Sexual Preference (book)

|

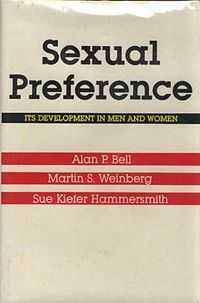

The 1981 Indiana University Press edition | |

| Author | Alan P. Bell, Martin S. Weinberg, Sue Kiefer Hammersmith |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Psychology |

| Published | 1981 (Indiana University Press) |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 242 |

| ISBN | 0-253-16673-X |

Sexual Preference: Its Development in Men and Women is a 1981 book about the development of sexual orientation by Alan P. Bell, Martin S. Weinberg, and Sue Kiefer Hammersmith,[1] a publication of the Institute for Sex Research.[2]

Together with its separately published Statistical Appendix, Sexual Preference was the culmination of a series of books including Homosexuality: An Annotated Bibliography (1972) and Homosexualities: A Study of Diversity Among Men and Women (1978), both authored jointly by Bell and Weinberg.[3][4][5] Based on interviews with subjects in the San Francisco Bay Area, Bell, Weinberg and Hammersmith found almost no correlation between early family experience and adult sexual orientation, and concluded that heterosexuality and homosexuality have a biological basis. Their conclusions were criticized on methodological and other grounds.

Study and findings

In 1970, Bell et al., researchers affiliated with the Alfred Kinsey Institute for Sex Research, surveyed 686 gay men, 293 lesbians, 337 heterosexual men and 140 heterosexual women living in San Francisco,[6] avoiding the biases of many previous studies, which had drawn their samples from unrepresentative sources such as psychotherapy patients or prison populations.[7] Gay and lesbian volunteers were obtained through recruiting through advertisements in gay gathering places and by word of mouth. Heterosexual subjects were obtained using random sampling techniques. Subjects were interviewed in their own homes for three to five hours. They were asked about two hundred questions, some open-ended, some specifying a limited number of possible answers.[6]

The following criteria for homosexuality and heterosexuality were used: "Respondents were asked to rate their sexual feelings and behaviors on the seven-point Kinsey Scale, which ranges from 'exclusively heterosexual' (a score of 0) to 'exclusively homosexual' (a score of 6). Respondents' sexual feelings scores were then averaged with their sexual behaviors scores. Those with a combined score of 2 or more were classified as homosexual; those with a combined score of less than 2, heterosexual."[8]

Bell et al. concluded that most previous hypotheses about the origins of homosexuality were mistaken. These theories included the views of Sigmund Freud, who claimed that homosexuality was caused by unresolved difficulties with the Oedipus complex, and those of his successors, who pointed to possessive mothers and remote fathers. Bell et al. discovered that boys who grow up with dominant mothers and weak fathers have nearly the same chance of becoming homosexual as boys who grow up in "ideal" family settings.[9] There was no difference between heterosexual men and gay men in the strength of attachment to their mothers, and while Bell et al. found that unfavorable relationships with fathers seem to be connected with gender non-conformity and early homosexual experience, the connection to adult sexual orientation was not strong. The results for women were similar: parental relationships, traits, and identification were not critical factors in the development of female homosexuality.[6] Bell et al. found that lack of friends in childhood was not a significant factor (the small extent to which homosexual men and women were less involved with peers while growing up was more a result of feeling different than a cause), and that there was no evidence that men who were labelled effeminate became homosexual for that reason. They also concluded that traumatic experiences with the opposite sex, rape, punishment by parents for sex play, and seduction by a person of the same sex played no role in the development of sexual orientation, and that most people's sexual identities are determined by the time they reach adolescence.[9]

Their data suggested that early sexual experience does not play a significant role, though it might have some secondary role: "childhood and adolescent sexual expression by and large reflect rather than determine a person's underlying sexual [orientation]...Sexual experiences with members of the same sex were common among both the homosexual and the heterosexual respondents; so were experiences with members of the opposite sex. What differs markedly between the homosexual and heterosexual respondents, and what appears to be more important in signaling eventual sexual [orientation]...is the way respondents felt sexually, not what they did."[10] "Recruitment" played little if any role.[9]

