Shang dynasty

| Shang dynasty | |||||

| 商朝 | |||||

| Kingdom | |||||

| |||||

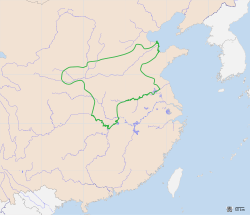

Remnants of advanced, stratified societies dating back to the Shang period have been found in the Yellow River Valley. | |||||

| Capital | Anyang | ||||

| Languages | Old Chinese | ||||

| Religion | Chinese folk religion | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||

| - | Established | c. 1600 BC | |||

| - | Battle of Muye | c. 1046 BC | |||

| Area | |||||

| - | 1122 BC est.[1] | 1,250,000 km² (482,628 sq mi) | |||

| Shang dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 商朝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | Shang dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 殷代 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Yin era | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Shang dynasty (Chinese: 商朝; pinyin: Shāng cháo) or Yin dynasty (Chinese: 殷代; pinyin: Yīn dài), according to traditional historiography, ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, succeeding the Xia dynasty and followed by the Zhou dynasty. The classic account of the Shang comes from texts such as the Book of Documents, Bamboo Annals and Records of the Grand Historian. According to the traditional chronology based upon calculations made approximately 2,000 years ago by Liu Xin, the Shang ruled from 1766 to 1122 BC, but according to the chronology based upon the "current text" of Bamboo Annals, they ruled from 1556 to 1046 BC. The Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project dated them from c. 1600 to 1046 BC.

Archaeological work at the Ruins of Yin (near modern-day Anyang), which has been identified as the last Shang capital, uncovered eleven major Yin royal tombs and the foundations of palaces and ritual sites, containing weapons of war and remains from both animal and human sacrifices. Tens of thousands of bronze, jade, stone, bone, and ceramic artifacts have been obtained.

The Anyang site has yielded the earliest known body of Chinese writing, mostly divinations inscribed on oracle bones – turtle shells, ox scapulae, or other bones. More than 20,000 were discovered in the initial scientific excavations during the 1920s and 1930s, and over four times as many have been found since. The inscriptions provide critical insight into many topics from the politics, economy, and religious practices to the art and medicine of this early stage of Chinese civilization.[2]

Traditional accounts

Many events concerning the Shang dynasty are mentioned in various Chinese classics, including the Book of Documents, the Mencius and the Zuo Zhuan. Working from all the available documents, the Han dynasty historian Sima Qian assembled a sequential account of the Shang dynasty as part of his Records of the Grand Historian. His history describes some events in detail, while in other cases only the name of a king is given.[3] A closely related, but slightly different, account is given by the Bamboo Annals. The Annals were interred in 296 BC, but the text has a complex history and the authenticity of the surviving versions is controversial.[4]

The name Yīn (殷) is used by Sima Qian for the dynasty, and in the Bamboo Annals for both the dynasty and its final capital. It has been a popular name for the Shang throughout history, and is often used specifically to describe the later half of the Shang dynasty. In Japan and Korea, the Shang are still referred to almost exclusively as the Yin (In) dynasty. However it seems to have been the Zhou name for the earlier dynasty.

The word does not appear in the oracle bones, which refer to the state as Shāng (商), and the capital as Dàyì Shāng (大邑商 "Great Settlement Shang").[5]

Course of the dynasty

Sima Qian's Annals of the Yin begins by describing the predynastic founder of the Shang lineage, Xie (偰) — also appearing as Qi (契) — as having been miraculously conceived when Jiandi, a wife of Emperor Ku, swallowed an egg dropped by a black bird. Xie is said to have helped Yu the Great to control the Great Flood and for his service to have been granted a place called Shang as a fief.[6]

Sima Qian relates that the dynasty itself was founded 13 generations later, when Xie's descendant Tang overthrew the impious and cruel final Xia ruler in the Battle of Mingtiao. The Records recount events from the reigns of Tang, Tai Jia, Tai Wu, Pan Geng, Wu Ding, Wu Yi and the depraved final king Di Xin, but the rest of the Shang rulers are merely mentioned by name. According to the Records, the Shang moved their capital five times, with the final move to Yin in the reign of Pan Geng inaugurating the golden age of the dynasty.[7]

Di Xin, the last Shang king, is said to have committed suicide after his army was defeated by Wu of Zhou. Legends say that his army and his equipped slaves betrayed him by joining the Zhou rebels in the decisive Battle of Muye. According to the Yi Zhou Shu and Mencius the battle was very bloody. The classic, Ming-era novel Fengshen Yanyi retells the story of the war between Shang and Zhou as a conflict where rival factions of gods supported different sides in the war.

