Silanes

Silanes are saturated chemical compounds, which means that they consist of one or multiple silicon atoms linked to each other or one or multiple atoms of other chemical elements as the tetrahedral centers of multiple single bonds. By definition, cycles are excluded, so that the silanes comprise a homologous series of inorganic compounds with the general formula Si

nH

2n + 2. Commercially available silanes are synthetically derived.

Each silicon atom has four bonds (either Si-H or Si-Si bonds), and each hydrogen atom is joined to a silicon atom (H-Si bonds). A series of linked silicon atoms is known as the silicon skeleton or silicon backbone. The number of silicon atoms is used to define the size of the silane (e.g., Si2-silane).

Related to silanes, is a homologous series of functional groups, side-chains or radicals with the general formula Si

nH

2n + 2. Examples include silyl and disilanyl.

The simplest possible silane (the parent molecule) is silane, SiH

4. There is no limit to the number of silicon atoms that can be linked together, the only limitation being that the molecule is acyclic, is saturated, and is a hydrosilicon.

Silanes are very reactive and have moderate biological activity.

Much of the early work establishing that silicon does indeed form a homologous series of hydride analogous to the alkanes, albeit to a much smaller extent, was conducted by Alfred Stock and Carl Somiesky.[1] Although monosilane and disilane were already known, Stock and Somiesky discovered, beginning in 1916, the next four members of the SinH2n+2 series, up to n = 6, and they also documented the formation of solid phase polymeric silicon hydrides (see below).[2] Usually polymeric silanyl hydrides are based on silicone and thus called silicone hydrides (the back bone consists of Si-O-Si bonds).

Structure classification

Saturated hydrosilicons can be:

- linear (general formula SinH2n + 2) wherein the silicon atoms are joined in a snake-like structure

- branched (general formula SinH2n + 2, n > 3) wherein the silicon backbone splits off in one or more directions

- cyclic (general formula SinH2n, n > 2) wherein the silicon backbone is linked so as to form a loop.

According to the definition by IUPAC, the former two are silanes, whereas the third group is called cyclosilanes. Saturated hydrosilicons can also combine any of the linear, cyclic (e.g., polycyclic) and branching structures, and they are still silanes (no general formula) as long as they are acyclic (i.e., having no loops). They also have single covalent bonds between their silicons.

Isomerism

Silanes with more than three silicon atoms can be arranged in various ways, forming structural isomers. The simplest isomer of a silane is the one in which the silicon atoms are arranged in a single chain with no branches. This isomer is sometimes called the n-isomer (n for "normal", although it is not necessarily the most common). However the chain of silicon atoms may also be branched at one or more points. The number of possible isomers increases rapidly with the number of silicon atoms. For example:

- Si1: no isomers: silane

- Si2: no isomers: disilane

- Si3: no isomers: trisilane

- Si4: two isomers: tetrasilane & isotetrasilane

- Si5: three isomers: pentasilane, isopentasilane & neopentasilane

- Si6: five isomers: hexasilane, isohexasilane, 3-silylpentasilane, neohexasilane & 2,3-disilanyltetrasilane

- Si12: 355 isomers

- Si32: 27,711,253,769 isomers

- Si60: 22,158,734,535,770,411,074,184 isomers, many of which are not stable

Branched silanes can be chiral. For example 3-silylhexasilane and its higher homologues are chiral due to their stereogenic center at silicon atom number three. In addition to these isomers, the chain of silicon atoms may form one or more loops. Such compounds are called cyclosilanes.

Nomenclature

The IUPAC nomenclature (systematic way of naming compounds) for silanes is based on identifying hydrosilicon chains. Unbranched, saturated hydrosilicon chains are named systematically with a Greek numerical prefix denoting the number of silicons and the suffix "-silane".

Linear silanes

Straight-chain silanes are sometimes indicated by the prefix n- (for normal) for a non-linear isomer exists. Although this is not strictly necessary, the usage is still common in cases where there is an important difference in properties between the straight-chain and branched-chain isomers.

