Seikan Tunnel

|

| |

| Map of the Seikan Tunnel. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Beneath the Tsugaru Strait |

| Coordinates | 41°18′57″N 140°20′06″E / 41.3157°N 140.3351°ECoordinates: 41°18′57″N 140°20′06″E / 41.3157°N 140.3351°E |

| Status | Active |

| Start | Honshu |

| End | Hokkaido |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 13 March 1988 |

| Owner | Japan Railway Construction, Transport and Technology Agency |

| Operator | JR Hokkaido |

| Technical | |

| Track length | 53.85 km (23.3 km undersea) |

| No. of tracks | double track rail tunnel |

| Track gauge | Mixed |

| Electrified | Yes |

| Operating speed | 140 km/h (85 mph) |

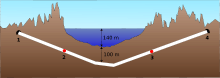

The Seikan Tunnel (青函トンネル Seikan Tonneru or 青函隧道 Seikan Zuidō) is a 53.85 km (33.46 mi) railway tunnel in Japan, with a 23.3 km (14.5 mi) long portion under the seabed. The track level is about 100 metres (330 ft) below the seabed and 240 m (790 ft) below sea level.[1] It travels beneath the Tsugaru Strait — connecting Aomori Prefecture on the main Japanese island of Honshu with the northern island of Hokkaido — as part of the Kaikyo Line of Hokkaido Railway Company (JR Hokkaido). The name Seikan comes from combining the on'yomi readings of the first characters of Aomori (青森), the nearest major city on the Honshu side of the strait, and Hakodate (函館), the nearest major city on the Hokkaido side.

Seikan is both the longest and the deepest operational main-line rail tunnel in the world (though Line 3 of the Guangzhou Metro’s central tunnel has been longer since 2010). The Gotthard Base Tunnel in Switzerland will be longer when it opens to traffic in 2016. Seikan is also the longest undersea tunnel in the world, but the Channel Tunnel between the United Kingdom and France has a longer undersea portion.[2]

History

Connecting the islands Honshu and Hokkaido by a fixed link had been considered since the Taishō period (1912–1925), but serious surveying commenced only in 1946, induced by the loss of overseas territory at the end of World War II and the need to accommodate returnees. In 1954, five ferries, including the Toya Maru, sank in the Tsugaru Strait during a typhoon, killing 1,430 passengers. The following year, Japanese National Railways (JNR) expedited the tunnel investigation.[3] Also of concern was the increasing traffic between the two islands. A booming economy saw traffic levels on the JNR-operated Seikan (a contraction of principal cities Aomori and Hakodate[4]) Ferry doubled to 4,040,000 persons/year from 1955 to 1965, and cargo levels rose 1.7 times to 6,240,000 tonnes/year. In 1971, traffic forecasts predicted increasing growth that would outstrip the ability of the ferry pier facility, which was constrained by geographical conditions.

In September 1971, the decision was made to commence work on the tunnel. A Shinkansen-capable cross section was selected, with plans to extend the Shinkansen network.[3] Arduous construction in difficult geological conditions proceeded. 34 workers were killed during construction.[5] On 27 January 1983, Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone pressed a switch that set off a blast that completed the pilot tunnel. Similarly on 10 March 1985, Minister of Transport Tokuo Yamashita symbolically holed through the main tunnel.[3]

The success of the project was questioned at the time, as the 1971 traffic predictions were overestimates. Instead of the traffic rate increasing as predicted to a peak in 1985, it peaked earlier in 1978 and then proceeded to decrease. The decrease was attributed to the slowdown in Japan's economy since the first oil crisis in 1973 and to advances made in air transport facilities and longer-range sea transport.[6]

The tunnel was opened on 13 March 1988, having cost a total of ¥538.4 billion (US$3.6 billion) to construct.[7] Once the tunnel was completed, all railway transport between Honshu and Hokkaido used it. However, for passenger transport, 90% of people use air due to the speed and cost. For example, to travel between Tokyo and Sapporo by train takes more than nine hours, with several transfers. By air, the journey is three hours and thirty minutes, including airport access times. Deregulation and competition in Japanese domestic air travel has brought down prices on the Tokyo-Sapporo route, making rail more expensive in comparison.[8]

The Hokutosei overnight train service, which began service after the completion of the Seikan Tunnel, is still popular among travelers. The newer and more luxurious Cassiopeia overnight train service is often fully booked.