After the Shang were defeated, King Wu allowed Di Xin's son Wu Geng to rule the Shang as a vassal kingdom. However, Zhou Wu sent three of his brothers and an army to ensure that Wu Geng would not rebel.[8][9][10] After Zhou Wu's death, the Shang joined the Rebellion of the Three Guards against the Duke of Zhou, but the rebellion collapsed after three years, leaving Zhou in control of Shang territory.

Descendants

After Shang's collapse, Zhou's rulers forcibly relocated "Yin diehards" (殷頑) and scattered them throughout Zhou territory.[11] Some surviving members of the Shang royal family collectively changed their surname from the ancestral name Zi (子) to the name of their fallen dynasty, Yin. The family retained an aristocratic standing and often provided needed administrative services to the succeeding Zhou dynasty. The Records of the Grand Historian states that King Cheng of Zhou, with the support of his regent and uncle, the Duke of Zhou, enfeoffed Weiziqi (微子啟), a brother of Di Xin, as the Duke of Song, with its capital at Shangqiu. The Dukes of Song would maintain rites honoring the Shang kings until Song was conquered by Qi in 286 BC. Confucius was a descendant of the Shang Kings through the Dukes of Song.[12][13][14] The Dukes of Yansheng are in turn the descendants of Confucius.

The vassal state of Guzhu, located in what is now Tangshan, was formed by another remnant of the Shang, and was destroyed by Duke Huan of Qi.[15][16][17] Many Shang clans that migrated northeast after the dynasty's collapse were integrated into Yan culture during the Western Zhou period. These clans maintained an elite status and continued practicing the sacrificial and burial traditions of the Shang.[18]

Both Korean and Chinese legends, including reports in the Book of Documents and the Bamboo Annals, state that a disgruntled Shang prince named Jizi, who had refused to cede power to the Zhou, left China with a small army. According to these legends, he founded a state known as Gija Joseon in northwest Korea during the Gojoseon period of ancient Korean history. However, the historical accuracy of these legends is widely debated by scholars.

Early Bronze Age archaeology

Before the 20th century, the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC) was the earliest Chinese dynasty that could be verified from its own records. However during the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), antiquarians collected bronze ritual vessels attributed to the Shang era, some of which bore inscriptions.[19]

Yellow River valley

In 1899, it was found that Chinese pharmacists were selling "dragon bones" marked with curious and archaic characters.[19] These were finally traced back in 1928 to a site (now called Yinxu) near Anyang, north of the Yellow River in modern Henan province, where the Academia Sinica undertook archeological excavation until the Japanese invasion in 1937.[19]

Archaeologists focused on the Yellow River valley in Henan as the most likely site of the states described in the traditional histories. After 1950, remnants of an earlier walled city were discovered near Zhengzhou.[19] It has been determined that the earth walls at Zhengzhou, erected in the 15th century BC, would have been 20 m (66 ft) wide at the base, rising to a height of 8 m (26 ft), and formed a roughly rectangular wall 7 km (4 mi) around the ancient city.[20][21] The rammed earth construction of these walls was an inherited tradition, since much older fortifications of this type have been found at Chinese Neolithic sites of the Longshan culture (c. 3000–2000 BC).[20]

In 1959, the site of the Erlitou culture was found in Yanshi, south of the Yellow River near Luoyang.[20] Radiocarbon dating suggests that the Erlitou culture flourished ca. 2100 BC to 1800 BC. They built large palaces, suggesting the existence of an organized state.[22]

The remains of a walled city of about 470 hectares (1,200 acres) were discovered in 1999 across the Huan River from the Yinxu site. The city, now known as Huanbei, was apparently occupied for less than a century and destroyed shortly before the construction of the Yinxu complex.[23][24]

