Settlement of the Americas

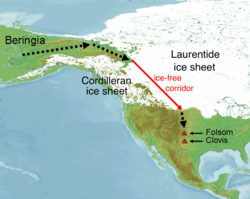

!["Three maps of prehistoric North America. (A) then gradual population expansion of the Amerind ancestors from their East Central Asian gene pool (blue arrow). (B) Proto-Amerind occupation of Beringia with little to no population growth for ≈20,000 years. (C) Rapid colonization of the New World by a founder group migrating southward through the ice-free, inland corridor between the eastern Laurentide and western Cordilleran Ice Sheets (green arrow) and/or along the Pacific coast (red arrow). In (B), the exposed seafloor is shown at its greatest extent during the last glacial maximum at ≈20–18 kya [25]. In (A) and (C), the exposed seafloor is depicted at ≈40 kya and ≈16 kya, when prehistoric sea levels were comparable. A scaled-down version of Beringia today (60% reduction of A–C) is presented in the lower left corner. This smaller map highlights the Bering Strait that has geographically separated the New World from Asia since ≈11–10 kya."](../I/m/Journal.pone.0001596.g004.png)

The question of how, when, where and why humans first entered the Americas is of intense interest to archaeologists and anthropologists, and has been a subject of heated debate for centuries.[1] Several models for the Paleo-Indian settlement of the Americas have been proposed by various academic communities. Modern biochemical techniques, as well as more thorough archaeology, have shed progressively more light on the subject.

Current understanding of human migration to and throughout the Americas derives from advances in four interrelated disciplines: linguistics, archeology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis. While there is general agreement that the Americas were first settled from Asia by people who migrated slowly across Beringia, over many generations, the pattern of migration, its timing, and the place of origin in Asia of the peoples who migrated to the Americas remains unclear.[2][3] In recent years, researchers have sought to use familiar tools to validate or reject established theories, such as Clovis first.[4] As new discoveries come to light, past hypotheses are reevaluated and new theories constructed. The archeological evidence suggests that the Paleo-Indians' first "widespread" habitation of the Americas occurred during the end of the last glacial period or, more specifically, what is known as the late glacial maximum, around 16,500–13,000 years ago.[5]

Understanding the debate

In the early 21st century, the chronology of migration models is divided into two general approaches.[6][7] The first is the short chronology theory, based on the concept that the first movement beyond Alaska into the New World occurring no earlier than 15,000–17,000 years ago, followed by successive waves of immigrants.[8][9] The second belief is the long chronology theory, which proposes that the first group of people entered the Americas at a much earlier date, possibly 21,000–40,000 years ago,[10][11] with a much later mass secondary wave of immigrants.[12][13][14]

One factor fueling the debate is the discontinuity of archaeological evidence between North and South American Paleo-Indian sites. A roughly uniform techno-complex pattern, known as Clovis, appears in North and Central American sites from at least 13,500 years ago onwards.[15] South American sites of equal antiquity do not share the same consistency and exhibit more diverse cultural patterns. Archaeologists conclude that the "Clovis-first", and Paleo-Indian time frame do not adequately explain complex lithic stage tools appearing in South America. Some theorists seek to develop a migration model that integrates both North and South American archaeological records.

| Dates BCE | Beringia "Land Bridge" | Coastal route | Mackenzie Corridor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 38,000–34,000 | accessible (open) | open | closed |

| 34,000–30,000 | submerged (closed) | open | open |

| 30,000–22,000 | accessible (open) | closed | open |

| 22,000–15,000 | accessible (open) | open | closed |

| 15,000–today | submerged (closed) | open | open |

Indigenous Amerindian genetic studies indicate that the "colonizing founders" of the Americas emerged from a single-source ancestral population that evolved in isolation, likely in Beringia.[17][18][19][20][21] Age estimates based on Y-chromosome micro-satellite place diversity of the American Haplogroup Q1a3a (Y-DNA) at around 10,000 to 15,000 years ago.[7][22] This does not address if there were any previous failed colonization attempts by other genetic groups, as genetic testing can only address the current population's ancestral heritage.[7]

Migrants from northeastern Asia could have walked to Alaska with relative ease when Beringia was above sea level. But traveling south from Alaska to the rest of North America may have posed significant challenges. The two main possible southward routes proposed for human migration are: down the Pacific coast; or by way of an interior passage (Mackenzie Corridor) along the eastern flank of the Rocky Mountains.[20] When the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets were at their maximum extent, both routes were likely impassable. The Cordilleran sheet reached across to the Pacific shore in the west, and its eastern edge abutted the Laurentide, near the present border between British Columbia and Alberta.

Geological evidence suggests that the Pacific coastal route was open for overland travel before 23,000 years ago and after 15,000 years ago. During the coldest millennia of the last ice age, roughly 23,000 to 19,000 years ago, lobes of glaciers hundreds of kilometers wide flowed down to the sea.[18] Deep crevasses scarred their surfaces, making travel across them dangerous. Even if people traveled by boat—a claim for which there is no direct archaeological evidence, as sea level rise has hidden the old coastline—the journey would have been difficult due to abundant icebergs in the water. Around 15,000 to 13,000 years ago, the coast is presumed to have been ice-free. Additionally, by this time the climate had warmed, and lands were covered in grass and trees. Early Paleo-Indian groups could have readily replenished their food supplies, repaired clothing and tents, and replaced broken or lost tools.[18]

Coastal or "watercraft" theories have broad implications, one being that Paleo-Indians in North America may not have been purely terrestrial big-game hunters, but instead were already adapted to maritime or semi-maritime lifestyles.[14] Additionally, it is possible that "Beringian" (western Alaskan) groups migrated into the northern interior and coastlines only to meet their demise during the last glacial maximum, approximately 20,000 years ago,[23] leaving evidence of occupation in specific localized areas. However, they would not be considered a founding population unless they had managed to migrate south, populate and survive the coldest part of the last ice age.[24]

