Second voyage of James Cook

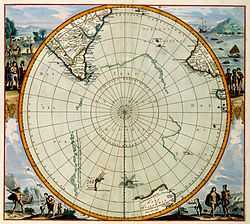

The second voyage of James Cook 1772–1775, commissioned by the British government with advice from the Royal Society,[1] was designed to circumnavigate the globe as far south as possible to finally determine whether there was any great southern landmass, or Terra Australis. On his first voyage, Cook had demonstrated by circumnavigating New Zealand that it was not attached to a larger landmass to the south, and he charted almost the entire eastern coastline of Australia, yet Terra Australis was believed to lie further south. Alexander Dalrymple and others of the Royal Society still believed that this massive southern continent should exist.[2] After a delay brought about by the botanist Joseph Banks' unreasonable demands, the ships Resolution and Adventure were fitted for the voyage and set sail for the Antarctic in July 1772.[3]

On 17 January 1773, Resolution was the first ship to cross the Antarctic Circle which she crossed twice more on the voyage. The third crossing, on 3 February 1774, was to be the most southerly penetration, reaching latitude 71°10′ South at longitude 106°54′ West. Cook undertook a series of vast sweeps across the Pacific, finally proving there was no Terra Australis by sailing over most of its predicted locations.

In the course of the voyage he visited Easter Island, the Marquesas, Tahiti, the Society Islands, Niue, the Tonga Islands, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, Norfolk Island, Palmerston Island, South Sandwich Islands, and South Georgia, many of which he named in the process. Cook proved the Terra Australis Incognita to be a myth[4] and predicted that an Antarctic land would be found beyond the ice barrier.

On this voyage the Larcum Kendall K1 chronometer was successfully employed by William Wales to calculate longitude. Wales compiled a log book of the voyage, recording locations and conditions, the use and testing of various instruments, as well as making many observations of the people and places encountered on the voyage.[5]

Conception

In 1752 a member of the Royal Society of London, Alexander Dalrymple, had found Luis Váez de Torres testimony proving the existence of a passage south of New Guinea now known as Torres Strait, whilst translating some Spanish documents captured in the Philippines. This discovery led Dalrymple to publish An Historical Collection of the Several Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean.[6] in 1770–1771 which aroused widespread interest in his claim of the existence of an unknown continent. Soon after his return from his first voyage in 1771, Commander Cook was commissioned by the Royal Society to make a second voyage in search of the supposed southern continent, Terra Australis Incognita.[7]

Preparation and personnel

Vessels and provisions

Cook commanded HMS Resolution on this voyage, while Tobias Furneaux commanded its companion ship, HMS Adventure. Resolution began her career as the 462 ton North Sea collier Marquis of Granby, launched at Whitby in 1770, purchased by the Royal Navy in 1771 for £4,151, and converted to naval specifications for a cost of £6,565. She was 111 feet (34 m) long and 35 feet (11 m) abeam. She was originally registered as HMS Drake, but fearing this would upset the Spanish, she was renamed Resolution, on 25 December 1771. She was fitted out at Deptford with the most advanced navigational aids of the day, including an azimuth compass made by Henry Gregory, ice anchors and the latest apparatus for distilling fresh water from sea water.[8] Twelve light 6-pounder guns and twelve swivel guns were carried. At his own expense Cook had brass door-hinges installed in the great cabin.[9]

HMS Adventure began her career as the 340 ton North Sea collier Marquis of Rockingham, launched at Whitby in 1771. She was purchased by the Navy that year for £2,103 and named Rayleigh, then renamed Adventure. She was 97 feet (30 m) long, 28 feet (8.5 m) abeam and her draft was 13 feet (4.0 m) and carried ten guns. Both were built at the Fishburn yard at Whitby and purchased from Captain William Hammond of Hull.[10]

Cook was asked to test the Larcum Kendall K1 chronometer on this voyage. The Board of Longitude had asked Kendall to copy and develop John Harrison's fourth model of a clock (H4) useful for navigation at sea. The first model finished by Kendall in 1769 was an accurate copy of H4, cost £450, and is known today as K1. Although constructed like a watch, the chronometer had a diameter of 13 cm and weighed 1.45 kg. Three other clocks, constructed by John Arnold were carried but did not withstand the rigors of the journey.[11] The performance of the clocks was recorded in the logbooks of astronomers William Wales[12] and William Bayly[13] and as early as 1772 Wales had noted that the watch by Kendall was 'infinitely more to be depended on'.[14]