The members of the series (in terms of number of silicon atoms) are named as follows:

- silane, SiH

4 - one silicon and four hydrogen - disilane, Si

2H

6 - two silicon and six hydrogen - trisilane, Si

3H

8 - three silicon and 8 hydrogen - tetrasilane, Si

4H

10 - four silicon and 10 hydrogen - pentasilane, Si

5H

12 - five silicon and 12 hydrogen

Silanes are named by adding the suffix -silane to the appropriate numerical multiplier prefix. Hence, disilane, Si

2H

6; trisilane Si

3H

8; tetrasilane Si

4H

10; pentasilane Si

5H

12; etc. The prefix is generally Greek, with the exceptions of nonasilane which has a Latin prefix, and undecasilane and tridecasilane which have mixed-language prefixes.

Branched silanes

Simple branched silanes often have a common name using a prefix to distinguish them from linear silanes, for example n-pentasilane, isopentasilane, and neopentasilane.

IUPAC naming conventions can be used to produce a systematic name.

The key steps in the naming of more complicated branched silanes are as follows:

- Identify the longest continuous chain of silicon atoms

- Name this longest root chain using standard naming rules

- Name each side chain by changing the suffix of the name of the silane from "-ane" to "-anyl", except for "silane" which becomes "silyl"

- Number the root chain so that the sum of the numbers assigned to each side group will be as low as possible

- Number and name the side chains before the name of the root chain

The nomenclature parallels that of alkyl radicals.

Silanes can also be named like any other inorganic compound; in this naming system, silane is named silicon tetrahydride. However, with longer silanes, this becomes cumbersome.

Circular structures, called cyclosilanes, also exist. These are analogous to the cycloalkanes. Solid phase polymeric silicon hydrides called polysilicon hydrides are also known. When hydrogen in a linear polysilene polysilicon hydride is replaced with alkyl or aryl side-groups, the term polysilane is used.

Unsaturated silicon hydride molecules called silenes contain the trivalent (doubly-bonded) silicon atom, >Si= (e.g. methylene silane or silaethene, H2Si(CH2)). They cannot be isolated under normal conditions. The silylenes contain the divalent Si atom (e.g. SiH2, SiF2). Most silylenes are unstable at normal temperatures and can only be synthesized in the gas phase at elevated temperatures or isolated in a low-temperature matrix.

Physical properties

Table of silanes

| Silane | Formula | Boiling point [°C] | Melting point [°C] | Density [g cm−3] (at 25 °C) |

| Silane | SiH 4 |

-112 | -185 | gas |

| Disilane | Si 2H 6 |

-14 | -132 | gas |

| Trisilane | Si 3H 8 |

53 | -117 | 0.743 (liquid) |

| Tetrasilane | Si 4H 10 |

100 | -84 | liquid |

Boiling point

Silanes experience inter-molecular van der Waals forces. Stronger inter-molecular van der Waals forces give rise to greater boiling points of silanes.

There are two determinants for the strength of the van der Waals forces:

- the number of electrons surrounding the molecule, which increases with the silane's molecular weight

- the surface area of the molecule

Under standard conditions, SiH

4 and Si

2H

6 silanes are gaseous; Si

3H

8 and Si

4H

10 are liquids. As the boiling point of silanes is primarily determined by weight, it should not be a surprise that the boiling point has almost a linear relationship with the size (molecular weight) of the molecule.

A straight-chain silane will have a boiling point higher than a branched-chain silane due to the greater surface area in contact, thus the greater van der Waals forces, between adjacent molecules.

On the other hand, cyclosilane tend to have higher boiling points than their linear counterparts due to the locked conformations of the molecules, which give a plane of intermolecular contact.

Melting point

The melting points of the silanes follow a similar trend to boiling points for the same reason as outlined above. That is, (all other things being equal) the larger the molecule the higher the melting point. There is one significant difference between boiling points and melting points. Solids have more rigid and fixed structure than liquids. This rigid structure requires energy to break down. Thus the better put together solid structures will require more energy to break apart. The odd-numbered silanes have a lower trend in melting points than even numbered silanes. This is because even numbered silanes pack well in the solid phase, forming a well-organized structure, which requires more energy to break apart. The odd-number silanes pack less well and so the "looser" organized solid packing structure requires less energy to break apart.

The melting points of branched-chain silanes can be either higher or lower than those of the corresponding straight-chain silanes, again depending on the ability of the silane in question to pack well in the solid phase: This is particularly true for isosilanes (2-silyl isomers), which often have melting points higher than those of the linear analogues.

