Scottish art in the Prehistoric era

Scottish art in the Prehistoric era includes all visual art created within the modern borders of Scotland, before the departure of the Romans from southern and central Britain in the early fifth century CE.

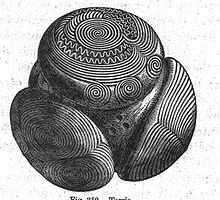

The earliest examples of art from what is now Scotland are highly decorated carved stone balls from the Neolithic period, which share patterns with Irish and Scottish stone carvings. Other items from this period include elaborate carved maceheads and figurines from Links of Noltland, including the Westray Wife, the last of which is the earliest known depiction of a human face from Scotland.

From the Bronze Age there are examples of carvings, including the first representations of objects, and cup and ring marks. Representations of an axe and a boat at the Ri Cruin Cairn in Kilmartin, and a boat pecked into Wemyss Cave, are probably the oldest two-dimensional representations of real objects that survive in Scotland. Elaborate carved stone battle-axes may be symbolic representations of power. Surviving metalwork includes gold lunula or neckplates, jet beaded necklaces and elaborate weaponry, such as leaf swords and ceremonial shields of sheet bronze.

From the Iron Age there are more extensive examples of patterned objects and gold work. Evidence of the wider La Tène culture includes the Torrs Pony-cap and Horns. The Stirling torcs demonstrate common styles found in Scotland and Ireland and continental workmanship. One of the most impressive items from this period is the boar's head fragment of the Deskford carnyx. From the first century CE, Roman influence on material culture can be seen in stone carvings.

Stone Age

Scotland was occupied by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from around 8500 BCE,[1] who were highly mobile boat-using people making tools from bone, stone and antlers.[2] Neolithic farming brought permanent settlements, like the stone house at Knap of Howar on Papa Westray, dating from around 3500 BCE.[3] The settlers introduced chambered cairn tombs from around 3500 BCE, as at Maeshowe,[4] and from about 3000 BCE the many standing stones and circles such as those at Stenness on the mainland of Orkney, which date from about 3100 BCE.[5] These were part of a pattern that developed in many regions across Europe at about the same time.[6]

Probably the oldest examples of portable visual art to survive from Scotland are carved stone balls, or petrospheres, that date from the late Neolithic era. They are a uniquely Scottish phenomenon, with over 425 known examples. Most are from modern Aberdeenshire,[7] but a handful of examples are known from Iona, Skye, Harris, Uist, Lewis, Arran, Hawick, Wigtownshire and fifteen from Orkney, five of which were found at the Neolithic village of Skara Brae.[8] Many functions have been suggested for these objects, most indicating that they were prestigious and powerful possessions.[7] Their production may have continued into the Iron Age.[9] The complex carved circles and spirals on these balls can be seen mirrored in the carving on what was probably a lintel from a chambered cairn at Pierowall on Westray, Orkney, which seem to be part of the same culture that produced carvings at Newgrange in Ireland.[10] Similarly, elaborately carved maceheads are often found in burial sites, like that found at Airdens in Sutherland, which has a pattern of interlocking diamond-shaped facets, similar to those found across Neolithic Britain and Europe.[10]

Finely made and decorated Unstan ware, survives from the fourth and third millennia BCE and is named after the Unstan Chambered Cairn on the Mainland of the Orkney Islands.[11] Typical are elegant and distinctive shallow bowls with a band of grooved patterning below the rim,[12] using a technique known as "stab-and-drag". A second variation consists of undecorated, round-bottomed bowls.[13] Unstan ware is mostly found in tombs, specifically tombs of the Orkney-Cromarty type,[14] that include the so-called Tomb of the Eagles at Isbister on South Ronaldsay, and Taversoe Tuick and Midhowe on Rousay, but has occasionally been found outside of tombs, as at the farmstead of Knap of Howar on Papa Westray.[15] There are scattered occurrences of Unstan ware on the Scottish Mainland, as at Balbridie,[16] and in the Western Isles, as at Eilean Domhnuill.[17] Unstan ware may have evolved into the later grooved ware style,[18] associated with the builders of the Maeshowe class of chambered tomb, which began on Orkney early in the third millennium BCE, and was soon adopted throughout Britain and Ireland.[19] Grooved ware vessels are often highly decorated and flat bottomed, often with patterns similar to those on petrospheres and carved maceheads.[20]