Shinkansen trains will run through the tunnel once the first stage of the Hokkaido Shinkansen to Shin-Hakodate Station in Hakodate commences service in March 2016. The H5 Series Shinkansen trains used on this service will connect Tokyo and Hakodate in four hours ten minutes, at a maximum speed of 140 km/h (85 mph) within the tunnel and 320 km/h (200 mph) outside it.[9] The final stage is proposed to open to Sapporo Station in 2035 and is proposed to shorten the Tokyo-Sapporo rail journey to five hours. The Hokkaido Shinkansen will be operated by JR Hokkaido.

Construction timeline

- 24 April 1946: Geological surveying begins.[3]

- 26 September 1954: The train ferry Toya Maru sinks in the Tsugaru Strait.[3]

- 23 March 1964: Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation is established.[3]

- 28 September 1971: Construction on the main tunnel begins.[3]

- 27 January 1983: Pilot tunnel breakthrough.[3]

- 10 March 1985: Main tunnel breakthrough.[3]

- 13 March 1988: The tunnel opens.

Surveying, construction and geology

| Tsugaru Strait traffic data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Passengers (persons/yr) | Freight (t/yr) | Mode |

| 1955 | 2,020,000 | 3,700,000 | Seikan Ferry[3] |

| 1965 | 4,040,000 | 6,240,000 | Seikan Ferry[3] |

| 1970 | 9,360,000 | 8,470,000 | Seikan Ferry[3] |

| 1985 | 9,000,000[t 1] | 17,000,000 | 1971 Forecast[3] |

| 1988 | ~3,100,000 | — | Seikan Tunnel[8] |

| 1999 | ~1,700,000 | — | Seikan Tunnel[8] |

| 2001 | — | >5,000,000 | Seikan Tunnel[8] |

† | |||

Surveying started in 1946, and construction began in 1971. By August 1982, less than 700 metres of the tunnel remained to be excavated. First contact between the two sides was in 1983.[7] The Tsugaru Strait has eastern and western necks, both approximately 20 km (12 mi) across. Initial surveys undertaken in 1946 indicated that the eastern neck was up to 200 metres (656 feet) deep with volcanic geology. The western neck had a maximum depth of 140 metres (459 feet) and geology consisting mostly of sedimentary rocks of the Neogene period. The western neck was selected, with its conditions considered favourable for tunnelling.[10]

The geology of the undersea portion of the tunnel consists of volcanic rock, pyroclastic rock, and sedimentary rock of the Neogene Period.[4] The area is folded into a nearly vertical syncline, which means that the youngest rock is in the centre of the strait and encountered last. Divided roughly into thirds, the Honshū side consists of volcanic rocks (andesite, basalt etc.); the Hokkaido side consists of sedimentary rocks (Tertiary period tuff, mudstone, etc.); and the centre portion consists of Kuromatsunai strata (Tertiary period sand-like mudstone).[11] Igneous intrusions and faults caused crushing of the rock and complicated the tunnelling procedures.[10]

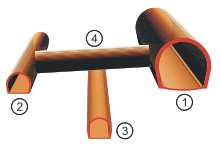

Initial geological investigation occurred from 1946 to 1963, which involved drilling the sea-bed, sonic surveys, submarine boring, observations using a mini-submarine, and seismic and magnetic surveys. To establish a greater understanding, a horizontal pilot boring was undertaken along the line of the service and main tunnels.[10] Tunnelling occurred simultaneously from the northern end and the southern. The dry land portions were tackled with traditional mountain tunnelling techniques, with a single main tunnel.[10] However, for the 23.3-kilometre undersea portion, three bores were excavated with increasing diameters respectively: an initial pilot tunnel, a service tunnel, and finally the main tunnel. The service tunnel was periodically connected to the main tunnel with a series of connecting shafts, at 600- to 1,000-metre intervals.[11] The pilot tunnel serves as the service tunnel for the central five-kilometre portion.[10] Beneath the Tsugaru Strait, the use of a tunnel boring machine (TBM) was abandoned after less than two kilometres (1.2 miles) owing to the variable nature of the rock and difficulty in accessing the face for advanced grouting.[4][10] Blasting with dynamite and mechanical picking were then used to excavate.

