Second city of the United Kingdom

The term second city of the United Kingdom requires definition - what constitutes a city, and what is being compared to give the ranking? Comparing conurbations by population, the Greater Manchester Built-up Area is second to the Greater London Built-up Area, but these areas include completely independent towns such as Glossop and Woking. Comparing administrative divisions of the UK, second in population to Greater London is the West Midlands metropolitan county, but this includes the separate conurbation of Coventry. In the UK city status is formally defined, and on that basis the city with the second largest population is Leeds, with Birmingham the largest. Other comparisons require a different definition of a city, or a criterion other than population.

Commonly, a country's second city is the city that is thought to be the second most important, usually after the capital or first city (London, in this case), according to criteria such as population size, economic importance and cultural contribution. The UK has no official second city, nor is there any official mechanism or criteria by which such status could be conferred. Citizens and civic leaders of rival cities often argue over their conflicting claims to this accolade.

Birmingham has generally been regarded as the second city of the United Kingdom, since around the time of World War I,[1] with the largest population and GDP (List of cities by GDP) outside London. Since 2000, however, Manchester has been quoted as the second city in numerous public polls, media references, and global city rankings. The rise has been attributed to Manchester's growing culture, media, music, sporting and transport connections and widespread renovation since the 1996 Manchester bombing.[2]

Edinburgh,[3] Belfast[4] and Cardiff have a claim on the title of "second city" by virtue of their status as the respective capital cities of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales.

Other cities in both England and Scotland have at times been considered the second city. For example, Liverpool in the past was nicknamed the "Second City of the Empire"[5] and was also the world's first global city.[6] During the 19th and early 20th century, the whole of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, and during some of this time Dublin was considered to be the second city.[7][8] Glasgow and Leeds are other major contenders.

It is perhaps even more difficult to make a distinction based on cultural factors, as all major UK cities play an important role in the cultural make-up of the country. Birmingham, Manchester, Edinburgh, Glasgow (European Capital of Culture for 1990), Liverpool (joint European Capital of Culture for 2008), Leeds, Sheffield, Bristol, Cardiff, Newcastle upon Tyne, Sunderland, Portsmouth, Southampton, Plymouth, Kingston upon Hull, Bradford and others all boast internationally recognised sporting, music and performing arts scenes.

History

Since the formation of the United Kingdom, several places have been described as the "second city". Dublin was the second most populous city at the time of the formation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, though it lost that position later in the 19th century as other cities grew through more rapid industrialisation.[9] As such, it was often described as the second city of the UK.[7] Dublin, and the rest of the Republic of Ireland, became independent of the UK in the 1920s.

The title Second City of Empire or Second City of the British Empire was claimed by a number of cities in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. Commercial trading city Liverpool was regarded as holding this title with its massive port, merchant fleet and world-wide trading links.[5][10][11] Liverpool was constantly referred to as the New York of Europe.[12] Others included Dublin,[13] Glasgow (which continues to use the title as a marketing slogan),[14][15] and (outside the UK) Kolkata (known as Calcutta during the British Empire)[16] and Philadelphia.[17]

Prior to the union with Scotland in 1707, from the English Civil War until the 18th century, Norwich was the second-largest city of England, being a major trading centre, Britain's richest provincial city and county town of Norfolk, at that time the most populous county of England.[18] Bristol was the second wealthiest city in England in the 16th century;[19] and by the 18th century, Bristol was often described as the second city of England.[20] During the 19th century, claims were made for Manchester,[21] Liverpool[22] and York.[23] York had also been named as the second city in earlier centuries.[24]

By the early 19th century, Glasgow was frequently referred to as the second city;[25] and during much of the 20th century it had a population of over one million, larger than that of Birmingham until the 1951 census. For example, the Official Census population for Glasgow was 0.784 million in April 1911; 1.034 million in April 1921; 1.088 million in April 1931 and 1.090 million in April 1951.[26] However, slum clearances in the 1960s led to displacement of residents from the city centre to new communities located outside the city boundaries. This, together with local government reorganisation, resulted in the official population of Glasgow falling sharply. The Glasgow City Council area currently has a population of 600,000 although the surrounding conurbation of Greater Glasgow has a population of 1,199,629.[27] In contrast, the population of the city of Birmingham has remained steady around the one million mark; its central population fell like Glasgow's, but the city boundaries were extended several times in the early 20th century. Occasional claims were made for Liverpool,[28] Birmingham[29] and Manchester.[30]

Modern points of view

Since World War I, and up to the beginning of the 21st century, Birmingham had been considered by many to be the second city, but recent polls and media references have indicated that Manchester is now considered to be the second city of the United Kingdom.