Provisions loaded onto the vessels for the voyage included 59,531 pounds (27,003 kg) of biscuit, 7,637 four-lb pieces of salt beef,14,214 two-lb pieces of salt pork, 19 tuns of beer, 1,397 imperial gallons (6,350 l) of spirits 1,900 pounds (860 kg) of suet and 210 gallons of 'Oyle Olive'. As anti-scorbutics they took nearly 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) of 'Sour Krout' and 30 imperial gallons (140 l) of 'Mermalade of Carrots'. Both ships carried livestock, including bullocks, sheep, goats (for milk), hogs and poultry (including geese). The crews had fishing gear and a water purification system was carried for distilling sea-water or purifying foul fresh-water. Various pieces of hardware (such as knives and axes) and trinkets (beads, ribbons, medallions) to be used for barter or as gifts for the natives were also taken aboard.[11]

Ships' companies

Furneaux, commander of the Adventure, was an experienced explorer, having served on Samuel Wallis's circumnavigation in Dolphin in 1766–1768. He headed a crew of 81 which included Joseph Shank as first lieutenant, and Arthur Kempe as second lieutenant. There were also twelve marines headed by Lieutenant James Scott, Furneaux's personal servant, James Tobias Swilley, and, as master's mate John Rowe who was a relation of Furneaux. The ship's astronomer was William Bayly.

It was originally planned that the naturalist Joseph Banks and what he considered to be an appropriate entourage would sail with Cook, so a heightened waist, an additional upper deck and a raised poop deck were built on the Resolution to suit Banks. This refit cost £10,080 12s 9d. However, in sea trials the ship was found to be top-heavy, and under Admiralty instructions the offending structures were removed in a second refit at Sheerness, at a further cost of £882 3s 0d. Banks subsequently refused to travel under the resulting "adverse conditions." The philosopher Samuel Johnson was briefly considered as a replacement, but declined the offer.[15] Instead the position was taken by Johann Reinhold Forster and his son, George, who were taken on as Royal Society scientists for the voyage. The Resolution carried a crew of 112; as senior lieutenants Robert Cooper and Charles Clerke and two young officers, George Vancouver and James Burney. The master was Joseph Gilbert and Isaac Smith, a relation of Cook's wife was also aboard. William Wales was the astronomer and William Hodges the artist. In all, there were 90 seamen and 18 royal marines as well as the supernumeraries.

Voyage

Cook's first port of call was at Funchal in the Madeira Islands, which he reached on 1 August. Cook gave high praise to his ship's sailing qualities in a report to the Admiralty from Funchal Roads, writing that she "steers, works, sails well and is remarkably stiff and seems to promise to be a dry and very easy ship in the sea."[4] The ship was re-provisioned with fresh water, beef, fruit and onions, and after a further provisioning stop in the Cape Verde Islands two weeks later, set sail due south toward the Cape of Good Hope. The Resolution anchored in Table Bay on 30 October with the crew all in good health because of Cook's imposition of a strict dietary and cleanliness regime. It was here that Swede, Anders Sparrman joined the expedition as a botanist.[16]

The ships left the Cape on 22 November 1772 and headed for the area of the South Atlantic where the French navigator Bouvet claimed to have spotted land that he named Cape Circumcision. Shortly after leaving they experienced severe cold weather and early on 23 November 1772 the crew were issued with fearnaught jackets and trousers at the expense of the government.[17] By early December they were sailing in thick fog and seeing 'ice islands'. Cook had not found the island that Bouvet claimed to be in latitude 54°. Pack ice soon surrounded the ships but in the second week in January, in the southern mid-summer, the weather abated and Cook was able to take the ships southwards through the ice to reach the Antarctic Circle on 17 January. The next day, being severely impeded by the ice, they changed course and headed away to the north-east.[18]