The data did support gender nonconformity theories: boys who became homosexual had been less stereotypically masculine than boys who became heterosexual. Fewer of the homosexual men remembered themselves as having been very masculine while growing up, and more homosexual than heterosexual respondents recalled dislike for typical boys' activities and enjoyment of those they thought were "for girls." These kinds of gender non-conformity were directly related to experiencing both homosexual activities and homosexual arousal before age 19, a sense of an explicitly sexual difference from other boys, and a delay of feelings of sexual attraction to girls, as well as adult homosexuality. Similarly, among females, childhood gender non-conformity appears to have been related to homosexual feelings and behaviors, both while growing up and in adulthood.[11]

In conclusion, Bell at al. argued for the naturalness of homosexuality and greater social tolerance.[9]

Scholarly reception

Sexual Preference is one of the most frequently cited retrospective studies relating to sexual orientation.[6] However, some early reviews of the work were highly critical.[12][13][14]

Sociologist John Gagnon, writing in The New York Times, noted that Sexual Preference would inevitably be received as a political and moral statement as much as a scientific study, and that its conclusion that homosexuality and heterosexuality have a biological basis, based on its authors finding that there is almost no correlation between adult sexual preference and early family experience, was controversial. Gagnon criticized Bell et al.'s methodology on several grounds, arguing that its exclusive use of path analysis emphasized differences rather than similarities between heterosexual and homosexual patterns of development, and that its reliance upon adult recall of early childhood feelings was inconsistent with all recent research on memory. Gagnon criticized Bell et al.'s conclusion that heterosexuality and homosexuality have a biological basis as being based upon weak and largely disconfirmed studies, and also as inconsistent with the idea that they are "preferences".[14]

Psychologist Clarence Arthur Tripp, writing in the Journal of Sex Research, commented that Sexual Preference would likely be seen as "a shock and a disappointment", writing that it abandoned many of Alfred Kinsey's methods and conclusions, and in some cases even misrepresented them. Tripp disputed Bell et al.'s conclusion that the origins of sexual orientation were biological, and criticized them for ignoring the work of sex researchers such as Frank Beach, as well as for citing low quality and unreplicated hormone studies.[13] Ira L. Reiss, writing in Contemporary Sociology, suggested that Sexual Preference suffers from several serious flaws. According to Reiss, Bell et al.'s sample, while broader than many previous ones utilized in similar studies, was not representative of any larger population. Reiss believed that given this and other problems, such as the use of "vague open-ended questions", and the problems involved in adult recall of early childhood feeling, there was no way in which Sexual Preference could definitively resolve the issues it explored. In his view, its authors tended to minimize the importance of the predictor variables they used to test psychoanalytic and other theories.[12]

John P. DeCecco, Professor of Psychology and Human Sexuality at San Francisco State University, dismissed both Sexual Preference and Bell and Weinberg's previous study Homosexualities, writing that while they "purported to be definitive studies of homosexuality", they were "hurried retreats behind computer statistics which cover their theoretical nakedness." DeCecco found both books to be examples of the "theoretical blindness" that in his view has dominated research on homosexuality in the United States.[2]

Historian and sociologist Jeffrey Weeks criticizes Bell et al. for concluding that if a social or psychological explanation of homosexuality cannot be found, then a biological explanation must exist. Weeks considers their argument "basically a rhetorical device", writing that it results in, "an intellectual closure which obstructs further questioning."[15]

Timothy F. Murphy calls Sexual Preference an important study of homosexuality, commenting that it is useful despite its limitations and possible flaws and incompleteness.[16]

