Sichuan

| Sichuan Province 四川省 | |

|---|---|

| Province | |

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | 四川省 (Sìchuān Shěng) |

| • Abbreviation |

川 or 蜀 (pinyin: Chuān or Shǔ Sichuanese: Cuan1 or Su2) |

| • Sichuanese | Si4cuan1 Sen3 |

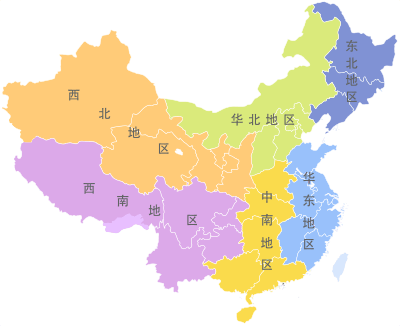

.svg.png) Map showing the location of Sichuan Province | |

| Coordinates: 30°08′N 102°56′E / 30.133°N 102.933°ECoordinates: 30°08′N 102°56′E / 30.133°N 102.933°E | |

| Named for |

Short for 川峡四路 chuānxiá sìlù literally "The Four Circuits of the Rivers and Gorges", referring to the four circuits during the Song dynasty |

| Capital (and largest city) | Chengdu |

| Divisions | 21 prefectures, 181 counties, 5011 townships |

| Government | |

| • Secretary | Wang Dongming |

| • Governor | Wei Hong |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 485,000 km2 (187,000 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 5th |

| Population (2013)[2] | |

| • Total | 81,100,000 |

| • Rank | 4th |

| • Density | 170/km2 (430/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 22nd |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition |

Han - 95% Yi - 2.6% Tibetan - 1.5% Qiang - 0.4% |

| • Languages and dialects | Southwestern Mandarin (Sichuanese Mandarin), Khams Tibetan |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-51 |

| GDP (2014) |

CNY 2.854 trillion US$ 464.5 billion (9th) |

| - per capita |

CNY 35,187 US$ 5,728 (25th) |

| HDI (2010) | 0.662[3] (medium) (23rd) |

| Website |

www |

| Sichuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 四川 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanyu Pinyin | Sìchuān | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sichuanese Pinyin | Si4cuan1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal Map | Szechwan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sichuan (Chinese: 四川; pinyin: ![]() Sìchuān, known formerly in the West by its postal map romanization of Szechwan or the alternative romanisation Szechuan) is a province in southwest China. The name of the province is an abbreviation of Sì Chuānlù (四川路), or "Four circuits of rivers", which is itself abbreviated from Chuānxiá Sìlù (川峡四路), or "Four circuits of rivers and gorges", named after the division of the existing circuit into four during the Northern Song dynasty.[4] The capital is Chengdu, a key economic centre of Western China.

Sìchuān, known formerly in the West by its postal map romanization of Szechwan or the alternative romanisation Szechuan) is a province in southwest China. The name of the province is an abbreviation of Sì Chuānlù (四川路), or "Four circuits of rivers", which is itself abbreviated from Chuānxiá Sìlù (川峡四路), or "Four circuits of rivers and gorges", named after the division of the existing circuit into four during the Northern Song dynasty.[4] The capital is Chengdu, a key economic centre of Western China.

History

Ba-Shu Kingdoms

Throughout its prehistory and early history, the region and its vicinity in the Yangtze region was the cradle of unique local civilizations which can be dated back to at least the 15th century BC and coinciding with the later years of the Shang and Zhou dynasties in North China. Sichuan was referred to in ancient Chinese sources as Ba-Shu (巴蜀), an abbreviation of the kingdoms of Ba and Shu which existed within the Sichuan Basin. Ba included Chongqing and the land in eastern Sichuan along the Yangtze and some tributary streams, while Shu included today's Chengdu, its surrounding plain and adjacent territories in western Sichuan.[5]

The existence of the early state of Shu was poorly recorded in the main historical records of China. It was, however, referred to in the Book of Documents as an ally of the Zhou.[6] Accounts of Shu exist mainly as a mixture of mythological stories and historical legends recorded in local annals such as the Chronicles of Huayang compiled in the Jin dynasty (265–420),[7][8] with folk stories such as that of Emperor Duyu (杜宇) who taught the people agriculture and transformed himself into a cuckoo after his death.[9] The existence of a highly developed civilization with an independent bronze industry in Sichuan eventually came to light with an archaeological discovery in 1986 at a small village named Sanxingdui in Guanghan, Sichuan.[9] This site, believed to be an ancient city of Shu, was initially discovered by a local farmer in 1929 who found jade and stone artefacts. Excavations by archaeologists in the area yielded few significant finds until 1986 when two major sacrificial pits were found with spectacular bronze items as well as artefacts in jade, gold, earthenware, and stone.[10] This and other discoveries in Sichuan contest the conventional historiography that the local culture and technology of Sichuan were undeveloped in comparison to the technologically and culturally "advanced" Yellow River valley of north-central China.

The region had its own distinct religious beliefs and worldview. Various ores were abundant. Adding to its significance, the area was also on the trade route from the Yellow River valley to foreign countries of the southwest, especially India.