Chinese historians living in later periods were accustomed to the notion of one dynasty succeeding another, and readily identified the Zhengzhou and Erlitou sites with the early Shang and Xia dynasty of traditional histories. The actual political situation in early China may have been more complicated, with the Xia and Shang being political entities that existed concurrently, just as the early Zhou, who established the successor state of the Shang, are known to have existed at the same time as the Shang.[18]

Other sites

The Erligang culture represented by the Zhengzhou site is found across a wide area of China, even as far northeast as the area of modern Beijing, where at least one burial in this region during this period contained both Erligang-style bronzes and local-style gold jewelry.[18] The discovery of a Chenggu-style ge dagger-axe at Xiaohenan demonstrates that even at this early stage of Chinese history, there were some ties between the distant areas of north China.[18] The Panlongcheng site in the middle Yangtze valley was an important regional center of the Erligang culture.[25]

Accidental finds elsewhere in China have revealed advanced civilizations contemporaneous with but culturally unlike the settlement at Anyang, such as the walled city of Sanxingdui in Sichuan. Western scholars are hesitant to designate such settlements as belonging to the Shang dynasty.[26] Also unlike the Shang, there is no known evidence that the Sanxingdui culture had a system of writing. The late Shang state at Anyang is thus generally considered the first verifiable civilization in Chinese history.[5] In contrast, the earliest layers of the Wucheng site, pre-dating Anyang, have yielded pottery fragments containing short sequences of symbols, suggesting that they may be a form of writing quite different in form from oracle bone characters, but the sample is too small for decipherment.[27][28][29]

Genetic studies

A study of mitochondrial DNA (inherited in the maternal line) from Yinxu graves showed similarity with modern northern Han Chinese, but significant differences from southern Han Chinese.[30]

Late Shang at Anyang

The oldest extant direct records date from around 1200 BC at Anyang, covering the reigns of the last nine Shang kings. The Shang had a fully developed system of writing, preserved on bronze inscriptions and a small number of other writings on pottery, jade and other stones, horn, etc., but most prolifically on oracle bones.[31] The complexity and sophistication of this writing system indicates an earlier period of development, but direct evidence of that development is still lacking. Other advances included the invention of many musical instruments and observations of Mars and various comets by Shang astronomers.[32]

Their civilization was based on agriculture and augmented by hunting and animal husbandry.[33] In addition to war, the Shang also practiced human sacrifice.[34] Cowry shells were also excavated at Anyang, suggesting trade with coast-dwellers, but there was very limited sea trade in ancient China since China was isolated from other large civilizations during the Shang period.[35] Trade relations and diplomatic ties with other formidable powers via the Silk Road and Chinese voyages to the Indian Ocean did not exist until the reign of Emperor Wu during the Han dynasty (206 BC–221 AD).[36][37]

Court life

At the excavated royal palace of Yinxu, large stone pillar bases were found along with rammed earth foundations and platforms, which according to Fairbank, were "as hard as cement."[19] These foundations in turn originally supported 53 buildings of wooden post-and-beam construction.[19] In close proximity to the main palatial complex, there were underground pits used for storage, servants' quarters, and housing quarters.[19]

Many Shang royal tombs had been tunneled into and ravaged by grave robbers in ancient times,[38] but in the spring of 1976, the discovery of Tomb 5 at Yinxu revealed a tomb that was not only undisturbed, but one of the most richly furnished Shang tombs that archaeologists had yet come across.[39] With over 200 bronze ritual vessels and 109 inscriptions of Lady Fu Hao's name, archaeologists realized they had stumbled across the tomb of the militant consort to King Wu Ding, as described in 170 to 180 Shang oracle bones.[40] Along with bronze vessels, stoneware and pottery vessels, bronze weapons, jade figures and hair combs, and bone hairpins were found.[41][42][43] Historian Robert L. Thorp states that the large assortment of weapons and ritual vessels in her tomb correlate with the oracle bone accounts of her military career and involvement in Wu Ding's ritual ancestral sacrifices.[44]

The capital was the center of court life. Over time, court rituals to appease spirits developed, and in addition to his secular duties, the king would serve as the head of the ancestor worship cult. Often, the king would even perform oracle bone divinations himself, especially near the end of the dynasty. Evidence from excavations of the royal tombs indicates that royalty were buried with articles of value, presumably for use in the afterlife. Perhaps for the same reason, hundreds of commoners, who may have been slaves, were buried alive with the royal corpse.