John Heidenry considers Sexual Preference perhaps the most important book published on sexuality in the early 1980s. He observes that Bell et al.'s conclusion that homosexuality may have a biological basis placed them in fundamental opposition to Kinsey's views, and that in attempting to find a universal explanation of homosexuality they ignored much research that correlated the origins of same-sex preference with factors such as time of puberty, the amount of early sex, and masturbatory patterns.[7]

Kenneth Zucker and Susan Bradley, who call Sexual Preference a "classic study", write that its data were consistent with those of previous clinical research, including Irving Bieber's Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals. They suggest that Bell et al. borrowed from the psychoanalytic perspective that saw homosexuality as a mental disorder and explained it in terms of family dynamics, which was dominant in the late 1960s when their study was being planned, in conducting aspects of their inquiry. Zucker and Bradley believe that Bell et al.'s interpretation of their data was affected by political correctness, and that they minimized the importance of data that suggested a departure from an ideal of optimal functioning in homosexual men, though they note that this was also in part an objective interpretation of weak effects.[17]

Philosopher Edward Stein writes in his The Mismeasure of Desire (1999), that while Bell et al.'s study has been criticized on various grounds, its conclusions with respect to experiential theories seem to have been confirmed and accepted, and that many other retrospective studies have been conducted on childhood gender non-conformity partly because of its findings on the subject.[6]

See also

|

|

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Bell 1981. p. iv.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 DeCecco 1982. p. 282.

- ↑ Bell 1981. p. 238.

- ↑ Bell 1978. p. 4.

- ↑ Bell 1972. p. iv.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Stein 1999. p. 235.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Heidenry 1997. pp. 272–273.

- ↑ Bell 1981. p. 32.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Heidenry 1997. p. 273.

- ↑ Stein 1999. pp. 235-236.

- ↑ Stein 1999. p. 236.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Reiss 1982. pp. 455–456.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Tripp 1982. pp. 183-186.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Gagnon 1981.

- ↑ Weeks 1993. p. 120.

- ↑ Murphy 1997. pp. 60, 240.

- ↑ Zucker 1995. pp. 240-241.

Bibliography

- Books

- Bell, Alan P.; Weinberg, Martin S. (1972). Homosexuality: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-014541-2.

- Bell, Alan P.; Weinberg, Martin S. (1978). Homosexualities: A Study of Diversity Among Men and Women. South Melbourne: The Macmillan Company of Australia. ISBN 0-333-25180-6.

- Bell, Alan P.; Weinberg, Martin S.; Hammersmith, Sue Kiefer (1981). Sexual Preference: Its Development in Men and Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-16673-X.

- Heidenry, John (1997). What Wild Ecstasy: The Rise and Fall of the Sexual Revolution. Kew: William Heinemann Australia. ISBN 0-85561-689-X.

- Murphy, Timothy F. (1997). Gay Science: The Ethics of Sexual Orientation Research. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10849-4.

- Stein, Edward (1999). The Mismeasure of Desire: The Science, Theory, and Ethics of Sexual Orientation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514244-6.

- Weeks, Jeffrey (1993). Sexuality and its discontents: Meanings, myths and modern sexualities. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04503-7.

- Zucker, Kenneth; Bradley, Susan J. (1995). Gender Identity Disorder and Psychosexual Problems in Children and Adolescents. New York: The Guilford Press. ISBN 0-89862-266-2.

- Journals

- DeCecco, John P. (1982). Davis, Clive M., ed. "The Journal of Sex Research, August 1982, Vol 18, No. 3". Lake Mills, Iowa: The Society for the Scientific Study of Sex.

- Reiss, Ira L. (1982). D'Antonio, William V., ed. "Contemporary Sociology, July 1982, Vol 11, No. 4". New York: American Sociological Association.

- Tripp, Clarence (1982). Davis, Clive M., ed. "The Journal of Sex Research, May 1982, Vol 18, No. 2". Lake Mills, Iowa: The Society for the Scientific Study of Sex.

- Online articles

- Gagnon, John. "Searching for the childhood of eros". Retrieved 2013-09-15.