Second moment method

In mathematics, the second moment method is a technique used in probability theory and analysis to show that a random variable has positive probability of being positive. More generally, the "moment method" consists of bounding the probability that a random variable fluctuates far from its mean, by using its moments.[1]

The method is often quantitative, in that one can often deduce a lower bound on the probability that the random variable is larger than some constant times its expectation. The method involves comparing the second moment of random variables to the square of the first moment.

First moment method

The first moment method is a simple application of Markov's inequality for integer-valued variables. For a non-negative, integer-valued random variable X, we may want to prove that X = 0 with high probability. To obtain an upper bound for P(X > 0), and thus a lower bound for P(X = 0), we first note that since X takes only integer values, P(X > 0) = P(X ≥ 1). Since X is non-negative we can now apply Markov's inequality to obtain P(X ≥ 1) ≤ E[X]. Combining these we have P(X > 0) ≤ E[X]; the first moment method is simply the use of this inequality.

General outline of the second moment method

In the other direction, E[X] being "large" does not directly imply that P(X = 0) is small. However, we can often use the second moment to derive such a conclusion, using some form of Chebyshev's inequality.

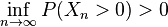

Suppose that Xn is a sequence of non-negative real-valued random variables which converge in law to a random variable X. If there are finite positive constants c1, c2 such that

hold for every n, then it follows from the Paley–Zygmund inequality that for every n and θ in (0, 1)

Consequently, the same inequality is satisfied by X. In many situations, instead of using the Paley–Zygmund inequality, it is sufficient to use Cauchy–Schwarz.

Example application of method

Setup of problem

The Bernoulli bond percolation subgraph of a graph G at parameter p is a random subgraph obtained from G by deleting every edge of G with probability 1−p, independently. The infinite complete binary tree T is an infinite tree where one vertex (called the root) has two neighbors and every other vertex has three neighbors. The second moment method can be used to show that at every parameter p ∈ (1/2, 1] with positive probability the connected component of the root in the percolation subgraph of T is infinite.

Application of method

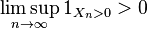

Let K be the percolation component of the root, and let Tn be the set of vertices of T that are at distance n from the root. Let Xn be the number of vertices in Tn ∩ K. To prove that K is infinite with positive probability, it is enough to show that  with positive probability. By the reverse Fatou lemma, it suffices to show that

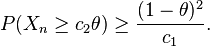

with positive probability. By the reverse Fatou lemma, it suffices to show that  . The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality gives

. The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality gives

Therefore, it is sufficient to show that

that is, that the second moment is bounded from above by a constant times the first moment squared (and both are nonzero). In many applications of the second moment method, one is not able to calculate the moments precisely, but can nevertheless establish this inequality.

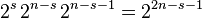

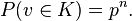

In this particular application, these moments can be calculated. For every specific v in Tn,

Since  , it follows that

, it follows that

which is the first moment. Now comes the second moment calculation.

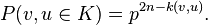

For each pair v, u in Tn let w(v, u) denote the vertex in T that is farthest away from the root and lies on the simple path in T to each of the two vertices v and u, and let k(v, u) denote the distance from w to the root. In order for v, u to both be in K, it is necessary and sufficient for the three simple paths from w(v, u) to v, u and the root to be in K. Since the number of edges contained in the union of these three paths is 2n − k(v, u), we obtain

The number of pairs (v, u) such that k(v, u) = s is equal to  , for s = 0, 1, ..., n. Hence,

, for s = 0, 1, ..., n. Hence,

which completes the proof.

Discussion

- The choice of the random variables Xn was rather natural in this setup. In some more difficult applications of the method, some ingenuity might be required in order to choose the random variables Xn for which the argument can be carried through.

- The Paley–Zygmund inequality is sometimes used instead of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality and may occasionally give more refined results.

- Under the (incorrect) assumption that the events v, u in K are always independent, one has

, and the second moment is equal to the first moment squared. The second moment method typically works in situations in which the corresponding events or random variables are “nearly independent".

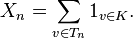

, and the second moment is equal to the first moment squared. The second moment method typically works in situations in which the corresponding events or random variables are “nearly independent". - In this application, the random variables Xn are given as sums

-

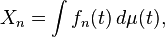

- In other applications, the corresponding useful random variables are integrals

-

- where the functions fn are random. In such a situation, one considers the product measure μ × μ and calculates

-

- where the last step is typically justified using Fubini's theorem.

References

- Burdzy, Krzysztof; Adelman, Omer; Pemantle, Robin (1998), "Sets avoided by Brownian motion", Annals of Probability 26 (2): 429–464, doi:10.1214/aop/1022855639, hdl:1773/2194

- Lyons, Russell (1992), "Random walk, capacity, and percolation on trees", Annals of Probability 20 (4): 2043–2088, doi:10.1214/aop/1176989540

- Lyons, Russell; Peres, Yuval, Probability on trees and networks

- ↑ Terence Tao (2008-06-18). "The strong law of large numbers". What’s new?. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

![E \left [X_n^2 \right ] \le c_1 E[X_n]^2](../I/m/efe387d7a119aa08104cf43858828722.png)

![E \left [X_n \right ]\ge c_2](../I/m/e95055c08ff19dcd3e234dae0801afc5.png)

![E[X_n]^2\le E[X_n^2] \, E\left [(1_{X_n>0})^2\right ]=E[X_n^2]\,P(X_n>0).](../I/m/1c4cec44743f5deb7cd0f25ecad7166a.png)

![\inf_n \frac{E \left[ X_n \right ]^2}{E \left[ X_n^2 \right ]}>0\,,](../I/m/bf00c2424cb1bc3c49b324ba081bf01d.png)

![E[X_n]=2^n\,p^n](../I/m/beb6e1e29449b51b9b22ff05cad1f21b.png)

![E\!\left[X_n^2 \right ] = E\!\left[\sum_{v\in T_n} \sum_{u\in T_n}1_{v\in K}\,1_{u\in K}\right] = \sum_{v\in T_n} \sum_{u\in T_n} P(v,u\in K).](../I/m/9d210014d85b8f8fa463d5ae0feb58b8.png)

![E\!\left[X_n^2 \right ] = \sum_{s=0}^n 2^{2n-s-1} p^{2n-s} = \frac 12\,(2p)^n \sum_{s=0}^n (2p)^s = \frac12\,(2p)^n \, \frac{(2p)^{n+1}-1}{2p-1} \le \frac p{2p-1} \,E[X_n]^2,](../I/m/24f8fc99dee4b11faa04a2ca84658c62.png)

![\begin{align}

E \left[X_n^2 \right ] & = E\left[\int\int f_n(x)\,f_n(y)\,d\mu(x)\,d\mu(y)\right ] \\

& = E\left[ \int\int E\left[f_n(x)\,f_n(y)\right]\,d\mu(x)\,d\mu(y)\right ],

\end{align}](../I/m/ccd3cb8b2035b24449f9d14bed2b6431.png)