In a 2007 survey commissioned by the BBC investigating the subject of the "'Second city' of England" (as opposed to the UK as a whole), 48% of 1,000 people placed Manchester, with 40% choosing Birmingham.[31][32] The BBC further reported that Manchester is close to being the second city of the UK in 2005.[33] In a similar survey conducted by Ipsos MORI, commissioned by "Visit Manchester" (Manchester's tourism department), Manchester received the highest response for the category of second city at 34%, compared to Birmingham at 29%; and in the same poll, Manchester had the highest response for the category of third city with 27% of the vote, 6% more than the 21% for Birmingham.[34] Only 85% of respondents put London as first City.[35]

HSBC commissioned an intensive study of the growth of UK cities in 2009 (updated in mid-2011) which determined that there will be seven super-cities, with Manchester and Birmingham excluded:[36][37]

- Brighton – The capital of the UK's rebellious, alternative economy

- Bristol – Pioneering new material to become a centre of advanced manufacturing

- Glasgow – A leading international force in the renewable energy sector

- Leeds – A provincial hub of financial companies and ancillary services

- Liverpool – A dynamic centre of cultural and branding businesses

- London – A city state, where the creative sector will take a pre-eminent position

- Newcastle – A science city producing world class scientific research

Based on population within actual city boundaries the City of Birmingham, the most populous local government district in Europe, is substantially larger than the City of Manchester, which is the fifth largest in the UK (2006 estimates, see List of English districts by population). However, most sources do not use formal city boundaries as the sole criterion for population comparison: for instance, the City of London, with a population of only 7,185 (2001 census), is very small, though London as a whole is the most populous city within city limits in the European Union[38] with an official population of 7.6 million (as of 2006) and has a metropolitan area with a population of between 12 million[39] and 14 million.[40]

The surrounding conurbations and the areas that can be considered informally part of each city are hard to define. However after the 1974 reorganisation of local government and the creation of metropolitan counties, the City of Birmingham was included with the City of Coventry and five other metropolitan boroughs (one, Wolverhampton gained city status in 2000) in a new West Midlands county. The City of Manchester joined with the neighbouring City of Salford and eight other Metropolitan boroughs within the County of Greater Manchester.

While the 'second city' status of any country is decided upon a variety of economic or cultural indices, both Birmingham and Manchester have shown an edge in each over the years. For example in 2010, Manchester City Centre became second to London for new office building take-up with almost a million square foot (86,399 km2) occupied in the year,[41] whilst praise for Birmingham's striking modern architecture was cited as confirmation of its claim to second city status.[42]

There have been a variety of Ministerial opinions on the subject for some time. These include:

- In February 2015 UK Prime Minister David Cameron stated "We recognise Birmingham’s status as Britain’s second city as a powerhouse..."[43]

- David Miliband, the former Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and former Shadow Foreign Secretary said "However, if you look at Birmingham, I think a lot of people would say that it's a city, Britain's second city..."[44]

- Digby Jones, Baron Jones of Birmingham (born and raised in Birmingham), former Minister of State at the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform and the Foreign Office (former Director-General of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) said "Birmingham is naturally the second most important city in Britain after London because of where she is and how important she is as part of that crossroads,".[45] Jones later said "As a Brummie it's not easy to say, but I can find no better place than the north west in terms of having a diverse manufacturing base, whether it's engineering manufacturing at Rolls-Royce, automotive manufacturing at Bentley or pharmaceuticals manufacturing at AstraZeneca." which contradicts what he said about Birmingham being the most important base outside London. He also praised "Manchester's 'first-class global' university, knowledge and transport infrastructure were the two key factors that determined the success of a city or region."[46] In 2011, Jones stated that Birmingham is now in danger of losing its unofficial title to Manchester[47]

- John Prescott (born in Wales and raised in Cheshire), former Deputy Prime Minister and Member of Parliament for the constituency of Hull East, was also quoted as saying "Manchester – our second city", but this was later played down by his department, claiming they were made in a "light-hearted context".[48]

- Graham Stringer (born and raised in and currently representing Manchester), MP for Blackley and Broughton, responded with "Manchester has always been the second city after the capital, in many ways it is the first. Birmingham has never really been in the competition."[48]

- Sandra White (born and raised in and representing Glasgow), a Scottish National Party MSP for Glasgow, claimed "Glasgow was always seen as the second city in the Empire, and Glasgow is still the second British city. Manchester is probably the second city in England after London."[48]

- Phil Woolas (born in Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire, living in Lees, Greater Manchester and representing the constituency of Oldham East and Saddleworth), Former Minister of State for the Environment – "And, of course, I, and colleagues in Manchester, am pleased to see its very sensible plans to relocate to Manchester – Britain's third city."[49]

Candidates in alphabetical order

Belfast

Belfast (Irish: Béal Feirste, "mouth of the sandbars") is the capital of and the largest city in Northern Ireland and the second largest city in Ireland. It is the seat of devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly.[50] The city forms part of the largest urban area in Northern Ireland, and the main settlement in the province of Ulster. The city of Belfast has a population of 267,500 and lies at the heart of the Belfast urban area, which has a population of 483,418. The Larger Urban Zone, as defined by the European Union, has a total population 641,638. Belfast was granted city status in 1888.

Historically, Belfast has been a centre for the Irish linen industry (earning the nickname "Linenopolis"), tobacco production, rope-making and shipbuilding: the city's main shipbuilders, Harland and Wolff, which built the ill-fated RMS Titanic, propelled Belfast on to the global stage in the early 20th century as the largest and most productive shipyard in the world. Belfast played a key role in the Industrial Revolution, establishing its place as a global industrial centre until the latter half of the 20th century.

Industrialisation and the inward migration it brought made Belfast, if briefly, the largest city in Ireland at the turn of the 20th century and the city's industrial and economic success was cited by Ulster unionist opponents of Home Rule as a reason why Ireland should shun devolution and later why Ulster in particular would fight to resist it.

