Scottish people

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 28–40 million worldwideA[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

6,006,955 Scottish 5,393,554 Scotch-Irish[3][4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,719,850[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,792,600[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 795,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 760,620[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 80,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12,792[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2,403[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,459[9][10] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

English (Scottish English) Scottish Gaelic • Scots | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Presbyterianism, Roman Catholicism, Episcopalianism; other minority groups; agnostics, deists and atheists. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A These figures are estimates based on official | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

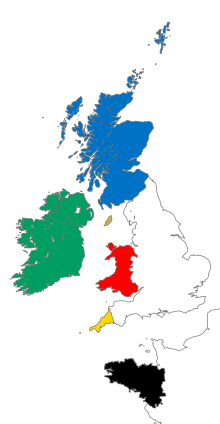

The Scottish people (Scots: Scots Fowk, Scottish Gaelic: Albannaich), or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically, they emerged from an amalgamation of two Celtic peoples—the Picts and Gaels—who founded the Kingdom of Scotland (or Alba) in the 9th century. Later, the neighbouring Cumbrian Celts, as well as Germanic Anglo-Saxons and Norse, were incorporated into the Scottish nation.

In modern use, "Scottish people" or "Scots" is used to refer to anyone whose linguistic, cultural, family ancestral or genetic origins are from within Scotland. The Latin word Scotti[15] originally referred to the Gaels but came to describe all inhabitants of Scotland.[16] Though sometimes considered archaic or pejorative,[17] the term Scotch has also been used for the Scottish people, though this usage is current primarily outside Scotland.[18][19]

There are people of Scottish descent in many countries other than Scotland. Emigration, influenced by factors such as the Highland and Lowland Clearances, Scottish participation in the British Empire, and latterly industrial decline and unemployment, resulted in Scottish people being found throughout the world. Large populations of Scottish people settled the new-world lands of North and South America, Australia and New Zealand. There is a Scottish presence at a particularly high level in Canada, which has the highest level per-capita of Scots descendants in the world and second largest population of descended Scots ancestry, after the United States. They took with them their Scottish languages and culture.[20]

Scotland has seen migration and settlement of peoples at different periods in its history. The Gaels, the Picts and the Britons had respective origin myths, like most Middle Ages European peoples.[21] Germanic peoples, such as the Anglo-Saxons, arrived beginning in the 7th century, while the Norse settled many regions of Scotland from the 8th century onwards. In the High Middle Ages, from the reign of David I of Scotland, there was some emigration from France, England and the Low Countries to Scotland. Some famous Scottish family names, including those bearing the names which became Bruce, Balliol, Murray and Stewart came to Scotland at this time. Today Scotland is one of the countries of the United Kingdom and the majority of people living in Scotland are British citizens.

Ethnic groups of Scotland

In the Early Middle Ages, Scotland had several ethnic or cultural groups labelled as such in contemporary sources, namely the Picts, the Gaels, the Britons, with the Angles settling in the southeast of the country. Culturally, these peoples are grouped according to language. Most of Scotland until the 13th century spoke Celtic languages and these included, at least initially, the Britons, as well as the Gaels and the Picts.[22] Germanic peoples included the Angles of Northumbria, who settled in south-eastern Scotland in the region between the Firth of Forth to the north and the River Tweed to the south. They also occupied the south-west of Scotland up to and including the Plain of Kyle and their language, Old English, was the earliest form of the language which eventually became known as Scots. Later the Norse arrived in the north and west in quite significant numbers, recently discovered to have left about thirty percent of men in the Outer Hebrides with a distinct, Norse marker in their DNA.

Use of the Gaelic language spread throughout nearly the whole of Scotland by the 9th century,[23] reaching a peak in the 11th to 13th centuries, but was never the language of the south-east of the country.[23]

After the division of Northumbria between Scotland and England by King Edgar (or after the later Battle of Carham; it is uncertain, but most medieval historians now accept the earlier 'gift' by Edgar) the Scottish kingdom encompassed a great number of English people, with larger numbers quite possibly arriving after the Norman invasion of England (Contemporary populations cannot be estimated so we cannot tell which population thenceforth formed the majority). South-east of the Firth of Forth then in Lothian and the Borders (OE: Loðene), a northern variety of Old English, also known as Early Scots, was spoken.

