Sine and cosine transforms

In mathematics, the Fourier sine and cosine transforms are forms of the Fourier integral transform that do not use complex numbers. They are the forms originally used by Joseph Fourier and are still preferred in some applications, such as signal processing or statistics.

Definition

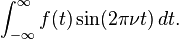

The Fourier sine transform of f (t), sometimes denoted by either  or

or  , is

, is

If t means time, then ν is frequency in cycles per unit time, but in the abstract, they can be any pair of variables which are dual to each other.

This transform is necessarily an odd function of frequency, i.e. for all ν:

The numerical factors in the Fourier transforms are defined uniquely only by their product. Here, in order that the Fourier inversion formula not have any numerical factor, the factor of 2 appears because the sine function has L2 norm of

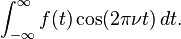

The Fourier cosine transform of f (t), sometimes denoted by either  or

or  , is

, is

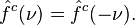

It is necessarily an even function of frequency, i.e. for all ν:

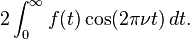

Some authors[1] only define the cosine transform for even functions of t, in which case its sine transform is zero. Since cosine is also even, a simpler formula can be used,

Similarly, if f is an odd function, then the cosine transform is zero and the sine transform can be simplified to

Fourier inversion

The original function f can be recovered from its transforms under the usual hypotheses, that f and both of its transforms should be absolutely integrable. For more details on the different hypotheses, see Fourier inversion theorem.

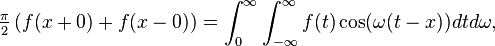

The inversion formula is[2]

which has the advantage that all frequencies are positive and all quantities are real. If the numerical factor 2 is left out of the definitions of the transforms, then the inversion formula is usually written as an integral over both negative and positive frequencies.

Using the addition formula for cosine, this is sometimes rewritten as

where f (x + 0) denotes the one-sided limit of f as x approaches zero from above, and f (x − 0) denotes the one-sided limit of f as x approaches zero from below.

If the original function f is an even function, then the sine transform is zero; if f is an odd function, then the cosine transform is zero. In either case, the inversion formula simplifies.

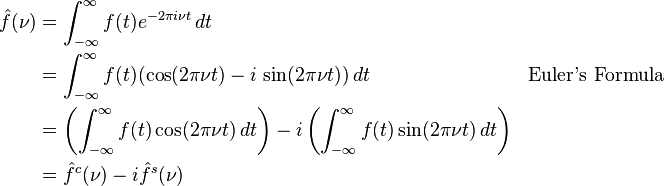

Relation with complex exponentials

The form of the Fourier transform used more often today is

See also

References

- Whittaker, Edmund, and James Watson, A Course in Modern Analysis, Fourth Edition, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1927, pp. 189, 211

- ↑ Mary L. Boas, Mathematical Methods in the Physical Sciences, 2nd Ed, John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1983. ISBN 0-471-04409-1

- ↑ Poincaré, Henri (1895). Theorie analytique de la propagation de chaleur. Paris: G. Carré. pp. pp. 108ff.