Today, Belfast remains a centre for industry, as well as the arts, higher education and business, a legal centre, and is the economic engine of Northern Ireland. The city suffered greatly during the period of disruption, conflict, and destruction called the Troubles, but latterly has undergone a sustained period of calm, free from the intense political violence of former years, and substantial economic and commercial growth. Belfast city centre has undergone considerable expansion and regeneration in recent years, notably around Victoria Square.

Belfast is served by two airports: George Best Belfast City Airport in the city, and Belfast International Airport 15 miles (24 km) west of the city. Belfast is also a major seaport, with commercial and industrial docks dominating the Belfast Lough shoreline, including the famous Harland and Wolff shipyard. Belfast is a constituent city of the Dublin-Belfast corridor, which has a population of 3 million, or half the total population of the island of Ireland.

Birmingham

Birmingham (![]() i/ˈbɜrmɪŋəm/ BUR-ming-əm, locally /ˈbɜrmɪŋɡəm/ BUR-ming-gəm) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London with 1,073,000 residents (2011 census), an increase of 96,000 over the previous decade.[51] The city lies within the West Midlands conurbation, the third most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a population of 2,440,986 (2011 census)[52] Its metropolitan area is also the United Kingdom's second most populous with 3,683,000 residents.[53]

i/ˈbɜrmɪŋəm/ BUR-ming-əm, locally /ˈbɜrmɪŋɡəm/ BUR-ming-gəm) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London with 1,073,000 residents (2011 census), an increase of 96,000 over the previous decade.[51] The city lies within the West Midlands conurbation, the third most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a population of 2,440,986 (2011 census)[52] Its metropolitan area is also the United Kingdom's second most populous with 3,683,000 residents.[53]

A medium-sized market town during the medieval period, Birmingham grew to international prominence in the 18th century at the heart of the Midlands Enlightenment and subsequent Industrial Revolution, which saw the town at the forefront of worldwide developments in science, technology and economic organisation, producing a series of innovations that laid many of the foundations of modern industrial society.[54] By 1791 it was being hailed as "the first manufacturing town in the world".[55] Birmingham's distinctive economic profile, with thousands of small workshops practising a wide variety of specialised and highly skilled trades, encouraged exceptional levels of creativity and innovation and provided a diverse and resilient economic base for industrial prosperity that was to last into the final quarter of the 20th century.[56] Its resulting high level of social mobility also fostered a culture of broad-based political radicalism, that under leaders from Thomas Attwood to Joseph Chamberlain was to give it a political influence unparalleled in Britain outside London and a pivotal role in the development of British democracy.[57]

Today Birmingham is a major international commercial centre, ranked as a beta− world city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network;[58] and an important transport, retail, events and conference hub. With a GDP of $90bn (2008 estimate, PPP), the economy of the urban area is the second largest in the UK and the 72nd largest in the world.[59] Birmingham's six universities make it the largest centre of higher education in the United Kingdom outside London,[60] and its major cultural institutions, including the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the Birmingham Royal Ballet and the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, enjoy international reputations.[61] The Big City Plan is a large redevelopment plan currently underway in the city centre with the aim of making Birmingham one of the top 20 most liveable cities in the world within 20 years.[62]

Cardiff

Cardiff (![]() i/ˈkɑːdɪf/; Welsh: Caerdydd ) is the capital, largest city and most populous county of Wales. The city is Wales' chief commercial centre, the base for most national cultural and sporting institutions, the Welsh national media, and the seat of the National Assembly for Wales. According to recent estimates, the population of the unitary authority area is 324,800, while the wider metropolitan area has a population of nearly 1.1 million, more than a third of the total Welsh population.[63] Cardiff is a significant tourism centre and the most popular visitor destination in Wales with 14.6 million visitors in 2009.[64]

i/ˈkɑːdɪf/; Welsh: Caerdydd ) is the capital, largest city and most populous county of Wales. The city is Wales' chief commercial centre, the base for most national cultural and sporting institutions, the Welsh national media, and the seat of the National Assembly for Wales. According to recent estimates, the population of the unitary authority area is 324,800, while the wider metropolitan area has a population of nearly 1.1 million, more than a third of the total Welsh population.[63] Cardiff is a significant tourism centre and the most popular visitor destination in Wales with 14.6 million visitors in 2009.[64]

The city of Cardiff is the county town of the historic county of Glamorgan (and later South Glamorgan). Cardiff is part of the Eurocities network of the largest European cities.[65] The Cardiff Urban Area covers a slightly larger area outside of the county boundary, and includes the towns of Dinas Powys, Caerphilly, Penarth, Pontypridd and Radyr.[52] A small town until the early 19th century, its prominence as a major port for the transport of coal following the arrival of industry in the region contributed to its rise as a major city.

Cardiff was made a city in 1905, and proclaimed capital of Wales in 1955. Since the 1990s Cardiff has seen significant development with a new waterfront area at Cardiff Bay which contains the Senedd building, home to the Welsh Assembly and the Wales Millennium Centre arts complex.

