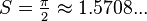

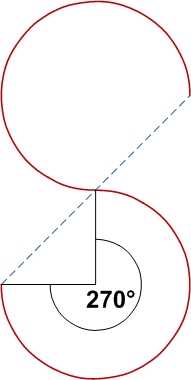

The sinuosity S of:

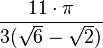

- 2 inverted continuous semicircles located in the same plane is

. It is independent of the circle radius;

. It is independent of the circle radius;

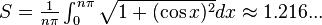

- a sine function (over a whole number n of half-periods), which can be calculated by computing the sine curve's arclength on those periods, is

The curve must be continuous (no jump) between the two ends. The sinuosity value is really significant when the line is continuously differentiable (no angular point). The distance between both ends can also be evaluated by a plurality of segments according to a broken line passing through the successive inflection points (sinuosity of order 2).

The calculation of the sinuosity is valid in a 3-dimensional space (e.g. for the central axis of the small intestine), although it is often performed in a plane (with then a possible orthogonal projection of the curve in the selected plan; "classic" sinuosity on the horizontal plane, longitudinal profile sinuosity on the vertical plane).

The classification of a sinuosity (e.g. strong / weak) often depends on the cartographic scale of the curve and of the object velocity which flowing therethrough (river, avalanche, car, bicycle, bobsleigh, skier, high speed train, etc.): the sinuosity of the same curved line could be considered very strong for a high speed train but low for a river. Nevertheless, it is possible to see a very strong sinuosity in the succession of few river bends, or of laces on some mountain roads.

Rivers

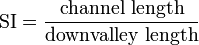

In studies of rivers, the sinuosity index is similar but not identical to the general form given above, being given by:

The difference from the general form happens because the downvalley path is not perfectly straight. The sinuosity index can be explained, then, as the deviations from a path defined by the direction of maximum downslope. For this reason, bedrock streams that flow directly downslope have a sinuosity index of 1, and meandering streams have a sinuosity index that is greater than 1.[2]

It is also possible to distinguish the case where the stream flowing on the line could not physically travel the distance between the ends: in some hydraulic studies, this leads to assign a sinuosity value of 1 for a torrent flowing over rocky bedrock along a horizontal rectilinear projection, even if the slope angle varies.

For rivers, the conventional classes of sinuosity, SI, are:

- SI <1.05: almost straight

- 1.05 ≤ SI <1.25: winding

- 1.25 ≤ SI <1.50: twisty

- 1.50 ≤ SI: meandering

It has been claimed that river shapes are governed by a self-organizing system that causes their average sinuosity (measured in terms of the source-to-mouth distance, not channel length) to be π,[3] but this has not been borne out by later studies, which found an average value less than 2.[4]

Remarkable values

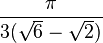

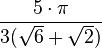

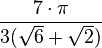

With similar opposite arcs joints in the same plane, continuously differentiable:

| Central angle | Sinuosity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Degrees | Radians | Exact | Decimal |

| 30° |  |

| 1.0115 |

| 60° |  |

| 1.0472 |

| 90° |  |

| 1.1107 |

| 120° |  |

| 1.2092 |

| 150° |  |

| 1.3552 |

| 180° |  |

| 1.5708 |

| 210° |  |

| 1.8972 |

| 240° |  |

| 2.4184 |

| 270° |  |

| 3.3322 |

| 300° |  |

| 5.2360 |

| 330° |  |

| 11.1267 |

See also

References

- ↑ Leopold, Luna B., Wolman, M.G., and Miller, J.P., 1964, Fluvial Processes in Geomorphology, San Francisco, W.H. Freeman and Co., 522p.

- ↑ Mueller, Jerry (1968). "An Introduction to the Hydraulic and Topographic Sinuosity Indexes1". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 58 (2): 371. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1968.tb00650.x.

- ↑ Stølum, Hans-Henrik, "River Meandering as a Self-Organization Process", Science 271 (5256): 1710–1713, Bibcode:1996Sci...271.1710S, doi:10.1126/science.271.5256.1710.

- ↑ Grime, James (March 14, 2015), "A meandering tale: the truth about pi and rivers", Alex Bellos's Adventures in Numberland, The Guardian.