As a result of David I, King of Scots' return from exile in England in 1113, ultimately to assume the throne in 1124 with the help of Norman military force, David invited Norman families from France and England to settle in lands he granted them to spread a ruling class loyal to him.[24] This Davidian Revolution as many historians call it, brought a European style of Feudalism to Scotland along with an influx of people of Norman descent - unlike England where it was by conquest; by invitation. To this day, many of the common family names of Scotland can trace ancestry to Normans from this period, such as the Stewarts, the Bruces, the Hamiltons, the Wallaces, the Melvilles, some Browns and many others.

The Northern Isles and some parts of Caithness were Norn-speaking (the west of Caithness was Gaelic-speaking into the 20th Century, as were some small communities in parts of the Central Highlands). From 1200 to 1500 the Early Scots language spread across the lowland parts of Scotland between Galloway and the Highland line, being used by Barbour in his historical epic, 'The Brus' in the late 1300s in Aberdeen.

From 1500 until recent years, Scotland was commonly divided by language into two groups of people, Gaelic-speaking (formerly called Scottis by English speakers and known by many Lowlanders in the eighteenth century as 'Irish') "Highlanders" and the Inglis-speaking, later to be called, Scots-speaking, and later still, English-speaking "Lowlanders". Today, immigrants have brought other languages, but almost every adult throughout Scotland is fluent in the English language.

Scottish ancestry abroad

Today, Scotland has a population of just over five million people,[25] the majority of whom consider themselves Scottish.[26][27] In addition, there are many more people with Scots ancestry living abroad than the total population of Scotland. In the 2000 Census, 4.8 million Americans reported Scottish ancestry,[28] 1.7% of the total US population. A quarter of a million Ulster Scots emigrated to North America between 1717 and 1775.[29]

In Canada, according to the 2001 Census of Canada data, the Scottish-Canadian community accounts for 4,719,850 people.[3] Scottish-Canadians are the 3rd biggest ethnic group in Canada. Scottish culture has particularly thrived in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia (Latin for "New Scotland"). There, in Cape Breton, where both Lowland and Highland Scots settled in large numbers, Canadian Gaelic is still spoken by a small number of residents. Cape Breton is the home of the Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts. Glengarry County in present-day Eastern Ontario is a historic county that was set up as a settlement for Highland Scots, where many from the Highlands settled to preserve their culture in result of the Highland Clearances. Gaelic was the native language of the community since its settlement in the 18th century although the number of speakers decreased since as a result of English migration. As of the modern 21st century, there are still a few Gaelic speakers in the community.

Large numbers of Scottish people reside in other parts of the United Kingdom and in the Republic of Ireland, particularly Ulster where they form the Ulster-Scots community. The number of people of Scottish descent in England and Wales is impossible to quantify due to the ancient and complex pattern of migration within Great Britain. Of the present generation alone, some 800,000 people born in Scotland now reside in either England, Wales or Northern Ireland.[30]

Other European countries have had their share of Scots immigrants. The Scots have been emigrating to mainland Europe for centuries as merchants and soldiers.[31] Many emigrated to France, Poland,[32] Italy, Germany, Scandinavia,[33] and the Netherlands.[34] Recently some scholars suggested that up to 250,000 Russians may have Scottish blood.[35]

Significant numbers of Scottish people also settled in Australia and New Zealand. Approximately 20 percent of the original European settler population of New Zealand came from Scotland, and Scottish influence is still visible around the country.[36] The South Island city of Dunedin, in particular, is known for its Scottish heritage and was named as a tribute to Edinburgh by the city's Scottish founders. In Australia, the Scottish population was fairly evenly distributed around the country.

The largest population of Scots in Latin America is found in Argentina,[37] followed by Chile,[38] Brazil and Mexico.