Sporting venues in the city include the Millennium Stadium (the national stadium for the Wales national rugby union team and the Wales national football team), SWALEC Stadium (the home of Glamorgan County Cricket Club), Cardiff City Stadium (the home of Cardiff City football team), Cardiff International Sports Stadium (the home of Cardiff Amateur Athletic Club) and Cardiff Arms Park (the home of Cardiff Rugby Club and Cardiff Blues rugby union team). The city was awarded with the European City of Sport in 2009 due to its role in hosting major international sporting events.

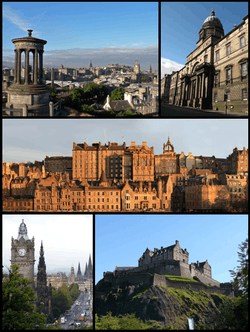

Edinburgh

Edinburgh (![]() i/ˈɛdɪnbʌrə/ ED-in-burr-ə; Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Èideann) is a city in South East Scotland, on the southern shore of the Firth of Forth. It is the principal settlement in Lothian and the seat of the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament. With a population of 495,360 in 2011 (up 1.9% from 2010),[66] the city lies at the centre of a larger urban zone of approximately 850,000 people.[67]

i/ˈɛdɪnbʌrə/ ED-in-burr-ə; Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Èideann) is a city in South East Scotland, on the southern shore of the Firth of Forth. It is the principal settlement in Lothian and the seat of the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament. With a population of 495,360 in 2011 (up 1.9% from 2010),[66] the city lies at the centre of a larger urban zone of approximately 850,000 people.[67]

Each August the city hosts the biggest annual international arts festival in the world. This includes the Edinburgh International Festival, Edinburgh Festival Fringe and the Edinburgh International Book Festival. Other festivals are held throughout the year, such as the Science Festival, Film Festival and Jazz and Blues Festival. Other annual events include the Hogmanay street party and Beltane.

Edinburgh is the world's first UNESCO City of Literature[68] and the city's Old Town and New Town are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[69] It is considered one of the most beautiful cities in the world and regularly polls as one of the best places to live, having won more than 12 UK Best City Awards in 8 years to 2013.[70]

Attracting over one million overseas visitors a year, Edinburgh is the second most popular tourist destination in the UK (after London)[71] and was voted European Destination of the Year at the World Travel Awards 2012.

Glasgow

Glasgow (![]() i/ˈɡlæzɡoʊ/ GLAZ-goh; Scots: Glesga

i/ˈɡlæzɡoʊ/ GLAZ-goh; Scots: Glesga ![]() listen ; Scottish Gaelic: Glaschu, pronounced [ˈkɫ̪as̪xu]) is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands. A person from Glasgow is known as a Glaswegian.

listen ; Scottish Gaelic: Glaschu, pronounced [ˈkɫ̪as̪xu]) is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands. A person from Glasgow is known as a Glaswegian.

Glasgow grew from the medieval Bishopric of Glasgow and the later establishment of the University of Glasgow in the 15th century, which subsequently became a major centre of the Scottish Enlightenment in the 18th century. From the 18th century the city also grew as one of Britain's main hubs of transatlantic trade with British North America and the British West Indies. With the Industrial Revolution, the city and surrounding region shifted to become one of the world's pre-eminent centres of heavy engineering, most notably in the shipbuilding and marine engineering industry, which produced many innovative and famous vessels. Glasgow was known as the "Second City of the British Empire" for much of the Victorian era and Edwardian period.[72][73][74][75] Today it is one of Europe's top twenty financial centres and is home to many of Scotland's leading businesses.[76] Glasgow is also ranked as the 57th most liveable city in the world.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Glasgow grew to a population of over one million,[77] and was the fourth-largest city in Europe, after London, Paris and Berlin.[78] In the 1960s, large-scale relocation to new towns and peripheral suburbs, followed by successive boundary changes, have reduced the current population of the City of Glasgow unitary authority area to 580,690,[79] with 1,199,629[27] people living in the Greater Glasgow urban area. The entire region surrounding the conurbation covers approximately 2.3 million people, 41% of Scotland's population.[80]

Leeds

Leeds, a city and metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England.[81] In 2001 Leeds's main urban subdivision had a population of 443,247,[82] while the entire city had a population of 770,800 (2008 est.) making it the third largest in the country.[83] Leeds is the cultural, financial and commercial heart of the West Yorkshire Urban Area,[84][85] which at the 2011 census had a population of 1.8 million.[52] Leeds is the UK's largest centre for business, legal, and financial services outside London.[86] The Bank of England have their only offices outside London in Leeds.

The contemporary economy of Leeds has been shaped by Leeds City Council having the vision of building a '24-hour European city' and a 'capital of the north'. It has developed from the decay of the post-industrial era to become a telephone banking centre, connected to the electronic infrastructure of the modern global economy.There has been growth in the corporate and legal sectors and increased local affluence has led to an expanding retail sector, including the luxury goods market. Leeds was voted 'Britain's Best City for Business' by OMIS Research in 2003[87] but dropped to 3rd place behind Manchester and Glasgow in 2005 ("Relative under-performance over the past two years in transport improvements and cost competitiveness were the major contributing factors"). It is also regarded by some as one of the fastest growing cities in the UK.

Over 124,000 people work in financial and business services in Leeds, the largest number of any UK city outside London. The strength of the economy is also indicated by the low unemployment rate. Although Leeds's economy has boomed in recent years, the prosperity has not spread to all parts of the city.