Qin Dynasty

The rulers of the expansionist Qin dynasty, based in present day Gansu and Shaanxi, were only the first strategists to realize that the area's military importance matched its commercial and agricultural significance. The Sichuan basin is surrounded by the Himalayas to the west, the Qin Mountains to the north, and mountainous areas of Yunnan to the south. Since the Yangtze flows through the basin and then through the perilous Yangzi Gorges to eastern and southern China, Sichuan was a staging area for amphibious military forces and a refuge for political refugees.

Qin armies finished their conquest of the kingdoms of Shu and Ba by 316 BC. Any written records and civil achievements of earlier kingdoms were destroyed. Qin administrators introduced improved agricultural technology. Li Bing, engineered the Dujiangyan irrigation system to control the Min River, a major tributary of the Yangtze. This innovative hydraulic system was composed of movable weirs which could be adjusted for high or low water flow according to the season, to either provide irrigation or prevent floods. The increased agricultural output and taxes made the area a source of provisions and men for Qin's unification of China.

Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms

Sichuan was subjected to the autonomous control of kings named by the imperial family of Han Dynasty. Following the declining central government of the Han dynasty in the second century, the Sichuan basin, surrounded by mountains and easily defensible, became a popular place for upstart generals to found kingdoms that challenged the authority of Yangtze Valley emperors over China.[11]

In 221, during the partition following the fall of the Eastern Han - the era of the Three Kingdoms - Liu Bei founded the southwest kingdom of Shu Han (蜀汉; 221-263) in parts of Sichuan, Guizhou and Yunnan, with Chengdu as its capital. Shu-Han claimed to be the successor to the Han Dynasty.[11]

In 263, the Jin dynasty of North China, conquered the Kingdom of Shu-Han as its first step on the path to unify China again, under their rule. Salt production becomes a major business in Ziliujing District. During this Six Dynasties period of Chinese disunity, Sichuan began to be populated by non-Han ethnic minority peoples, owing to the migration of Gelao people from the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the Sichuan basin, where the Han are indigenous.

Tang Dynasty

Sichuan came under the firm control of a Chinese central government during the Sui dynasty, but it was during the subsequent Tang dynasty where Sichuan regained its previous political and cultural prominence for which it was known during the Han. Chengdu became nationally known as a supplier of armies and the home of Du Fu, who is sometimes called China's greatest poet. During the An Lushan Rebellion (755-763), Emperor Xuanzong of Tang fled from Chang'an to Sichuan. The region was torn by constant warfare and economic distress as it was besieged by the Tibetan Empire.[12]

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms

In the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, Sichuan became the centre of the Shu kingdom with its capital in Chengdu founded by Wang Jian. In 925 the kingdom was absorbed into Later Tang but would regain independence under Meng Zhixiang who founded Later Shu in 934. Later Shu would continue until 965 when it was absorbed by the Song.

Song Dynasty

The next strongly centralized government of China, the Song dynasty (960-1279), was able to protect Sichuan from Tibetan attacks and the region saw a cultural revival with the literary works of Su Xun (蘇洵), Su Shi, and Su Zhe.[12]

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Southern Song Dynasty established coordinated defenses against the Mongolian Yuan dynasty, in Sichuan and Xiangyang. The Southern Song state monopolized the Sichuan tea industry to pay for warhorses, but this state intervention eventually brought devastation to the local economy.[13] The line of defense was finally broken through after the first use of firearms in history during the six-year Battle of Xiangyang, which ended in 1273.

Ming Dynasty

During the Ming dynasty, major architectural works were created in Sichuan. Buddhism remained influential in the region. Bao'en Temple is a well-preserved 15th century monastery complex built between 1440 and 1446 during the Zhengtong Emperor's reign (1427–64). Dabei Hall enshrines a thousand-armed wooden image of Guanyin and Huayan Hall is a repository with a revolving sutra cabinet. The wall paintings, sculptures and other ornamental details are masterpieces of the Ming period.[14]

In the middle of the 17th century, the peasant rebel leader Zhang Xianzhong(1606–1646) from Yan'an, Shanxi Province, nicknamed Yellow Tiger, led his peasant troop from north China to the south, and conquered Sichuan. Upon capturing it, he declared himself emperor of the Daxi Dynasty (大西王朝). In response to the resistance from local elites, he massacred a large native population.[15] As a result of the massacre as well as the years of turmoil after the Ming-Qing transition, the population of Sichuan fell sharply, requiring a massive resettlement of people from neighboring Huguang Province (modern Hubei and Hunan).[16][17]

Qing Dynasty

During the Qing dynasty, Sichuan was merged with Shaanxi and Shanxi to create "Shenzhuan" from 1680-1731 and 1735-1748.[12] The current borders of Sichuan (which then included Chongqing) were established in the early 18th century. In the aftermath of the Sino-Nepalese War on China's southwestern border, the Qing gave Sichuan's provincial government direct control over the minority-inhabited areas of Sichuan west of Kangding, which had previously been handled by an amban.[17]

A landslide dam on the Dadu River caused by an earthquake gave way on 10 June 1786. The resulting flood killed 100,000 people.[18]

Republic of China

In the early 20th century, the newly founded Republic of China established Chuanbian Special Administrative District (川邊特別行政區), which acknowledged the unique culture and economy of the region largely differing from that of mainstream northern China in the Yellow River region. The Special District later became the province of Xikang, incorporating the areas inhabited by Yi, Tibetan and Qiang ethnic minorities to its west, and eastern part of today's Tibet Autonomous Region.

