Sharkskin

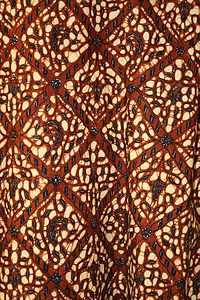

Sharkskin is a smooth worsted fabric with a soft texture and a two-toned woven appearance.

Sharkskin fabric's lightweight and wrinkle-free properties make it ideal for curtains, tablecloths and napkins. Sharkskin fabric is popular for both men’s and women’s worsted suits, light winter jackets and coats. Sharkskin is commonly used as a liner in diving suits and wetsuits.

Typically, sharkskin fabric is made with the use of rayon or acetate or as a blend of the two, and its two-toned woven appearance is achieved by basketweaving, thereby creating a pattern where the colored threads run diagonal to the white fibers. Because both fabric options already have a relatively smooth texture, the combination results in the finish for which sharkskin fabric is known.

Composition

The finest "natural sharkskin" fabric has been historically made of all natural fibers, being some mixture of mohair, wool and silk.

More expensive variations, often demarcated by fabric content labels bearing "Golden Fleece", "Royal" or the like, indicate an extremely rare and costly "sharkskin" of yester-year. Those fabrics, produced in small quantities, were manufactured in South America (Peru and Argentina: by transplanted German/Italian weavers) from the 1950s and 60s and are known to include in some instances even small percentages of vicuna, guanaco or alpaca in such blends: inclusion of silk (then a very costly fiber) was even more common among the "natural sharkskins". Whereas, "artificial sharkskin", a much less costly substitute, is a fabric variant that is more often found from that period and can contain synthesized or synthetic fibers that were developed contemporary to those eras.

Artificial variations

Artificial sharkskin variants used for suiting first appeared in the 1950s and rapidly garnered world-wide appeal in artificial sharkskin (costing much less than its "natural" counterpart: which most consumers were not aware existed, so far out of their price range it remained), attaining broad popularity in the early 1960s, followed by brief fashion resurgences in the mid-1980s, mid-1990s and enjoying occasional fashion popularity throughout the 2000s: its variations often contain some wool percentage blend. More recently, such artificial sharkskin fabrics have undergone technological improvements and have attained new desirability, even among "fabric purists" who would have conventionally rejected out-of-hand any "artificial sharkskin" substitutes for the real item containing a majority percentage of mohair.

The term "Super-Sharkskin" has been used to describe relatively costly sharkskin fabrics which include some percentage of synthetic fibers. The addition of synthetics and can create a heightened metallic-like sheen, and/or added flexibility (as with a 2% Lycra blend).

Fashionability

Many attribute the "fading in and out of fashion" of sharkskin of any sort to the fact that many of the ubiquitous "artificial sharkskin" variants had "created an indelible public impression that all sharkskin ought to be deemed "tacky", to be eschewed, as it is in Lisa Birnbach's Official Preppy Handbook, 1980, which reflected, and in itself, in-turn, influenced, many consumers' misgivings regarding its social status.

Importantly, whether "natural" or "artificial", today the line between the two has been blurred by the advance of innovative blends. Nonetheless, "natural sharkskin" from the 1950s and 1960s men's and women's suits remain highly sought in the vintage clothing market, commanding extraordinary prices online. The most desired sharkskin colors feature a peacock iridescent palette.

Sharkskin Dinner Suit in Middle East

British Diplomat Sir Terence Clark in the 50's served in Bahrain. He reminisces that the requisite winter evening wear for a diplomat was a white sharkskin dinner jacket.[1] Lucette Lagnado in her prize-winning memoir about her childhood, The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit: My Family's Exodus from Old Cairo to the New World uses the imagery of the white sharkskin suit to evoke the glamorous evening life in Egypt in the 50's.

See also

References

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge. British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP). Archived interview: Former member of the British Diplomatic service Charles Cullimore interviews fellow diplomat Sir Terence Clark on Friday 8, November 2002. Retrieved: June 8, 20111. http://www.chu.cam.ac.uk/archives/collections/BDOHP/Clark.pdf

.svg.png)