Conductivity and solubility

Silanes do not conduct electricity, nor are they substantially polarised by an electric field. For this reason they do not form hydrogen bonds and are insoluble in polar solvents such as water. Since the hydrogen bonds between individual water molecules are aligned away from a silane molecule, the coexistence of a silane and water leads to an increase in molecular order (a reduction in entropy). As there is no significant bonding between water molecules and silane molecules, the second law of thermodynamics suggests that this reduction in entropy should be minimized by minimizing the contact between silane and water: Silanes are said to be hydrophobic in that they repel water.

Their solubility in nonpolar solvents is relatively good, a property that is called lipophilicity. Different silanes are, for example, miscible in all proportions among themselves.

The density of the silanes usually increases with increasing number of silicon atoms, but remains less than that of water. Hence, silanes form the upper layer in an silane-water mixture.

Molecular geometry

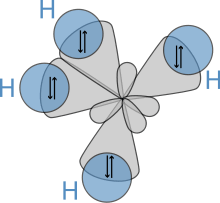

The molecular structure of the silanes directly affects their physical and chemical characteristics. It is derived from the electron configuration of silicon, which has four valence electrons. The silicon atoms in silanes are always sp3 hybridised, that is to say that the valence electrons are said to be in four equivalent orbitals derived from the combination of the 3s orbital and the three 3p orbitals. These orbitals, which have identical energies, are arranged spatially in the form of a tetrahedron, the angle of  between them.

between them.

Bond lengths and bond angles

A silane molecule has only Si – H and Si – Si single bonds. The former result from the overlap of a sp³-orbital of silicon with the 1s-orbital of a hydrogen; the latter by the overlap of two sp³-orbitals on different silicon atoms. The bond lengths amount to 146.0 pm for a Si – H bond and 233 pm for a Si – Si bond.

The spatial arrangement of the bonds is similar to that of the four sp³-orbitals—they are tetrahedrally arranged, with an angle of 109.47° between them. Structural formulae that represent the bonds as being at right angles to one another, while both common and useful, do not correspond with the reality.

Chemical properties

The silanes (SinH2n+2) are much less thermally stable than alkanes (CnH2n+2) and they are kinetically labile, with their decomposition reaction rate increasing with increases in the number of silicon atoms in the molecule. This makes preparation and isolation of SinH2n+2 molecules with n greater than about 8 difficult.[3] Greater catenation of the Si atoms can be obtained with the halides (SinX2n+2 with n = 14 for the fluorides) because of pi back bonding from the halogen p orbitals to the Si d orbitals, which compensates for the electron withdrawal from Si towards the halogen that occurs through the sigma bonding.[4]

Silanes can also incorporate the same functional groups as alkanes, e.g. –OH, to make a silanol (an analogue of alcohol) or a halogen to make a silicon halide (an analogue of alkyl halide). There is (in principle) a silicon analogue for all carbon alkanes derivatives. Like carbon, there also exists silicocations, an important class is the silanyliums, of which simplest member is the silylium ion (SiH+

3).

Production

Schlesinger

The Schlesinger process is a method to synthesise liquid silanes, from perchlorosilanes and lithium tetrahydridoaluminate(-1).

Laboratory preparation

There is usually little need for silanes to be synthesised in the laboratory, since they are usually commercially available. Silanes are generally reactive chemically and biologically, but do not undergo functional group interconversions cleanly. When silanes are produced in the laboratory, it is often a side-product of a reaction. For example, the use magnesium silicide as a base gives the conjugate acids, mixed silanes as a side-product.

In general, the alkaline-earth metals form silicides with various stoichiometry. However, in all cases these substances react with Brønsted–Lowry acids to produce some type of hydride of silicon that is dependent on the Si anion connectivity in the silicide. The possible products include silane and/or higher molecules in the homologous series, a polymeric silicon hydride, or a silicic acid. Hence, MSi with their zigzag chains of Si anions (containing two lone pairs of electrons on each Si anion that can accept protons) yield the polymeric hydride (SiH2)x.

However, at times it may be desirable to make a portion of a molecule into a silane like functionality (silanyl group) using the above or similar methods.