In the 20th century, as Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Wuhan had all been occupied by the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the capital of the Republic of China had been temporary relocated to Chongqing, then a major city in Sichuan. An enduring legacy of this move is that nearby inland provinces, such as Shaanxi, Gansu, and Guizhou, which previously never had modern Western-style universities, began to be developed in this regard.[19] The difficulty of accessing the region overland from the eastern part of China and the foggy climate hindering the accuracy of Japanese bombing of the Sichuan Basin, made the region the stronghold of Chiang Kai-Shek's Kuomintang government during 1938-45, and led to the Bombing of Chongqing.

The Second Sino-Japanese War was soon followed by the resumed Chinese Civil War, and the cities of East China fell to the Communists one after another, the Kuomintang government again tried to make Sichuan its stronghold on the mainland, although it already saw some Communist activity since it was one area on the road of the Long March. Chiang Kai-Shek himself flew to Chongqing from Taiwan in November 1949 to lead the defense. But the same month Chongqing fell to the Communists, followed by Chengdu on 10 December. The Kuomintang general Wang Sheng wanted to stay behind with his troops to continue anticommunist guerilla war in Sichuan, but was recalled to Taiwan. Many of his soldiers made their way there as well, via Burma.[20]

People's Republic of China

The People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, and it split Sichuan into four areas and separated out Chongqing municipality. Sichuan was reconstituted in 1952, with Chongqing added in 1954, while the former Xikang province was split between Tibet in the west and Sichuan in the east.[12]

The province was deeply affected by the Great Chinese Famine of 1959-1961, during which period some 9.4 million people (13.07% of the population at the time) died.[21]

In 1978, when Deng Xiaoping took power, Sichuan was one of the first provinces to undergo limited experimentation with market economic enterprise.

From 1955 until 1997 Sichuan had been China's most populous province, hitting 100 million mark shortly after the 1982 census figure of 99,730,000.[22] This changed in 1997 when the city of Chongqing as well as the surrounding counties of Fuling and Wanxian were split off into the new Chongqing Municipality. The new municipality was formed to spearhead China's effort to economically develop its western provinces, as well as to coordinate the resettlement of residents from the reservoir areas of the Three Gorges Dam project.

In 1997 when Sichuan split, the sum of the two parts was recorded to be 114,720,000 people.[23] As of 2010, Sichuan ranks as both the 3rd largest and 4th most populous province in China.[24]

In May 2008, an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.9/8.0 hit just 79 kilometres (49 mi) northwest of the provincial capital of Chengdu. Official figures recorded a death toll of nearly 70,000 people, and millions of people were left homeless.[25]

Administrative divisions

Sichuan consists of twenty-one prefecture-level divisions: eighteen prefecture-level cities (including a sub-provincial city) and three autonomous prefectures:

| Map | # | Name | Administrative Seat | Chinese Hanyu Pinyin |

Population (2010) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| — Sub-provincial city — | |||||