Scots in continental Europe

Netherlands

It is said that the first people from the Low Countries to settle in Scotland came in the wake of Maud's marriage to the Scottish king, David I, during the Middle Ages. Craftsmen and tradesmen followed courtiers and in later centuries a brisk trade grew up between the two nations: Scotland's primary goods (wool, hides, salmon and then coal) in exchange for the luxuries obtainable in the Netherlands, one of the major hubs of European trade.

By 1600, trading colonies had grown up on either side of the well-travelled shipping routes: the Dutch settling along the eastern seaboard of Scotland; the Scots congregating first in Campvere – where they were allowed to land their goods duty-free and run their own affairs – and then Rotterdam, where Scottish and Dutch Calvinism coexisted comfortably. Besides the thousands (or the estimated over 1 million) of local descendants with Scots ancestry, both ports still show signs of these early alliances. Now a museum, 'The Scots House' in the town of Veere was the only place outwith Scotland where Scots Law was practised. In Rotterdam, meanwhile, the doors of the Scots International Church have remained open ever since 1643.[39]

Russia

The first Scots to be mentioned in Russia's history were the Scottish soldiers in Muscovy referred to as early as in the 14th century.[40] Among the 'soldiers of fortune' was the ancestor to famous Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov, called George Learmonth. A number of Scots gained wealth and fame in the times of Peter the Great and Catherine the Great.[41] These include Patrick Gordon, Samuel Greig, Charles Baird, Charles Cameron, Adam Menelaws, William Hastie. Several doctors to the Russian court were from Scotland,[42] the best known being James Wylie.

The next wave of migration established commercial links with Russia.[43]

The 19th century witnessed the immense literary cross-references between Scotland and Russia.

A Russian scholar, Maria Koroleva, distinguishes between 'the Russian Scots' (properly assimilated) and 'Scots in Russia', who remained thoroughly Scottish.[44]

There are several societies in contemporary Russia to unite the Scots. The Russian census lists does not distinguish Scots from other British people, so it is hard to establish reliable figures for the number of Scots living and working in modern Russia.

Poland

From as far back as the mid-16th century there were Scots trading and settling in Poland. A "Scotch Pedlar's Pack in Poland" became a proverbial expression. It usually consisted of cloths, woollen goods and linen kerchiefs (head coverings). Itinerants also sold tin utensils and ironware such as scissors and knives. Along with the protection offered by King Stephen in the Royal Grant of 1576 a district in Kraków was assigned to Scots immigrants.

Records from 1592 reveal Scots settlers, giving their employment as trader or merchant, being granted citizenship of Kraków. Payment for being granted citizenship ranged from 12 Polish florins to a musket and gunpowder, or an undertaking to marry within a year and a day of acquiring a holding.

By the 17th century, there were an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Scots living in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[33] Many came from Dundee and Aberdeen and could be found in Polish towns on the banks of the Vistula as far south as Kraków. Settlers from Aberdeenshire were mainly Episcopalians or Catholics, but there were also large numbers of Calvinists. As well as Scottish traders, there were also many Scottish soldiers in Poland. In 1656 a number of Scottish Highlanders who were disenchanted with Oliver Cromwell's rule went to Poland in the service of the King of Sweden.

The Scots integrated well and many acquired great wealth. They contributed to many charitable institutions in the host country, but did not forget their homeland; for example, in 1701 when collections were made for the restoration fund of the Marischal College, Aberdeen, the Scottish settlers in Poland gave generously.

Many Royal grants and privileges were granted to Scottish merchants until the 18th century, at which time the settlers began to merge more and more into the native population. "Bonnie Prince Charlie" was half Polish, being the son of James Stuart, the "Old Pretender", and Clementina Sobieska, granddaughter of Jan Sobieski, King of Poland.[45][46][47] In 1691, the City of Warsaw elected the Scottish immigrant Aleksander Czamer (Alexander Chalmers) as its mayor.[48]