In 2009 the Westray Wife, a lozenge-shaped figurine that is believed to be the earliest representation of a human face ever found in Scotland, was discovered at the site of a Neolithic village at Links of Noltland near Grobust Bay on the north coast of Westray. The figurine's face has two dots for eyes, heavy brows and an oblong nose and a pattern of hatches on the body could represent clothing.[21] Two figurines were subsequently found at the site in 2010 and 2012.[22]

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age began in Scotland about 2000 BCE.[23] From this period there are extensive examples of rock art. These include cup and ring marks, a central depression carved into stone, surrounded by rings, sometimes not completed. These are common elsewhere in Atlantic Europe and have been found on natural rocks and isolated stones across Scotland. The most elaborate sets of markings are in western Scotland, particularly in the Kilmartin district. The representations of an axe and a boat at the Ri Cruin Cairn in Kilmartin, and a boat pecked into Wemyss Cave, are probably the oldest two-dimensional representations of real objects that survive in Scotland. Similar carved spirals have also been found on the cover stones of burial cists in Lanarkshire and Kincardine.[24]

There are also elaborate carved stone battle-axes found in East Lothian, Aberdenshire and Lanarkshire. These show little sign of use or wear, so may be symbolic representations of power.[25] Similarly, the site at Forteviot, in Perthshire produced a unique warrior burial under a giant sandstone slab engraved with a spiral and an axehead, pecked into the underside. There are grave goods of a copper dagger with leather scabbard and a carved wooden bowl.[26]

Surviving metalwork includes personal items like the gold lunula or neckplates found at Auchentaggart in Dumfriesshire and Southside, Lanarkshire, which date from about 2000 BCE and follow a pattern found particularly in Ireland, but also across Britain and in Portugal.[27] Jet beaded necklaces strung in a crescent shape have been found at sites including Poltalloch and Melfort in Argyll and Aberlemno in Angus.[27]

Pottery appeared in the Neolithic period once hunters and gatherers transitioned to a sedentary lifestyle, until then they needed to use lightweight, mobile containers. Sophisticated pottery with impressed designs was found in Scotland during the Bronze Age. One example is a decorated grave food vessel dated from about 1000 BCE that was found at a Kincardineshire grave group. Two bronze armlets were also found at the site.[28]

Elaborate weaponry includes bronze leaf swords and ceremonial shields of sheet bronze made in Scotland between 900 and 600 BCE.[27] The Migdale Hoard is an early Bronze Age find at Skibo Castle that includes two bronze axes; several pairs of armlets and anklets, a necklace of forty bronze beads, ear pendants and bosses of bronze and jet buttons.[29][30] The "Ballachulish Goddess" is a life-sized female figure from 700–500 BCE in oak with quartz pebbles for eyes, found at Ballachulish, Argyll.[31]

Iron Age

By the early Iron Age, from the seventh century BCE, Scotland had been penetrated by the wider La Tène culture.[32] The Torrs Pony-cap and Horns are perhaps the most impressive of the relatively few finds of La Tène decoration from Scotland, and indicate links with Ireland and southern Britain.[33] The Stirling torcs, found in 2009, are a group of four gold torcs in different styles, dating from 300 BCE and 100 BCE. Two demonstrate common styles found in Scotland and Ireland, but the other two indicate workmanship from what is now southern France, and the Greek and Roman worlds.[34] The bronze Stichill collar is a large engraved necklace, fastened at the back with a pin. The Mortonhall scabbard, probably from the first century CE, is elaborately decorated with trumpet curves and "S"-scrolls. Further north there are finds of massive bronze armlets, often with enameled decoration, like the ones found at Culbin Sands, Moray.[35] One of the most impressive items from this period is the boars head fragment of the Deskford carnyx, a war-trumpet from Deskford in Banffshire, probably dating from the first century CE. Similar instruments are mentioned in Roman sources and depicted on the Gundestrup Cauldron found in Denmark.[36]