On 8 February 1773 Resolution and Adventure became separated in the Antarctic fog. Furneaux directed Adventure towards the prearranged meeting point of Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand, charted by Cook in 1770. On the way to the rendezvous, Adventure surveyed the southern and eastern coasts of Tasmania (then known as "Van Diemen's Land"), where Adventure Bay was named for the ship. Furneaux made the earliest British chart of this shore, but as he did not enter Bass Strait he assumed Tasmania to be part of Australia. Adventure arrived at Queen Charlotte Sound on 7 May 1773. Cook continued his explorations south-eastwards, reaching 61°21′s on 24 February then, in mid-March he decided to head for Dusky Bay (now Dusky Sound) in the South Island of New Zealand where the ship rested until 30 April. The Resolution reached the rendezvous at Queen Charlotte Sound on 17 May.[19] From June to October the two ships explored the southern Pacific, reaching Tahiti on 15 August, where Omai of Ra'iatea embarked on Adventure (Omai later became the first Pacific Islander to visit Europe before returning to Tahiti with Cook in 1776).

After calling at Tonga in the Friendly Islands the ships returned to New Zealand but were separated by a storm on 22 October. This time the rendezvous at Queen Charlotte Sound was missed — Resolution departed on 26 November, four days before Adventure arrived. Cook had left a message buried in the sand setting out his plan to explore the South Pacific and return to New Zealand. Furneaux decided to return home and buried a reply to that effect. In New Zealand Furneaux lost some of his men during an encounter with Māori, and eventually sailed back to Britain, setting out for home on 22 December 1773 via Cape Horn, arriving in England on 14 July 1774.[19]

Cook continued to explore the Antarctic, heading south into the summer sea ice, icebergs and fog until he reached 67°31′ South before hauling north again for 1,400 miles (2,200 km). The third crossing of the Antarctic Circle, on 26 January 1774, was the precursor to the most southerly penetration, reaching latitude 71°10′ South at longitude 106°54′ West on 30 January when they could go no further because of the solid sea ice.[20] On this occasion, Cook wrote:

I who had ambition not only to go farther than anyone had been before, but as far as it was possible for man to go, was not sorry in meeting with this interruption...

The vessel was then launched north to complete a huge parabola in the Pacific Ocean, reaching latitudes just below the Equator then New Guinea. He had landed at the Friendly Islands, Easter Island, Norfolk Island, New Caledonia, and Vanuatu before returning to Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand.[21]

Homeward voyage

On 10 November 1774 the expedition sailed east over the Pacific and sighted the western end of the Strait of Magellan on 17 December. They spent Christmas in a bay they named Christmas Sound on the western side of Tierra del Fuego. After passing Cape Horn, Cook explored the vast South Atlantic looking for another coastline that had been predicted by Dalrymple. When this failed to materialize they turned north and discovered an island that they named South Georgia. In a last vain attempt to find Bouvet Island Cook discovered the South Sandwich Islands. Here he correctly predicted that:

...there is a tract of land near the Pole, which is the Source of most of the ice which is spread over this vast Southern Ocean.

On 21 March the Resolution anchored in Table Bay, there to spend five weeks as her rigging was refitted. She arrived home at Spithead, Portsmouth on 30 July 1775 having visited St Helena and Fernando de Noronha on the way.[22]

Return home

His reports upon his return home put to rest the popular myth of Terra Australis.[23] Another accomplishment of the second voyage was the successful employment of the Larcum Kendall K1 chronometer, which enabled Cook to calculate his longitudinal position with much greater accuracy. Cook's log was full of praise for the watch which he used to make charts of the southern Pacific Ocean that were so remarkably accurate that copies of them were still in use in the mid-20th century.[24] Cook was promoted to the rank of captain and given an honorary retirement from the Royal Navy, as an officer in the Greenwich Hospital. His acceptance of the post was reluctant, insisting that he be allowed to quit the post if the opportunity for active duty presented itself.[25] His fame now extended beyond the Admiralty and he was also made a Fellow of the Royal Society and awarded the Copley Gold Medal, painted by Nathaniel Dance-Holland, dined with James Boswell and described in the House of Lords as "the first navigator in Europe".[26]

