Sima Qian

| Sima Qian | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

c. 145 or 135 BC Longmen, Han China (now Hejin, Shanxi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 86 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Historian | ||||||||||||||||||||||

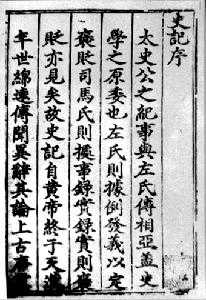

| Known for | Records of the Grand Historian | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Sima Tan (father) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 司馬遷 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 司马迁 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (personal name) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zizhang | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 子長 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 子长 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (courtesy name) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Sima Qian (c. 145 or 135 – 86 BC), formerly romanized Ssu-ma Chien, was a Chinese historian of the Han dynasty. He is considered the father of Chinese historiography for his work, the Records of the Grand Historian, a Jizhuanti-style (history presented in a series of biographies) general history of China, covering more than two thousand years from the Yellow Emperor to his time, during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han. Although he worked as the Court Astrologer (Chinese: 太史令; Tàishǐ Lìng), later generations refer to him as the Grand Historian (Chinese: 太史公; Tàishǐ Gōng or tai-shih-kung) for his monumental work; a work which in later generations would often only be somewhat tacitly or glancingly acknowledged as an achievement only made possible by his acceptance and endurance of punitive actions against him, including imprisonment, castration, and subjection to servility.

Early life and education

Sima Qian was born and grew up in Longmen, near present-day Hancheng in a family of astrologers. His father, Sima Tan, served as the Court Astrologer, a versatile technical position trained in various matters.[1] His main responsibilities were managing the imperial library and maintaining or reforming the calendar. Due to intensive training by his father, by the age of ten, Sima Qian was already well versed in old writings. He was a student of the famous Confucians Kong Anguo and Dong Zhongshu. At the age of twenty, Sima Qian started a journey throughout the country, visiting ancient monuments, and sought for the graves of the ancient sage kings Yu on Mount Kuaiji and Shun in Hunan.[2] Places he visited include Shandong, Yunnan, Hebei, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, and Hunan.

As Han court official

After his travels, Sima was chosen to be a Palace Attendant in the government, whose duties were to inspect different parts of the country with Emperor Wu. In 110 BC, at the age of thirty-five, Sima Qian was sent westward on a military expedition against some "barbarian" tribes. That year, his father fell ill and could not attend the Imperial Feng Sacrifice. Suspecting his time was running out, he summoned his son back home to complete the historical work he had begun. Sima Tan wanted to follow the Annals of Spring and Autumn - the first chronicle in the history of Chinese literature. Fueled by his father's inspiration, Sima Qian started to compile Shiji, which became known in English as the Records of the Grand Historian, in 109 BC. Three years after the death of his father, Sima Qian assumed his father's previous position as Court Astrologer. In 105 BC, Sima was among the scholars chosen to reform the calendar. As a senior imperial official, Sima was also in the position to offer counsel to the emperor on general affairs of state.

The Li Ling affair

In 99 BC, Sima Qian became embroiled in the Li Ling affair, where Li Ling and Li Guangli (李广利), two military officers who led a campaign against the Xiongnu in the north, were defeated and taken captive. Emperor Wu attributed the defeat to Li Ling, with all government officials subsequently condemning him for it. Sima was the only person to defend Li Ling, who had never been his friend but whom he respected. Emperor Wu interpreted Sima's defence of Li Ling as an attack on his brother-in-law, who had also fought against the Xiongnu without much success, and sentenced Sima to death. At that time, execution could be commuted either by money or castration. Since Sima did not have enough money to atone his "crime", he chose the latter and was then thrown into prison, where he endured three years. He described his pain thus: "When you see the jailer you abjectly touch the ground with your forehead. At the mere sight of his underlings you are seized with terror... Such ignominy can never be wiped away."

In 96 BC, on his release from prison, Sima chose to live on as a palace eunuch to complete his histories, rather than commit suicide as was expected of a gentleman-scholar. As Sima Qian himself explained in his Letter to Ren An:

| “ | If even the lowest slave and scullion maid can bear to commit suicide, why should not one like myself be able to do what has to be done? But the reason I have not refused to bear these ills and have continued to live, dwelling in vileness and disgrace without taking my leave, is that I grieve that I have things in my heart which I have not been able to express fully, and I am shamed to think that after I am gone my writings will not be known to posterity. Too numerous to record are the men of ancient times who were rich and noble and whose names have yet vanished away. It is only those who were masterful and sure, the truly extraordinary men, who are still remembered. ... I too have ventured not to be modest but have entrusted myself to my useless writings. I have gathered up and brought together the old traditions of the world which were scattered and lost. I have examined the deeds and events of the past and investigated the principles behind their success and failure, their rise and decay, in one hundred and thirty chapters. I wished to examine into all that concerns heaven and man, to penetrate the changes of the past and present, completing all as the work of one family. But before I had finished my rough manuscript, I met with this calamity. It is because I regretted that it had not been completed that I submitted to the extreme penalty without rancor. When I have truly completed this work, I shall deposit it in the Famous Mountain. If it may be handed down to men who will appreciate it, and penetrate to the villages and great cities, then though I should suffer a thousand mutilations, what regret should I have? | ” |

Historian

Although the style and form of Chinese historical writings varied through the ages, Shiji has defined the quality and style from then onwards. Before Sima, histories were written as certain events or certain periods of history of states; his idea of a general history affected later historiographers like Zheng Qiao (郑樵) in writing Tongshi (通史) and Sima Guang in writing Zizhi Tongjian. The Chinese historical form of dynasty history, or jizhuanti history of dynasties, was codified in the second dynastic history by Ban Gu's Book of Han, but historians regard Sima's work as their model, which stands as the "official format" of the history of China.