Genetics and blood type

By the 1920s studies indicated that blood type O was predominant in pre-Columbian populations, with a small admixture of type A in the north. Further blood studies combining statistics and genetic research were pioneered by Luigi Cavalli-Sforza and applied to population migrations predating historical records. This led Jacob Bronowski to assert in 1973 (in The Ascent of Man) that there were at least two separate migrations:

"I can see no sensible way of interpreting that but to believe that a first migration of a small, related kinship group (all of blood group O) came into America, multiplied, and spread right to the South. Then a second migration, again of small groups, this time containing either A alone or both A and O, followed them only as far as North America."[25]

Modern Amerindian genetics studies focus primarily on human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups (yDNA haplogroups) and human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups (mtDNA haplogroups). Recent years have seen the development of high resolution analytical techniques, which have been applied to DNA samples from modern Native Americans and Asian populations regarded as related to their potential source populations,[18] and to samples of fossil DNA in the Americas and in Asia.[26][27] The genetic pattern emerging shows two very distinctive genetic episodes occurred, first with the initial peopling of the Americas, and secondly with European colonization of the Americas.[7][28][29] The former is the determinant factor for the number of gene lineages, zygosity mutations and founding haplotypes present in today's indigenous Amerindian populations.[28]

One genetic model (illustrated) proposes that human settlement of the New World occurred in stages from Beringia, with an initial layover for the small founding population.[7][18] The model may be limited by a more recent analysis suggesting expansion of Haplogroups C and D from southern Siberia and eastern Asia, respectively, during the time interval of the proposed layover[30] and evidence for the presence of Subhaplogroups D1[26] and D4h3[31] in coastal Asia. Further constraints may be added by the use of age-dated fossil DNA to calibrate the rates of molecular evolution that the time elements of such models are dependent upon.[27]

The micro-satellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonization of the region.[32] The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) mutations, but are distinct from other indigenous Amerindians with various mtDNA and autosomal DNA (atDNA) mutations.[33][34][35] This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations.[36][37]

Land bridge theory

Also known as the Bering Strait Theory or Beringia theory, the Land Bridge theory has been widely accepted since the 1930s. The idea was first postulated in a rudimentary fashion in 1590 by the Jesuit scholar José de Acosta.[38] This model of migration into the New World proposes that people migrated from Siberia into Alaska, tracking big game animal herds. They were able to cross between the two continents by a land bridge called the Bering Land Bridge, which spanned what is now the Bering Strait, during the Wisconsin glaciation, the last major stage of the Pleistocene beginning around 50,000 years ago and ending some 10,000 years ago when ocean levels were 60 metres (200 ft) lower than today.[39] This information is gathered using oxygen isotope records from deep-sea cores. An exposed land bridge that was at least 1,000 miles (1,600 km) wide existed between Siberia and the western coast of Alaska. While land travel was possible between Siberia and Alaska through Beringia, there is no consensus on the timing of the first human settlement on the Alaskan side. Most datable archaeosites postdate the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and the reliability of earlier dates at the Bluefish Cave and Old Crow sites in the Yukon Territory has been called into question.[40][41] Arguments for a longer occupation of Beringia, up to 15 to 20,000 years prior to the post-LGM radiation of the population out of Beringia, arise from models of genetic "clocks" started when Beringian populations became isolated from their source populations in Asia.[42][43] Some question whether the rates of such genetic "clocks" are sufficiently constrained to provide meaningful age estimates.[27] In the "short chronology" version, from the archaeological evidence gathered, it was concluded that this culture of big game hunters crossed the Bering Strait at least 12,000 years ago and could have eventually reached the southern tip of South America by 11,000 years ago.

Crossings by foot of the Bering Sea, however, are also possible when the sea is frozen.[44]

The physical environment of the northwestern North American coast during early deglaciation

During the LGM, the eustatic sea level was some 120M lower than today due to the volume of water stored in the world's glaciers. Significant areas of the coast were fronted by coastal plains, in contrast to today's environment, and some islands, such as Haida Gwaii, were connected to the mainland by a coastal plain.[39] Glaciation along the coast had three types of sources: large outlet glaciers to the main body of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, locally-sourced glaciers on the mainland, and glaciers sourced from from the islands. Glaciers commonly coalesced into piedmont glaciers on the coastal plain. With warming of the climate initiating around 18k years BP, the smaller, locally-sourced glaciers were the first to respond. The seaward sides of the islands were soon ice-free and the coastal plains became expanses of ice-free land crossed by the larger Cordilleran glaciers.[39] So even as the Cordilleran Ice Sheet was advancing rapidly through the Puget Lowlands of Washington State at 17.35k to 16.8k years BP (14.5k to 14k 14C years BP),[45] the northern coast was rapidly deglaciating. Also significant is the rapid deglaciation of the Alaskan Coast Ranges, which established ice-free coastal refugia in the Cook Inlet - Kenai Peninsula area by 17.35k years BP (14.5k 14C years BP) and opened the ice barrier to the interior of Alaska in the Copper River area by 16.2k years BP (13.5k 14C years BP)[46] While the coast was becoming more accommodating to human habitation during deglaciation, significant uncertainty remains regarding disruption of land migration routes by Cordilleran ice, particularly if late local surges of Cordilleran glaciers occurred during that period. The ice-choked straits of Georgia, between Vancouver Island and the mainland, would have remained a barrier to land-borne migration at least as recently as 15.6k years BP (13k 14C years BP)and possibly later.[47]

The problems associated with finding archaeological evidence for migration during a period of lowered sea level are well known.[48][39][49] Sites related to the first migration are usually submerged, so the location of such sites is obscured. Certain types of evidence dependent on organic material, such as radiocarbon dating, may be destroyed by submergence. Wave action can destroy site structures and scatter artifacts along a prograding shoreline. Additionally, Pacific coastal conditions tend to be unstable due to steep unstable terrain, earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes. Strategies for finding earliest migration sites include identifying potential sites on submerged paleoshorelines, seeking sites in areas uplifted either by tectonics or isostatic rebound, and looking for riverine sites in areas that may have attracted coastal migrants.[48][39][50] Otherwise, coastal archaeology is dependent on secondary evidence related to lifestyles and technologies of maritime peoples from sites similar to those that would be associated with the original migration.

