Seesaw mechanism

In the theory of grand unification of particle physics, and, in particular, in theories of neutrino masses and neutrino oscillation, the seesaw mechanism is a generic model used to understand the relative sizes of observed neutrino masses, of the order of eV, compared to those of quarks and charged leptons, which are millions of times heavier.

There are several types of models, each extending the Standard Model. The simplest version, type 1, extends the Standard Model by assuming two or more additional right-handed neutrino fields inert under the electroweak interactions,[1] and the existence of a very large mass scale. This allows the mass scale to be identifiable with the postulated scale of grand unification.

Type 1 seesaw

This model produces a light neutrino, for each of the three known neutrino flavors, and a corresponding very heavy neutrino for each flavor, which has yet to be observed.

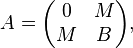

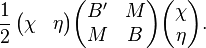

The simple mathematical principle behind the seesaw mechanism is the following property of any 2×2 matrix

where B is taken to be much larger than M.

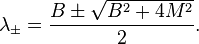

It has two very disproportioned eigenvalues:

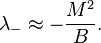

The larger eigenvalue, λ+, is approximately equal to B, while the smaller eigenvalue is approximately equal to

Thus, |M | is the geometric mean of λ+ and −λ−, since the determinant equals λ+λ− = −M 2.

If one of the eigenvalues goes up, the other goes down, and vice versa. This is the point of the name "seesaw" of the mechanism.

This mechanism serves to explain why the neutrino masses are so small.[2][3][4][5][6] The matrix A is essentially the mass matrix for the neutrinos. The Majorana mass B component is comparable to the GUT scale and violates lepton number; while the components M, the Dirac mass, is of order of the much smaller electroweak scale, the VEV below. The smaller eigenvalue λ− then leads to a very small neutrino mass comparable to 1 eV, which is in qualitative accord with experiments, sometimes regarded as supportive evidence for the framework of Grand Unified Theories.

Background

The 2×2 matrix A arises in a natural manner within the standard model by considering the most general mass matrix allowed by gauge invariance of the standard model action, and the corresponding charges of the lepton- and neutrino fields.

Let the Weyl spinor χ be the neutrino part of a left-handed lepton isospin doublet (the other part being the left-handed charged lepton),

as it is present in the minimal standard model without neutrino masses, and let η be a postulated right-handed neutrino Weyl spinor which is a singlet under weak isospin (i.e. does not interact weakly, such as a sterile neutrino).

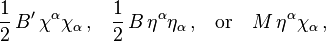

There are now three ways to form Lorentz covariant mass terms, giving either

and their complex conjugates, which can be written as a quadratic form,

Since the right-handed neutrino spinor is uncharged under all standard model gauge symmetries, B is a free parameter which can in principle take any arbitrary value.

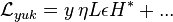

The parameter M is forbidden by electroweak gauge symmetry, and can only appear after its spontaneous breakdown through a Higgs mechanism, like the Dirac masses of the charged leptons. In particular, since χ ∈ L has weak isospin ½ like the Higgs field H, and η has weak isospin 0, the mass parameter M can be generated from Yukawa interactions with the Higgs field, in the conventional standard model fashion,

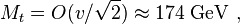

This means that M is naturally of the order of the vacuum expectation value of the standard model Higgs field,

if the dimensionless Yukawa coupling is of order y ≈ 1. It can be chosen smaller consistently, but extreme values y ≫ 1 can make the model nonperturbative.

The parameter B', on the other hand, is forbidden, since no renormalizable singlet under weak hypercharge and isospin can be formed using these doublet components−−only a nonrenormalizable, dimension 5 term is allowed. This is the origin of the pattern and hierarchy of scales of the mass matrix A within the "type 1" seesaw mechanism.

The large size of B can be motivated in the context of grand unification. In such models, enlarged gauge symmetries may be present, which initially force B = 0 in the unbroken phase, but generate a non vanishing large value B ≈ MGUT ≈ 1015 GeV, around the scale of their spontaneous symmetry breaking, so, given an M ≈ 100 GeV, one has λ− ≈ 0.01 eV. A huge scale has thus induced a dramatically small neutrino mass for the eigenvector ν ≈ χ − (M/B) η .

See also

References

- ↑ It is possible to generate two light but massive neutrinos with only one right-handed neutrino, but the resulting spectra are generally not viable.

- ↑ P. Minkowski (1977). "μ --> e γ at a Rate of One Out of 1-Billion Muon Decays?". Physics Letters B 67 (4): 421. Bibcode:1977PhLB...67..421M. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(77)90435-X.

- ↑ M. Gell-Mann, P. Ramond and R. Slansky, in Supergravity, ed. by D. Freedman and P. Van Nieuwenhuizen, North Holland, Amsterdam (1979), pp. 315-321. ISBN 044485438x

- ↑ T. Yanagida (1980). "Horizontal Symmetry and Masses of Neutrinos". Progress of Theoretical Physics 64 (3): 1103–1105. doi:10.1143/PTP.64.1103.

- ↑ R. N. Mohapatra, G. Senjanovic (1980). "Neutrino Mass and Spontaneous Parity Nonconservation". Phys. Rev. Lett. 44 (14): 912–915. Bibcode:1980PhRvL..44..912M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.44.912.

- ↑ J. Schechter, José W. F. Valle; Valle, J. (1980). "Neutrino masses in SU(2) ⊗ U(1) theories". Phys. Rev. 22 (9): 2227–2235. Bibcode:1980PhRvD..22.2227S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.22.2227.