Separable state

In quantum mechanics, separable quantum states are states without quantum entanglement.

Separable pure states

For simplicity, the following assumes all relevant state spaces are finite-dimensional. First, consider separability for pure states.

Let  and

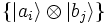

and  be quantum mechanical state spaces, that is, finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces with basis states

be quantum mechanical state spaces, that is, finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces with basis states  and

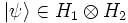

and  , respectively. By a postulate of quantum mechanics, the state space of the composite system is given by the tensor product

, respectively. By a postulate of quantum mechanics, the state space of the composite system is given by the tensor product

with base states  , or in more compact notation

, or in more compact notation  . From the very definition of the tensor product, any vector of norm 1, i.e. a pure state of the composite system, can be written as

. From the very definition of the tensor product, any vector of norm 1, i.e. a pure state of the composite system, can be written as

If a pure state  can be written in the form

can be written in the form  where

where  is a pure state of the i-th subsystem, it is said to be separable. Otherwise it is called entangled. When a system is in an entangled pure state, it is not possible to assign states to its subsystems. This will be true, in the appropriate sense, for the mixed state case as well.

is a pure state of the i-th subsystem, it is said to be separable. Otherwise it is called entangled. When a system is in an entangled pure state, it is not possible to assign states to its subsystems. This will be true, in the appropriate sense, for the mixed state case as well.

Formally, the embedding of a product of states into the product space is given by the Segre embedding. That is, a quantum-mechanical pure state is separable if and only if it is in the image of the Segre embedding.

The above discussion can be extended to the case of when the state space is infinite-dimensional with virtually nothing changed.

Separability for mixed states

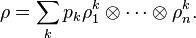

Consider the mixed state case. A mixed state of the composite system is described by a density matrix  acting on

acting on  . ρ is separable if there exist

. ρ is separable if there exist  ,

,  and

and  which are mixed states of the respective subsystems such that

which are mixed states of the respective subsystems such that

where

Otherwise  is called an entangled state. We can assume without loss of generality in the above expression that

is called an entangled state. We can assume without loss of generality in the above expression that  and

and  are all rank-1 projections, that is, they represent pure ensembles of the appropriate subsystems. It is clear from the definition that the family of separable states is a convex set.

are all rank-1 projections, that is, they represent pure ensembles of the appropriate subsystems. It is clear from the definition that the family of separable states is a convex set.

Notice that, again from the definition of the tensor product, any density matrix, indeed any matrix acting on the composite state space, can be trivially written in the desired form, if we drop the requirement that  and

and  are themselves states and

are themselves states and  If these requirements are satisfied, then we can interpret the total state as a probability distribution over uncorrelated product states.

If these requirements are satisfied, then we can interpret the total state as a probability distribution over uncorrelated product states.

In terms of quantum channels, a separable state can be created from any other state using local actions and classical communication while an entangled state cannot.

When the state spaces are infinite-dimensional, density matrices are replaced by positive trace class operators with trace 1, and a state is separable if it can be approximated, in trace norm, by states of the above form.

If there is only a single non-zero  , then the state is called simply separable (or it is called a "product state").

, then the state is called simply separable (or it is called a "product state").

Extending to the multipartite case

The above discussion generalizes easily to the case of a quantum system consisting of more than two subsystems. Let a system have n subsystems and have state space  . A pure state

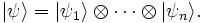

. A pure state  is separable if it takes the form

is separable if it takes the form

Similarly, a mixed state ρ acting on H is separable if it is a convex sum

Or, in the infinite-dimensional case, ρ is separable if it can be approximated in the trace norm by states of the above form.

Separability criterion

The problem of deciding whether a state is separable in general is sometimes called the separability problem in quantum information theory. It is considered to be a difficult problem. It has been shown to be NP-hard.[1][2] Some appreciation for this difficulty can be obtained if one attempts to solve the problem by employing the direct brute force approach, for a fixed dimension. We see that the problem quickly becomes intractable, even for low dimensions. Thus more sophisticated formulations are required. The separability problem is a subject of current research.