Synopsis

At some point during the last Ice Age, about 17,000 years ago, as the ice sheets advanced and sea levels fell, people first migrated from the Eurasian landmass to the Americas. These nomadic hunters were following game herds from Siberia across what is today the Bering Strait into Alaska, and then gradually spread southward. Based upon the distribution of Amerind languages and language families, a movement of tribes along the Rocky Mountain foothills and eastward across the Great Plains to the Atlantic seaboard is assumed to have occurred at least some 13,000 to 10,000 years ago.

Clovis culture

This big game-hunting culture has been labeled the Clovis culture, and is primarily identified by its artifacts of fluted projectile points. The culture received its name from artifacts found near Clovis, New Mexico, the first evidence of this tool complex, excavated in 1932. The Clovis culture ranged over much of North America and appeared in South America. The culture is identified by a distinctive Clovis point, a flaked flint spear-point with a notched flute by which it was inserted into a shaft. It could be removed from the shaft for traveling. This flute is one characteristic that defines the Clovis point complex.

Dating Clovis materials has been by association with animal bones and by carbon dating. Recent reexaminations of Clovis materials using improved carbon-dating methods produced results of 11,050 and 10,800 radiocarbon years B.P. (before present). This evidence suggests that the culture flowered somewhat later and for a shorter period of time than previously believed. Michael R. Waters of Texas A&M University in College Station and Thomas W. Stafford Jr., proprietor of a private-sector laboratory in Lafayette, Colorado and an expert in radiocarbon dating, attempted to determine the dates of the Clovis period. The heyday of Clovis technology has typically been set between 11,500 and 10,900 radiocarbon years B.P. (The radiocarbon calibration is disputed for this period, but the widely used IntCal04 calibration puts the dates at 13,300 to 12,800 calendar years B.P.). In a controversial move, Waters and Stafford conclude that no fewer than 11 of the 22 Clovis sites with radiocarbon dates are "problematic" and should be disregarded—including the type site in Clovis, New Mexico. They argue that the datable samples could have been contaminated by earlier material. This contention was considered highly controversial by many in the archaeological community.

In 2014, the autosomal DNA of a 12,500+-year-old infant from Montana was sequenced.[51][52][53][54] The DNA was taken from a skeleton referred to as Anzick-1, found in close association with several Clovis artifacts. Comparisons showed strong affinities with DNA from Siberian sites, and virtually ruled out any close affinity with European sources (the so-called "Solutrean hypothesis"). The DNA also showed strong affinities with all existing Native American populations, which indicated that all of them derive from an ancient population that lived in or near Siberia, the Upper Palaeolithic Mal'ta population.[54] The data indicate that Anzick-1 is from a population directly ancestral to present South American and Central American Native American populations, ruling out hypotheses which posit that invasions subsequent to the Clovis culture overwhelmed or assimilated previous migrants into the Americas. Anzick-1 is less closely related to present North American Native American populations, suggesting an early divergence between North American and Central plus South American populations, with the North American populations being basal to the rest.[54]

Problems with Clovis migration models

Significant problems arise with the Clovis migration model. If Clovis people radiated south after entering the New World and eventually reached the southern tip of South America by 11,000 years ago, this leaves only a short time span to populate the entire hemisphere.[55] Another complication for the Clovis-only theory arose in 1997, when a panel of authorities inspected the Monte Verde site in Chile. They concluded that the radiocarbon evidence predates Clovis sites in the North American Midwest by at least 1,000 years.[56] This supports the theory of a primary coastal migration route people used to move south along the coastline faster than those who migrated inland into the central areas of the Americas. Many excavations have uncovered evidence that subsistence patterns of early Americans included foods such as turtles, shellfish, and tubers. This is a change of diet from the big game mammoths, long-horn bison, horse, and camels that early Clovis hunters apparently followed east into the New World.

At the Topper archaeological site (located along the banks of the Savannah River near Allendale, South Carolina) investigated by University of South Carolina archaeologist Dr. Albert Goodyear, charcoal material recovered in association with purported human artifacts returned radiocarbon dates of up to 50,000 years before the present (BP). This would indicate the presence of humans well before the last glacial period. Considerable doubt over the validity of these findings has been raised by many other researchers, and the pre-Clovis Topper dates remain controversial. Charcoal could have originated from forest fires, and the crude stone artifacts may be misinterpreted geofacts.

Pre-Clovis dates have been claimed for several sites in South America, but these early dates have not been verified unequivocally.

Discoveries in 2002 and 2003 of human coprolites (fossilized feces)[57] as well as hunting tools found deeply buried in the Paisley Caves in Oregon indicate the presence of humans in North America as much as 1,200 years prior to the Clovis culture.[58][59][60]

Watercraft migration theories

Earlier finds have led to a pre-Clovis culture theory encompassing different migration models with an expanded chronology to supersede the "Clovis-first" theory.

Pacific coastal models

Pacific models propose that people first reached the Americas via water travel, following coastlines from northeast Asia into the Americas. Coastlines are unusually productive environments because they provide humans with access to a diverse array of plants and animals from both terrestrial and marine ecosystems. While not exclusive of land-based migrations, the Pacific 'coastal migration theory' helps explain how early colonists reached areas extremely distant from the Bering Strait region, including sites such as Monte Verde in southern Chile and Taima-Taima in western Venezuela. Two cultural components were discovered at Monte Verde near the Pacific Coast of Chile. The youngest layer is radiocarbon dated at 12,500 radiocarbon years (~14,000 cal BP) and has produced the remains of several types of seaweeds collected from coastal habitats. The older and more controversial component may date back as far as 33,000 years, but few scholars currently accept this very early component.