Leeds has an extensive and diverse range of shops and department stores, and has been described by the Lonely Planet guides as the 'Knightsbridge of the North'. The diverse range of shopping facilities, from individual one-off boutiques to large department stores such as Harvey Nichols and Louis Vuitton outlets, has greatly expanded the Leeds retail base.

In terms of culture, Leeds is the only English city outside London with its own repertory theatre, opera house and ballet companies. The West Yorkshire Playhouse also stages more productions each year than any other theatre outside London.[88]

Liverpool

Liverpool (pronounced /ˈlɪvɚpuːl/) is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880. Historically a part of Lancashire, the urbanisation and expansion of Liverpool were both largely brought about by the city's status as a major port. By the 18th century, trade from the West Indies, Ireland and mainland Europe coupled with close links with the Atlantic Slave Trade furthered the economic expansion of Liverpool. By the early 19th century, 40% of the world's trade passed through Liverpool's docks, contributing to Liverpool's rise as a major city. The Liverpool City Region has a population of 2.3 million people. A map of the region is in The North West of England Plan Regional Spatial Strategy to 2021.[89][90]

For periods during the 19th century the wealth of Liverpool exceeded that of London itself,[91] and Liverpool's Custom House was the single largest contributor to the British Exchequer.[92] Liverpool's status can be judged from the fact that it was the only British city ever to have its own Whitehall office.[93] Even today Liverpool tops all cities outside London for wealth management. Compounded by other towns and cities in this field in the Liverpool City Region such as, Chester, Bootle and Skelmersdale, the region holds a strong grip.[94]

Liverpool's status as a port city has contributed to its diverse population, which, historically, were drawn from a wide range of peoples, cultures, and religions. The city is also home to the oldest Black African community in the country and the oldest Chinese community in Europe.

Liverpool is noted for its rich architectural heritage and is home to many buildings regarded as amongst the greatest examples of their respective styles in the world. Several areas of the city centre were granted World Heritage Site status by UNESCO in 2004. Referred to as the Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City, the site comprises six separate locations in the city including the Pier Head, Albert Dock and William Brown Street and includes many of the city's most famous landmarks.[95]

Liverpool's history means that there are a considerable variety of architectural styles found within the city, ranging from 16th century Tudor buildings to modern-day contemporary architecture.[96] The majority of buildings in the city date from the late-18th century onwards, the period during which the city grew into one of the foremost powers in the British Empire.[97] There are over 2,500 listed buildings in Liverpool, of which 27 are Grade I listed[98] and 85 are Grade II* listed.[99] The city also has a greater number of public sculptures than any other location in the United Kingdom aside from Westminster[100] and more Georgian houses than the city of Bath.[101] This richness of architecture has subsequently seen Liverpool described by English Heritage, as England's finest Victorian city.[102]

Spearheaded by the multi-billion Liverpool ONE development, regeneration has continued on an unprecedented scale through to the start of the early 2010s in Liverpool. Some of the most significant regeneration projects to have taken place in the city include the new Commercial District, King's Dock, Mann Island, the Lime Street Gateway, the Baltic Triangle, RopeWalks and the Edge Lane Gateway. All projects could however soon be eclipsed by the Liverpool Waters scheme which if built will cost in the region of £5.5billion and be one of the largest megaprojects in the UK's history. Liverpool Waters is a mixed use development which will contain one of Europe's largest skyscraper clusters. The project received outline planning permission in 2012.[103] A similar project Wirral Waters is planned for the opposite bank of the River Mersey.

A planned Post-Panamax container terminal extension will berth the world's largest container ships on the tidal River Mersey side of Seaforth Dock. These ships transport up to 14,000 containers per ship. This facility will increase container throughput by over 100%, from 700,000 containers per annum to 2 million by 2020. The city's new cruise liner terminal, which is situated close to the Pier Head, also makes Liverpool one of the few places in the world where cruise ships are able to berth in the centre of the city.[104] No other regional city has many large scale expansion projects.

Another important component of Liverpool's economy are the tourism and leisure sectors. Liverpool is the 6th most visited city in the United Kingdom[105] and one of the 100 most visited cities in the world by international tourists.[106] In 2008, during the city's European Capital of Culture celebrations, overnight visitors brought £188m into the local economy,[105] while tourism as a whole is worth approximately £1.3bn a year to Liverpool.[107] Other recent developments in Liverpool such as the Echo Arena and Liverpool One have made Liverpool an important leisure centre with the latter helping to lift Liverpool into the top five retail destinations in the UK.[108]

The popularity of The Beatles and the other groups from the Merseybeat era contributes to Liverpool's status as a tourist destination. The city celebrated its 800th anniversary in 2007, and it held the European Capital of Culture title together with Stavanger, Norway, in 2008. Several areas of the city centre were granted World Heritage Site status by UNESCO in 2004. Referred to as the Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City, the site comprises six separate locations in the city including the Pier Head, Albert Dock and William Brown Street and includes many of the city's most famous landmarks.

The city is one of only four cities in the UK with its own partially underground rapid-transit urban rail network, Merseyrail, serving the two terminal rail stations at Lime Street railway station and Chester which both terminate London trains. The city has its own airport, Liverpool John Lennon Airport.