| 9 | Chengdu (Provincial seat) |

Qingyang District | 成都市 Chéngdū Shì |

14,047,625 | |

| — Prefecture-level city — | |||||

| 3 | Mianyang | Fucheng District | 绵阳市 Miányáng Shì |

4,613,862 | |

| 4 | Guangyuan | Lizhou District | 广元市 Guǎngyuán Shì |

2,484,125 | |

| 5 | Nanchong | Shunqing District | 南充市 Nánchōng Shì |

6,278,622 | |

| 6 | Bazhong | Bazhou District | 巴中市 Bāzhōng Shì |

3,283,771 | |

| 7 | Dazhou | Tongchuan District | 达州市 Dázhōu Shì |

5,468,092 | |

| 8 | Ya'an | Yucheng District | 雅安市 Yǎ'ān Shì |

1,507,264 | |

| 10 | Deyang | Jingyang District | 德阳市 Déyáng Shì |

3,615,759 | |

| 11 | Suining | Chuanshan District | 遂宁市 Suìníng Shì |

3,252,551 | |

| 12 | Guang'an | Guang'an District | 广安市 Guǎng'ān Shì |

3,205,476 | |

| 13 | Meishan | Dongpo District | 眉山市 Méishān Shì |

2,950,548 | |

| 14 | Ziyang | Yanjiang District | 资阳市 Zīyáng Shì |

3,665,064 | |

| 15 | Leshan | Shizhong District | 乐山市 Lèshān Shì |

3,235,756 | |

| 16 | Neijiang | Shizhong District | 内江市 Nèijiāng Shì |

3,702,847 | |

| 17 | Zigong | Ziliujing District | 自贡市 Zìgòng Shì |

2,678,898 | |

| 18 | Yibin | Cuiping District | 宜宾市 Yíbīn Shì |

4,472,001 | |

| 19 | Luzhou | Jiangyang District | 泸州市 Lúzhōu Shì |

4,218,426 | |

| 21 | Panzhihua | Dongqu District | 攀枝花市 Pānzhīhuā Shì |

1,214,121 | |

| — Autonomous prefectures — | |||||

| 1 | Garzê (for Tibetan) |

Kangding | 甘孜藏族自治州 Gānzī Zàngzú Zìzhìzhōu |

1,091,872 | |

| 2 | Ngawa (for Tibetan & Qiang) |

Barkam County Barkam |

阿坝藏族羌族自治州 Ābà Zàngzú Qiāngzú Zìzhìzhōu |

898,713 | |

| 20 | Liangshan (for Yi) |

Xichang | 凉山彝族自治州 Liángshān Yízú Zìzhìzhōu |

4,532,809 | |

Geography

Sichuan consists of two geographically very distinct parts. The eastern part of the province is mostly within the fertile Sichuan basin (which is shared by Sichuan with Chongqing Municipality). The western Sichuan consists of the numerous mountain ranges forming the easternmost part of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, which are known generically as Hengduan Mountains. One of these ranges, Daxue Mountains, contains the highest point of the province Gongga Shan, at 7,556 metres (24,790 ft) above sea level.

Lesser mountain ranges surround the Sichuan Basin from north, east, and south. Among them are the Daba Mountains, in the province's northeast.

Plate tectonics formed the Longmen Shan fault, which runs under the north-easterly mountain location of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake.

The Yangtze River and its tributaries flows through the mountains of western Sichuan and the Sichuan Basin; thus, the province is upstream of the great cities that stand along the Yangtze River further to the east, such as Chongqing, Wuhan, Nanjing and Shanghai. One of the major tributaries of the Yangtze within the province is the Min River of central Sichuan, which joins the Yangtze at Yibin. Sichuan's 4 main rivers, as Sichuan means literally, are Jaling Jiang, Tuo Jiang, Yalong Jiang, and Jinsha Jiang.

Due to great differences in terrain, the climate of the province is highly variable. In general it has strong monsoonal influences, with rainfall heavily concentrated in the summer. Under the Köppen climate classification, the Sichuan Basin (including Chengdu) in the eastern half of the province experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa or Cfa), with long, hot, humid summers and short, mild to cool, dry and cloudy winters. Consequently, it has China's lowest sunshine totals. The western region has mountainous areas producing a cooler but sunnier climate. Having cool to very cold winters and mild summers, temperatures generally decrease with greater elevation. However, due to high altitude and its inland location, many areas such as Garze County and Zoige County in Sichuan exhibit a subarctic climate (Köppen Dwc)- featuring extremely cold winters down to -30°C and even cold summer nights. The region is geologically active with landslides and earthquakes. Average elevation ranges from 2,000 to 3,500 meters; average temperatures range from 0 to 15 °C.[26] The southern part of the province, including Panzhihua and Xichang, has a sunny climate with short, very mild winters and very warm to hot summers.

Sichuan borders Qinghai to the northwest, Gansu to the north, Shaanxi to the northeast, Chongqing to the east, Guizhou to the southeast, Yunnan to the south, and the Tibet Autonomous Region to the west.

-

Larix potaninii in autumn colour.

-

Jiuzhaigou Valley

-

Garzê Prefecture

Politics

The politics of Sichuan is structured in a dual party-government system like all other governing institutions in mainland China.

The Governor of Sichuan is the highest-ranking official in the People's Government of Sichuan. However, in the province's dual party-government governing system, the Governor has less power than the Sichuan Communist Party of China Provincial Committee Secretary, colloquially termed the "Sichuan CPC Party Chief".

Economy

Sichuan has been historically known as the "Province of Abundance". It is one of the major agricultural production bases of China. Grain, including rice and wheat, is the major product with output that ranked first in China in 1999. Commercial crops include citrus fruits, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, peaches and grapes. Sichuan also had the largest output of pork among all the provinces and the second largest output of silkworm cocoons in 1999. Sichuan is rich in mineral resources. It has more than 132 kinds of proven underground mineral resources including vanadium, titanium, and lithium being the largest in China. The Panxi region alone possesses 13.3% of the reserves of iron, 93% of titanium, 69% of vanadium, and 83% of the cobalt of the whole country.[27] Sichuan also possesses China's largest proven natural gas reserves, the majority of which is transported to more developed eastern regions.[24]

Sichuan is one of the major industrial centers of China. In addition to heavy industries such as coal, energy, iron and steel, the province has also established a light industrial sector comprising building materials, wood processing, food and silk processing. Chengdu and Mianyang are the production centers for textiles and electronics products. Deyang, Panzhihua, and Yibin are the production centers for machinery, metallurgical industries, and wine, respectively. Sichuan's wine production accounted for 21.9% of the country’s total production in 2000.

Great strides have been made in developing Sichuan into a modern hi-tech industrial base, by encouraging both domestic and foreign investments in electronics and information technology (such as software), machinery and metallurgy (including automobiles), hydropower, pharmaceutical, food and beverage industries.

The auto industry is an important and key sector of the machinery industry in Sichuan. Most of the auto manufacturing companies are located in Chengdu, Mianyang, Nanchong, and Luzhou.[28]

Other important industries in Sichuan include aerospace and defense (military) industries. A number of China's rockets (Long March rockets) and satellites were launched from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center, located in the city of Xichang.