Italy

By 1592, the Scottish community in Rome was big enough to merit the building of Sant'Andrea degli Scozzesi (English: St Andrew of the Scots). It was constructed for the Scottish expatriate community in Rome especially for those intended for priesthood. The adjoining hospice was a shelter for Catholic Scots who fled their country because of religious persecution. In 1615 Pope Paul V gave the hospice and the nearby Scottish Seminar to the Jesuits. It was rebuilt in 1645. The church and facilities became more important when James Francis Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender set his residence in Rome in 1717, but were abandoned during the French occupation of Rome in the late 18th century. In 1820, although religious activity was resumed, it was no longer led by the Jesuits. Sant'Andrea degli Scozzesi was reconstructed in 1869 by Luigi Poletti. The church was deconsecrated in 1962 and incorporated into a bank (Cassa di Risparmio delle Province Lombarde). The Scottish Seminar also moved away. The Feast of St Andrew is still celebrated there on 30 November.

Gurro in Italy is said to be populated by the descendants of Scottish soldiers. According to local legend, Scottish soldiers fleeing the Battle of Pavia who arrived in the area were stopped by severe blizzards that forced many, if not all, to give up their travels and settle in the town. To this day, the town of Gurro is still proud of its Scottish links. Many of the residents claim that their surnames are Italian translations of Scottish surnames. The town also has a Scottish museum.[49][50]

Culture

Language

Historically, Scottish people have spoken many different languages and dialects. The Pictish language, Norse, Norman-French and Brythonic languages have been spoken by forebears of Scottish people. However, none of these are in use today. The remaining three major languages of the Scottish people are English, Lowland Scots (various dialects) and Gaelic. Of these three, English is the most common form as a first language. There are some other minority languages of the Scottish people, such as Spanish, used by the population of Scots in Argentina.

The Norn language was spoken in the Northern Isles into the early modern period – the current dialects of Shetlandic and Orcadian are heavily influenced by it, to this day.

There is still debate whether Scots is a dialect or a language in its own right, as there is no clear line to define the two. Scots is usually regarded as a mid way between the two, as it is highly mutually intelligible with English, particularly the dialects spoken in the North of England as well as those spoken in Scotland, but is treated as a language in some laws.

Scottish English

After the Union of Crowns in 1603, the Scottish Court moved with James VI & I to London and English vocabulary began to be used by the Scottish upper classes.[51] With the introduction of the printing press, spellings became standardised. Scottish English, a Scottish variation of southern English English, began to replace the Scots language. Scottish English soon became the dominant language. By the end of the 17th century, Scots Language had practically ceased to exist, at least in literary form.[52] While Scots remained a common spoken language, the southern Scottish English dialect was the preferred language for publications from the 18th century to the present day. Today most Scottish people speak Scottish English, which has some distinctive vocabulary and may be influenced to varying degrees by Scots language.

Scots language

Lowland Scots, also known as Lallans or Doric, is a language of Germanic origin. It has its roots in Northern Middle English. After the wars of independence, the English used by Lowland Scots speakers evolved in a different direction from that of Modern English. Since 1424, this language, known to its speakers as Inglis, was used by the Scottish Parliament in its statutes.[51] By the middle of the 15th century, the language's name had changed from Inglis to Scottis. The reformation, from 1560 onwards, saw the beginning of a decline in the use of Scots forms. With the establishment of the Protestant Presbyterian religion, and lacking a Scots translation of the Bible, they used the Geneva Edition.[53] From that point on, God spoke English, not Scots.[54] Scots continued to be used in official legal and court documents throughout the 18th century. However, due to the adoption of the southern standard by officialdom and the Education system the use of written Scots declined. Lowland Scots is still a popular spoken language with over 1.5 million Scots speakers in Scotland.[55] The Scots language is used by about 30,000 Ulster Scots[56] and is known in official circles as Ullans. In 1993, Ulster Scots was recognised, along with Scots, as a variety of the Scots language by the European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages.[57]

Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language with similarities to Irish. Scottish Gaelic comes from Old Irish. It was originally spoken by the Gaels of Dál Riata and the Rhinns of Galloway, later being adopted by the Pictish people of central and eastern Scotland. Gaelic (lingua Scottica, Scottis) became the de facto language of the whole Kingdom of Alba, giving its name to the country (Scotia, "Scotland"). Meanwhile, Gaelic independently spread from Galloway into Dumfriesshire (it is unclear if the Gaelic of 12th century Clydesdale and Selkirkshire came from Galloway or Scotland-proper). The predominance of Gaelic began to decline in the 13th century, and by the end of the Middle Ages Scotland was divided into two linguistic zones, the English/Scots-speaking Lowlands and the Gaelic-speaking Highlands and Galloway. Gaelic continued to be spoken widely throughout the Highlands until the 19th century. The Highland clearances and the Education Act of 1872, which actively discouraged the use of Gaelic in schools, caused the numbers of Gaelic speakers to fall.[58] Many Gaelic speakers emigrated to countries such as Canada or moved to the industrial cities of lowland Scotland. Communities where the language is still spoken natively are restricted to the west coast of Scotland; and especially the Hebrides. However, large proportions of Gaelic speakers also live in the cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh in Scotland. A report in 2005 by the Registrar General for Scotland based on the 2001 UK Census showed about 92,400 people or 1.9% of the population can speak Gaelic while the number of people able to read and write rose by 7.5% and 10% respectively.[59] Outwith Scotland, there are communities of Scottish Gaelic speakers such as the Canadian Gaelic community; though their numbers have also been declining rapidly. The Gaelic language is recognised as a Minority Language by the European Union. The Scottish parliament is also seeking to increase the use of Gaelic in Scotland through the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005. Gaelic is now used as a first language in some Schools and is prominently seen in use on dual language road signs throughout the Gaelic speaking parts of Scotland. It is recognised as an official language of Scotland with "equal respect" to English.

Religion

The modern people of Scotland remain a mix of different religions. The Protestant and Catholic divisions still remain in the society. In Scotland the main Protestant body is the Church of Scotland which is Presbyterian. The high kirk for Presbyterians is St Giles' Cathedral. In the United States, people of Scottish and Scots-Irish descent are chiefly Protestant, with many belonging to the Baptist or Methodist churches, or various Presbyterian denominations.

Literature

Folklore

Science and engineering

John Logie Baird FRSE (14 August 1888 – 14 June 1946) was a Scottish scientist, engineer, innovator and inventor of the world's first television;[2] the first publicly demonstrated colour television system; and the first purely electronic colour television picture tube. Baird's early technological successes and his role in the practical introduction of broadcast television for home entertainment have earned him a prominent place in television's history.

Music

Sport

The modern games of curling and golf originated in Scotland. Both sports are governed by bodies headquartered in Scotland, the World Curling Federation and the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews respectively. Scots helped to popularise and spread the sport of association football; the first official international match was played in Glasgow between Scotland and England in 1872.

Cuisine

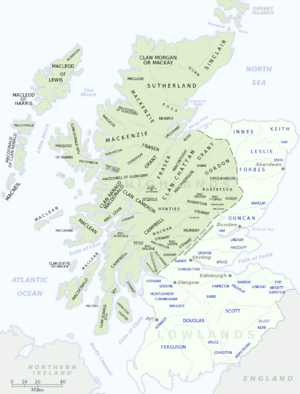

Clans

Anglicisation

Many Scottish surnames have become anglicised over the centuries. This reflected the gradual spread of English, also known as Early Scots, from around the 13th century onwards, through Scotland beyond its traditional area in the Lothians. It also reflected some deliberate political attempts to promote the English language in the outlying regions of Scotland, including following the Union of the Crowns under King James VI of Scotland and I of England in 1603, and then the Act of Union of 1707 and the subsequent defeat of rebellions.

However, many Scottish surnames have remained predominantly Gaelic albeit written according to English orthographic practice (as with Irish surnames). Thus MacAoidh in Gaelic is Mackay in English, and MacGill-Eain in Gaelic is MacLean and so on. Mac (sometimes Mc) is common as, effectively, it means "son of". MacDonald, MacAulay, Gilmore, Gilmour, MacKinley, Macintosh, MacKenzie, MacNeill, MacPherson, MacLear, MacAra, Craig, Lauder, Menzies, Galloway and Duncan are just a few of many examples of traditional Scottish surnames. There are, of course, also the many surnames, like Wallace and Morton, stemming from parts of Scotland which were settled by peoples other than the (Gaelic) Scots. The most common surnames in Scotland are Smith and Brown,[60] which come from several origins each – e.g. Smith can be a translation of Mac a' Ghobhainn (thence also e.g. MacGowan), and Brown can refer to the colour, or be akin to MacBrayne.

