Shakespeare's handwriting

William Shakespeare's handwriting is known from six surviving signatures, all of which appear on legal documents. In addition, many scholars believe that three pages of the manuscript of the unpublished play Sir Thomas More were written by him. These are all in the handwriting style known as secretary hand, common in Shakespeare's day, but one that was beginning to be replaced by the more modern Italianate cursive script.

Serious study of Shakespeare's handwriting began in the 18th century with the pioneering scholars Edmond Malone and George Steevens. By the late nineteenth century paleographers began to make detailed study of the evidence in the hope of identifying Shakespeare's handwriting in other surviving documents. Furthermore, study of the published texts yielded indirect evidence of his handwriting quirks through apparent misreadings by printers. Over the same period, as with portraits of Shakespeare, a number of misidentifications occurred and outright forgeries were created, notably the Ireland Shakespeare forgeries in the 1790s.

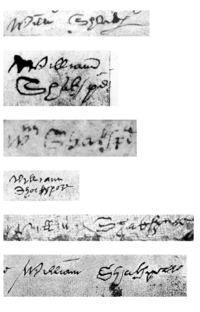

Shakespeare's signatures

Bellott v. Mountjoy deposition

12 June 1612

Blackfriars Gatehouse

conveyance

10 March 1613

Blackfriars mortgage

11 March 1616

Page 1 of will

(from 1817 engraving)

Page 2 of will

Last page of will

25 March 1616

There are six surviving signatures that are generally recognised as written by Shakespeare himself, attached to four legal documents:

- a deposition in the Bellott v. Mountjoy case, dated 11 May 1612

- the purchase of a house in Blackfriars, London, dated 10 March 1613

- the mortgage of the same house, dated 11 March 1613

- his Last Will and Testament, which contains three signatures, one on each page, dated 25 March 1616

The signatures appear as follows:

- Willm Shakp

- William Shakspēr

- Wm Shakspē

- William Shakspere

- Willm Shakspere

- By me William Shakspeare

Three of these are abbreviated versions of the surname, using breviographic conventions of the time.

That was common practice. For example Edmund Spenser sometimes wrote his name out in full (spelling his first name Edmund or Edmond), but often used the abbreviated forms "Ed: spser" or "Edm: spser".[1] The signatures on the Blackfriar's document may have been abbreviated because they had to be squeezed into the small space provided by the seal-tag, which they were legally authenticating.

The three signatures on the will were first reproduced by the 18th-century scholar George Steevens, who copied them as accurately as he could by hand and then had his drawings engraved. The facsimiles were first printed in the 1778 edition of Shakespeare's plays, edited by Steevens and Samuel Johnson.[2] The publication of the signatures led to a controversy about the proper spelling of Shakespeare's name. The paleographer Edward Maunde Thompson later criticised the Steevens' transcriptions, arguing that his original drawings were inaccurate.

The two signatures relating to the house sale were identified in 1768 and acquired by David Garrick, who presented them to Steevens' colleague Edmund Malone. By the later nineteenth century the signatures had been photographed. Photographs of these five signatures were published by Sidney Lee.[3]

The final signature, on the Bellott v. Mountjoy deposition, was discovered by 1909 by Charles William Wallace.[4] It was first published by him in the March 1910 issue of Harper's Magazine and reprinted in the October 1910 issue of Nebraska University Studies.

Montaigne

In the early 19th century a signature was found on the fly-leaf of a copy of John Florio's translation of the works of Montaigne, which reads "Willm. Shakspere". It was considered authentic by the paleographer Frederic Madden, who defended it in an article Observations on an Autograph of Shakspere and the Orthography of his name, published as a pamphlet in 1838.

By the latter part of the century opinion had moved away from support for its authenticity. By 1906 John Louis Haney could write confidently that it "is now regarded as a forgery".[5] It has had a few defenders since, but is generally viewed as inauthentic.[6]

Archaionomia

In the late 1930s a putative seventh Shakespeare signature was found in the Folger Library copy of William Lambarde's Archaionomia (1568), a collection of Anglo-Saxon laws. In 1942, Giles Dawson published a report cautiously concluding that the signature was genuine, and 30 years later he concluded that there was "an overwhelming probability that the writer of all seven signatures was the same person, William Shakespeare."[7] Nicholas Knight published a book-length study a year later with the same conclusion.[8] Sam Schoenbaum considered that the signature was more likely to be genuine than not with "a better claim to authenticity than any other pretended Shakespeare autograph," he wrote that "it is premature ... to classify it as the poet's seventh signature,"[9] Stanley Wells notes that the authenticity of both the Montaigne and Lambarde signatures have had strong support,[10] but the ascription has not gained wide academic attention nor any overwhelming consensus.