Sichuan's beautiful landscapes and rich historical relics have also made the province a major center for tourism.

The Three Gorges Dam, the largest dam ever constructed, is being built on the Yangtze River in nearby Hubei province to control flooding in the Sichuan Basin, neighboring Yunnan province, and downstream. The plan is hailed by some as China's efforts to shift towards alternative energy sources and to further develop its industrial and commercial bases, but others have criticised it for its potentially harmful effects, such as massive resettlement of residents in the reservoir areas, loss of archeological sites, and ecological damages.

Sichuan's nominal GDP for 2011 was 2.15 trillion yuan (US$340 billion), equivalent to 17,380 RMB (US$2,545) per capita.[29] In 2008, the per capita net income of rural residents was 4,121 yuan (US$593), up 16.2% from 2007. The per capita disposable income of the urbanites averaged 12,633 yuan (US$1,819), up 13.8% from 2007.[30][31]

Foreign trade

According to the Sichuan Department of Commerce, the province's total foreign trade was US$22.04 billion in 2008, with an annual increase of 53.3 percent. Exports were US$13.1 billion, an annual increase of 52.3 percent, while imports were US$8.93 billion, an annual increase of 54.7 percent. These achievements were accomplished because of significant changes in China's foreign trade policy, acceleration of the yuan's appreciation, increase of commercial incentives and increase in production costs. The 18 cities and counties witnessed a steady rate of increase. Chengdu, Suining, Nanchong, Dazhou, Ya'an, Abazhou, and Liangshan all saw an increase of more than 40 percent while Leshan, Neijiang, Luzhou, Meishan, Ziyang, and Yibin saw an increase of more than 20 percent. Foreign trade in Zigong, Panzhihua, Guang'an, Bazhong and Ganzi remained constant.

Minimum wage

The Sichuan government raised the minimum wage in the province by 12.5 percent at the end of December 2007. The monthly minimum wage went up from 400 to 450 yuan, with a minimum of 4.9 yuan per hour for part-time work, effective December 26, 2007. The government also reduced the four-tier minimum wage structure to three. The top tier mandates a minimum of 650 yuan per month, or 7.1 yuan per hour. National law allows each province to set minimum wages independently, but with a floor of 450 yuan per month.

Economic and technological development zones

Chengdu Economic and Technological Development Zone

Chengdu Economic and Technological Development Zone (Chinese: 成都经济技术开发区; pinyin: Chéngdū jīngjì jìshù kāifā qū) was approved as state-level development zone in February 2000. The zone now has a developed area of 10.25 km2 (3.96 sq mi) and has a planned area of 26 km2 (10 sq mi). Chengdu Economic and Technological Development Zone (CETDZ) lies 13.6 km (8.5 mi) east of Chengdu, the capital city of Sichuan Province and the hub of transportation and communication in southwest China. The zone has attracted investors and developers from more than 20 countries to carry out their projects there. Industries encouraged in the zone include mechanical, electronic, new building materials, medicine and food processing.[32]

Chengdu Export Processing Zone

Chengdu Export Processing Zone ((Chinese: 成都出口加工区; pinyin: Chéngdū chūkǒu jiāgōng qū)) was ratified by the State Council as one of the first 15 export processing zones in the country in April 2000. In 2002, the state ratified the establishment of the Sichuan Chengdu Export Processing West Zone with a planned area of 1.5 km2 (0.58 sq mi), located inside the west region of the Chengdu Hi-tech Zone.[33]

Chengdu Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

Established in 1988, Chengdu Hi-tech Industrial Development Zone (Chinese: 成都高新技术产业开发区; pinyin: Chéngdū Gāoxīn Jìshù Chǎnyè Kāifā Qū) was approved as one of the first national hi-tech development zones in 1991. In 2000, it was open to APEC and has been recognized as a national advanced hi-tech development zone in successive assessment activities held by China's Ministry of Science and Technology. It ranks 5th among the 53 national hi-tech development zones in China in terms of comprehensive strength.

Chengdu Hi-tech Development Zone covers an area of 82.5 km2 (31.9 sq mi), consisting of the South Park and the West Park. By relying on the city sub-center, which is under construction, the South Park is focusing on creating a modernized industrial park of science and technology with scientific and technological innovation, incubation R&D, modern service industry and Headquarters economy playing leading roles. Priority has been given to the development of software industry. Located on both sides of the "Chengdu-Dujiangyan-Jiuzhaigou" golden tourism channel, the West Park aims at building a comprehensive industrial park targeting at industrial clustering with complete supportive functions. The West Park gives priority to three major industries i.e. electronic information, biomedicine and precision machinery.[34]

-

Hongzhaobi, South Renmin Road, Chengdu

-

South Renmin Road, Chengdu

-

Hongxing Road, Chengdu

-

Zongfu Road, Shudu Ave., Chengdu

-

Nijia Qiao, South Renmin Road, Chengdu

-

Jin River, Shangri-la Hotel Chengdu

Mianyang Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

Mianyang Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone was established in 1992, with a planned area of 43 km2 (17 sq mi). The zone is situated 96 kilometers away from Chengdu, and is 8 km (5.0 mi) away from Mianyang Airport. Since its establishment, the zone accumulated 177.4 billion yuan of industrial output, 46.2 billion yuan of gross domestic product, fiscal revenue 6.768 billion yuan. There are more than 136 high-tech enterprises in the zone and they accounted for more than 90% of the total industrial output.