A line of hereditary Shang kings ruled over much of northern China, and Shang troops fought frequent wars with neighboring settlements and nomadic herdsmen from the inner Asian steppes. The Shang king, in his oracular divinations, repeatedly shows concern about the fang groups, the barbarians living outside of the civilized tu regions, which made up the center of Shang territory. In particular, the tufang group of the Yanshan region were regularly mentioned as hostile to the Shang.[18]

Apart from their role as the head military commanders, Shang kings also asserted their social supremacy by acting as the high priests of society and leading the divination ceremonies.[45] As the oracle bone texts reveal, the Shang kings were viewed as the best qualified members of society to offer sacrifices to their royal ancestors and to the high god Di, who in their beliefs was responsible for the rain, wind, and thunder.[45]

Religion

Shang religion consisted of a mixture of shamanism, divination and sacrifice. There were six main recipients of sacrifice: (1) Di, the High God, (2) nature powers like the sun and mountain powers, (3) former lords, deceased humans who had been added to the dynastic pantheon, (4) predynastic ancestors, (5) dynastic ancestors, and (6) dynastic ancestresses such as the concubines of a past emperor.[46] The Shang rulers subscribed to the notion that these ancestors held power over them and performed rituals to ascertain their intentions.[46]

One of the most common rituals was divination, which often was performed to determine whether ancestors desired specific sacrifices or rituals. Divination involved cracking a turtle carapace or ox scapula to answer a question, and to then record the response to that question on the bone itself.[47] It is unknown what criteria the diviners used to determine the response, but it is believed to be the sound or pattern of the cracks on the bone.

The Shang also seem to have believed in an afterlife, as evidenced by the elaborate burial tombs built for deceased rulers. Often "carriages, utensils, sacrificial vessels, [and] weapons" would be included in the tomb.[48] A king's burial involved the burial of up to several hundred humans and horses as well to accompany the king into the afterlife, in some cases even numbering four hundred.[48] Finally, tombs included ornaments such as jade, which the Shang may have believed to protect against decay or confer immortality.

The degree to which shamanism was a central aspect of Shang religion is a subject of debate.[47][49]

The Shang religion was highly bureaucratic and meticulously ordered. Oracle bones contained descriptions of the date, ritual, person, ancestor, and questions associated with the divination.[47] Tombs displayed highly ordered arrangements of bones, with groups of skeletons laid out facing the same direction.

Bronze working

Chinese bronze casting and pottery advanced during the Shang dynasty, with bronze typically being used for ritually significant, rather than primarily utilitarian, items. As far back as c. 1500 BC, the early Shang dynasty engaged in large-scale production of bronze-ware vessels and weapons.[50] This production required a large labor force that could handle the mining, refining, and transportation of the necessary copper, tin, and lead ores. This in turn created a need for official managers that could oversee both hard-laborers and skilled artisans and craftsmen.[50] The Shang royal court and aristocrats required a vast amount of different bronze vessels for various ceremonial purposes and events of religious divination.[50] Ceremonial rules even decreed how many bronze containers of each type a nobleman or noblewoman of a certain rank could own. With the increased amount of bronze available, the army could also better equip itself with an assortment of bronze weaponry. Bronze was also used for the fittings of spoke-wheeled chariots, which appeared in China around 1200 BC.[45]

Military

Bronze weapons were an integral part of Shang society.[51] Shang infantry were armed with a variety of stone and bronze weaponry, including máo spears, yuè pole-axes, gē pole-based dagger-axes, composite bows, and bronze or leather helmets.[52][53] The chariot first appeared in China during the reign of Wu Ding. Oracle bone inscriptions suggest that the western enemies of the Shang used limited numbers of chariots in battle, but the Shang themselves used them only as mobile command vehicles and in royal hunts. It is little doubt that the chariot entered China through the Central Asia and the Northern Steppe, possibly indicating some form of contact with the Indo-Europeans.[54] Recent archaeological finds have shown that the late Shang used horses, chariots, bows and practiced horse burials that are similar to the steppe peoples to the west.[55][56] Other possible cultural influences resulting from Indo-European contact may include fighting styles, head-and-hoof rituals, art motifs and myths.[56] These influences have led one scholar, Christopher I. Beckwith, to speculate that Indo-Europeans "may even have been responsible for the foundation of the Shang Dynasty," though he admits there is no direct evidence.[57] A crucial factor in the Zhou conquest of the Shang may have been their more effective use of chariots.[58]

