Scottish religion in the eighteenth century

Scottish religion in the eighteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the eighteenth century. This period saw the beginnings of a fragmentation of the Church of Scotland that had been created in the Reformation and established on a fully Presbyterian basis after the Glorious Revolution. These fractures were prompted by issues of government and patronage, but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party. The legal right of lay patrons to present clergymen of their choice to local ecclesiastical livings led to minor schisms from the church. The first in 1733, known as the First Secession and headed by figures including Ebenezer Erskine, led to the creation of a series of secessionist churches. The second in 1761 lead to the foundation of the independent Relief Church. In 1743 the Cameronians established themselves as the Reformed Presbyterian Church, remaining largely separate from religious and political debate. A number of minor sects developed, such as the Bereans, Buchanites, Daleites and Glassites.

Episcopalianism had retained supporters through the civil wars and changes of regime in the seventeenth century. Since most Episcopalians gave their support to the Jacobite rebellions in the first half of the early eighteenth century, they suffered a decline in fortunes. The remoteness of the Highlands and the lack of a Gaelic-speaking clergy undermined the missionary efforts of the established church. The later eighteenth century saw some success, owing to the efforts of the SSPCK missionaries and to the disruption of traditional society. Catholicism had been reduced to the fringes of the country, particularly the Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands. Conditions grew worse for Catholics after the Jacobite rebellions and Catholicism was reduced to little more than a poorly run mission. There was Evangelical Revival from the 1730s, reaching its peak at the Cambuslang Wark in 1742. The movement benefited the secessionist churches who gained recruits.

Church of Scotland

The religious settlement after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 adopted the legal forms of 1592, which instituted a fully Presbyterian settlement, and doctrine based on the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith.[1] The early eighteenth century saw the growth of "praying societies", who supplemented the services of the established kirk with communal devotions. These often had the approval of parish ministers and their members were generally drawn from the lower ranks of local society. Their outlook varied but they disliked preaching that simply emphasised the Law or that understood the gospel as a new law neonomianism, or that was mere morality, and sought out a gospel that stressed the Grace of God in the sense set out in the Confession of Faith. They were associated with the Marrow of Modern Divinity Controversy, a puritan book promoted by Thomas Boston and others and often disliked the role of lay patronage in the kirk.[2]

There were growing divisions between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party.[3] While Evangelicals emphasised the authority of the Bible and the traditions and historical documents of the kirk, the Moderates tended to stress intellectualism in theology, the established hierarchy of the kirk and attempted to raise the social status of the clergy.[4] From the 1760s the Moderates gained an ascendancy in the General Assembly of the Church. They were led by the historian William Robertson, who became principal of the University of Edinburgh and then by his successor George Hill, who was professor at the University of Aberdeen.[4] Evangelical leaders included John Willison (1680-1750), John McLaurin (1693-1754), Alexander Webster (1707-84) and John Erskine (1721-1803), for 26 years a colleague to William Robertson, but it was Thomas Boston (1677-1732) who was among the most popular theological writers, judged by books printed in Scotland.[5]

Secession

The late eighteenth century saw the beginnings of a fragmentation of the Church of Scotland that had been created in the Reformation. These fractures were prompted by issues of government and patronage, but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party over fears of fanaticism by the former and the acceptance of Enlightenment ideas by the latter.[3] Ecclesiastical patronage, the right of local lairds or other notables to appoint ministers to a parish, had been abolished at the Glorious Revolution, but it was reintroduced in the Patronage Act of 1711, resulting in frequent protests from the Kirk. The first secession was over the right to appoint in cases where a patron made no effort to fill a vacancy. The result was that a group of four ministers, led by Ebenezer Erskine, the minister of Stirling, formed a distinct "Associate Presbytery" in 1733, but were not forced from the Kirk until 1740. This First Secession was initially very small, but was petitioned by the praying societies, with requests for preaching.[6] Although its founding ministers were from Perthshire and Fife, the forty congregations they had established by 1740 were widely spread across the country, mainly among the middle classes of major towns. The Secessionists soon split amongst themselves over the issue of the burgess oath, which was administered after the 1745 rebellion as an anti-Jacobite measure, but which implied that the Church of Scotland was the only true church. The "burghers", led by Erskine, maintained that the oath could be taken, but they were excommunicated by an "anti-burgher" faction, led by Andrew Gibb, who established a separate General Associate Synod.[7] In the 1790s the Seceders became embroiled in the Old and New Light controversy. The "Old Lichts" continued to follow the principles of the Covenanters, while the "New Lichts" were more focused on personal salvation and considered the strictures of the Covenants as less binding and that a connection of the church and the state was not warranted.[8]