The zone is a leader in the electronic information industry, biological medicine, new materials and production of motor vehicles and parts.[35]

Transportation

For millennia, Sichuan's rugged and riverine landscape presented enormous challenges to the development of transportation infrastructure, and the lack of roads out of the Sichuan Basin contributed to the region's isolation. Since the 1950s, numerous highways and railways have been built through the Qinling in the north and the Bashan in the east. Dozens of bridges across the Yangtze and its tributaries to the south and west have brought greater connectivity with Yunnan and Tibet.

Expressways

On 3 November 2007, the Sichuan Transportation Bureau announced that the Sui-Yu Expressway was completed after three years of construction. After completion of the Chongqing section of the road, the 36.64 km (22.77 mi) expressway connected Cheng-Nan Expressway and formed the shortest expressway from Chengdu to Chongqing. The new expressway is 50 km (31 mi) shorter than the pre-existing road between Chengdu and Chongqing; thus journey time between the two cities was reduced by an hour, now taking two and a half hours. The Sui-Yu Expressway is a four lane overpass with a speed limit of 80 km/h (50 mph). The total investment was 1.045 billion yuan.

Rail

Major railways in Sichuan include the Baoji–Chengdu, Chengdu–Chongqing, Chengdu–Kunming, Neijiang–Kunming, Suining-Chongqing and Chengdu–Dazhou Railways. A high-speed rail line connects Chengdu and Dujiangyan.

Demographics

The majority of the province's population is Han Chinese, who are found scattered throughout the region with the exception of the far western areas. Thus, significant minorities of Tibetans, Yi, Qiang and Naxi reside in the western portion that are impacted by inclement weather and natural disasters, environmentally fragile, and impoverished. Sichuan's capital of Chengdu is home to a large community of Tibetans, with 30,000 permanent Tibetan residents and up to 200,000 Tibetan floating population.[36] The Eastern Lipo, included with either Yi people or Lisu people as well as the A-Hmao also are among the ethnic groups of the provinces.

Sichuan was China's most populous province before Chongqing became a directly-controlled municipality; it is currently the fourth most populous, after Guangdong, Shandong and Henan. As of 1832, Sichuan was the most populous of the 18 provinces in China, with an estimated population at that time of 21 million.[37] It was the third most populous sub-national entity in the world, after Uttar Pradesh, India and the Russian SFSR until 1991 when the Soviet Union was dissolved. It is also one of the only six to ever reach 100 million people (Uttar Pradesh, Russian RSFSR, Maharashtra, Sichuan, Bihar and Punjab ). It is currently 10th.

Culture

The Li Bai Memorial, located at Zhongba Town of northern Jiangyou County in Sichuan Province, is a museum in memory of Li Bai, a Chinese poet in the Tang Dynasty (618-907), at the place where he grew up. It was prepared in 1962 on the occasion of 1,200th anniversary of his death, completed in 1981 and opened to the public in October 1982. The memorial is built in the style of the classic garden of the Tang Dynasty.

In 2003, Sichuan had "88 art performing troupes, 185 culture centers, 133 libraries and 52 museums". Companies based in Sichuan also produced 23 television series and one film.[38]

Languages

The most widely used variety of Chinese spoken in Sichuan is Sichuanese, which is the lingua franca in Sichuan, Chongqing and part of Tibet. Although Sichuanese is generally classified as a dialect of Mandarin, it is highly divergent in phonology, vocabulary, and even grammar from the standard language.[39] Minjiang dialect is especially difficult for speakers of other Mandarin dialects to understand.[40][41][42][43]

The prefectures of Garzê and Ngawa (Aba) in western Sichuan are populated by Tibetan and Qiang people. Tibetans speak the Kham and Amdo languages within the Tibetic family, as well as various Qiangic languages. Qiangic languages are also spoken by the Qiang and other related ethnicities. The Yi of Liangshan prefecture in southern Sichuan speak the Yi language, which is more closely related to Burmese; Yi is written using the Yi script, a syllabary standardized in 1974. The Southwest University for Nationalities has one of China's most prominent Tibetology departments, and the Southwest Minorities Publishing House prints literature in minority languages.[44] In the minority inhabited regions of Sichuan, there is bi-lingual signage and public school instruction in non-Mandarin minority languages.

Cuisine

The Sichuanese are proud of their cuisine, known as one of the Four Great Traditions of Chinese cuisine. The cuisine here is of "one dish, one shape, hundreds of dishes, hundreds of tastes", as the saying goes, to describe its acclaimed diversity. The most prominent traits of Sichuanese cuisine are described by four words: spicy, hot, fresh and fragrant.[45] Sichuan cuisine is popular in the whole nation of China, so are Sichuan chefs. Two well-known Sichuan chefs are Chen Kenmin and his son Chen Kenichi, who was Iron Chef Chinese on the Japanese television series "Iron Chef".