Manchester

Manchester ![]() i/ˈmæntʃɛstər/ is a city and metropolitan borough in North West England with an estimated population of 503,000.[109] Manchester lies within the United Kingdom's second largest urban area which has a population of 2.6 million.[52] People from Manchester are known as Mancunians and the local council is Manchester City Council, although Salford City Council areas lie within the scope of the city centre. There are number of other councils with close expanse and parts of both Metropolitan Borough of Bury and Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council home to Manchester United Football Club lie within 2 miles of the city centre. Manchester is situated in the south-central part of North West England, fringed by the Cheshire Plain to the south and the Pennines to the north and east. Manchester is has also been named a Beta Global city, in the global rankings of the most important to the global economic system. Making it the highest rated city in the UK outside of London.

i/ˈmæntʃɛstər/ is a city and metropolitan borough in North West England with an estimated population of 503,000.[109] Manchester lies within the United Kingdom's second largest urban area which has a population of 2.6 million.[52] People from Manchester are known as Mancunians and the local council is Manchester City Council, although Salford City Council areas lie within the scope of the city centre. There are number of other councils with close expanse and parts of both Metropolitan Borough of Bury and Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council home to Manchester United Football Club lie within 2 miles of the city centre. Manchester is situated in the south-central part of North West England, fringed by the Cheshire Plain to the south and the Pennines to the north and east. Manchester is has also been named a Beta Global city, in the global rankings of the most important to the global economic system. Making it the highest rated city in the UK outside of London.

The recorded history of Manchester began with the civilian settlement associated with the Roman fort of Mamucium, which was established in c. 79 AD on a sandstone bluff near the confluence of the rivers Medlock and Irwell. Historically, most of the city was a part of Lancashire, although areas south of the River Mersey were in Cheshire.[110] Throughout the Middle Ages Manchester remained a manorial township, but it began to expand "at an astonishing rate" around the turn of the 19th century. Manchester's unplanned urbanisation was brought on by a boom in textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution,[111] and resulted in it becoming the world's first industrialised city.[112] An early-19th-century factory building boom transformed Manchester from a township into a major mill town, nicknamed 'cottonopolis', and borough that was granted city status in 1853. In 1877, the Manchester Town Hall was built and in 1894 the Manchester Ship Canal was opened, creating the Port of Manchester. Today Manchester is ranked as a beta world city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network;[58]

The city is notable for its architecture, culture, music scene, media links, scientific and engineering output, social impact and sporting connections. Manchester's sports clubs include Premier League football teams, Manchester City and Manchester United.[113] Manchester was the site of the world's first railway station, and the place where scientists first split the atom and developed the first stored-program computer. Manchester is served by three universities, including the largest single-site university in the UK, and has the country's third largest urban economy.[59] Manchester is also the third-most visited city in the UK by foreign visitors, after London and Edinburgh, and the most visited in England outside London.[114] Manchester Airport is also the largest after London Heathrow and Gatwick airports, offering a number of long-haul worldwide destinations.

An organisation titled Manchester:Knowledge Capital (M:KC for short) has partnered with universities, local and Regional Government, trade associations and leading businesses in the area to promote Manchester and maintain its national and international position as a leading 21st-century city.

According to the 2011 census Manchester's urban area had a population of 2.55m compared to 2.44m for Birmingham[52] The 2011 census also confirmed Manchester as the fastest growing city outside of London population rise with a population rise of 19% (Birmingham 9%), although there was a larger increase in population numbers in Birmingham over Manchester.[115][116]

See also

References

- ↑ Hopkins, Eric (2001). Birmingham: The Making of the Second City 4850-1939. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2327-4.

- ↑ "Manchester tops second city poll". BBC News. 10 February 2007.

- ↑ New York Times, August 6, 1989: "Edinburgh's castle high on the rock has looked down on many a triumph and tragedy in the proud Scots capital, but every year since 1947, Britain's Second City steals the spotlight from London during the three weeks of the international festival."

- ↑ Hoge, Warren (25 June 2003). "LETTER FROM EUROPE; The Last Hard Case: Bleak, Stubborn Belfast". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The Empire in one city?". Manchester University Press. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ "Global City – Museum of Liverpool". Liverpoolmuseums.org.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sidney Edwards Morse and Jedidiah Morse, A New System of Geography, Ancient and Modern, p.177, 1824

- ↑ Provincial Towns in Early Modern England and Ireland: Change, Convergence, and Divergence, Oxford University Press, p.22, 2002

- ↑ BBC: "A Short History of Ireland" – "The population, which had been 58,000 in 1683, was close to 129,000 by 1772 and 182,000 including the garrison by 1798, making Dublin the second largest city in the British Empire."

- ↑ http://www.liv.ac.uk/researchintelligence/issue30/liverpool800.html Liverpool University: "... the city's pre-eminent position at the turn of the 19th century resulted from the port's willingness to handle a very wide range of cargo (including millions of migrants to the new world). Liverpool was second only to London in this respect – and this, together with its great ethnic diversity, was the basis of its claim to being the 'second city of empire'."