Anglicisation is not restricted to language. In his Socialism: critical and constructive, published in 1921, future Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald wrote: "The Anglification of Scotland has been proceeding apace to the damage of its education, its music, its literature, its genius, and the generation that is growing up under this influence is uprooted from its past."[61]

Etymology

The word Scotia was used by the Romans, as early as the 1st century CE, as the name of one of the tribes in what is now Scotland. The Romans also used Scotia to refer to the Gaels living in Ireland.[62] The Venerable Bede (c. 672 or 673 – 27 May, 735) uses the word Scottorum for the nation from Ireland who settled part of the Pictish lands: "Scottorum nationem in Pictorum parte recipit." This we can infer to mean the arrival of the people, also known as the Gaels, in the Kingdom of Dál Riata, in the western edge of Scotland. It is of note that Bede used the word natio (nation) for the Scots, where he often refers to other peoples, such as the Picts, with the word gens (race).[63] In the 10th century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the word Scot is mentioned as a reference to the "Land of the Gaels". The word Scottorum was again used by an Irish king in 1005: Imperator Scottorum was the title given to Brian Bóruma by his notary, Mael Suthain, in the Book of Armagh.[64] This style was subsequently copied by the Scottish kings. Basileus Scottorum appears on the great seal of King Edgar (1074–1107).[65] Alexander I (c. 1078–1124) used the words Rex Scottorum on his great seal, as did many of his successors up to and including James VI.[66]

In modern times the words Scot and Scottish are applied mainly to inhabitants of Scotland. The possible ancient Irish connotations are largely forgotten. The language known as Ulster Scots, spoken in parts of northeastern Ireland, is the result of 17th and 18th century immigration to Ireland from Scotland.

In the English language, the word Scotch is a term to describe a thing from Scotland, such as Scotch whisky. However, when referring to people, the preferred term is Scots. Many Scottish people find the term Scotch to be offensive when applied to people.[67] The Oxford Dictionary describes Scotch as an old-fashioned term for "Scottish".[68]

See also

|

Notes

- ↑ "The Scottish Diaspora and Diaspora Strategy: Insights and Lessons from Ireland". Scottish Government. May 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Table 2: Ethnic Groups, Scotland, 2001 and 2011

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 American Community Survey 2008 by the US Census Bureau estimates 5,827,046 people claiming Scottish ancestry and 3,538,444 people claiming Scotch-Irish ancestry.

- ↑ Who are the Scots-Irish?

- ↑ "ABS Ancestry". 2012.

- ↑ Northern Ireland#Demography

- ↑ stats.govt.nz

- ↑ http://www.gov.im/lib/docs/treasury/economic/census/censusreport2006.pdf

- ↑ https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/274477/scotland_analysis_borders_citizenship.pdf#page=70

- ↑ http://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/285746/0087034.pdf#Page=13 http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2009/09/24095045/3

- ↑ Friends Of Scotland

- ↑ The Ancestral Scotland website states the following: "Scotland is a land of 5.1 million people. A proud people, passionate about their country and her rich, noble heritage. For every single Scot in their native land, there are thought to be at least five more overseas who can claim Scottish ancestry; that's many millions spread throughout the globe."

- ↑ History, Tradition and roots, ancestry

- ↑ Visit Scotland.org

- ↑ Bede used a Latin form of the word Scots as the name of the Gaels of Dál Riata.Roger Collins, Judith McClure; Beda el Venerable, Bede ({1999}). The Ecclesiastical History of the English People: The Greater Chronicle ; Bede's Letter to Egbert. Oxford University Press. p. 386. ISBN. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Anthony Richard (TRN) Birley, Cornelius Tacitus; Cayo Cornelio Tácito. Agricola and Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN.