Other coastal models, dealing specifically with the peopling of the Pacific Northwest and California coasts, have been advocated by archaeologists Knut Fladmark, Roy Carlson, James Dixon, Jon Erlandson, Ruth Gruhn, and Daryl Fedje. In a 2007 article in the Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, Erlandson and his colleagues proposed a corollary to the coastal migration theory—the "kelp highway hypothesis"—arguing that productive kelp forests supporting similar suites of plants and animals would have existed near the end of the Pleistocene around much of the Pacific Rim from Japan to Beringia, the Pacific Northwest, and California, as well as the Andean Coast of South America. Once the coastlines of Alaska and British Columbia had deglaciated about 16,000 years ago, these kelp forest (along with estuarine, mangrove, and coral reef) habitats would have provided an ecologically similar migration corridor, entirely at sea level, and essentially unobstructed.

East Asians: Paleoindians of the coast

The boat-builders from Southeast Asia may have been one of the earliest groups to reach the shores of North America. One theory suggests people in boats followed the coastline from the Kurile Islands to Alaska down the coasts of North and South America as far as Chile [2 62; 7 54, 57]. The Haida nation on the Queen Charlotte Islands off the coast of British Columbia may have originated from these early Asian mariners between 25,000 and 12,000. Early watercraft migration would also explain the habitation of coastal sites in South America such as Pikimachay Cave in Peru by 20,000 years ago and Monte Verde in Chile by 13,000 years ago [6 30; 8 383].

- "'There was boat use in Japan 20,000 years ago,' says Jon Erlandson, a University of Oregon anthropologist. 'The Kurile Islands (north of Japan) are like stepping stones to Beringia,' the then continuous land bridging the Bering Strait. Migrants, he said, could have then skirted the tidewater glaciers in Canada right on down the coast." [7 64]'

Atlantic coastal model

Archaeologists Dennis Stanford and Bruce Bradley champion the coastal Atlantic route. Their Solutrean Hypothesis is also based on evidence from the Clovis complex, but instead traces the origins of the Clovis toolmaking style to the Solutrean culture of Ice Age Western Europe.[61] The theory suggests that early European people (or peoples) may have been among the earliest settlers of the Americas.[62][63] Citing evidence that the Solutrean culture of prehistoric Europe may have provided the basis for the tool-making of the Clovis culture in the Americas, the theory suggests that Ice Age Europeans migrated to North America by using skills similar to those possessed by the modern Inuit peoples and followed the edge of the ice sheet that spanned the Atlantic. The hypothesis rests upon particular similarities in Solutrean and Clovis technology that have no known counterparts in Eastern Asia, Siberia or Beringia, areas from which, or through which, early Americans are known to have migrated. Most professionals discount the theory for a variety of reasons—including the fact that the differences between the two tool-making traditions far outweigh the similarities, the several thousand miles of the Atlantic Ocean they would have had to cross, and the 5,000-year-span that separates the two cultures.[64][65] Genetic studies of Native American populations have also shown that the Solutrean theory is unlikely, showing instead that the five main mtDNA haplogroups found in the Americas were all part of one gene pool migration from Asia.[66]

Problems with evaluating coastal migration models

The coastal migration models provide a different perspective on migration to the New World, but they are not without their own problems. One of the biggest problems is that global sea levels have risen over 120 metres (390 ft)[67] since the end of the last glacial period, and this has submerged the ancient coastlines that maritime people would have followed into the Americas. Finding sites associated with early coastal migrations is extremely difficult—and systematic excavation of any sites found in deeper waters is challenging and expensive. On the other hand, there is evidence of marine technologies found in the hills of California's Channel Islands, circa 10,000 BCE.[68] If there was an early pre-Clovis coastal migration, there is always the possibility of a "failed colonization". Another problem that arises is the lack of hard evidence found for a "long chronology" theory. No sites have yet produced a consistent chronology older than about 12,500 radiocarbon years (~14,500 calendar years) , but research has been limited in South America related to the possibility of early coastal migrations.

Other hypotheses

The Solutrean hypothesis: Europe to America in the Paleolithic

Archaeologists Dennis Stanford and Bruce Bradley champion their Solutrean Hypothesis based on similarities between the Paleolithic Solutrean culture of Western Europe and the Clovis culture of the postglacial Americas. It hypothesizes the Solutrean culture of Western Europe as the source of the Clovis culture.[69] The theory suggests that early European people (or peoples) may have been among the earliest settlers of the Americas.[70][71] The theory suggests that late Pleistocene Europeans migrated to North America by using skills similar to those possessed by the modern Inuit peoples and followed the edge of the ice sheet that spanned the Atlantic. The hypothesis rests upon particular similarities in Solutrean and Clovis technology that have no known counterparts in Eastern Asia, Siberia or Beringia, areas from which, or through which, early Americans are known to have migrated. Most professionals discount the theory for a variety of reasons—including the fact that the differences between the two tool-making traditions far outweigh the similarities, the complete lack of evidence that Paleolithic Europeans had the means to cross an open ocean, and the 5,000-year-span that separates the two cultures.[72][73] Genetic studies of Native American populations have also shown that the Solutrean theory is unlikely, showing instead that the five main mtDNA haplogroups found in the Americas were all part of one gene pool migration from Asia.[74]

Pre-Columbian contact from other continents

Theories of pre-Columbian contact unrelated to the initial peopling of the Americas are not within the scope of this article, regardless of whether they are based on science or legend. The vast majority of pre-Columbian contact hypotheses are claims based on circumstantial or ambiguous evidence. The scientific responses to such pre-Columbian contact claims range from consideration in peer-reviewed publications to outright dismissal as fringe science or pseudoarcheology.[75][76]

Notes and references

- ↑ Timothy R. Pauketat (2012). The Oxford Handbook of North American Archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-19-538011-8.