- ↑ Untitled Document

- ↑ "Port of Liverpool contact information". Worldportsource.com. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "When you remember that Dublin has been a capital for thousands of years, that it is the second city of the British Empire, that it is nearly three times as big as Venice it seems strange that no artist has given it to the world." James Joyce, Letter to Stanislaus Joyce, c. 24 September 1905 (Letters of James Joyce, vol. II, pp. 109–112. (Viking Press, 1966).

- ↑ "The Second City". Glasgow City Council (glasgow.gov.uk).

- ↑ Fraser, W Hamish. "Second City of The Empire: 1830s to 1914". The Glasgow Story.

- ↑ Tourism of India – Special Feature – Relics of the Raj

- ↑ "Philadelphia, Pennsylvania facts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania travel videos, flags, photos". National Geographic. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Laura; Jones, Alexandra; Lee, Neil; Griffiths, Simon. "Enabling Norwich in the Knowledge Economy" (PDF). The Work Foundation web pages. The Work Foundation. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ↑ J. E. T. and A. G. L. Rogers, A History of Agriculture and Prices in England, p.82, 1887

- ↑ Charles Knight, The Popular History of England, p.8, 1859

- ↑ Robert Southey, Letters from England, p.177, 1836

- ↑ James Richard Joy, An Outline History of England, p.26, 1890

- ↑ John Major, Aeneas James George Mackay and Thomas Graves Law, A History of Greater Britain as Well England as Scotland, p.xxxvi, 1892

- ↑ John Macky, A Journey Through England, p.208, 1722

- ↑ For example, see T. H. B. Oldfield, The Representative History of Great Britain and Ireland, p.566, 1816 or Spencer Walpole, A History of England from the Conclusion of the Great War in 1815, p.103, 1878

- ↑ Roberson, D. J. (1958). "Population, Past and Present". Chapter 2 in: Cunnison, J. and Gilfillan, J. B. S. (1958). The Third Statistical Account of Scotland, Volume V. The City of Glasgow. Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Key Statistics for Settlements and Localities Scotland". General Register Office for Scotland. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ↑ D. Appleton, Appletons' American Standard Geographies, p.130, 1881.

- ↑ W. Stewart & Co., The Journal of Education, p.38, 1867.

- ↑ Chetham Society, Remains, Historical and Literary, Connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancashire and Chester, 1862, p.531.

- ↑ "Manchester tops second city poll". BBC NEWS. 10 February 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ↑ "Birmingham Versus Manchester". YouTube. 10 February 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Manchester 'close to second city'". BBC NEWS. 29 September 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2006.

- ↑ "// Visit Manchester / Homepage //". Destinationmanchester.com. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Manchester 'England's second city'". Ipsos MORI North. 2002. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ↑ "New British Landscape Unveiled 2011". Business Banking Newsroom | HSBC Bank UK. 1 August 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Griffiths, Katherine (2 June 2011). "Super-cities will help Britain take on the world". The Times. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "National Statistics Online". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "The Principal Agglomerations of the World". City Population. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ↑ "British urban pattern: population data" (PDF). ESPON project 1.4.3 Study on Urban Functions. European Spatial Planning Observation Network. March 2007. p. 119. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ "Commercial property will continue to prosper in 2011 – Manchester Evening News". Menmedia.co.uk. 3 January 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Birmingham: Britain’s second city | EuroCheapo's Travel Tips

- ↑ "Cameron: Birmingham is England's second city". Birmingham Post (Trinity Mirror). 13 February 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ "New Labour troubles". BBC Sunday AM (BBC). 5 March 2005. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ "Manchester tops second city poll". BBC News (BBC). 9 February 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ↑ "Jones: North west best for innovation". Manchester Evening News. 10 April 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ↑ Leading Article: Second Best, www.independent.co.uk. accessed 18 May 2011

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 "Prescott ranks Manchester as second city". Manchester Evening News (M.E.N media). 3 February 2005. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

We have had fantastic co-operation here in Manchester – our second city, I am prepared to concede.

- ↑ "'Setting the Standard' – Speech by Phil Woolas MP at the fifth Annual Assembly of Standards Committees on 16 October 2006.". Department for Communities and Local Government. Department for Communities and Local Government. 16 October 2006. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

And, of course, I, and colleagues in Manchester, am pleased to see its very sensible plans to relocate to Manchester – Britain's third city.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland". MSN Encarta – Northern Ireland. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ↑ "Census 2011". Birmingham City Council. 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 "2011 Census – Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ↑ "British urban pattern: population data" (PDF). ESPON project 1.4.3 Study on Urban Functions. European Union – European Spatial Planning Observation Network. March 2007. pp. 119–120. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ↑ Uglow, Jenny (2002). The Lunar Men – the friends who made the future. London: Faber & Faber. pp. xiii, 500–501. ISBN 0-571-21610-2.; Jones 2008, pp. 14, 19, 71, 82–83, 231–232

- ↑ Hopkins 1989, p. 26

- ↑ Berg 1991, pp. 174, 184; Jacobs, Jane (1969). The economy of cities. New York: Random House. pp. 86–89. OCLC 5585.