Applications

Several industrial and medical applications exist for the simplest silane (SiH4) and functionalized silanes. For instance, silanes are used as coupling agents to adhere glass fibers to a polymer matrix, stabilizing the composite material. They can also be used to couple a bio-inert layer on a titanium implant. Other applications include water repellents, masonry protection, control of graffiti,[5] applying polycrystalline silicon layers on silicon wafers when manufacturing semiconductors, and sealants.

Silane (SiH4) and similar compounds containing Si—H bonds are used as reducing agents in organic and organometallic chemistry.[6]

“Magic sand” exposes regular sand to trimethylhydroxysilane vapors to make the sand waterproof.

Hazards

Silane is explosive when mixed with air (1 – 98% SiH4). Other lower silanes can also form explosive mixtures with air. The lighter liquid silanes are highly flammable, this risk increases with the length of the silicon chain.

Considerations for detection/risk control:

- Silane is slightly heavier than air (possibility of pooling at ground levels/pits)

- Disilane is heavier than air (possibility of pooling at ground levels/pits)

- Trisilane is heavier than air (possibility of pooling at ground levels/pits)

Subclasses of silane

There are many structural analogues of silane, which do not necessarily contain an organic functional group. These include classes such as fluorosilanes, silanamines, silanols, silanones.

Halosilanes

Chlorosilane examples:

Other halosilanes:

Mixed halosilanes:

- Chlorotrifluorosilane

- Dichlorodifluorosilane

- Trichlorofluorosilane

Organosilanes

The organosilanes are a group of chemical compounds derived from silanes containing one or more organic groups. They are a subset of the general class of organosilicons, although the distinction is not often made. 'Organosilanes' has subsets of its own, such as organosilanols, organosilanones, and so forth.

Alkylsilane examples:

- Methylsilane

- 3-(Trimethylsilyl)propanoic acid

- Trimethyl(trifluoromethyl)silane

- Trimethylsilanecarbonitrile

- Dialkylsilane examples:

- Polyalkylsilane examples:

Organochlorosilane examples:

- Organodichlorosilane examples:

- Organopolychlorosilane examples:

Oxalkylsilanes examples:

- Diethoxydimethylsilane

- Triethoxysilane

- (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane

- Trimethoxy(octadecyl)silane

- Tetramethyl silicate

- Tetraethyl silicate

Other examples:

- Ethenylsilane

- Trimethylsilanol (an example of an organosilanol)

- Tris(tert-butoxy)silanethiol (an example of an organosilanethiol)

- Iodotrimethylsilane (an example of an organoiodosilane)

- ethynyltrimethylsilane

Heterosilanes

An important, class of silicon compounds that is parallel to silanes, are the heterosilanes. The heterosilanes describes silanes, where one or more non-terminal silicon atoms are substituted with an atom of a different element. This gives rise to various subsets, such as siloxanes, silazanes, silathianes, and so forth. (Silyloxy)silane is the simplest example of a siloxane.

Organoheterosilanes

Organoheterosilanes are perhaps the most important, and widely used, subclass of chemical compounds belonging to heterosilane class. This class contains silicones, which are compounds based on siloxane polymers.

Organooxasilane examples:

- Trimethyl[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]silane

- 2-(2H-1,2,3-benzotriazol-2-yl)-4-methyl-6-[2-methyl-3-(2,2,4,6,6-pentamethyl-3,5-dioxa-2,4,6-trisilaheptan-4-yl)propyl]phenol

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silanes. |

References

- ↑ E. Wiber, Alfred Stock and the Renaissance of Inorganic Chemistry," Pure & Appl. Chem., Vol. 49 (1977) pp. 691-700.

- ↑ J. W. Mellor, "A Comprehensive Treatise on Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry," Vol. VI, Longman, Green and Co. (1947) pp. 223 - 227.

- ↑ W. W. Porterfield "Inorganic Chemistry: A Unified Approach," Academic Press (1993) p. 219.

- ↑ A. Earnshaw, N. Greenwood, "Chemistry of the Elements," Butterworth-Heinemnann (1997) p. 341.

- ↑ Graffiti protection systems

- ↑ Reductions of organic compounds using silanes