Although the Shang depended upon the military skills of their nobility, Shang rulers could mobilize the masses of town-dwelling and rural commoners as conscript laborers and soldiers for both campaigns of defense and conquest.[59] Aristocrats and other state rulers were obligated to furnish their local garrisons with all necessary equipment, armor, and armaments. The Shang king maintained a force of about a thousand troops at his capital and would personally lead this force into battle.[60] A rudimentary military bureaucracy was also needed in order to muster forces ranging from three to five thousand troops for border campaigns to thirteen thousand troops for suppressing rebellions against Shang dynasty.

Kings

The earliest records are the oracle bones inscribed during the reigns of the Shang kings from Wu Ding.[61] The oracle bones do not contain king lists, but they do record the sacrifices to previous kings and the ancestors of the current king, which follow a standard schedule that scholars have reconstructed. From this evidence, scholars have assembled the implied king list and genealogy, finding that it is in substantial agreement with the later accounts, especially for later kings.[62]

The Shang kings were referred to in the oracle bones by posthumous names. The last character of each name is one of the 10 celestial stems, which also denoted the day of the 10-day Shang week on which sacrifices would be offered to that ancestor within the ritual schedule. There were more kings than stems, so the names have distinguishing prefixes such as 大 Dà (greater), 中 Zhōng (middle), 小 Xiǎo (lesser), 卜 Bǔ (outer), 祖 Zǔ (ancestor) and a few more obscure names.[63]

The kings, in the order of succession derived from the oracle bones, are here grouped by generation. Later reigns were assigned to oracle bone diviner groups by Dong Zuobin:[64]

| Generation | Older brothers | Main line of descent | Younger brothers | Diviner group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 大乙 Dà Yǐ[lower-alpha 1] | [lower-alpha 2] | ||||

| 2 | 大丁 Dà Dīng[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

| 3 | 大甲 Dà Jiǎ | 卜丙 Bǔ Bǐng[lower-alpha 4] | ||||

| 4 | [lower-alpha 5] | 大庚 Dà Gēng | 小甲 Xiǎo Jiǎ[lower-alpha 6] | |||

| 5 | 大戊 Dà Wù | 呂己 Lǚ Jǐ[lower-alpha 7] | ||||

| 6 | 中丁 Zhōng Dīng[lower-alpha 8] | 卜壬 Bǔ Rén | ||||

| 7 | 戔甲 Jiān Jiǎ | 祖乙 Zǔ Yǐ | ||||

| 8 | 祖辛 Zǔ Xīn | 羌甲 Qiāng Jiǎ[lower-alpha 9] | ||||

| 9 | 祖丁 Zǔ Dīng | 南庚 Nán Gēng[lower-alpha 10] | ||||

| 10 | 象甲 Xiàng Jiǎ | 盤庚 Pán Gēng | 小辛 Xiǎo Xīn | 小乙 Xiǎo Yǐ | ||

| 11 | 武丁 Wǔ Dīng | I | ||||

| 12 | [lower-alpha 11] | 祖庚 Zǔ Gēng | 祖甲 Zǔ Jiǎ | II | ||

| 13 | 廩辛 Lǐn Xīn[lower-alpha 12] | 康丁 Kāng Dīng | III | |||

| 14 | 武乙 Wǔ Yǐ | IV | ||||

| 15 | 文武丁 Wén Wǔ Dīng | |||||

| 16 | 帝乙 Dì Yǐ[lower-alpha 13] | V | ||||

| 17 | 帝辛 Dì Xīn[lower-alpha 14] | |||||

- Notes

- ↑ The first king is known as Tang in the Historical Records. The oracle bones also identify six pre-dynastic ancestors: 上甲 Shàng Jiǎ, 報乙 Bào Yǐ, 報丙 Bào Bǐng, 報丁 Bào Dīng, 示壬 Shì Rén and 示癸 Shì Guǐ.

- ↑ There is no firm evidence of oracle bone inscriptions before the reign of Wu Ding.

