Sine wave

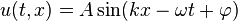

The sine wave or sinusoid is a mathematical curve that describes a smooth repetitive oscillation. It is named after the function sine, of which it is the graph. It occurs often in pure and applied mathematics, as well as physics, engineering, signal processing and many other fields. Its most basic form as a function of time (t) is:

where:

- A, the amplitude, is the peak deviation of the function from zero.

- f, the ordinary frequency, is the number of oscillations (cycles) that occur each second of time.

- ω = 2πf, the angular frequency, is the rate of change of the function argument in units of radians per second

-

, the phase, specifies (in radians) where in its cycle the oscillation is at t = 0.

, the phase, specifies (in radians) where in its cycle the oscillation is at t = 0.

- When

is non-zero, the entire waveform appears to be shifted in time by the amount

is non-zero, the entire waveform appears to be shifted in time by the amount  /ω seconds. A negative value represents a delay, and a positive value represents an advance.

/ω seconds. A negative value represents a delay, and a positive value represents an advance.

- When

|

Sine wave

2 seconds of a 220 Hz sine wave |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The sine wave is important in physics because it retains its wave shape when added to another sine wave of the same frequency and arbitrary phase and magnitude. It is the only periodic waveform that has this property. This property leads to its importance in Fourier analysis and makes it acoustically unique.

General form

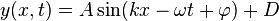

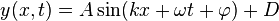

In general, the function may also have:

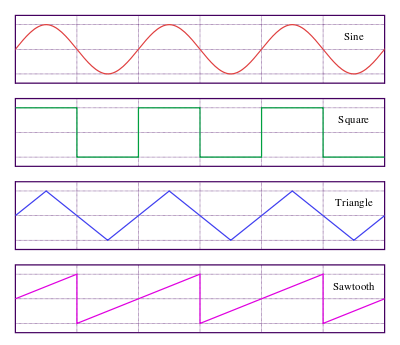

- a spatial variable x that represents the position on the dimension on which the wave propagates, and a characteristic parameter k called wave number (or angular wave number), which represents the proportionality between the angular frequency ω and the linear speed (speed of propagation) ν

- a non-zero center amplitude, D

which is

, if the wave is moving to the right

, if the wave is moving to the right , if the wave is moving to the left

, if the wave is moving to the left

[1] The wavenumber is related to the angular frequency by:.

where λ is the wavelength, f is the frequency, and v is the linear speed.

This equation gives a sine wave for a single dimension; thus the generalized equation given above gives the displacement of the wave at a position x at time t along a single line. This could, for example, be considered the value of a wave along a wire.

In two or three spatial dimensions, the same equation describes a travelling plane wave if position x and wavenumber k are interpreted as vectors, and their product as a dot product. For more complex waves such as the height of a water wave in a pond after a stone has been dropped in, more complex equations are needed.

Occurrences

This wave pattern occurs often in nature, including ocean waves, sound waves, and light waves.

A cosine wave is said to be "sinusoidal", because  which is also a sine wave with a phase-shift of π/2 radians. Because of this "head start", it is often said that the cosine function leads the sine function or the sine lags the cosine.

which is also a sine wave with a phase-shift of π/2 radians. Because of this "head start", it is often said that the cosine function leads the sine function or the sine lags the cosine.

The human ear can recognize single sine waves as sounding clear because sine waves are representations of a single frequency with no harmonics; some sounds that approximate a pure sine wave are whistling, a crystal glass set to vibrate by running a wet finger around its rim, and the sound made by a tuning fork.

To the human ear, a sound that is made of more than one sine wave will have perceptible harmonics; addition of different sine waves results in a different waveform and thus changes the timbre of the sound. Presence of higher harmonics in addition to the fundamental causes variation in the timbre, which is the reason why the same musical note (the same frequency) played on different instruments sounds differently. On the other hand, if the sound contains aperiodic waves along with sine waves (which are periodic), then the sound will be perceived "noisy" as noise is characterized as being aperiodic or having a non-repetitive pattern.

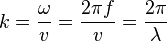

Fourier series

In 1822, French mathematician Joseph Fourier discovered that sinusoidal waves can be used as simple building blocks to describe and approximate any periodic waveform, including square waves. Fourier used it as an analytical tool in the study of waves and heat flow. It is frequently used in signal processing and the statistical analysis of time series.

Traveling and standing waves

Since sine waves propagate without changing form in distributed linear systems, they are often used to analyze wave propagation. Sine waves traveling in two directions in space can be represented as

When two waves having the same amplitude and frequency, and traveling in opposite directions, superpose each other, then a standing wave pattern is created. Note that, on a plucked string, the interfering waves are the waves reflected from the fixed end points of the string. Therefore, standing waves occur only at certain frequencies, which are referred to as resonant frequencies and are composed of a fundamental frequency and its higher harmonics. The resonant frequencies of a string are determined by the length between the fixed ends and the tension of the string.

See also

- Crest (physics)

- Fourier transform

- Harmonic series (mathematics)

- Harmonic series (music)

- Helmholtz equation

- Instantaneous phase

- Pure tone

- Simple harmonic motion

- Sinusoidal model

- Wave (physics)

- Wave equation

References

- ↑ Resnick Halliday Walker, Fundamentals of Physics

Further reading

- "Sinusoid". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Springer. Retrieved December 8, 2013.