Publication of journals

On his return to England Forster claimed that he had been granted exclusive publication rights to the history of the voyage by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich—a claim that Sandwich vehemently denied. Cook was writing his own account assisted by Dr John Douglas, Canon of Windsor. Eventually, Sandwich agreed that Forster and his son could add a scientific section to Cook's account of the voyage. This led to so much animosity between Forster and Sandwich that Sandwich banned him from writing or publishing anything about the voyage. Forster then avoided the ban by writing a book in his son's name using a draft of Cook's journal which he had earlier acquired. When Forster published his book, six weeks before Cook's own account, it was found to be highly critical of Cook and other members of the voyage, inaccurate and somewhat fabricated. Cook never read the book because it was published after he left on his third voyage.[27]

Legacy

Cook's accounts of the large seal and whale populations helped influence further exploration of the Southern Ocean from sealers in search of the mammals' valued skins.[28] In the 19th century over one thousand sealing ships travelled to the Antarctic regions and its shoreline.

References

- ↑ Williams 2004, p. 51

- ↑ Hough 1994, p. 182

- ↑ "Journal of Captain Cook's voyage round the world in HMS Resolution". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hough 1994, p. 239

- ↑ Wales, William. "Log book of HMS 'Resolution'". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ An Historical Collection of the Several Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean, vol 1, on Archive.org

- ↑ Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 24

- ↑ "Log book of HMS 'Resolution'". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Villiers 1967, p. 160

- ↑ Beaglehole 1974, p. 281

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Villiers 1967, p. 162

- ↑ Wales, William. "Log book of HMS 'Resolution'". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Bayly, William. "Log book of HMS Adventure". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Wales, William. "Log book of HMS 'Resolution'". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Mill, Hugh Robert (September 1936). "The Romance of the Antarctic Seas". Geography (Geographic Association) 21 (3): 187. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ↑ Hough 1994, p. 242

- ↑ Wales, William. "Log book of HMS 'Resolution'". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ Hough 1994, p. 248

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 141

- ↑ Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 45

- ↑ Rigby & van der Merwe 2002, p. 46

- ↑ Collingridge 2002, p. 311

- ↑ Hough 1994, p. 263

- ↑ "Captain James Cook: His voyages of exploration and the men that accompanied him". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ Beaglehole 1974, p. 444

- ↑ Collingridge 2002, pp. 334–335

- ↑ Hough 1994, p. 322

- ↑ "Antarctic History". 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

Bibliography

- Beaglehole, John Cawte (1974). The Life of Captain James Cook. A & C Black. ISBN 0-7136-1382-3.

- Collingridge, Vanessa (February 2003). Captain Cook: The Life, Death and Legacy of History's Greatest Explorer. Ebury Press. ISBN 0-09-188898-0.

- Hough, Richard (1994). Captain James Cook. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-82556-1.

- McLynn, Frank (2011). Captain Cook: Master of the Seas. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11421-8.

- Rigby, Nigel; van der Merwe, Pieter (2002). Captain Cook in the Pacific. National Maritime Museum, London UK. ISBN 0-948065-43-5.

- Robson, John (2004). The Captain Cook Encyclopædia. Random House Australia. ISBN 0-7593-1011-4.

- Villiers, Alan (1967). Captain Cook. The Seaman's Seaman. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-139062-X.

- Williams, Glyndwr (1997). Captain Cook's Voyages: 1768–1779. London: The Folio Society.

- Williams, Glyndwr (2004). Captain Cook: Explorations and Reassessments's. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-100-7.

Further reading

- Edwards, Philip, ed. (2003). James Cook: The Journals. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-043647-2.

Prepared from the original manuscripts by J. C. Beaglehole 1955–67

- Forster, Georg, ed. (1986). A Voyage Round the World. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-05-000180-7.

Published first 1777 as: A Voyage round the World in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, during the Years, 1772, 3, 4, and 5

- Richardson, Brian (2005). Longitude and Empire: How Captain Cook's Voyages Changed the World. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-1190-0.

- Thomas, Nicholas (2003). The Extraordinary Voyages of Captain James Cook. New York: Walker & Co. ISBN 0-8027-1412-9.

- Villiers, Alan (Summer 1956–57). "James Cook, Seaman". Quadrant 1 (1): 7–16.

- Villiers, Alan John (1983) [1903]. Captain James Cook. Newport Beach, CA: Books on Tape.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Cook. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:James Cook. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Captain Cook Society

- Cook's Second Voyage Website of illustrations and maps about Cook's second voyage