The second break from the Kirk was also prompted by issues of patronage. Minister Thomas Gillespie was deposed by the General Assembly in 1752 after he refused to participate in inducting a minister to the Inverkeithing parish, since the parishioners opposed the appointment. Gillespie was joined by two other ministers and they held the first meeting of the Presbytery of Relief at Colinsburgh in Fife in 1761.[7] While evangelical in doctrine, the Relief Church did not maintain that it was the only true church, but that it was still in communion with the kirk and maintained contact with Episcopalians and Independents.[8] Like the Associate Presbytery the movement benefited from the Evangelical Revival of the later eighteenth century.[9]

Episcopalianism

Episcopalianism had retained supporters through the civil wars and changes of regime in the seventeenth century. Although the bishops had been abolished in the settlement that followed the Glorious Revolution, becoming "non-jurors", not subscribing to the right of William and Mary to be monarchs, they continued to consecrate Episcopalian clergy. Many clergy were "outed" from their livings, but the king had issued two acts of indulgence in 1693 and 1695, allowing those who accepted him as king to retain their livings and around a hundred took advantage of the offer.[10] New "meeting houses" sprang up for those who continued to follow the episcopalian clergy. They generally prospered under Queen Anne[1] and all but the hardened Jacobites would be given toleration in 1712.[10] Since most Episcopalians gave their support to the Jacobite rebellion in 1715, they suffered a decline in fortunes.[3] A number of the clergy were deprived and in 1719 all meeting houses where prayers were not offered for King George were closed. In 1720 the last surviving bishop died and another was appointed as "primus", without any particular episcopal see. After the Jacobite rising of 1745, there was another round of restrictions under the Toleration Act of 1746 and Penal Act of 1748, and the number of clergy and congregations declined. The church was sustained by the important nobles and gentlemen in its ranks.[1]

This period saw the establishment of Qualified Chapels, where worship was conducted according to the English Book of Common Prayer and where congregations, led by priests ordained by Bishops of the Church of England or the Church of Ireland, were willing to pray for the Hanoverians.[11] Such chapels drew their congregations from English people living in Scotland and from Scottish Episcopalians who were not bound to the Jacobite cause. These two forms of episcopalianism existed side by side until 1788 when the Jacobite claimant Charles Edward Stuart died in exile. Unwilling to recognise his brother Henry Benedict Stuart, who was a cardinal in the Roman Catholic Church, as his heir, the non-juror Episcopalians elected to recognise the House of Hanover and offer allegiance to George III. At the repeal of the penal laws in 1792 there were twenty-four Qualified Chapels in Scotland.[12]

Cameronians

The Society People, known after one of their leaders as the Cameronians, who had not accepted the restoration of episcopacy in 1660, remained outside of the established kirk after the Revolution settlement. After years of persecution their numbers were few and largely confined to the south-west of the country. Their last remaining ministers re-entered the Church of Scotland at the Revolution, but the membership refused to accept an "un-Covenanted" kirk.[1] Having obtained the services of two ministers, in 1743 they established themselves as the Reformed Presbyterian Church. They remained separate from other denominations and abstained from political involvement, refusing even to vote.[1]