- ↑ According to the Historical Records and the Mencius, Da Ding (there called Tai Ding) died before he could ascend to the throne. However in the oracle bones he receives rituals like any other king.

- ↑ According to the Historical Records, Bu Bing (there called Wai Bing) and 仲壬 Zhong Ren (not mentioned in the oracle bones) were younger brothers of Dai Ting and preceded Da Jia (also known as Dai Jia). However the Mencius, the Commentary of Zuo and the Book of History state that he reigned after Da Jia, as also implied by the oracle bones.

- ↑ The Historical Records include a king Wo Ding not mentioned in the oracle bones.

- ↑ The Historical Records have Xiao Jia as the son of Da Geng (known as Tai Geng) in the "Annals of Yin", but as a younger brother (as implied by the oracle bones) in the "Genealogical Table of the Three Ages".

- ↑ According to the Historical Records, Lü Ji (there called Yong Ji) reigned before Da Wu (there called Tai Wu).

- ↑ The kings from Zhong Ding to Nan Geng are placed in the same order by the Historical Records and the oracle bones, but there are some differences in genealogy, as described in the articles on individual kings.

- ↑ The status of Qiang Jia varies over the history of the oracle bones. During the reigns of Wu Ding, Di Yi and Di Xin, he was not included in the main line of descent, a position also held by the Historical Records, but in the intervening reigns he was included as a direct ancestor.

- ↑ According to the Historical Records, Nan Geng was the son of Qiang Jia (there called Wo Jia).

- ↑ The oracle bones and the Historical Records include an older brother 祖己 Zǔ Jǐ who did not reign.

- ↑ Lin Xin is named as a king in the Historical Records and oracle bones of succeeding reigns, but not those of the last two kings.[65]

- ↑ There are no ancestral sacrifices to the last two kings on the oracles bones, due to the fall of Shang. Their names, including the character 帝 Dì "emperor", come from the much later Bamboo Annals and Historical Records.[66]

- ↑ also referred to as Zhòu (紂), Zhòu Xīn (紂辛) or Zhòu Wáng (紂王) or by adding "Shāng" (商) in front of any of these names.

Gallery

- Late Shang artifacts

-

Jade carved deer

-

Jade carved fish

-

Jade carved tiger

-

Bronze gefuding guǐ vessel

-

Bronze yuefu you vessel

-

Bronze pou vessel with four ram heads

-

Bronze zūn ritual vessel

-

Bronze guang ritual ewer

-

Bronze pot with lid and handle

-

A late Shang, ritual bronze wine vessel (zun) in the unusual shape of an owl with a domed head for its lid

-

Bronze yuè axe

-

Shang/Zhou sculpture, 14–10th century BC

-

White pottery with a carved geometric pattern

See also

References

- Citations

- ↑ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires" (PDF). Journal of world-systems research 12 (2): 219–29. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ Keightley (2000).

- ↑ Keightley (1999), pp. 233–235.

- ↑ Keightley (1978b).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Keightley (1999), p. 232.

- ↑ Keightley (1999), p. 233, with additional details from the Historical Records.

- ↑ Keightley (1999), p. 233.

- ↑ 邶、鄘二國考 (Bei, Yong two national test)

- ↑ 周初"三监"与邶、鄘、卫地望研究 (Bei, Yong, Wei – looking at the research)

- ↑ "三监"人物疆地及其地望辨析 ——兼论康叔的始封地问题 (breaking ground on Kangshu problem)

- ↑ 一 被剥削者的存在类型 (Expoited by the presence of...)

- ↑ Xinzhong Yao (2000). An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0521644305.

- ↑ Xinzhong Yao (1997). Confucianism and Christianity: A Comparative Study of Jen and Agape. Sussex Academic Press. p. 29. ISBN 1898723761.

- ↑ Lee Dian Rainey (2010). Confucius & Confucianism: The Essentials. John Wiley & Sons. p. 66. ISBN 1405188413.

- ↑ 中国孤竹文化网 (Chinese Guzhu Cultural Network)

- ↑ 解开神秘古国 ——孤竹之谜 (unlocking the ancient mystery of Guzhu)

- ↑ 孤竹析辨 (Guzhu analysis identified)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Sun (2006).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 33.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 34.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 43.