- ↑ Ward 2005, jacket; Briggs, Asa (1990) [1965]. Victorian Cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 185; 187–189. ISBN 0-14-013582-0.; Jenkins, Roy (2004). Twelve cities: a personal memoir. London: Pan Macmillan. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0-330-49333-7. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "The World According to GaWC 2010". Globalization and World Cities Research Network. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Hawksworth, John; Hoehn, Thomas; Tiwari, Anmol (2 November 2009). "Global city GDP rankings 2008–2025" (PDF). UK Economic Outlook November 2009. PricewaterhouseCoopers. p. 32. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ↑ "Table 0 – All students by institution, mode of study, level of study and domicile 2008/09". Higher education Statistics Agency. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ↑ Maddocks, Fiona (6 June 2010). "Andris Nelsons, magician of Birmingham". The Observer (Guardian News and Media). Retrieved 31 January 2011.; Craine, Debra (23 February 2010). "Birmingham Royal Ballet comes of age". The Times (Times Newspapers). Retrieved 31 January 2011.; "The Barber Institute of Fine Arts". Johansens. Condé Nast. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ↑ "Big City Plan Website". Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ↑ http://www.espon.eu/export/sites/default/Documents/Projects/ESPON2006Projects/StudiesScientificSupportProjects/UrbanFunctions/fr-1.4.3_April2007-final.pdf#page=119

- ↑ Williams, Sally (7 July 2010). "City's new look pulls in foreign tourists". South Wales Echo (Cardiff: Media Wales Ltd). Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ "Eurocities". Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ↑ "City of Edinburgh factsheet" (PDF). gro-scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ "Population and living conditions in Urban Audit cities, larger urban zone (LUZ)". Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "City of Literature". cityofliterature.com. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ "Edinburgh-World Heritage Site". VisitScotland. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Quality of life". Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Edinburgh second in TripAdvisor UK tourism poll". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ "Victorian Glasgow". BBC History. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ↑ "About Glasgow: The Second City of the Empire – the 19th century". Glasgow City Council. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ↑ Fraser, W. H. "Second City of The Empire: 1830s to 1914". University of Glasgow. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ McIlvanney, W. "Glasgow – city of reality". Scotland – the official online gateway. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ "About Glasgow: Factsheets". Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ↑ "Factsheet 4: Population" (PDF). Glasgow City Council. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ↑ "Visiting Glasgow: Clyde Bridges". Glasgow City Council. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ↑ "2007 Population Estimates" (PDF). Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ↑ "Minister backs SPT on White Paper". Interchange Issue 7. Strathclyde Partnership for Transport. September 2004. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "Office for National Statistics (ONS)". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Leeds Tourist Attractions, England". PlanetWare. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Leeds stakes its claim to be the financial hub". Yorkshire Post. 8 November 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "We're leading the way in finance world". Yorkshire Evening Post. 8 February 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Leeds is Booming". Leeds City Guide. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ http://www.leeds-city-guide.com/Body

- ↑ The North West of England Plan Regional Spatial Strategy to 2021 http://www.4nw.org.uk/downloads/documents/oct_08/nwra_1224233363_Final_adopted_RSS_300908_Liver.pdf

- ↑ https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32080/11-1338-rebalancing-britain-liverpool-city-region.pdf

- ↑ Ten facts about Liverpool Telegraph, 4 June 2003

- ↑ Hatton, Brian (2008). Shifted tideways: Liverpool's changing fortunes. The Architectural Review.

- ↑ Henderson, W.O. (1933). The Liverpool office in London. Economica xiii. London School of Economics. pp. 473–479.

- ↑ http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/d13decf6-3ac9-11df-b6d5-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2kv5Dr0vX

- ↑ "Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City". UK Local Authority World Heritage Forum. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ↑ Hughes (1999), p10

- ↑ Hughes (1999), p11

- ↑ "Grade I listing for synagogue". BBC. 3 March 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ "Listed buildings". Liverpool City Council. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ↑ "Historic Britain: Liverpool". HistoricBritain.com. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ↑ "Merseyside Facts". The Mersey Partnership. 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ↑ "Heritage map for changing city". BBC News. 19 March 2002. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ "People power to decide fate of new £5.5bn waterfront". Liverpool Echo. 7 March 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ↑ "City of Liverpool Cruise Terminal". Liverpool City Council. 10 December 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 "Birmingham overtakes Glasgow in top 10 most-visited" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ↑ "Top 150 City Destinations: London Leads the Way". Euromonitor International. 11 October 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ↑ "Host City: Liverpool". England 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ↑ "UK recession tour: Liverpool's retail therapy pays off". London: Daily Telegraph. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ↑ "2011 Census" (PDF). ONS (ONS). 16 July 2012

- ↑ The first of these to be included, Wythenshawe, was added to the city in 1931.

- ↑ Aspin, Chris (1981). The Cotton Industry. Shire Publications Ltd. p. 3. ISBN 0-85263-545-1.

- ↑ Kidd, Alan (2006). Manchester: A History. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 1-85936-128-5.

• Frangopulo, Nicholas (1977). Tradition in Action. The historical evolution of the Greater Manchester County. Wakefield: EP Publishing. ISBN 0-7158-1203-3.

• "Manchester – the first industrial city". Entry on Sciencemuseum website. Retrieved 17 March 2012. - ↑ Note: Manchester United's ground is in Greater Manchester but outside Manchester city limits; it is in the borough of Trafford.

- ↑ "National Statistics Online – International Visits" (PDF). ONS. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ↑ "Census 2011: Five lesser-spotted things in the data". BBC News. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ↑ "Census shows increase in population of the West Midlands". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 September 2012.