-

Kung Pao chicken, one of the best known dishes of Sichuan cuisine

-

Hot pot in Mala style

-

Mixed sauce noodles (杂酱面)

Education

Colleges and universities

- Chengdu University of Technology

- Sichuan Normal University (Chengdu)

- Sichuan University (Chengdu)

- Southwest Jiaotong University (Chengdu)

- Southwest University for Nationalities (Chengdu)

- Southwestern University of Finance and Economics (Chengdu)

- University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (Chengdu)

- Southwest Petroleum University (Chengdu)

Tourism

- Dazu Rock Carvings, listed as property of the Chongqing municipality

- Huanglong Scenic and Historic Interest Area

- Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic and Historic Interest Area

- Mount Emei Scenic Area, including Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area

- Mount Qincheng and the Dujiangyan Irrigation System

- Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries

As of July 2013, the world's largest building the New Century Global Center is located in the city of Chendgu. At 328 feet (100 m) high, 1,640 feet (500 m) long, and 1,312 feet (400 m) wide, the Center houses retail outlets, a 14-theater cinema, offices, hotels, the Paradise Island waterpark, an artificial beach, a 164 yards (150 m)-long LED screen, skating rink, pirate ship, fake Mediterranean village, 24-hour artificial sun, and 15,000-spot parking area.[46]

Notable individuals

- Li Bai (701–762), one of the greatest poets of the Tang Dynasty

- Kuei-feng Tsung-mi (圭峰宗密; 780–841), a Tang dynasty Buddhist scholar-monk, fifth patriarch of the Huayan (華嚴) school as well as a patriarch of the Heze lineage of Southern Chan

- Ouyang Xiu (1007–September 22, 1072), Confucian historian, essayist, calligrapher, poet, and official bureaucrat of the Song Dynasty

- Su Xun (蘇洵), a poem and prose-writer of the Song Dynasty

- Su Shi (January 8, 1037 – August 24, 1101),Confucian bureaucrat official, a poet, artist, calligrapher, pharmacologist, gastronome, and official bureaucrat of the Song Dynasty

- Su Zhe (1039–1112), a poet and essayist, Confucian bureaucratic official of the Song Dynasty

- Ba Jin (November 25, 1904 – October 17, 2005), a Chinese novelist and writer

- Deng Xiaoping, Chinese Paramount Leader during the 1980s, his former residence is now a museum.

- Chen Kenmin, (June 27, 1912 - May 12, 1990), chef who specialized in Szechwan cuisine. Father of well-known Iron Chef Chen Kenichi.

Sports

Professional sports teams in Sichuan include:

- Chinese Basketball Association

- None

- Chinese Football Association Super League

- Chengdu Blades

- Chinese Volleyball League

- Sichuan Volleyball Team

- China Table Tennis Super League

- Sichuan Quan-Xing Table-Tennis Team

Sister states and regions

Washington, United States (1982)

Washington, United States (1982) Michigan, United States (1982)

Michigan, United States (1982) Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan (1984)

Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan (1984) Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan (1985)

Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan (1985) South P'yŏngan, North Korea (1985)

South P'yŏngan, North Korea (1985) Midi-Pyrénées, France (1987)

Midi-Pyrénées, France (1987) North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (1988)

North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (1988) Leicestershire, United Kingdom (1988)

Leicestershire, United Kingdom (1988) Piedmont, Italy (1990)

Piedmont, Italy (1990) Pernambuco, Brazil (1992)

Pernambuco, Brazil (1992) Tolna County, Hungary (1993)

Tolna County, Hungary (1993) Valencian Community, Spain (1994)

Valencian Community, Spain (1994).svg.png) Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium (1995)

Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium (1995) Barinas State, Venezuela (2001)

Barinas State, Venezuela (2001) Friesland, Netherlands (2001)

Friesland, Netherlands (2001) Almaty Province, Kazakhstan (2001)

Almaty Province, Kazakhstan (2001) Mpumalanga, South Africa (2002)

Mpumalanga, South Africa (2002) Suphan Buri, Thailand (2010)

Suphan Buri, Thailand (2010)

See also

- 2013 Ya'an, Sichuan earthquake

- Major national historical and cultural sites in Sichuan

- Eight Immortals from Sichuan

- Qutang Gorge

- The Good Person of Sezuan

References

- ↑ "Doing Business in China - Survey". Ministry Of Commerce - People's Republic Of China. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census [1] (No. 2)". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ↑ 《2013中国人类发展报告》 (PDF) (in Chinese). United Nations Development Programme China. 2013. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ↑ (Chinese) Origin of the Names of China's Provinces, People's Daily Online.

- ↑ Steven F. Sage (2006). Ancient Sichuan and the Unification of China. State University of New York Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-7914-1038-2.

- ↑ Shujing Original text: 王曰:「嗟!我友邦塚君御事,司徒、司鄧、司空,亞旅、師氏,千夫長、百夫長,及庸,蜀、羌、髳、微、盧、彭、濮人。稱爾戈,比爾干,立爾矛,予其誓。」

- ↑ Sanxingdui Museum; Wu Weixi; Zhu Yarong (2006). The Sanxingdui site: mystical mask on ancient Shu Kingdom. 五洲传播出版社. pp. 7–8. ISBN 7-5085-0852-1.

