Silicon-tin

| Silicon-tin | |

|---|---|

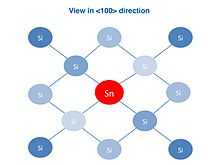

The view of the SiSn lattice as seen from the <100> direction. Silicon atoms further from the cross-section are displayed using a lighter shade of blue. The red atom is the Sn atom occupying a silicon lattice point. | |

| Type | Alloy |

Silicon-tin or SiSn, is in general a term used for an alloy of the form Si(1-x)Snx. The molecular ratio of tin in silicon can vary based on the fabrication methods or doping conditions. In general, SiSn is known to be intrinsically semiconducting,[1] and even small amounts of Sn doping in silicon can also be used to create strain in the silicon lattice and alter the charge transport properties.[2]

Theoretical studies

Several theoretical works have shown SiSn to be semiconducting.[3][4] These mainly include density functional theory-based studies. The band structures obtained using these works show a change in band gap of silicon with the inclusion of tin into the silicon lattice. Thus, like SiGe, SiSn has a variable band gap that can be controlled using Sn concentration as a variable.

Production

SiSn can be obtained experimentally using several approaches. For small quantity of Sn in silicon, the Czochralski process is well known.[5][6] Diffusion of tin into silicon has also been tried extensively in the past.[7][8] Sn has the same valency and electronegativity as silicon and can be found in the diamond cubic crystal structure (α-Sn). Thus, silicon and tin meet three out of the four Hume-Rothery rules for solid state solubility. The one criterion that is not met is that of difference in atomic size. The tin atom is substantially bigger than the silicon atom (31.8%). This reduces the solid state solubility of tin in silicon.[9]

Electrical performance

The first Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor using SiSn as a channel material was shown in 2013.[10] This study proved that SiSn can be used as semiconductor for MOSFET fabrication, and that there may be certain applications where the use of SiSn instead of silicon may be more advantageous. In particular, the off current of SiSn transistors is much lower than that of silicon transistors.[11][12] Thus, logic circuits based on SiSn MOSFETs consume lower static power compared to silicon based circuits. This is advantageous in battery operated devices (LSTP devices), where the standby power has to be reduced for longer battery life.

See also

Silicon germanium

References

- ↑ Jensen, Rasmus V S; Pedersen, Thomas G; Larsen, Arne N (31 August 2011). "Quasiparticle electronic and optical properties of the Si–Sn system". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 23 (34): 345501. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/23/34/345501.

- ↑ Simoen, E.; Claeys, C. (2000). "Tin Doping Effects in Silicon". Electrochem. Soc. Proc. 2000-17: 223.

- ↑ Amrane, Na.; Ait Abderrahmane, S.; Aourag, H. (August 1995). "Band structure calculation of GeSn and SiSn". Infrared Physics & Technology 36 (5): 843–848. doi:10.1016/1350-4495(95)00019-U.

- ↑ Zaoui, A.; Ferhat, M.; Certier, M.; Khelifa, B.; Aourag, H. (June 1996). "Optical properties of SiSn and GeSn". Infrared Physics & Technology 37 (4): 483–488. doi:10.1016/1350-4495(95)00116-6.

- ↑ Claeys, C.; Simoen, E.; Neimash, V. B.; Kraitchinskii, A.; Kras’ko, M.; Puzenko, O.; Blondeel, A.; Clauws, P. (2001). "Tin Doping of Silicon for Controlling Oxygen Precipitation and Radiation Hardness". Journal of the Electrochemical Society 148 (12): G738. doi:10.1149/1.1417558.

- ↑ Chroneos, A.; Londos, C. A.; Sgourou, E. N. (2011). "Effect of tin doping on oxygen- and carbon-related defects in Czochralski silicon". Journal of Applied Physics 110 (9): 093507. doi:10.1063/1.3658261.

- ↑ Kringhøj, Per; Larsen, Arne (September 1997). "Anomalous diffusion of tin in silicon". Physical Review B 56 (11): 6396–6399. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.56.6396.

- ↑ Yeh, T. H. (1968). "Diffusion of Tin into Silicon". Journal of Applied Physics 39 (9): 4266. doi:10.1063/1.1656959.

- ↑ Akasaka, Youichi; Horie, Kazuo; Nakamura, Genshiro; Tsukamoto, Katsuhiro; Yukimoto, Yoshinori (October 1974). "Study of Tin Diffusion into Silicon by Backscattering Analysis". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 13 (10): 1533–1540. doi:10.1143/JJAP.13.1533.

- ↑ Hussain, Aftab M.; Fahad, Hossain M.; Singh, Nirpendra; Sevilla, Galo A. Torres; Schwingenschlögl, Udo; Hussain, Muhammad M. (2013). "Exploring SiSn as channel material for LSTP device applications". Device Research Conference (DRC), 2013 71st Annual: 93–94. doi:10.1109/DRC.2013.6633809. ISBN 978-1-4799-0814-1.

- ↑ Hussain, Aftab M.; Fahad, Hossain M.; Singh, Nirpendra; Sevilla, Galo A. Torres; Schwingenschlögl, Udo; Hussain, Muhammad M. (13 January 2014). "Tin - an unlikely ally for silicon field effect transistors?". Physica status solidi (RRL) - Rapid Research Letters: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1002/pssr.201308300.

- ↑ Hussain, Aftab M.; Fahad, Hossain M.; Singh, Nirpendra; Sevilla, Galo A. Torres; Schwingenschlögl, Udo; Hussain, Muhammad M. (2013). "Tin (Sn) for enhancing performance in silicon CMOS". Nanotechnology Materials and Devices Conference (NMDC), 2013 IEEE: 13–15. doi:10.1109/NMDC.2013.6707470. ISBN 978-1-4799-3387-7.