In 2012 University of Mississippi English professor Gregory Heyworth and his students used a 39-megapixel multispectral digital imaging system to enhance the signature as a first step to authenticating the signature.[11]

Handwriting analysis

The first detailed studies of Shakespeare's handwriting were made in the 19th century, when there were attempts to identify his distinctive characteristics, as distinguished from other writers using "secretary hand". As scholars noted, the task was difficult because the evidence was so thin. It was compounded by the fact that three of the known signatures were written in the last weeks of his life, when he may have been suffering from a tremor or otherwise enfeebled by illness. Even the signatures written while he was presumably in good health were created in difficult circumstances. As Edward Maunde Thompson remarked, those signed to the Blackfrairs mortgage had to be squeezed into the narrow space of the seal.[12]

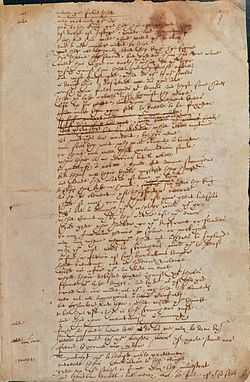

The issue became significant when debate emerged over the manuscript of the play Sir Thomas More. In 1871 Richard Simpson argued that some of the manuscript was by Shakespeare. James Spedding supported Simpson's arguments, adding that the handwriting "agrees with his signatures", and that it was written in the "ordinary character of the time."[13]

Others argued that too little was distinctive in Shakespeare's signatures to judge authorship on those grounds. Thompson intervened in the debate. He believed that the discovery of the Bellott v. Mountjoy deposition changed matters, as this signature was unconstrained. Its "fluent style" allowed us to "recover the key" to the problem. Thompson identified distinctive characteristics in Shakespeare's hand, notably the use of an Italianate long "S" in the otherwise typical secretary style, and the 'spurred a,' which is exceptionally rare.[14] After detailed examination Thompson concluded that his writing was quite "ordinary" with "few salient features for instant recognition", apart from the "s" and an unusual formation of the "k". Nevertheless, after a detailed study of every letter formation in the More script, Thompson concluded that it was written by Shakespeare on the basis that identifiable quirks in the signatures were repeated in the manuscript.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Albert Charles Hamilton (ed), The Spenser Encyclopedia, University of Toronto Press, 1990, p. 346.

- ↑ Edward Maude Thompson, Shakespeare's Handwriting: A Study, Oxford, Clarendon, 1916. p. x.

- ↑ Sidney Lee, Shakespeare's Handwriting: Facsimiles of the Five Authentic Autograph Signatures, London, Smith Elder, 1899.

- ↑ Wallace, Charles William, "Shakespeare and his London Associates," Nebraska University Studies, October 1910.

- ↑ John Louis Haney, The Name of William Shakespeare, Egerton, 1906, pp. 27–30.

- ↑ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion, 1550–1950, Funk & Wagnalls, New York, 1952 pp. 209, 424.

- ↑ Dawson, Giles. "A Seventh Signature for Shakespeare." Shakespeare Quarterly 43 (Spring 1992): 72–79, p. 79.

- ↑ Knight, W. Nicholas. Shakespeare's Hidden Life: Shakespeare at the Law 1585-1595. New York: Mason & Lipscomb, 1973.

- ↑ Schoenbaum, Samuel. William Shakespeare: Records and Images. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981, p. 109.

- ↑ Wells, Stanley (2001). "Shakespeare's signatures" in Dobson, Michael, and Stanley Wells, eds. Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford Companions to Literature. Oxford University Press. pp. 431. ISBN 978-0-19-811735-3.

- ↑ Pappas, Stephanie. "Restored Scribble May Be Shakespeare's Signature". Live Science. TechMediaNetwork. 14 April 2012.

- ↑ E.M. Thompson, Shakespeare's Handwriting: A Study, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1916, p. 6-7.

- ↑ Notes and Queries, 4th Series, 21 September 1872.

- ↑ S. Schoenbaum, A Documentary Life, Oxford University Press/Scolar Press, 1975 p.157.

- ↑ Schoenbaum, A Documentary Life, p.158:'The cumulative evidence for Shakespeare's hand in the 'More' fragment may not be sufficient to shake away all doubts – but who else in this period formed an a with a horizontal spur, spelt silence as scilens, and had identical associative patterns of thought and image? All roads converge on Shakespeare'.

External links

- "New Shakespeare Discoveries: Shakespeare as a Man among Men" by Charles William Wallace. Article at Google Books from the March 1910 issue of Harper's Magazine announcing the discovery of Shakespeare's deposition signature from the Bellott-Mountjoy suit.

- Spectral Imaging of Shakespeare’s “Seventh Signature” from The Collation.

.png)