- ↑ Goebel, Ted; Waters, Michael R.; O'Rourke, Dennis H. (2008). "The Late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas" (PDF). Science 319 (5869): 1497–1502. doi:10.1126/science.1153569. PMID 18339930. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- ↑ "Pause Is Seen in a Continent’s Peopling". New York Times. 13 Mar 2014.

- ↑ Gremillion, David H.; Auton, Adam; Falush, Daniel (2008-09-25). "Archaeolog: Pre Siberian Human Migration to America: Possible validation by HTLV-1 mutation analysis". PLoS Genetics (Traumwerk.stanford.edu) 4 (5): e1000078. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000078. PMID 18497854. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ Bonatto, Sandro L.; Salzano, Francisco M. (1997). "A single and early migration for the peopling of the Americas supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 94 (5): 1866–1871. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. PMC 20009. PMID 9050871.

- ↑ Phillip M. White (2006). American Indian chronology: chronologies of the American mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-313-33820-5. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man - A Genetic Odyssey (DIGITISED ONLINE BY GOOGLE BOOKS). Random House. pp. 138–140. ISBN 0-8129-7146-9. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ↑ "Chaw joins poop in archaeology arsenal". University of Wisconsin.

- ↑ Axelrod, Alan (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to American History. Alpha Books. ISBN 0-02-864464-6. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- ↑ "Introduction". Government of Canada. Parks Canada. 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago like the U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago

- ↑ "Pleistocene Archaeology of the Old Crow Flats". Vuntut National Park of Canada. 2008. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

However, despite the lack of this conclusive and widespread evidence, there are suggestions of human occupation in the northern Yukon about 24,000 years ago, and hints of the presence of humans in the Old Crow Basin as far back as about 40,000 years ago.

- ↑ "Atlas of the Human Journey". National Genographic.

- ↑ "First Americans". Southern Methodist University-David J. Meltzer, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. Archived from the original on 2009-11-01.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Jorney of mankind". Brad Shaw Foundation.

- ↑ Lister, Adrian; Bahn, Paul G (2007-11-10). Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age. By Adrian Lister, Paul G. Bahn. ISBN 978-0-7112-2801-6.

- ↑ Jordan, David K (2009). "Prehistoric Beringia". University of California-San Diego. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ↑ Jody Hey, "On the Number of New World Founders: A Population Genetic Portrait of the Peopling of the Americas", Public Library of Science Biology, 3(6):e193 (2005)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 "Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders". PLoS ONE (eISSN-1932-6203). PMC 1952074.

- ↑ Than, Ker (2008). "New World Settlers Took 20,000-Year Pit Stop". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American.

- ↑ "First Americans Endured 20,000-Year Layover - Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News". Retrieved 2009-10-05.

- ↑ (2003) "Y-Chromosome Evidence for Differing Ancient Demographic Histories in the Americas," (pdf) Maria-Catira Bortolini, Francisco M. Salzano, Mark G. Thomas, Steven Stuart, Selja P. K. Nasanen, Claiton H. D. Bau, Mara H. Hutz, Zulay Layrisse, Maria L. Petzl-Erler, Luiza T. Tsuneto, Kim Hill, Ana M. Hurtado, Dinorah Castro-de-Guerra, Maria M. Torres, Helena Groot, Roman Michalski, Pagbajabyn Nymadawa, Gabriel Bedoya, Neil Bradman, Damian Labuda, Andres Ruiz-Linares. Department of Biology, University College, London; Departamento de Genética, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil; Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Caracas, Venezuela; Departamento de Genética, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil; 5Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; 6Laboratorio de Genética Humana, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá; Victoria Hospital, Prince Albert, Canada; Subassembly of Medical Sciences, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia; Laboratorio de Genética Molecular, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia; Université de Montréal, Montreal. 73:524-539. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ↑ Dyke, A.S., A. Moore, and L. Robertson, 2003, Deglaciation of North America, Geological Survey of Canada Open File, 1574. (Thirty-two digital maps at 1:7,000,000 scale with accompanying digital chronological database and one poster (two sheets) with full map series.)

- ↑ "First Americans Endured 20,000-Year Layover - Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News". Retrieved 2009-11-18.

Archaeological evidence, in fact, recognizes that people started to leave Beringia for the New World around 40,000 years ago, but rapid expansion into North America didn't occur until about 15,000 years ago, when the ice had literally broken

page 2 - ↑ Bronowski, Jacob (1975). The Ascent of Man. British Broadcasting Corporation. pp. 92–94. ISBN 0-563-10498-8.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Adachi N, Shinoda K, Umetsu K, et al.(2009). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Jomon skeletons from the Funadomari site, Hokkaido, and its implication for the origins of Native American". Am J Phys Anthropol 2009 Mar; 138(3) :255-65.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Brian M. Kemp, Ripan S. Malhi, John McDonough, Deborah A. Bolnick,Jason A. Eshleman, Olga Rickards, Cristina Martinez-Labarga, John R. Johnson, Joseph G. Lorenz, E. James Dixon, Terence E. Fifield, Timothy H. Heaton, Rosita Worl, and David Glenn Smith(2007). "Genetic Analysis of Early Holocene Skeletal Remains From Alaska and its Implications for the Settlement of the Americas" (PDF). Am J Phys Anthropol 2009 Mar; 138(3) :255-65.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Learn about Y-DNA Haplogroup Q. Genebase Tutorials" (VERBAL TUTORIAL POSSIBLE). Genebase Systems. 2008. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Orgel L (2004). "Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of the RNA world" (PDF). Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 39 (2): 99–123. doi:10.1080/10409230490460765. PMID 15217990. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ↑ Derenko M, Malyarchuk B, Grzybowski T, Denisova G, Rogalla U, et al. (2010). "Origin and Post-Glacial Dispersal of Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups C and D in Northern Asia.". PLoS ONE 5(12): e15214. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015214.