A separability criterion is a necessary condition a state must satisfy to be separable. In the low-dimensional (2 X 2 and 2 X 3) cases, the Peres-Horodecki criterion is actually a necessary and sufficient condition for separability. Other separability criteria include the range criterion and reduction criterion. See Ref.[3] for a review of separability criteria in discrete variable systems.

In continuous variable systems, the Peres-Horodecki criterion also applies. Specifically, Simon [4] formulated a particular version of the Peres-Horodecki criterion in terms of the second-order moments of canonical operators and showed that it is necessary and sufficient for  -mode Gaussian states (see Ref.[5] for a seemingly different but essentially equivalent approach). It was later found [6] that Simon's condition is also necessary and sufficient for

-mode Gaussian states (see Ref.[5] for a seemingly different but essentially equivalent approach). It was later found [6] that Simon's condition is also necessary and sufficient for  -mode Gaussian states, but no longer sufficient for

-mode Gaussian states, but no longer sufficient for  -mode Gaussian states. Simon's condition can be generalized by taking into account the higher order moments of canonical operators [7] or by using entropic measures.[8]

-mode Gaussian states. Simon's condition can be generalized by taking into account the higher order moments of canonical operators [7] or by using entropic measures.[8]

Characterization via algebraic geometry

Quantum mechanics may be modelled on a projective Hilbert space, and the categorical product of two such spaces is the Segre embedding. In the bipartite case, a quantum state is separable if and only if it lies in the image of the Segre embedding. Jon Magne Leinaas, Jan Myrheim and Eirik Ovrum in their paper "Geometrical aspects of entanglement"[9] describe the problem and study the geometry of the separable states as a subset of the general state matrices. This subset have some intersection with the subset of states holding Peres-Horodecki criterion. In this paper, Leinaas et al. also give a numerical approach to test for separability in the general case.

Testing for separability

Since separability testing in a general case is an NP-hard.[1][2] problem, in their paper,[9] Leinaas et al. offer a numerical approach, iteratively refining an estimated separable state towards the target state to be tested, checking if the target state can indeed be reached. An implementation of the algorithm (including a built in Peres-Horodecki criterion testing) is brought in the "StateSeparator" web-app

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gurvits, L., Classical deterministic complexity of Edmonds’ problem and quantum entanglement, in Proceedings of the 35th ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, ACM Press, New York, 2003.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sevag Gharibian, Strong NP-Hardness of the Quantum Separability Problem, Quantum Information and Computation, Vol. 10, No. 3&4, pp. 343-360, 2010. arXiv:0810.4507.

- ↑ Gühne, Otfried; Tóth, Géza. "Entanglement detection". Physics Reports 474 (1-6): 1–75. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2009.02.004.

- ↑ Simon, R. "Peres-Horodecki Separability Criterion for Continuous Variable Systems". Physical Review Letters 84 (12): 2726–2729. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.2726.

- ↑ Duan, Lu-Ming; Giedke, G.; Cirac, J. I.; Zoller, P. "Inseparability Criterion for Continuous Variable Systems". Physical Review Letters 84 (12): 2722–2725. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.2722.

- ↑ Werner, R. F.; Wolf, M. M. "Bound Entangled Gaussian States". Physical Review Letters 86 (16): 3658–3661. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3658.

- ↑ Shchukin, E.; Vogel, W. "Inseparability Criteria for Continuous Bipartite Quantum States". Physical Review Letters 95 (23). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.230502. Hillery, Mark; Zubairy, M.Suhail. "Entanglement Conditions for Two-Mode States". Physical Review Letters 96 (5). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.050503.

- ↑ Walborn, S.; Taketani, B.; Salles, A.; Toscano, F.; de Matos Filho, R. "Entropic Entanglement Criteria for Continuous Variables". Physical Review Letters 103 (16). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.160505. Huang, Yichen. "Entanglement Detection: Complexity and Shannon Entropic Criteria". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 59 (10): 6774–6778. doi:10.1109/TIT.2013.2257936.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Geometrical aspects of entanglement", Physical Review A 74, 012313 (2006)