Shoal

A shoal, sandbank, sandbar (or just bar in context), or gravelbar, is a characteristically linear landform completely within or extending into a body of water. It is typically composed of sand, silt, and/or small pebbles.

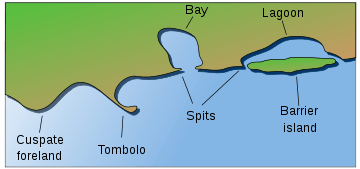

A spit—sandspit is a type of shoal.

Description

Shoals are characteristically long and narrow (linear) and develop where a stream, river, or ocean current promotes deposition of sediment and granular material, resulting in localized shallowing (shoaling) of the water.

Shoals can appear as a coastal landform in the sea, where they are classified as a type of ocean bank, or as fluvial landforms in rivers, streams, and lakes.

A shoal—sandbar may seasonally separate a smaller body of water from the sea, such as:

- marine lagoons

- brackish water estuaries

- freshwater seasonal stream and river mouths and deltas.

The term bar can apply to landform features spanning a considerable range in size, from a length of a few metres in a small stream to marine depositions stretching for hundreds of kilometers along a coastline, often called barrier islands.

Composition

They are typically composed of sand, although they could be of any granular matter that the moving water has access to and is capable of shifting around (for example, soil, silt, gravel, cobble, shingle, or even boulders). The grain size of the material comprising a bar is related to the size of the waves or the strength of the currents moving the material, but the availability of material to be worked by waves and currents is also important.

Formation

Wave shoaling is the process when surface waves move towards shallow water, such as a beach, they slow down, their wave height increases and the distance between waves decreases. This behavior is called shoaling, and the waves are said to shoal. The waves may or may not build to the point where they break, depending on how large they were to begin with, and how steep the slope of the beach is. In particular, waves shoal as they pass over submerged sandbanks or reefs. This can be treacherous for boats and ships.

Shoaling can also diffract waves, so the waves change direction. For example, if waves pass over a sloping bank which is shallower at one end than the other, then the shoaling effect will result in the waves slowing more at the shallow end. Thus the wave fronts will refract, changing direction like light passing through a prism. Refraction also occurs as waves move towards a beach if the waves come in at an angle to the beach, or if the beach slopes more gradually at one end than the other.

Types

Sandbars and longshore bars

Sandbars, also known as a trough bars, form where the waves are breaking, because the breaking waves set up a shoreward current with a compensating counter—current along the bottom. Sometimes this occurs seaward of a trough (marine landform).

Sand carried by the offshore moving bottom current is deposited where the current reaches the wave break.[1] Other longshore bars may lie further offshore, representing the break point of even larger waves, or the break point at low tide.

Harbour and river bars

A harbor or river bar is a sedimentary deposit formed at a harbor entrance or river mouth by: the deposition of freshwater sediment, or the action of waves on the sea floor or up—current beaches.

Where beaches are suitably mobile, or the river’s suspended and/or bed loads are large enough, deposition can build up a sandbar that completely blocks a river mouth and damming the river. It can be a seasonally natural process of aquatic ecology, causing the formation of estuaries and wetlands in the lower course of the river. This situation will persist until the bar is eroded by the sea, or the dammed river develops sufficient head to break through the bar.

The formation of harbor bars can prevent access for boats and shipping, can be the result of:

- construction up-coast or at the harbor — e.g.: breakwaters, dune habitat destruction.

- upriver development — e.g.: dams and reservoirs, riparian zone destruction, river bank alterations, river adjacent agricultural land practices, water diversions.

- watershed erosion from habitat alterations — e.g.: deforestation, wildfires, grading for development.

- artificially created/deepened harbors that require periodic dredging maintenance.

Nautical navigation

In a nautical sense, a bar is a shoal, similar to a reef: a shallow formation of (usually) sand that is a navigation or grounding hazard, with a depth of water of 6 fathoms (11 metres) or less. It therefore applies to a silt accumulation that shallows the entrance to or course of a river, or creek. A bar can form a dangerous obstacle to shipping, preventing access to the river or harbour in unfavourable weather conditions or at some states of the tide.

Shoals as geological units

In addition to longshore bars discussed above that are relatively small features of a beach, the term shoal can be applied to larger geological units that form off a coastline as part of the process of coastal erosion. These include spits and baymouth bars that form across the front of embayments and rias. A tombolo is a bar that forms an isthmus between an island or offshore rock and a mainland shore.

In places of re-entrance along a coastline (such as inlets, coves, rias, and bays), sediments carried by a longshore current will fall out where the current dissipates, forming a spit. An area of water isolated behind a large bar is called a lagoon. Over time, lagoons may silt up, becoming salt marshes.

In some cases, shoals may be precursors to beach expansion and dunes formation, providing a source of windblown sediment to augment such beach or dunes landforms.[2]

Barrier islands

Barrier islands are the largest type of the shoal geological units. Their geological sections include:

- Lower shoreface

The shoreface is the part of the barrier where the ocean meets the shore of the island. The barrier island body itself separates the shoreface from the backshore and lagoon/tidal flat area. Characteristics common to the lower shoreface are fine sands with mud and possibly silt. Further out into the ocean the sediment becomes finer. The effect from the waves at this point is weak because of the depth. Bioturbation is common and many fossils can be found here.

- Middle shoreface

The middle shore face is located in the upper shoreface. The middle shoreface is strongly influenced by wave action because of its depth. Closer to shore the grain size will be medium size sands with shell pieces common. Since wave action is heavier, bioturbation is not likely.

- Upper shoreface

The upper shore face is constantly effected by wave action. This results in development of herringbone sedimentary structures because of the constant differing flow of waves. Grain size is larger sands.

- Foreshore

The foreshore is the area on land between high and low tide. Like the upper shoreface, it is constantly affected by wave action. Cross bedding and lamination are present and coarser sands are present because of the high energy present by the crashing of the waves. The sand is also very well sorted.

- Backshore

The backshore is always above the highest water level point. The berm is also found here which marks the boundary between the foreshore and backshore. Wind is the important factor here, not water. During strong storms high waves and wind can deliver and erode sediment from the backshore.

- Dunes

The dunes are located at the top of the backshore. The dunes are typical of a barrier island. The high sand dunes are only affected by wind because of their height. Similarly, strong storms are the only thing that really affect the size of the dunes. The dunes will display characteristics of typical eolian wind blown dunes. The difference here is that dunes on a barrier island typically contain vegetation roots and marine bioturbation.

- Lagoon and tidal flats

The lagoon and tidal flat area is located behind the dune and backshore area. Here the water is still and this allows for fine silts, sands, and mud to settle out. Lagoons can become host to an anaerobic environment. This will allow high amounts of organic rich mud to form. Vegetation is also common.

Human habitation

Since prehistoric times humans have chosen some shoals as a site of habitation. In some early cases the locations provided easy access to exploit marine resources.[3] In modern times these sites are sometimes chosen for the water amenity or view, but many such locations are prone to storm damage.[4][5]

See also

- Category:Shoals

- Ayre (landform)

- Riverbank

- Coastal Barrier Resources Act — 1982 U.S. law.

References

- ↑ W. Bascom, 1980. Waves and Beaches. Anchor Press/Doubleday, Garden City, New York. 366 p

- ↑ Mirko Ballarini, Optical Dating of Quartz from Young Deposits, IOS Press, 2006 146 pages, ISBN 1-58603-616-5

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan (2008) Morro Creek, ed. by Andy Burnham

- ↑ Dick Morris (2008) Fleeced

- ↑ Jefferson Beale Browne (1912) Key West: The Old and the New, published by The Record company