- ↑ Ugo A. Perego1, Alessandro Achilli1, Norman Angerhofer, Matteo Accetturo, Maria Pala, Anna Olivieri, Baharak Hooshiar Kashani, Kathleen H. Ritchie, Rosaria Scozzari, Qing-Peng Kong, Natalie M. Myres, Antonio Salas, Ornella Semino, Hans-Jürgen Bandelt, Scott R. Woodward, and Antonio Torroni1,. "Distinctive Paleo-Indian Migration Routes from Beringia Marked by Two Rare mtDNA Haplogroups". Current Biology, Volume 19, Issue 1, 13 January 2009, Pages 1–8, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.058.

- ↑ "Summary of knowledge on the subclades of Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ↑ Ruhlen M (November 1998). "The origin of the Na-Dene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (23): 13994–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13994. PMC 25007. PMID 9811914.

- ↑ Zegura SL, Karafet TM, Zhivotovsky LA, Hammer MF; Karafet; Zhivotovsky; Hammer (January 2004). "High-resolution SNPs and microsatellite haplotypes point to a single, recent entry of Native American Y chromosomes into the Americas". Molecular Biology and Evolution 21 (1): 164–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh009. PMID 14595095.

- ↑ Saillard, Juliette Saillard, Peter Forster, Niels Lynnerup1, Hans-Jürgen Bandelt and Søren Nørby; Forster, Peter; Lynnerup, Niels; Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen; Nørby, Søren (2000). "mtDNA Variation among Greenland Eskimos. The Edge of the Beringian Expansion". Laboratory of Biological Anthropology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research,University of Cambridge, Cambridge, University of Hamburg, Hamburg 67 (3): 718. doi:10.1086/303038. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ↑ Schurr, Theodore G. (2004). "The peopling of the New World - Perspectives from Molecular Anthropology". Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania (Annual Review of Anthropology) 33: Vol. 33, 551–583. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143932. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ↑ "Native American Mitochondrial DNA Analysis Indicates That the Amerind and the Nadene Populations Were Founded by Two Independent Migrations". Center for Genetics and Molecular Medicine and Departments of Biochemistry and Anthropology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Genetics Society of America. Vol 130, 153-162. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Charles C. Mann (2006), 1491: new revelations of the Americas before Columbus, Random House Digital, p. 143, ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 Madsen, David B., Entering America: Northeast Asia and Beringia Before the Last Glacial Maximum, University of Utah Press, 2004

- ↑ Goebel, Ted, and Buvit, Ian., From the Yensei to the Yukon: Interpreting Lithic Assemblages in Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene Beringia, Center for the Study of the First Americans, 2011

- ↑ Gibbon, Guy E; Ames, Kenneth M (1998). Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia|work=. By Guy E. Gibbon, Kenneth M. Ames (1998)|isbn=. ISBN 978-0-8153-0725-9.

- ↑ "Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders", ". PLoS ONE (eISSN-1932-6203). PMC 1952074. 2 (9), 2007, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000829, PMID 17786201

- ↑ thumb 250px right, "A Three-Stage Colonization Model for the Peopling of the Americas, PLoS ONE 3(2): e1596. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001596, published February 13, 2008."

- ↑ "Epic explorer crosses frozen sea". BBC News. 2006-04-03.

- ↑ Booth et al(2003), The Cordilleran Ice Sheet, Developments in Quaternary Science, vol.1 pp 17-43, ISSN 1571-0866 (PDF)

- ↑ Dyke, A S; Moore, A; Robertson, L., Deglaciation of North America, Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 1574, 2003

- ↑ Dyke, A S; Moore, A; Robertson, L., Deglaciation of North America, Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 1574, 2003

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 http://www.geotimes.org/feb04/feature_Quest.html

- ↑ Erlandson, Jon M., and Braje, Todd J., 2011, From Asia to the Americas by boat? Paleogeography, paleoecology, and stemmed points of the northwest Pacific, Quaternary International 239 (2011), p.28-37 (PDF)

- ↑ Erlandson, Jon M., and Braje, Todd J., 2011, From Asia to the Americas by boat? Paleogeography, paleoecology, and stemmed points of the northwest Pacific, Quaternary International 239 (2011), p.28-37

- ↑ Raff, J. A.; Bolnick, D. A. (2014-02-13). "Palaeogenomics: Genetic roots of the first Americans". Nature 506 (7487): 162–163. doi:10.1038/506162a.

- ↑ Callaway, E. (2014-02-12). "Ancient genome stirs ethics debate". Nature 506 (7487): 142–143. doi:10.1038/506142a.

- ↑ Watson, T. (2014-02-13). "New theories shine light on origins of Native Americans". USA Today web site. Gannett Company. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Rasmussen, M.; Anzick, S. L.; Waters, M. R.; Skoglund, P.; DeGiorgio, M.; Stafford, T. W.; Rasmussen, S.; Moltke, I.; Albrechtsen, A.; Doyle, S. M.; Poznik, G. D.; Gudmundsdottir, V.; Yadav, R.; Malaspinas, A. S.; White, S. S.; Allentoft, M. E.; Cornejo, O. E.; Tambets, K.; Eriksson, A.; Heintzman, P. D.; Karmin, M.; Korneliussen, T. S.; Meltzer, D. J.; Pierre, T. L.; Stenderup, J.; Saag, L.; Warmuth, V. M.; Lopes, M. C.; Malhi, R. S.; Brunak, S. R.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Barnes, I.; Collins, M.; Orlando, L.; Balloux, F.; Manica, A.; Gupta, R.; Metspalu, M.; Bustamante, C. D.; Jakobsson, M.; Nielsen, R.; Willerslev, E. (2014-02-13). "The genome of a Late Pleistocene human from a Clovis burial site in western Montana". Nature 506 (7487): 225–229. doi:10.1038/nature13025. PMID 24522598.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared M. (1991). The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee. Radius. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-09-174268-3. OCLC 21594215.

- ↑ Dillehay, Thomas (2000). The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-07669-6.