Roman influence

The Romans began military expeditions into what is now Scotland from about 71 CE, building a series of forts, but by 87 CE the occupation was limited to the Southern Uplands and by the end of the first century the northern limit of Roman expansion was a line drawn between the Tyne and Solway Firth.[37] The Romans eventually withdrew to a line in what is now northern England, building the fortification known as Hadrian's Wall from coast to coast.[38] Around 141 CE they undertook a reoccupation of southern Scotland, moving up to construct a new limes between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde, where they built the fortification known as the Antonine Wall. The wall was overrun and abandoned soon after 160 CE and the Romans withdrew back to the line of Hadrian's Wall,[38][39][40] until Roman authority collapsed in the early fifth century.[41] This presence left behind a number of objects that indicate a Roman artistic influence. These include the Cramond Lioness, a sculpture, probably imported, of a lioness devouring a bound prisoner, found near the Roman base of Cramond Roman Fort near Edinburgh. A relief of the goddess Brigantia found near Birrens in Dumfriesshire, combines elements of native and classical art.[42] The Newstead Helmet is one of the most impressive of many finds of Roman arms and armour.[43] The Staffordshire Moorlands Pan is a second-century Romano-British trulla apparently decorated as a souvenir for a soldier who had served on Hadrian's Wall, and probably made locally.[44] A number of items were also found in the Sculptor's Cave, Coversea in Morayshire, including Roman pottery, rings, bracelets, needles and coins, some of which had been re-used for ornaments.[45]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prehistoric art in Scotland. |

References

Notes

- ↑ "Signs of Earliest Scots Unearthed". BBC News. 9 April 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ↑ P. J. Ashmore, Neolithic and Bronze Age Scotland: an Authoritative and Lively Account of an Enigmatic Period of Scottish Prehistory (London: Batsford, 2003), ISBN 0713475307, p. 46.

- ↑ I. Maxwell, "A History of Scotland’s Masonry Construction" in P. Wilson, ed., Building with Scottish Stone (Edinburgh: Arcamedia, 2005), ISBN 1-904320-02-3, p. 19.

- ↑ F. Somerset Fry and P. Somerset Fry, The History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 1992), ISBN 0710090013, p. 7.

- ↑ C. Wickham-Jones, Orkney: A Historical Guide (Birlinn, 2007), 0857905910, p. 28.

- ↑ F. Lynch, Megalithic Tombs and Long Barrows in Britain (Bodley: Osprey, 1997), ISBN 0747803412, p. 9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Carved stone ball found at Towie, Aberdeenshire", National Museums of Scotland, retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ D. N. Marshall, "Carved Stone Balls", Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 108 (1976/77), pp. 62–3.

- ↑ J. Neil, G. Ritchie and A. Ritchie, Scotland, Archaeology and Early History, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd end., 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0291-7, p. 46.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 M. MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, pp. 10-11.

- ↑ A. Ritchie, "The First Settlers", in C. Renfrew, ed., The Prehistory of Orkney BC 4000-1000 AD (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1985), ISBN 0-85224-456-8, p. 48.

- ↑ A. Henshall, "The Chambered Cairns", in C. Renfrew, ed., The Prehistory of Orkney BC 4000-1000 AD (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1985), ISBN 0-85224-456-8. p. 88.

- ↑ L. Laing, Orkney and Shetland: An Archaeological Guide (Newton Abbott: David and Charles Ltd, 1974), ISBN 0-7153-6305-0, p. 51.