- ↑ "Scotch". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ "Scotch: Definition, Synonyms from". Answers.com. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ John Kenneth Galbraith in his book The Scotch (Toronto: MacMillan, 1964) documents how the descendants of 19th century pioneers from Scotland who settled in Southwestern Ontario affectionately referred to themselves as Scotch. He states the book was meant to give a true picture of life in the Scotch-Canadian community in the early decades of the 20th century.

- ↑ Landsman, Ned C. (1 October 2001). Nation and Province in the First British Empire: Scotland and the Americas,. Bucknell University Press. ISBN.

- ↑ The Venerable Bede tells of the Scotti coming from Spain via Ireland and the Picts coming from Scythia. Harris, Stephen J. (1 October 2003). Race and Ethnicity in Anglo-Saxon Literature. Routledge (UK). p. 72. ISBN.

- ↑ Jackson, "The Language of the Picts", discussed by Forsyth, Language in Pictland.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1

- ↑ Barrow, "The Balance of New and Old", p. 13.

- ↑ Office of the Chief Statistician. "Analysis of Ethnicity in the 2001 Census – Summary Report".

- ↑ David McCrone, Professor of Sociology, University of Edinburgh. "Scottish Affairs, No. 24, Summer 1998; Opinion Polls in Scotland: July 1997 – June 1998". During 1997–1998 two polls were undertaken. During the first when asked about their national identity 59 percent of the people polled stated they were Scottish or more Scottish than British, 28 percent stated they were equally Scottish and British, while 10 percent stated they were British or more British than Scottish. In the second poll 59 percent of the people polled stated they were Scottish or more Scottish than British, 26 percent stated they were equally Scottish and British, while 12 percent stated they were British or more British than Scottish.

- ↑ The Scottish Government. "One Scotland Many Cultures 2005/06 – Waves 6 and 7 Campaign Evaluation".When asked what ethnic group they belonged over five surveys, in the 2005/2006 period, people reporting that they were Scottish rose from 75 percent to 84 percent, while those reporting that they were British dropped from 39 percent to 22 percent. "a number of respondents selected more than one option, usually both Scottish and British, hence percentages adding to more than 100% ... This indicates a continued erosion of perceived Britishness among respondents..."

- ↑ United States – QT-P13. Ancestry: 2000. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Summary File 3, Matrices PCT15 and PCT18.

- ↑ Thernstrom, Stephan (1980). Harvard encyclopedia of American ethnic groups. Harvard University Press. p. 896. ISBN 0-674-37512-2.

- ↑ "UK | Scotland". BBC News. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ See David Armitage, "The Scottish Diaspora", particularly pp. 272–278, in Jenny Wormald (ed.), Scotland: A History. Oxford UP, Oxford, 2005. ISBN

- ↑ "Scotland.org | The Official Gateway to Scotland". Friendsofscotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Eric Richards (2004). "Britannia's children: emigration from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland". Continuum International Publishing Group. p.53. ISBN 1-85285-441-3

- ↑ "History – Scottish History". BBC. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ url=http://scotlandonsunday.scotsman.com/index.cfm?id=1561162007 (30 September 2007). "Scot to bring DNA from Russia with Lermontov – Top stories". The Scotsman.

- ↑ Linguistic Archaeology: The Scottish Input to New Zealand English Phonology Trudgill et al. Journal of English Linguistics.2003; 31: 103–124

- ↑ "Scots in Argentina and Patagonia Austral". Electricscotland.com. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ "Archibald Cochrane". Electricscotland.com. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ "Scotland and The Netherlands, Trade, Business & Economy – Official Online Gateway to Scotland". Scotland.org. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ↑ Paul Dukes, Scottish soldiers in Moscovy in The Caledonian Phalanx, 1987

- ↑ A.G. Cross, Scoto-Russian contacts in the reign of Catherine the great (1762–1796), in The Caledonian Phalanx, 1987

- ↑ John H. Appleby, Through the looking-glass: Scottish doctors in Russia (1704–1854), in The Caledonian Phalanx, 1987

- ↑ John R. Bowles, From the banks of the Neva to the shores of Lake Baikal: some enterprising Scots in Russia, in The Caledonian Phalanx, 1987

- ↑ M.V. Koroleva, A.L. Sinitsa. Gelskoe naselenie Shotlandii, ot istokov k sovremennosti, in Demographic studies, Moscow, 2010, pp. 163–191.