- ↑ "Faeces hint at first Americans". BBC. April 3, 2008. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ↑ Jenkins / Willerslev et al. "Clovis Age Western Stemmed Projectile Points and Human Coprolites at the Paisley Caves" Science (Magazine), 13 July 2012. Retrieved: 13 July 2012.

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble. "Spearheads and DNA Point to a Second Founding Society in North America" New York Times, 12 July 2012. Retrieved: 13 July 2012.

- ↑ Thomas H. Maugh II. "Who lived here first? New info on North America's earliest residents" Los Angeles Times, 12 July 2012. Retrieved: 13 July 2012.

- ↑ Joseph F. Powell (November 14, 2005), The first Americans: race, evolution, and the origin of Native Americans, Cambridge University Press, p. 123, ISBN 978-0-521-82350-0

- ↑ Bruce Bradley; Dennis Stanford (2004). "The North Atlantic ice-edge corridor: a possible Palaeolithic route to the New World" (PDF). World Archaeology 36 (4): 459–478. doi:10.1080/0043824042000303656.

- ↑ Carey, Bjorn (2006-02-19). "First Americans may have been European". Life Science.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ↑ Lawrence Guy Straus; David J. Meltzer; Ted Goebel, Ice Age Atlantis? Exploring the Solutrean-Clovis ‘connection’ (PDF), retrieved 2011-04-24,

Bradley and Stanford (2004) have raised now, in several instances, the claim that European Upper Paleolithic Solutrean peoples colonized North America, and gave rise to the archaeological complex known as Clovis. They do so in the face of some obvious challenges—notably the several thousand miles of ocean and the 5000 radiocarbon years that separate the two. And yet they argue in their recent paper that the archaeological evidence in support of a historical connection is ‘overwhelming’. We are profoundly skeptical of this claim; we believe that the many differences between Solutrean and Clovis are far more significant than the few similarities, the latter being readily explained by the well-known phenomenon of technological convergence or parallelism. The origin and arrival time of the first Americans remain uncertain, but not so uncertain that we need to look elsewhere other than north-east Asia.

- ↑ Carl Waldman (2009). ATLAS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN (3 ed.). Facts on File, Inc. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8160-6858-6.

- ↑ Nelson J.R. Fagundes; Ricardo Kanitz; Roberta Eckert; Ana C.S. Valls; Mauricio R. Bogo; Francisco M. Salzano; David Glenn Smith; Wilson A. Silva Jr.; Marco A. Zago; Andrea K. Ribeiro-dos-Santos; Sidney E.B. Santos; Maria Luiza Petzl-Erler; Bonatto, S. L. (2008-03-03), "Mitochondrial Population Genomics Supports a Single Pre-Clovis Origin with a Coastal Route for the Peopling of the Americas", American Journal of Human Genetics (Elsevier) 82 (3): 583–92, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.013, PMC 2427228, PMID 18313026, retrieved 2011-04-24,

Our results strongly support the hypothesis that haplogroup X, together with the other four main mtDNA haplogroups, was part of the gene pool of a single Native American founding population; therefore they do not support models that propose haplogroup-independent migrations, such as the migration from Europe posed by the Solutrean hypothesis.

- ↑ Gornitz, Vivian (January 2007). "Sea Level Rise, After the Ice Melted and Today". Goddard Institute for Space Studies. NASA. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "California islands give up evidence of early seafaring: Numerous artifacts found at late Pleistocene sites on the Channel Islands," ScienceDaily, March 4, 2011. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/03/110303141540.htm

- ↑ Joseph F. Powell (November 14, 2005), The first Americans: race, evolution, and the origin of Native Americans, Cambridge University Press, p. 123, ISBN 978-0-521-82350-0

- ↑ Bruce Bradley; Dennis Stanford (2004). "The North Atlantic ice-edge corridor: a possible Palaeolithic route to the New World" (PDF). World Archaeology 36 (4): 459–478. doi:10.1080/0043824042000303656.

- ↑ Carey, Bjorn (2006-02-19). "First Americans may have been European". Life Science.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ↑ Lawrence Guy Straus; David J. Meltzer; Ted Goebel, Ice Age Atlantis? Exploring the Solutrean-Clovis ‘connection’ (PDF), retrieved 2011-04-24,

Bradley and Stanford (2004) have raised now, in several instances, the claim that European Upper Paleolithic Solutrean peoples colonized North America, and gave rise to the archaeological complex known as Clovis. They do so in the face of some obvious challenges—notably the several thousand miles of ocean and the 5000 radiocarbon years that separate the two. And yet they argue in their recent paper that the archaeological evidence in support of a historical connection is ‘overwhelming’. We are profoundly skeptical of this claim; we believe that the many di?erences between Solutrean and Clovis are far more significant than the few similarities, the latter being readily explained by the well-known phenomenon of technological convergence or parallelism. The origin and arrival time of the ?rst Americans remain uncertain, but not so uncertain that we need to look elsewhere other than north-east Asia.

- ↑ Carl Waldman (2009). ATLAS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN (3 ed.). Facts on File, Inc. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8160-6858-6.

- ↑ Nelson J.R. Fagundes; Ricardo Kanitz; Roberta Eckert; Ana C.S. Valls; Mauricio R. Bogo; Francisco M. Salzano; David Glenn Smith; Wilson A. Silva Jr.; Marco A. Zago; Andrea K. Ribeiro-dos-Santos; Sidney E.B. Santos; Maria Luiza Petzl-Erler; Bonatto, S. L. (2008-03-03), "Mitochondrial Population Genomics Supports a Single Pre-Clovis Origin with a Coastal Route for the Peopling of the Americas", American Journal of Human Genetics (Elsevier) 82 (3): 583–92, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.013, PMC 2427228, PMID 18313026, retrieved 2011-04-24,

Our results strongly support the hypothesis that haplogroup X, together with the other four main mtDNA haplogroups, was part of the gene pool of a single Native American founding population; therefore they do not support models that propose haplogroup-independent migrations, such as the migration from Europe posed by the Solutrean hypothesis.

