Singleton (mathematics)

In mathematics, a singleton, also known as a unit set,[1] is a set with exactly one element. For example, the set {0} is a singleton.

The term is also used for a 1-tuple (a sequence with one element).

Properties

Within the framework of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, the axiom of regularity guarantees that no set is an element of itself. This implies that a singleton is necessarily distinct from the element it contains,[1] thus 1 and {1} are not the same thing, and the empty set is distinct from the set containing only the empty set. A set such as {{1, 2, 3}} is a singleton as it contains a single element (which itself is a set, however, not a singleton).

A set is a singleton if and only if its cardinality is 1. In the standard set-theoretic construction of the natural numbers, the number 1 is defined as the singleton {0}.

In axiomatic set theory, the existence of singletons is a consequence of the axiom of pairing: for any set A, the axiom applied to A and A asserts the existence of {A, A}, which is the same as the singleton {A} (since it contains A, and no other set, as an element).

If A is any set and S is any singleton, then there exists precisely one function from A to S, the function sending every element of A to the single element of S. Thus every singleton is a terminal object in the category of sets.

A singleton is furthermore characterized by the property that every function from a singleton to any arbitrary set is injective. This actually is equivalent to the definition of singleton.

In category theory

Structures built on singletons often serve as terminal objects or zero objects of various categories:

- The statement above shows that the singleton sets are precisely the terminal objects in the category Set of sets. No other sets are terminal.

- Any singleton admits a unique topological space structure (both subsets are open). These singleton topological spaces are terminal objects in the category of topological spaces and continuous functions. No other spaces are terminal in that category.

- Any singleton admits a unique group structure (the unique element serving as identity element). These singleton groups are zero objects in the category of groups and group homomorphisms. No other groups are terminal in that category.

Definition by indicator functions

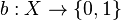

Let  be a class defined by an indicator function

be a class defined by an indicator function

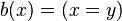

.

.

Then  is called a singleton if and only if there is some y ∈ X such that for all x ∈ X,

is called a singleton if and only if there is some y ∈ X such that for all x ∈ X,

.

.

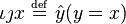

Traditionally, this definition was introduced by Whitehead and Russell[2] along with the definition of the natural number 1, as

, where

, where  .

.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Stoll, Robert (1961). Sets, Logic and Axiomatic Theories. W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Whitehead, Alfred North; Bertrand Russell (1910). Principia Mathematica. p. 37.