- ↑ Chang Qu. "Book 3 (卷三)". Chronicles of Huayang (華陽國志). pp. 90–91.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Terry F. Kleeman (1998). Ta Chʻeng, Great Perfection - Religion and Ethnicity in a Chinese Millennial Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 17–19, 22. ISBN 0-8248-1800-8.

- ↑ Sanxingdui Museum; Wu Weixi; Zhu Yarong (2006). The Sanxingdui site: mystical mask on ancient Shu Kingdom. 五洲传播出版社. pp. 5–6. ISBN 7-5085-0852-1.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Haw, Stephen G (2008). A Traveller's History of China. Interlink Books. p. 83.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Boland-Crewe, Tara; Lea, David (2004). The Territories of the People's Republic of China. Psychology Press. pp. 187–189.

- ↑ Roberts, John A.G. (2011). A History of China. Palgrave Essential Histories series. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 109. ISBN 9-7802-3034-5362.

- ↑ Guxi, Pan (2002). Chinese Architecture -- The Yuan and Ming Dynasties (English ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 245−246. ISBN 0-300-09559-7.

- ↑ "Skeletons of massacre victims uncovered at construction site". Shanghai Star. 11 April 2002.

- ↑ James B. Parsons (1957). "The Culmination of a Chinese Peasant Rebellion: Chang Hsien-chung in Szechwan, 1644-46". The Journal of Asian Studies 16 (3): 387–400. doi:10.2307/2941233.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Dai, Yingcong (2009). The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet: Imperial Strategy in the Early Qing. University of Washington Press. pp. 19–26, 145.

- ↑ Schuster, R.L. and G. F. Wieczorek, "Landslide triggers and types" in Landslides: Proceedings of the First European Conference on Landslides 2002 A.A. Balkema Publishers. p.66

- ↑ Cong, Xiaoping (2011). Teachers' Schools and the Making of the Modern Chinese Nation-State, 1897-1937. UBC Press. p. 203.

- ↑ Marks, Thomas A., Counterrevolution in China: Wang Sheng and the Kuomintang, Frank Cass (London: 1998), ISBN 0-7146-4700-4. Partial view on Google Books. p. 116.

- ↑ Cao Shuji: 大饑荒:1959-1961年的中国人口, Hong Kong: 2005

- ↑ Citypopulation.de:China

- ↑ National Statistics Agency Tables:4-3 Total Population and Birth Rate, Death Rate and Natural Growth Rate by Region (1997)

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Sichuan Province: Economic News and Statistics for Sichuan's Economy". Thechinaperspective.com. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ↑ "Casualties of the Wenchuan Earthquake" (in Chinese). Sina.com. 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2008-07-06., and "Wenchuan Earthquake has already caused 69,196 fatalities and 18,379 missing" (in Chinese). Sina.com. 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ↑ Lan Hong-xing (2012). "Study on Rural Poverty in Ecologically Fragile Areas-A Case Study of the Tibetan Areas in Sichuan Province" (PDF). Asian Agricultural Research (USA-China Science and Culture Media Corporation) 4 (1): 27–31, 61. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ↑ SICHUAN PROVINCE (hktdc.com)

- ↑ International Market Research - AUTO PARTS INDUSTRY IN SICHUAN AND CHONGQING

- ↑ CCTV

- ↑ Xinhua - English

- ↑ Counting the economic costs of China's earthquake_English_Xinhua

- ↑ "Chengdu Economic & Technological Development Zone". RightSite.asia. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ "Chengdu Export Processing Zone". RightSite.asia. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ "Chengdu Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone". RightSite.asia. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ RightSite.asia | Mianyang Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

- ↑ "Tibetans leave home to seek new opportunities". Xinhua. 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ↑ Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 123.

- ↑ Catherine, ed. (2004-05-26). "Sichuan: Education and Culture". newsgd.com. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ↑ 崔荣昌 (1996). "第三章:四川的官话". 《四川方言与巴蜀文化》. 四川大学出版社. ISBN 7-5614-1296-7.

- ↑ 李彬、涂鸣华 (2007). 《百年中国新闻人(上册)》. 福建人民出版社. p. 563. ISBN 978-7-211-05482-4.

- ↑ 吴丹, 梁晓明 (November 23, 2005). "四川交通:"窗口"飞来普通话". 中国交通报.

- ↑ 张国盛, 余勇 (June 1, 2009). "大学生村官恶补四川方言 现在能用流利四川话和村民交流". 北京晨报.

- ↑ "走进大山的志愿者". 四川青年报. July 18, 2009.

- ↑ "The Wuhou District (武侯区), a Tibetan enclave in Chengdu". TibetInfoNet. 2009-03-24. ISSN 1864-1407. Retrieved 2013-01-04.

- ↑ Sichuanese Cuisine (Chinese) - Pictures, descriptions, history, and examples of Sichuan cuisine.

- ↑ Roberto A. Ferdman (3 July 2013). "The world’s new largest building is four times the size of Vatican City". Quartz. Quartz. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sichuan. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sichuan. |

|

Qinghai | Gansu | Shaanxi |  |

| Tibet | |

Chongqing | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Yunnan | Guizhou |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||