- ↑ Fairbank & Goldman (2006), pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Harrington, Spencer P.M. (May–June 2000). "Shang City Uncovered". Archaeology (Archaeological Institute of America) 53 (3).

- ↑ Tang, Jigen; Jing, Zhichun; Liu, Zhongfu; Yue, Zhanwei (2004). "Survey and Test Excavation of the Huanbei Shang City in Anyang" (PDF). Chinese Archaeology 4: 1–20.

- ↑ Bagley (1999), pp. 168–171.

- ↑ Bagley (1999), pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Wilkinson (2000), p. 382.

- ↑ Wagner (1993), p. 20.

- ↑ Cheung (1983).

- ↑ Zeng, Wen; Li, Jiawei; Yue, Hongbin; Zhou, Hui; Zhu, Hong (2013). Poster: Preliminary Research on Hereditary Features of Yinxu Population. 82nd Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists.

- ↑ Qiu (2000), p. 60.

- ↑ A Short History of China.

- ↑ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, Dahia Ibo Shabaka, (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ↑ Flad, Dr. Rowan (28 Feb 2010). "Shang Dynasty Human Sacrifice". NGC Presents (National Geographic). Retrieved 3 Mar 2010.

- ↑ Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 35.

- ↑ Sun (1989), pp. 161–167.

- ↑ Chen (2002), pp. 67–71.

- ↑ Thorp (1981), p. 239.

- ↑ Thorp (1981), p. 240.

- ↑ Thorp (1981), pp. 240, 245.

- ↑ Thorp (1981), pp. 242, 245.

- ↑ Li (1980), pp. 393–394.

- ↑ Lerner et al. (1985), p. 77.

- ↑ Thorp (1981), p. 245.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 14.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Keightley (2004).

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Chang (1994).

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Smith (1961).

- ↑ Keightley (1998).

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 17.

- ↑ Sawyer & Sawyer (1994).

- ↑ Wang (1993).

- ↑ Sawyer & Sawyer (1994), p. 35.

- ↑ "China: History: The Shang Dynasty: The Chariot". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "The Steppe: Horsepowered warfare". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Krech & Steinicke 2011, p. 100

- ↑ Beckwith 2009, pp. 43–48

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1988).

- ↑ Sawyer & Sawyer (1994), p. 33.

- ↑ Sawyer & Sawyer (1994), p. 34.

- ↑ Wilkinson (2000), p. 397.

- ↑ Keightley (1999), p. 235.

- ↑ Smith (2011), pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Keightley (1999), pp. 234–235, 240–241.

- ↑ Keightley (1978a), p. 187.

- ↑ Keightley (1978a), pp. 187, 207, 209.

- Works cited

- Bagley, Robert (1999), "Shang archaeology", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L., The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 124–231, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 14008-29941. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Chang, Kwang-Chih (1994), "Shang Shamans", in Peterson, Willard J., The Power of Culture: Studies in Chinese Cultural History, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, pp. 10–36, ISBN 978-962-201-596-8.

- Chen, Yan (2002), Maritime Silk Route and Chinese-Foreign Cultural Exchanges, Beijing: Peking University Press, ISBN 978-7-301-03029-5.

- Cheung, Kwong-yue (1983), "Recent archaeological evidence relating to the origin of Chinese characters", in Keightley, David N.; Barnard, Noel, The Origins of Chinese Civilization, trans. Noel Barnard, University of California Press, pp. 323–391, ISBN 978-0-520-04229-2.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-618-13384-0.

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006), China: A New History (2nd ed.), Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03665-9.

- Keightley, David N. (1978a), Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-02969-0; A 1985 paperback 2nd edition is still in print, ISBN 0-520-05455-5.

- —— (1978b), "The Bamboo Annals and Shang-Chou Chronology", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 38 (2): 423–438, JSTOR 2718906.

- —— (1998), "Shamanism, Death, and the Ancestors: Religious Mediation in Neolithic and Shang China (ca. 5000–1000 B.C.)", Asiatische Studien 52 (3): 763–831, doi:10.5169/seals-147432.

- —— (1999), "The Shang: China's first historical dynasty", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L., The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 232–291, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- —— (2000), The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200–1045 B.C.), China Research Monograph 53, Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley, ISBN 978-1-55729-070-0.