Minor sects

As well as the series of secessionist movements, the eighteenth century saw the formation of a number of minor sects. These included the Glasites, formed by Church of Scotland minister John Glas, who was expelled from his parish of Tealing in 1730 for his objections to the state's intervention in the affairs of the kirk. He advocated a strong form of biblical literalism. With his son-in-law Robert Sandeman, from whose name they are known as the Sandemanians, he founded a number of churches in Scotland and the sect expanded to England and the United States.[13] Closely involved with the Glasites were the followers of industrialist David Dale who broke with the kirk in the 1760s and formed the Old Scotch Independents, sometimes known as the Daleists. He preached a combination of industry and faith that led him to co-found the cotton-mill at New Lanark and to contribute to the Utopian Socialism associated with his son-in-law Robert Owen.[14] The Bereans were formed by John Barclay in Edinburgh in 1773. Barclay was one of the most prominent followers of moral philosopher Archibald Campbell and espoused a rigorous form of pre-destination and insisted on Biblical-based preaching. Having been rejected from various pastorships and by the General Assembly, he founded independent churches in Scotland and then in England, taking the name Bereans from the people mentioned in Acts 17:11. After Barclay's death in 1798 his followers joined the congregationalists.[15] The Buchanites were a Millenarian cult that broke away from the Relief Church when Hugh White, minister at Irvine, declared Elspeth Buchan to be a special saint identified with the woman described in Revelation 12. They attracted less than fifty followers and having been expelled by local magistrates they formed a community at a farm known as New Cample in Nithsdale, Dumfriesshire. The sect collapsed after the death of Buchan in 1791.[16]

Catholicism

Catholicism had been reduced to the fringes of the country, particularly the Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands. Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation had deteriorated.[3] The Pope appointed Thomas Nicolson as the first Vicar Apostolic over the mission in 1694.[17] The country was organised into districts and by 1703 there were thirty-three Catholic clergy. Conditions grew worse for Catholics after the Jacobite rebellions and Catholicism was reduced to little more than a poorly run mission.[3] In 1733 it was divided into two vicariates, one for the Highland and one for the Lowland, each under a bishop. There were six attempts to found a seminary in the Highlands between 1732 and 1838, all of which floundered on financial issues.[17] Clergy entered the country secretly and although services were illegal they were maintained. In 1755 it was estimated that there were only 16,500 communicants, mainly in the north and west, although the number is probably an underestimate.[1] By the end of the century this had probably fallen by a quarter due to emigration.[17] The First Relief Act of 1778, was designed to bring a measure of toleration to Catholics, but the resulting anti-Catholic riots in Scotland, meant that it was limited to England.[18] The provisions of the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, which allowed freedom of worship for Catholics who took an oath of allegiance, were extended to Scotland in 1793.[19] In 1799 the Lowland District seminary was transferred to Aquhorthies, near Inverurie in Aberdeenshire, so that it could serve the entire country. It was secretly funded by the government, who were concerned at the scale of emigration by Highland Catholics.[17]

Missions

Long after the triumph of the Church of Scotland in the Lowlands, Highlanders and Islanders clung to a form of Christianity infused with animistic folk beliefs and practices. The remoteness of the region and the lack of a Gaelic-speaking clergy undermined missionary efforts. The Scottish Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SSPCK) was founded by Royal Charter in 1708. Its aim was partly religious and partly cultural, intending to "wear out" Gaelic and "learn the people the English tongue". By 1715 it was running 25 schools, by 1755 it was 116 and by 1792 it was 149, but most were on the edges of the Highlands. The difficulty of promoting Protestantism and English in a Gaelic speaking region, eventually led to a change of policy in the SSPCK and in 1754 it sanctioned the printing of a Bible with Gaelic and English text on facing pages. The government only began to seriously promote Protestantism from 1725, when it began to make a grant to the General Assembly known as the Royal Bounty. Part of this went towards itinerant ministers, but by 1764 there were only ten. Probably more significant for the spread of Protestantism were the lay catechists, who met the people on the Sabbath, read Scripture, and joined them in Psalms and prayers. They would later be important in the Evangelical revival.[20]