- ↑ Polish Roots – Rosemary A. Chorzempa – Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ "Scotland and Poland". Scotland.org. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ↑ "Legacies – Immigration and Emigration – Scotland – North-East Scotland – Aberdeen's Baltic Adventure – Article Page 1". BBC. 5 October 2003. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ↑ "Warsaw | Warsaw's Scottish Mayor Remembered". Warsaw-life.com. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ↑ "strathspey Archive". Strathspey.org. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ↑ "Scottish Celts in Italy – Bonnie Prince Charlie in Bologna". Delicious Italy. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Crystal, David (25 August 2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN.

- ↑ Barber, Charles Laurence (1 August 2000). The English Language: A Historical Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 147. ISBN.

- ↑ MacMahon, April M. S.; McMahon (13 April 2000). Lexical Phonology and the History of English. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN.

- ↑ Murphy, Michael (EDT); Harry White (1 October 2001). Musical Constructions of Nationalism. Cork University Press. p. 216. ISBN.

- ↑ The General Register Office for Scotland (1996)

- ↑ Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, 1999

- ↑ Wolff, Stefan; Jorg (EDT) Neuheiser (1 January 2002). Peace at Last?: The Impact of the Good Friday Agreement on Northern Ireland. Berghahn Books. ISBN.

- ↑ Pagoeta, Mikel Morris (2001). Europe Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. p. 416. ISBN 978-1741799736.

- ↑ "UK | Mixed report on Gaelic language". BBC News. 10 October 2005. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑

- ↑ MacDonald, James Ramsay (1921). Socialism: critical and constructive. Cassell's social economics series. Cassell and Company Ltd.

- ↑ Lehane, Brendan (26 January th, 2000). The Quest of Three Abbots: the golden age of Celtic Christianity. SteinerBooks. p. 121. ISBN. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Harris, Stephen J. (1 October 2003). Race and Ethnicity in Anglo-Saxon Literature. Routledge (UK). p. 72. ISBN.

- ↑ Martin, F. X. (Francis Xavier); Theodore William Moody, F. J. (Francis John) Byrne (1 August 1976). New History of Ireland. Oxford University Press. p. 862. ISBN.

- ↑ Freer, Allan (1871). The North British Review. Edmonston & Douglas. p. 119. and Robertson, Eben William (1862). Scotland Under Her Early Kings: a history of the kingdom to the close of the thirteenth century. Edmonston and Douglas. p. 286.

- ↑ Greenway, D. E. (EDT); E. B. (Edmund Boleslaw) Fryde (1 June 1996). Handbook of British Chronology. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780521563505.

- ↑ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language Scotch usage note, Encarta Dictionary usage note.

- ↑ "Definition of scotch". Askoxford.com. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Celts and Modern Celts |

|---|

|

Nations |

|

Texts and Chronicles

|

|

Politics Celtic League |

|

Celtic Art

|

|

Society

|

|

Music

|

References

- Ritchie, A. & Breeze, D.J. Invaders of Scotland HMSO. (?1991)

- David Armitage, "The Scottish Diaspora" in Jenny Wormald (ed.), Scotland: A History. Oxford UP, Oxford, 2005.

Further reading

- Spence, Rhoda, ed. The Scottish Companion: a Bedside Book of Delights. Edinburgh: R. Paterson, 1955. vi, 138 p. N.B.: Primarily concerns Scottish customs, character, and folkways.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of Scotland. |

- The Scots In New Zealand Exhibition Minisite from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- "We're nearly all Celts under the skin" by Ian Johnston for The Scotsman Online

- Top 100 Scottish People

- Biographies of Famous Scots at Scottish-people.info, part of the Gazetteer for Scotland project

- Discover your Scottish family history at the official government resource for Scottish Genealogy

- Scottish Emigration Database of the University of Aberdeen