Maintenance

A 2002 report by Michitsugu Ikuma described, for the undersea section, that "the tunnel structure appears to remain in a good condition."[12] The amount of inflow has been decreasing with time, although it "increases right after a large earthquake."[12]

Structure

Initially only narrow gauge track was laid through the tunnel, but in 2005 the Hokkaido Shinkansen project started construction which included laying dual-gauge track and extending the Shinkansen network through the tunnel. Shinkansen services to Hakodate are due to commence in March 2016, and are proposed to be extended to Sapporo by 2035. The tunnel has 52 km (32 mi) of continuous welded rail.[13]

Two stations are located within the tunnel itself: Tappi-Kaitei Station and Yoshioka-Kaitei Station. They serve as emergency escape points. In the event of a fire or other disaster, the stations provide the equivalent safety of a much shorter tunnel. The effectiveness of the escape shafts at the emergency stations is enhanced by having exhaust fans to extract smoke, television cameras to help route passengers to safety, thermal (infrared) fire alarm systems, and water spray nozzles.[7] Before the construction of the Hokkaido Shinkansen, both stations contained museums detailing the history and function of the tunnel that could be visited on special sightseeing tours. The museums are now closed and the space provides storage for work on the Hokkaido Shinkansen.[14] The two were the first railway stations in the world built under the sea.

See also

- Seikan Tunnel Tappi Shako Line

- Train on Train, an experimental concept for conveying freight at higher speeds through the tunnel

- JR Freight Class EH800, new AC freight locomotives under development to haul trains through the Seikan Tunnel

- Sakhalin–Hokkaido Tunnel

- Bering Strait crossing

References

- ↑ http://jr.hakodate.jp/global/english/train/tunnel/tunnel_omosiro.htm

- ↑ http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/extreme_machines/4217338.html?series=23

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 Matsuo, S. (1986). "An overview of the Seikan Tunnel Project Under the Ocean". Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 1 (3/4): 323–331. doi:10.1016/0886-7798(86)90015-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Paulson, B. (1981). "Seikan Undersea Tunnel". American Society of Civil Engineers, Journal of the Construction Division 107 (3): 509–525.

- ↑ "Japan Opens Undersea Rail Line". Associated Press. 14 March 1988. p. 6B.

- ↑ Galloway, Peter (25 February 1981). "Japan's super tunnel a political nightmare". Special to The Globe and Mail. p. 15.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Morse, D. (May 1988). "Japan Tunnels Under the Ocean". Civil Engineering 58 (5): 50–53.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Takashima, S. (2001). "Railway Operators in Japan 2: Hokkaido (pdf)". Japan Railway and Transport Review 28: 58–67.

- ↑ "東京―新函館4時間10分 北海道新幹線、16年春開業". Nihon Keizai Shimbun. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Tsuji, H., Sawada, T. and Takizawa, M. (1996). "Extraordinary inundation accidents in the Seikan undersea tunnel". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Geotechnical Engineering 119 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1680/igeng.1996.28131.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kitamura, A. & Takeuchi, Y. (1983). "Seikan Tunnel". Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 109 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(1983)109:1(25).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ikuma, M. (2005). "Maintenance of the undersea section of the Seikan Tunnel". Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 20 (2): 143–149. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2003.10.001.

- ↑ "Seikan Tunnel Museum". 記念館案内 青函トンネル記念館 公式ホームページ. Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- ↑ "March 2006". jrtr.net. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seikan Tunnel. |

- The Seikan Tunnel, Aomori Prefecture Government, version of 3 May 2006 at the Internet Archive

| |||||||||