Secondary dominant

Secondary dominant (also applied dominant, artificial dominant, or borrowed dominant) is an analytical label for a specific harmonic device, prevalent in the tonal idiom of Western music beginning in the common practice period. It refers to a dominant seventh chord set to resolve to a degree that is not the tonic, with V7/V, the dominant of the dominant, "being the most frequently encountered".[2] The chord to which a secondary dominant progresses can be thought of as a briefly tonicized chord or pitch (tonicizations longer than a phrase are modulations). "The purpose of the secondary dominant is to place emphasis on a chord within the diatonic progression."[3] "Functioning secondary dominants are used when a composer wants to inject a greater feeling of movement into a diatonic progression."[4] The secondary-dominant terminology is still usually applied even if the chord resolution is nonfunctional (for example if V/ii is not followed by ii).[5]

Definition and notation

The major scale contains seven basic chords, designated with Roman numerals in ascending order. Since the chord on the seventh scale degree is a diminished triad, it is not considered stable, and so only the other six chords may be treated at temporary tonic chords, and so be eligible for an applied dominant. In the key of C major, those six chords are:

Of these chords, V (G major) is said to be the dominant of C major (the dominant of any key is the chord whose root is a fifth above the tonic). However, each of the chords from ii through vi also has its own dominant. For example, vi (A minor) has an E major triad as its dominant. These extra dominant chords are not part of the key of C major as such because they include notes that are not part of the C major scale. Instead, they are the secondary dominants.

Below is an illustration of the secondary-dominant chords for C major. Each chord is accompanied by its standard number in harmonic notation. In this notation, a secondary dominant is usually labeled with the formula "V of ..."; thus "V of ii" stands for the dominant of the ii chord, "V of iii" for the dominant of iii, and so on. A shorter notation, used below, is "V/ii", "V/iii", etc. The secondary dominants are connected with lines to their corresponding tonic chords.

Note that of the above, V/IV is the same as I. However, as will become clear shortly, they are significantly different.

Like most chords, secondary dominants can be classified by whether they contain certain additional notes outside the basic triad; for details, see Figured bass. A dominant seventh chord (notation: V7) is one that contains the note that is a minor seventh above the root, and a dominant-ninth chord (notation: V9) contains the note a ninth above the root. For instance, V7/IV, although it is a C chord, is distinct from regular C major because it also contains the note B flat, which is a minor seventh above the root of C, and not part of the C-major scale.

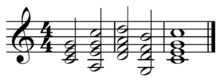

To illustrate, here are the secondary dominants of C major, given as dominant-seventh chords. They are shown leading into their respective tonics, as given in the second inversion.

Chromatic mediants, for example VI is also a secondary dominant of ii (V/ii) and III is V/vi, are distinguished from secondary dominants with context and analysis revealing the distinction.[6]

Normal sequencing or cadence

When used in music, a secondary dominant is very often (though not inevitably) directly followed by the chord of which it is the dominant. Thus V/ii is normally followed by ii, V/vi by vi, and so on. This is similar to the general pattern of music wherein the simple chord V is often followed by I. The tonic is said to "resolve" the slight dissonance created by the dominant. Indeed, the sequence V/X + X, where X is some basic chord, is thought of by some musicians as a tiny modulation, acting as a miniature dominant-tonic sequence in the key of X.

History

Before the 20th century, in music of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms, a secondary dominant, along with its chord of resolution, was considered to be a modulation. Since this was a rather self-contradictory description, theorists in the early 1900s, such as Hugo Riemann (who used the term "Zwischendominante"—"intermediary dominant", still the usual German term for a secondary dominant), searched for a better description of the phenomenon.

Walter Piston first used the analysis "V7 of IV" in a monograph entitled Principles of Harmonic Analysis.[9] (Notably, Piston's analytical symbol always used the word "of"—e.g. "V7 of IV" rather than the virgule "V7/IV.) In his 1941 book Harmony[10] Piston used the term "secondary dominant". At around the same time (1946–48), Arnold Schoenberg created the expression "artificial dominant" to describe the same phenomenon, in his posthumously published book Structural Functions of Harmony.[11]

Mozart example

In the Fifth edition of Harmony by Walter Piston and Mark DeVoto,[12] a passage from the last movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata K. 283 in G major serves as one illustration of secondary dominants. Below, the harmony alone is first given, labeled both for the literal names of the chords and for their chord number in the key of G major.

