Selenomethionine

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

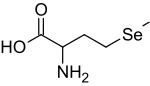

| IUPAC name

2-Amino-4-methylselanyl-butanoic acid | |||

| Other names

MSE | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 3211-76-5 (L) 1464-42-2 (D/L) | |||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:27585 | ||

| ChemSpider | 14375 | ||

| |||

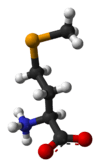

| Jmol-3D images | Image | ||

| PubChem | 15103 | ||

| |||

| UNII | 964MRK2PEL | ||

| Properties | |||

| C5H11NO2Se | |||

| Molar mass | 196.106 g/mol | ||

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Selenomethionine is a naturally occurring amino acid containing selenium. The L-enantiomer of selenomethionine, known as L-selenomethionine, is a common natural food source of selenium and is the predominant form of selenium found in Brazil nuts, cereal grains, soybeans, and grassland legumes, while Se-methylselenocysteine, or its γ-glutamyl derivative, is the major form of selenium found in Astragalus, Allium, and Brassica species.[1] In vivo, selenomethionine is randomly incorporated instead of methionine. Selenomethionine is readily oxidized.[2] Its antioxidant activity arises from its ability to deplete reactive oxygen species. Selenium and sulfur are chalcogens that share many chemical properties so the substitution of methionine with selenomethionine may have only a limited effect on protein structure and function. However, the incorporation of selenomethionine into tissue proteins and keratin in horses causes alkali disease. Alkali disease is characterized by emaciation, loss of hair, deformation and shedding of hooves, loss of vitality, and erosion of the joints of long bones.

Incorporation of selenomethionine into proteins in place of methionine aids the structure elucidation of proteins by X-ray crystallography using single- or multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD or MAD).[3] The incorporation of heavy atoms such as selenium helps solve the phase problem in X-ray crystallography.[4]

It has been suggested that selenomethionine, which is an organic form of selenium, is easier for the human body to absorb than selenite, which is an inorganic form.[5] It was determined in a clinical trial that selenomethionine is absorbed 19% better than selenite.[5]

See also

- Selenocysteine, another selenium-containing amino acid, but one that is incorporated into specific locations of specific proteins as directed by the genetic code.

- Selenoprotein

- Canadian Reference Material of selenomethionine

References

- ↑ P. D. Whanger, Selenocompounds in plants and animals and their biological significance, Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 21(3), 223–232 (2002).

- ↑ E. Block, M. Birringer, W. Jiang, T. Nakahodo, H.J. Thompson, P.J. Toscano, H. Uzar, X. Zhang, and Z. Zhu, Allium chemistry: synthesis, natural occurrence, biological activity, and chemistry of Se-alk(en)ylselenocysteines and their γ-glutamyl derivatives and oxidation products, J. Agric. Food Chem., 49, 458-470 (2001).

- ↑ W. A. Hendrickson, Maturation of MAD phasing for the determination of macromolecular structures, Journal of Synchrotron Radiation, 6(4), 845-851 (1999).

- ↑ A. M. Larsson, Preparation and crystallization of selenomethionine protein, IUL Biotechnology Series, 8 (Protein Crystallization), 135-154 (2009).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Product Review: Supplements for Cancer Prevention (Green Tea, Lycopene, and Selenium)". ConsumerLab.com. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

Selenium supplements are available in organic and inorganic forms. Some research suggests that the inorganic form, selenite, is harder for the body to absorb than organic forms such as selenomethionine (selenium bound to methionine, an essential amino acid) or high-selenium yeast (which contains selenomethionine). A recent clinical trial found that selenomethionine had 19% better absorption than selenite; absorption from selenium yeast was about 10% better than selenite.