- ↑ Alice Beck Kehoe (2003)The Fringe of American Archaeology: Transoceanic and Transcontinental Contacts in Prehistoric America. Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee - Journal of Scientific? Exploration, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 19–36. 0892-3310/03

- ↑ Garrett G. Fagan (2006). Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public. Psychology Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-415-30592-1.

Bibliography

- Jared Diamond, Guns, germs and steel. A short history of everybody for the last 13,000 years, 1997.

- Dixon, E. James. Quest for the Origins of the First Americans. University of New Mexico Press. 1993.

- Dixon, E. James. Bones, Boats, and Bison: the Early Archeology of Western North America. University of New Mexico Press. 1993.

- Erlandson, Jon M. Early Hunter-Gatherers of the California Coast. Plenum Press. 1994.

- Erlandson, Jon M. The Archaeology of Aquatic Adaptations: Paradigms for a New Millennium. Journal of Archaeological Research, Vo. 9, 2001. pp. 287–350.

- Erlandson, Jon M. Anatomically Modern Humans, Maritime Migrations, and the Peopling of the New World. In The First Americans: The Pleistocene Colonization of the New World, edited by N. Jablonski, 2002. pp. 59–92. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. San Francisco.

- Erlandson, Jon. M., M. H. Graham, Bruce J. Bourque, Debra Corbett, James A. Estes, & R. S. Steneck. The Kelp Highway Hypothesis: Marine Ecology, The Coastal Migration Theory, and the Peopling of the Americas. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, Vo. 2, 2007. pp. 161–174.

- Jason A. Eshleman, Ripan S. Malhi, and David Glenn Smith, "Mitochondrial DNA Studies of Native Americans: Conceptions and Misconceptions of the Population Prehistory of the Americas", Evolutionary Anthropology, 12:7–18 (2003)

- Fedje, & Christensen. Modeling Paleoshorelines and Locating Early Holocene Coastal Sites in Haida Gwaii. American Antiquity, Vol. 64, #4, 1999. pp. 635–652.

- E. F. Greenman, "The Upper Palaeolithic and the New World", Current Anthropology, 4: 41–66 (1963)

- Jody Hey, "On the Number of New World Founders: A Population Genetic Portrait of the Peopling of the Americas", Public Library of Science Biology, 3(6):e193 (2005).

- Jones, Peter N. Respect for the Ancestors: American Indian Cultural Affiliation in the American West. Bauu Institute Press. 2005.

- Matson and Coupland. The Prehistory of the Northwest Coast. Academic Press. New York. 1995.

- Adovasio, J. M., with Jake Page. The First Americans: In Pursuit of Archaeology's Greatest Mystery. New York: Random House, 2002.

- Bradley, B.; Stanford, D. (2004). "The North Atlantic ice-edge corridor: a possible Palaeolithic route to the New World". World Archaeology 36 (4): 2004. doi:10.1080/0043824042000303656.

- Bradley, B.; Stanford, D. "The Solutrean-Clovisct=result connection: reply to Straus, Meltzer and Goebel". World Archaeology 38. JSTOR 40024066.

- Lauber, Patricia. Who Came First? New Clues to Prehistoric Americans. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2003.

- Snow, Dean R. "The First Americans and the Differentiation of Hunter-Gatherer Cultures." In Bruce G. Trigger and Wilcomb *E. Washburn, eds., The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Volume I: North America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 125-199.

- Jones, Peter N. "Respect for the Ancestors: American Indian Cultural Affiliation in the American West." Boulder, Colorado: Bauu Press. 2004

- Dixon, E. James. Bones, Boats and Bison: the Early Archeology of Western North America. University of New Mexico Press. 1999.

- Evidence Supports Earlier Date for People in North America, April 4, 2008

- Dennis J. Stanford, Bruce Bradely, Pre-Clovis First Americans: The Origin of America's Clovis Culture (University of California Press, 2012). ISBN 978-0-520-22783-5

- Dennis J. Stanford, Bruce A. Bradley, Across Atlantic Ice: The Origin of America's Clovis Culture (University of California Press (2012). ISBN 978-0-520-22783-5

- First peoples in a new world: colonizing ice age America - by David J Meltzer - University of California, Berkeley, 2009 ISBN 0-520-25052-4

- The First Americans: The Pleistocene Colonization of the New World - by Nina G. Jablonski - California Academy of Sciences, 2002 ISBN 0-940228-49-1

- Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey (book) - by Spencer Wells - Princeton University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-8129-7146-9

See also

- Early human migrations

- Origins of Paleoindians

- Dené–Yeniseian languages, a proposed family of languages that are spoken by indigenous peoples of Asia and North America

- Historical migration

- Bluefish Caves

- History of Mesoamerica (Paleo-Indian)

- Paleo-Indians period (Canada)

- Norse colonization of the Americas

- Olmec alternative origin speculations

- Recent African origin of modern humans

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

- List of countries and islands by first human settlement

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indigenous nations of the Americas. |

- "When Did Humans Come to the Americas?" - Smithsonian Magazine February 2013

- Ordering information and news items for The Dene–Yeniseian Connection; the 2011 2nd printing has corriagenda for 14 articles in the 2010 ist printing

- Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey (movie) on YouTube - by Spencer Wells - PBS and National Geographic Channel, 2003 - 120 Minutes, UPC/EAN: 841887001267

- Atlas of the Human Journey, Genographic Project, National Geographic

- An mtDNA view of the peopling of the world by Homo sapiens Cambridge DNA's

- Journey of Mankind - Genetic Map – Bradshaw Foundation

- The Paleoindian Period – United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service

- Alabama Archaeology: Prehistoric Alabama – The University of Alabama, Department of Archaeology

- The Paleoindian Database – The University of Tennessee, Department of Anthropology.

- Paleoindians and the Great Pleistocene Die-Off – American Academy of Arts and Sciences, National Humanities Center

.svg.png)