It can be seen that this passage has three secondary dominants, each one followed (as expected) by the chord of which it is the dominant. The final four bars form a back-cycle, ending in a standard dominant-tonic cadence, which concludes the phrase. The lines drawn below the diagram show each instance in which a dominant is followed by its corresponding tonic.

The harmony is distributed more subtly between the notes, and goes faster, in Mozart's original:

The secondary dominants here create a rapidly descending chromatic harmony, an effective approach to the tonic cadence at the end of the phrase. There are many similar passages in Mozart's music.

Use in jazz

In jazz harmony, a secondary dominant is any dominant chord (major-minor 7th chord) which occurs on a weak beat and resolves downward by a perfect fifth. Thus, a chord is a secondary dominant when it is functioning as the dominant of some harmonic element other than the key's tonic, and promptly resolves to that element. This is slightly different from the traditional use of the term, where a secondary dominant does not have to be a 7th chord, occur on a weak beat, or resolve downward. If a non-diatonic dominant chord is used on a strong beat, it is considered an extended dominant. If it doesn't resolve downward, it may be a borrowed chord.

Secondary dominants are used in jazz harmony in the bebop blues and other blues progression variations, as are substitute dominants and turnarounds.[13]

Popular music

Examples include II7 (V7/V) in Bob Dylan's "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right" and III7 (V7/vi) in Betty Everett's "The Shoop Shoop Song (It's in His Kiss)".[14] "Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue" features chains of secondary dominants.[15]

Extended dominant

An extended dominant is a non-diatonic secondary-dominant seventh chord that resolves downwards to another dominant chord. A series of extended dominant chords continues to resolve downwards by perfect fifths until they reach the tonic chord.

Though typically used in jazz, extended dominants have been used in other contexts as well.

See also

- Barbershop seventh chord

- Backdoor progression

- Circle progression

- ii-V-I turnaround

- Secondary leading-tone chord

- Secondary supertonic chord

Further reading

- Nettles, Barrie & Graf, Richard (1997). The Chord Scale Theory and Jazz Harmony. Advance Music, ISBN 3-89221-056-X

- Thompson, David M. (1980). A History of Harmonic Theory in the United States. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press.

References

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.269. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ↑ Kostka, Stefan and Dorothy Payne (2003). Tonal Harmony, p.250. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-285260-7.

- ↑ Beach, David and McClelland, Ryan C. (2012). Analysis of 18th- and 19th-century Musical Works in the Classical Tradition, p.32. Routledge. ISBN 9780415806657.

- ↑ Wyatt, Keith; Schroeder, Carl; and Joe, Elliott (2005). Ear Training for the Contemporary Musician, p.87. Hal Leonard. ISBN 9780793581931.

- ↑ Rawlins, Robert and Nor Eddine Bahha (2005). Jazzology: The Encyclopedia of Jazz Theory for All Musicians, p.59. ISBN 0-634-08678-2.

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003), p.201-204.

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003), p.277.

- ↑ White, John D. (1976). The Analysis of Music, p.5. ISBN 0-13-033233-X.

- ↑ Walter Piston, Principles of Harmonic Analysis (Boston: E. C. Schirmer, 1933).

- ↑ Walter Piston, Harmony (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1941).

- ↑ Arnold Schoenberg, Structural Functions of Harmony, edited by Humphrey Searle (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1954): 15–29, 197.

- ↑ Walter Piston; Mark DeVoto (1987). Harmony (5th ed. ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-95480-3.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Spitzer, Peter (2001). Jazz Theory Handbook, p.62. ISBN 0-7866-5328-0.

- ↑ Everett, Walter (2009). The Foundations of Rock, p.198. ISBN 978-0-19-531023-8. Everett notates major-minor sevenths Xm7.

- ↑ Shepherd, John (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Volume II: Performance and Production, Volume 11, p.10. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826463227.

- ↑ Boyd, Bill (1997). Jazz Chord Progressions, p.43. ISBN 0-7935-7038-7.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 William G Andrews and Molly Sclater (2000). Materials of Western Music Part 1, p.226. ISBN 1-55122-034-2.

External links

- Secondary dominant construction drill in Javascript

- The Jazz Resource secondary dominant chords in jazz

- Gary Ewer's free lesson on Secondary Dominants

- The Music Theory ProfBlog "Is This a Secondary Function Chord?" flow chart

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||