Evangelical Revival

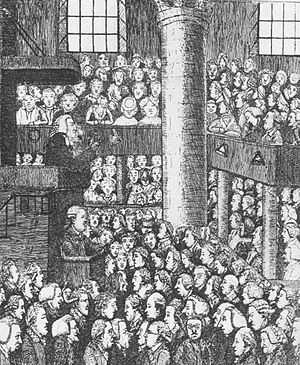

From the later 1730s Scotland experienced a version of the Evangelical Revival that affected England and Wales and North America, in which Protestant congregations, usually in a specific locations, experienced intense "awakenings" of enthusiasm, renewed commitment and, sometimes, rapid expansion. This was first seen at Easter Ross in the Highlands in 1739 and most famously in the Cambuslang Wark near Glasgow in 1742,[20] where intense religious activity cumulated in a crowd of perhaps 30,000 gathering there to hear English preacher George Whitefield.[21] Scotland was also visited 22 times by John Wesley, the English evangelist and founder of Methodism, between 1751 and 1790.[22]

Most of the new converts were relatively young and from the lower groups in society, such as small tenants, craftsmen, servants and the unskilled, with a relatively high proportion of unmarried women. This has been seen as a reaction against the oligarchical nature of the established kirk, which was dominated by local lairds and heritors. Unlike awakenings elsewhere, the revival in Scotland did not give rise to a major religious movement, but benefited the secession churches.[23] The revival was particularly significant in the Highlands, where the lack of a clear parochial structure led to a pattern of spiritual enthusiasm, recession and renewal, often instigated by lay catechists, known as "the Men", who would occasionally emerge as charismatic leaders. The revival left a legacy of strict Sabbatarianism and local identity.[17]

In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, Scotland gained many of the organisations associated with the revival in England, including Sunday Schools, mission schools, ragged schools, Bible societies and improvement classes.[24] Because the revival occurred at the same time as the transformation of the Highlands into a crofting society, Evangelicalism was often linked to popular protest against patronage and the clearances, while the Moderates became identified with the interests of the landholding classes. It laid the ground for the Great Disruption in the mid-nineteenth century, leading to the Evangelicals taking control of the General Assembly and those in the Highlands joining the Free Church of Scotland in large numbers.[17]

The leading figure in the Evangelical movement within the Church of Scotland in the eighteenth century was John Erskine (1721–1803), who was minister of Old Greyfriars Church in Edinburgh from 1768. He was orthodox in doctrine, but sympathised with the Enlightenment and supported reforms in religious practice. A popular preacher, he corresponded with religious leaders in other countries, including New England theologian Johnathan Edwards (1703–58), whose ideas were a major influence on the movement in Scotland.[25]

Religion and society

The kirk had considerable control over the lives of the people. It had a major role in the Poor Law and schools, which were administered through the parishes, and over the morals of the population, particularly over sexual offences such as adultery and fornication. A rebuke was necessary for moral offenders to "purge their scandal". This involved standing or sitting before the congregation for up to three Sundays and enduring a rant by the minister. There was sometimes a special repentance stool near the pulpit for this purpose. In a few places the subject was expected to wear sackcloth. From the 1770s private rebukes were increasingly administered by the kirk session, particularly for men from the social elites, while until the 1820s the poor were almost always give a public rebuke.[26] In the early part of the century the kirk, particularly in the Lowlands, attempted to suppress dancing and events like penny weddings at which secular tunes were played.[27] The oppression of secular music and dancing by the kirk began to ease between about 1715 and 1725.[28]