- ↑ Henshall, "The Chambered Cairns", p. 110.

- ↑ A. Ritchie, Prehistoric Orkney (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1995), ISBN 0-7134-7593-5, pp. 52 and 54.

- ↑ N. Reynolds, and I. Ralston, Balbridie, Discovery and Excavation in Scotland 1979 (Edinburgh: Council for British Archaeology: Scottish Regional Group, 1979).

- ↑ A. Henshall, The Chambered Tombs of Scotland Vol. 2 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 1979), p. 177.

- ↑ D. V. Clarke, "Rinyo and the Orcadian Neolithic", in A. O'Connor and D. V. Clarke, eds, From the Stone Age to the 'Forty Five: Studies presented to R. B. K. Stevenson (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1983), ISBN 0859760464, pp. 49-51.

- ↑ J. W. Hedges, Tomb of the Eagles: Death and Life in a Stone Age Tribe (New York: New Amsterdam, 1985), ISBN 0-941533-05-0, pp. 118-119.

- ↑ G. Noble, Neolithic Scotland: Timber, Stone, Earth and Fire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), ISBN 074862337X, p. 19.

- ↑ Urquhart, Frank (21 August 2009). "Face to face with the 5,000-year-old 'first Scot'". Edinburgh: The Scotsman. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ↑ "Third 5,000-year-old figurine found at Orkney dig". BBC News. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ↑ C. Scarre, Monuments and Landscape in Atlantic Europe: Perception and Society During the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (London: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0415273137, p. 125.

- ↑ V. G. Childe, The Prehistory Of Scotland (London: Taylor and Francis, 1935), p. 115.

- ↑ M. MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, p. 12.

- ↑ N. Oliver, A History of Ancient Britain (Hachette UK, 2011), ISBN 0297867687.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 "Collar from Southside, Lanarkshire, National Museums of Scotland, retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ Paul G. Bahn (1998). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-521-45473-5.

Image of the vessel is also on this page.

- ↑ J. Anderson,(1901) "Notice of a hoard of bronze implements, and ornaments, and buttons of jet found at Migdale, on the estate of Skibo, Sutherland, exhibited to the society by Mr. Andrew Carnegie of Skibo". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Retrieved 21 Aug 2011.

- ↑ "Anklets of Bronze" National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ↑ I. Armit, "The Iron Age" in D. Omand, ed., The Argyll Book (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2006), ISBN 1-84158-480-0, p. 58.

- ↑ R. G. Collingwood and J. N. L. Myres, Roman, Britain and the English Settlements (New York, NY: Biblo & Tannen, 2nd edn., 1936), ISBN 978-0-8196-1160-4, p. 25.

- ↑ J. Neil, G. Ritchie and A. Ritchie, Scotland, Archaeology and Early History, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd end., 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0291-7, p. 119.

- ↑ "Iron Age Gold", National Museums of Scotland, retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ R. Megaw and J. V. S. Megaw, Early Celtic Art in Britain and Ireland (Bodley: Osprey, 2nd edn., 2008), ISBN 0747806136, pp. 72-4.

- ↑ M. MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, p. 16.

- ↑ W. S. Hanson, "The Roman Presence: Brief Interludes", in K. J. Edwards, I. B. M. Ralston, eds, Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC - AD 1000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1736-1, p. 195.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "History", antoninewall.org, retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ↑ D. J. Breeze, The Antonine Wall (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2006), ISBN 0-85976-655-1, p. 167.

- ↑ A. Moffat, Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005), ISBN 0-500-28795-3, pp. 297–301.

- ↑ W. S. Hanson, "The Roman presence: brief interludes", in K. J. Edwards and I. B. M. Ralston, eds, Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC - AD 1000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1736-1, p. 198.

- ↑ M. MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, pp. 16-7.