In writing Shiji, Sima initiated a new writing style by presenting history in a series of biographies. His work extends over 130 chapters — not in historical sequence, but divided into particular subjects, including annals, chronicles, and treatises — on music, ceremonies, calendars, religion, economics, and extended biographies. Sima's work influenced the writing style of other histories outside of China as well, such as the Goryeo (Korean) history the Samguk Sagi (三国史记).

Sima adopted a new method in sorting out the historical data and a new approach to writing historical records. He analyzed the records and sorted out those that could serve the purpose of Shiji. He intended to discover the patterns and principles of the development of human history. Sima also emphasized, for the first time in Chinese history, the role of individual men in affecting the historical development of China and his historical perception that a country cannot escape from the fate of growth and decay.

Unlike the Book of Han, which was written under the supervision of the imperial dynasty, Shiji was a privately written history since he refused to write Shiji as an official history covering only those of high rank. The work also covers people of the lower classes and is therefore considered a "veritable record" of the darker side of the dynasty.

Literary figure

Sima's Shiji is respected as a model of biographical literature with high literary value and still stands as a textbook for the study of classical Chinese. Sima's works were influential to Chinese writing, serving as ideal models for various types of prose within the neo-classical ("renaissance" 复古) movement of the Tang-Song period. The great use of characterisation and plotting also influenced fiction writing, including the classical short stories of the middle and late medieval period (Tang-Ming) as well as the vernacular novel of the late imperial period.

His influence was derived primarily from the following elements of his writing: his skillful depiction of historical characters using details of their speech, conversations, and actions; his innovative use of informal, humorous, and varied language (even Lu Xun regarded Shiji as "the historians' most perfect song, a "Li Sao" without the rhyme" (史家之绝唱,无韵之离骚) in his "Hanwenxueshi Gangyao" (《汉文学史纲要》); and the simplicity and conciseness of his style.

Other literary works

Sima's famous letter to his friend Ren An about his sufferings during the Li Ling Affair and his perseverance in writing Shiji is today regarded as a highly admired example of literary prose style, studied widely in China even today.

Sima Qian wrote eight rhapsodies (fu 赋), which are listed in the bibliographic treatise of the Book of Han. All but one, the "Rhapsody in Lament for Gentleman who do not Meet their Time" (士不遇赋) have been lost, and even the surviving example is probably not complete.

Astrologer

Sima and his father were both court astrologers (taishi) 太史 in the Former Han Dynasty. At that time, the astrologer had an important role, responsible for interpreting and predicting the course of government according to the influence of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as other phenomena such as solar eclipses and earthquakes.

Before compiling Shiji, in 104 BC, Sima Qian created Taichuli (太初历) which can be translated as 'The first calendar' on the basis of the Qin calendar. Taichuli was one of the most advanced calendars of the time. The creation of Taichuli was regarded as a revolution in the Chinese calendar tradition, as it stated that there were 365.25 days in a year and 29.53 days in a month.

The minor planet 12620 Simaqian is named in his honour.

Footnotes

- ↑ de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A biographical dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Brill. p. 1222. ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- ↑ Burton Watson (1958). "The Biography of Ssu Ma Ch'ien". Ssu Ma Ch'ien Grand Historian Of China. Columbia University Press. p. 47.

- ↑ Burton Watson (1958). "The Biography of Ssu Ma Ch'ien". Ssu Ma Ch'ien Grand Historian Of China. Columbia University Press. pp. 57–67.

Further reading

- Burton Watson (1958) Ssu-ma Ch'ien: Grand Historian of China. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Martin, Thomas R. (2009). Herodotus and Sima Qian: The First Great Historians of Greece and China. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

- Robert Bonnaud (2007) Essays of comparative history. Polybus and Sima Qian (in French). Condeixa : La Ligne d'ombre .

- W.G. Beasley and E.G. Pulleyblank (1961) Historians of China and Japan. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stephen W. Durrant (1995), The Cloudy Mirror: Tension and Conflict in the Writings of Sima Qian. Albany : State University of New York Press.

- Grant Ricardo Hardy (1988) Objectivity and Interpretation in the "Shi Chi". Yale University.

- Burton Watson (1958) Ssu-ma Ch'ien: Grand Historian of China. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Joseph Roe Allen III. Chinese Texts: Narrative Records of the Historian

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sima Qian |

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sima Qian. |

- Works by Sima Qian at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sima Qian at Internet Archive

- Works by Sima Qian at Open Library

- Significance of Shiji on literature

- Sima Qian: China's 'grand historian', article by Carrie Gracie in BBC News Magazine, 7 October 2012

| ||||||

|