Self-information

In information theory, self-information is a measure of the information content associated with an event in a probability space or with the value of a discrete random variable. It is expressed in a unit of information, for example bits, nats, or hartleys, depending on the base of the logarithm used in its calculation.

The term self-information is also sometimes used as a synonym of the related information-theoretic concept of entropy. These two meanings are not equivalent, and this article covers the first sense only.

Definition

By definition, the amount of self-information contained in a probabilistic event depends only on the probability of that event: the smaller its probability, the larger the self-information associated with receiving the information that the event indeed occurred.

Further, by definition, the measure of self-information is positive and additive. If an event C is the intersection of two independent events A and B, then the amount of information at the proclamation that C has happened, equals the sum of the amounts of information at proclamations of event A and event B respectively: I(A ∩ B)=I(A)+I(B).

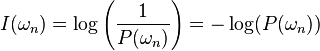

Taking into account these properties, the self-information  associated with outcome

associated with outcome  with probability

with probability  is:

is:

This definition complies with the above conditions. In the above definition, the base of the logarithm is not specified: if using base 2, the unit of  is bits. When using the logarithm of base

is bits. When using the logarithm of base  , the unit will be the nat. For the log of base 10, the unit will be hartley.

, the unit will be the nat. For the log of base 10, the unit will be hartley.

As a quick illustration, the information content associated with an outcome of 4 heads (or any specific outcome) in 4 consecutive tosses of a coin would be 4 bits (probability 1/16), and the information content associated with getting a result other than the one specified would be 0.09 bits (probability 15/16). See below for detailed examples.

This measure has also been called surprisal, as it represents the "surprise" of seeing the outcome (a highly improbable outcome is very surprising). This term was coined by Myron Tribus in his 1961 book Thermostatics and Thermodynamics.

The information entropy of a random event is the expected value of its self-information.

Self-information is an example of a proper scoring rule.

Examples

- On tossing a coin, the chance of 'tail' is 0.5. When it is proclaimed that indeed 'tail' occurred, this amounts to

- I('tail') = log2 (1/0.5) = log2 2 = 1 bits of information.

- When throwing a fair dice, the probability of 'four' is 1/6. When it is proclaimed that 'four' has been thrown, the amount of self-information is

- I('four') = log2 (1/(1/6)) = log2 (6) = 2.585 bits.

- When, independently, two dice are thrown, the amount of information associated with {throw 1 = 'two' & throw 2 = 'four'} equals

- I('throw 1 is two & throw 2 is four') = log2 (1/P(throw 1 = 'two' & throw 2 = 'four')) = log2 (1/(1/36)) = log2 (36) = 5.170 bits.

This outcome equals the sum of the individual amounts of self-information associated with {throw 1 = 'two'} and {throw 2 = 'four'}; namely 2.585 + 2.585 = 5.170 bits.

- In the same two dice situation we can also consider the information present in the statement "The sum of the two dice is five"

- I('The sum of throws 1 and 2 is five') = log2 (1/P('throw 1 and 2 sum to five')) = log2 (1/(4/36)) = 3.17 bits. The (4/36) is because there are four ways out of 36 possible to sum two dice to 5. This shows how more complex or ambiguous events can still carry information.

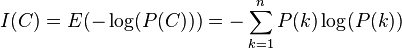

Self-information of a partitioning

The self-information of a partitioning of elements within a set (or clustering) is the expectation of the information of a test object; if we select an element at random and observe in which partition/cluster it exists, what quantity of information do we expect to obtain? The information of a partitioning  with

with  denoting the fraction of elements within partition

denoting the fraction of elements within partition  is [1]

is [1]

Relationship to entropy

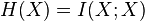

The entropy is the expected value of the self-information of the values of a discrete random variable. Sometimes, the entropy itself is called the "self-information" of the random variable, possibly because the entropy satisfies  , where

, where  is the mutual information of X with itself.[2]

is the mutual information of X with itself.[2]

References

- ↑ Marina Meilă; Comparing clusterings—an information based distance; Journal of Multivariate Analysis, Volume 98, Issue 5, May 2007

- ↑ Thomas M. Cover, Joy A. Thomas; Elements of Information Theory; p. 20; 1991.

- C.E. Shannon, A Mathematical Theory of Communication, Bell Syst. Techn. J., Vol. 27, pp 379–423, (Part I), 1948.