- ↑ "Parade helmet and face mask". National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ "The Staffordshire Moorlands Pan", British Museum, retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ "Site Record for Sculptor's Cave Covesea", Historic Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotland, retrieved 4 March 2014.

Bibliography

- Anderson, J., "Notice of a hoard of bronze implements, and ornaments, and buttons of jet found at Migdale, on the estate of Skibo, Sutherland, exhibited to the society by Mr. Andrew Carnegie of Skibo", Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

- Armit, I., "The Iron Age" in D. Omand, ed., The Argyll Book (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 1901, 2006), ISBN 1-84158-480-0.

- Ashmore, P. J., Neolithic and Bronze Age Scotland: an Authoritative and Lively Account of an Enigmatic Period of Scottish Prehistory (London: Batsford, 2003), ISBN 0713475307.

- Breeze, D. J., The Antonine Wall (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2006), ISBN 0-85976-655-1.

- Childe, V. G., The Prehistory Of Scotland (London: Taylor and Francis, 1935).

- Clarke, D. V., "Rinyo and the Orcadian Neolithic", in A. O'Connor and D. V. Clarke, eds, From the Stone Age to the 'Forty Five: Studies presented to R. B. K. Stevenson (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1983), ISBN 0859760464.

- Collingwood, R. G., and Myres, J. N. L., Roman, Britain and the English Settlements (New York, NY: Biblo & Tannen, 2nd edn., 1936), ISBN 978-0-8196-1160-4.

- Hanson, W. S., "The Roman Presence: Brief Interludes", in K. J. Edwards, I. B. M. Ralston, eds, Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC - AD 1000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1736-1.

- Hedges, J. W., Tomb of the Eagles: Death and Life in a Stone Age Tribe (New York: New Amsterdam, 1985), ISBN 0-941533-05-0.

- Henshall, A., The Chambered Tombs of Scotland Vol. 2 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 1979).

- Henshall, A., "The Chambered Cairns", in C. Renfrew, ed., The Prehistory of Orkney BC 4000-1000 AD (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1985), ISBN 0-85224-456-8.

- Laing, L., Orkney and Shetland: An Archaeological Guide (Newton Abbott: David and Charles Ltd, 1974), ISBN 0-7153-6305-0,

- Lynch, F., Megalithic Tombs and Long Barrows in Britain (Bodley: Osprey, 1997), ISBN 0747803412.

- MacDonald, M., Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334.

- Marshall, D. N., "Carved Stone Balls", Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 108 (1976/77).

- Maxwell, I., "A History of Scotland’s Masonry Construction" in P. Wilson, ed., Building with Scottish Stone (Edinburgh: Arcamedia, 2005), ISBN 1-904320-02-3.

- Megaw, R., and Megaw, J. V. S., Early Celtic Art in Britain and Ireland (Bodley: Osprey, 2nd edn., 2008), ISBN 0747806136.

- Moffat, A., Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005), ISBN 0-500-28795-3.

- Neil, J., Ritchie, G., and Ritchie, A., Scotland, Archaeology and Early History (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd end., 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0291-7.

- Oliver, N., A History of Ancient Britain (Hachette UK, 2011), ISBN 0297867687.

- Reynolds, N. and Ralston, I., Balbridie, Discovery and Excavation in Scotland 1979 (Edinburgh: Council for British Archaeology: Scottish Regional Group, 1979).

- Ritchie, A., "The First Settlers", in C. Renfrew, ed., The Prehistory of Orkney BC 4000-1000 AD (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1985), ISBN 0-85224-456-8.

- Ritchie, A., Prehistoric Orkney (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1995), ISBN 0-7134-7593-5

- Scarre, C., Monuments and Landscape in Atlantic Europe: Perception and Society During the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (London: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0415273137.

- Somerset Fry, F., and Somerset Fry, P., The History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 1992), ISBN 0710090013.

- Wickham-Jones, C., Orkney: A Historical Guide (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2007), ISBN 0857905910.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||