- —— (2004), "The Making of the Ancestors: Late Shang Religion and Its Legacy", in Lagerwey, John, Chinese Religion and Society: The Transformation of a Field, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, pp. 3–63, ISBN 978-962-99612-3-7.

- Krech, Volkhard; Steinicke, Marian (2011). Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe: Encounters, Notions, and Comparative Perspectives. Brill. ISBN 9004225358. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Lerner, Martin; Murck, Alfreda; Ford, Barbara B.; Hearn, Maxwell; Valenstein, Suzanne G. (1985), "Asian Art", Recent Acquisitions (Metropolitan Museum of Art): 72–88, JSTOR 1513695.

- Li, Chu-tsing (1980), "The Great Bronze Age of China", Art Journal 40 (1/2): 390–395, JSTOR 776607.

- Qiu, Xigui (2000), Chinese writing, trans. by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman, Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China and The Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, ISBN 978-1-55729-071-7. (English translation of Wénzìxué Gàiyào 文字學概要, Shangwu, 1988.)

- Sawyer, Ralph D.; Sawyer, Mei-chün Lee (1994), Sun Tzu's The Art of War, New York: Barnes and Noble, ISBN 978-1-56619-297-2.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1988), "Historical Perspectives on The Introduction of The Chariot Into China", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 48 (1): 189–237, JSTOR 2719276.

- Smith, Adam Daniel (2011), "The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Origins of the Calendar", in Steele, John M., Calendars and Years II: Astronomy and time in the ancient and medieval world, Oxbow Books, pp. 1–37, ISBN 978-1-84217-987-1.

- Smith, Howard (1961), "Chinese Religion in the Shang Dynasty", International Review for the History of Religions 8 (2): 142–150, doi:10.1163/156852761x00090, JSTOR 3269424.

- Sun, Guangqi (1989), 中国古代航海史 [History of Navigation in Ancient China], Beijing: Ocean Press, ISBN 978-7-5027-0532-9.

- Sun, Yan (2006), "Colonizing China's Northern Frontier: Yan and Her Neighbors During the Early Western Zhou Period", International Journal of Historical Archaeology 10 (2): 159–177, doi:10.1007/s10761-006-0005-3.

- Thorp, Robert L. (1981), "The Date of Tomb 5 at Yinxu, Anyang: A Review Article", Artibus Asiae 43 (3): 239–246, JSTOR 3249839.

- Wagner, Donald B. (1993), Iron and Steel in Ancient China, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-09632-5.

- Wang, Hongyuan 王宏源 (1993), 漢字字源入門 [The Origins of Chinese Characters], Beijing: Sinolingua, ISBN 978-7-80052-243-7.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000), Chinese history: a manual (2nd ed.), Harvard Univ Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

Further reading

- Allan, Sarah (1991), The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-9449-3.

- Allen, Herbert J. (translator) (1895), "Ssŭma Ch'ien's Historical Records, Chapter III – The Yin Dynasty", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 27 (3): 601–615, doi:10.1017/S0035869X00145083.

- Chang, Kwang-Chih (1980), Shang Civilization, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02885-7.

- Duan, Chang-Qun; Gan, Xue-Chun; Wang, Jeanny; Chien, Paul K. (1998), "Relocation of Civilization Centers in Ancient China: Environmental Factors", Ambio 27 (7): 572–575, JSTOR 4314793.

- Legge, James (translator) (1865), "The Annals of the Bamboo Books: The Dynasty of Shang", The Chinese Classics, volume 3, part 1, pp. 128–141.

- Lee, Yuan-Yuan; Shen, Sin-yan (1999), Chinese Musical Instruments, Chinese Music Monograph Series, Chinese Music Society of North America Press, ISBN 1-880464-03-9.

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 3, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-07060-7.

- Shen, Sinyan (1987), "Acoustics of Ancient Chinese Bells", Scientific American 256: 94, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0487-104.

- Timperley, Harold J. (1936), The Awakening of China in Archaeology; Further Discoveries in Ho-Nan Province, Royal Tombs of the Shang Dynasty, Dated Traditionally from 1766 to 1122 B.C..

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shang Dynasty. |

| Preceded by Xia dynasty |

Dynasties in Chinese history ca. 1600–ca. 1047 BC |

Succeeded by Zhou dynasty |