In Presbyterian worship the sermon was seen as central, meaning that services tended to have a didactic and wordy character. The only participation by the congregation was musical, in the singing of the psalms.[29] From the late seventeenth century the common practice was lining out, by which the precentor sang or read out each line and it was then repeated by the congregation. From the second quarter of the eighteenth century it was argued that this should be abandoned in favour of the practice of singing stanza by stanza.[30] In the second half of the century these innovations became linked to a choir movement that included the setting up of schools to teach new tunes and singing in four parts.[31]

Among Episcopalians, Qualified Chapels used the English Book of Common Prayer. They installed organs and hired musicians, following the practice in English parish churches, singing in the liturgy as well as metrical psalms, while the non-jurors had to worship covertly and less elaborately. When the two branches united in the 1790s, the non-juring branch soon absorbed the musical and liturgical traditions of the qualified churches.[32]

Communion was the central occasion of the church, conducted infrequently, at most once a year. Communicants were examined by a minister and elders, proving their knowledge of the Shorter Catechism. They were then given communion tokens that entitled them to take part in the ceremony. Long tables were set up in the middle of the church at which communicants sat to receive communion. Where ministers refused or neglected parish communion, largely assemblies were carried out in the open air, often combining several parishes. These large gatherings were discouraged by the General Assembly, but continued. They could become mixed with secular activities and were commemorated as such by Robert Burns in the poem Holy Fair. They could also be occasions for evangelical meetings, as at the Cambuslang Wark.[29]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 298–9.

- ↑ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 300.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5 (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 303-4.

- ↑ J. Yeager, Enlightened Evangelicalism: The Life and Thought of John Erskine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 49-50.

- ↑ M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, p. 399.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 302.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, p. 400.

- ↑ G. M. Ditchfield, The Evangelical Revival (London: Routledge, 1998), ISBN 185728481X, p. 91.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 252–3.

- ↑ N. Yates, Eighteenth-Century Britain: Religion and Politics 1714–1815 (London: Pearson Education, 2008), ISBN 1405801611, p. 49.

- ↑ D. Bertie, ed., Scottish Episcopal Clergy, 1689–2000, p. 649.

- ↑ L. Cohn-Sherbok, Who's Who in Christianity (London: Taylor & Francis, 2013), ISBN 1134778937, p. 107.

- ↑ J. Wormald, Scotland : A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), ISBN 0191622435.

- ↑ W. H. Brackney, Historical Dictionary of Radical Christianity (Plymouth: Scarecrow Press, 2012), ISBN 0810873656, p. 52.

- ↑ J. F. C. Harrison, The Second Coming: Popular Millenarianism 1780–1850 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1979), ISBN 0710001916, p. 33.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, p. 365.

- ↑ J. Black, The Politics of Britain: 1688-1800 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993), ISBN 0719037611, p. 61.

- ↑ T. Gallagher, Glasgow: The Uneasy Peace : Religious Tension in Modern Scotland, 1819–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), ISBN 0719023963, p. 9.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, p. 364.

- ↑ D. Bebbington, Victorian Religious Revivals: Culture and Piety in Local and Global Contexts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199575487, p. 5.

- ↑ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 304.

- ↑ G. M. Ditchfield, The Evangelical Revival (London: Routledge, 1998), ISBN 185728481X, pp. 53 and 91.

- ↑ M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, p. 403.

- ↑ D. W. Bebbington, "Religious life: 6 Evangelism" in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 515-16.

- ↑ C. G. Brown, Religion and Society in Scotland Since 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997), ISBN 0748608869, p. 72.

- ↑ J. Porter, "Introduction" in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007), ISBN 3-03910-948-0, p. 22.

- ↑ M. Gardiner,Modern Scottish Culture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), ISBN 978-0748620272, pp. 193–4.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 D. Murray, "Religious life: 1650–1750" in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 513–4.

- ↑ B. D. Spinks, A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0810869810, pp. 143–4.

- ↑ B. D. Spinks, A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0810869810, p. 26.

- ↑ R. M. Wilson, Anglican Chant and Chanting in England, Scotland, and America, 1660 to 1820 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), ISBN 0198164246, p. 192.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||