Scientific Detective Monthly

Scientific Detective Monthly was a pulp magazine which published fifteen issues beginning in January 1930. It was launched by Hugo Gernsback as part of his second venture into science fiction magazine publishing, and was intended to focus on detective and mystery stories with a scientific element. Many of the stories involved contemporary science without any imaginative elements—for example, a story in the first issue turned on the use of a bolometer to detect a black girl blushing—but there were also one or two science fiction stories in every issue.

The title was changed to Amazing Detective Tales with the June 1930 issue, perhaps to avoid the word "scientific", which may have given readers the impression of "a sort of scientific periodical", in Gernsback's words, rather than an magazine intended to entertain. At the same time the editor, Hector Grey, was replaced by David Lasser, who was already editing Gernsback's other science fiction magazines. The title change apparently did not make the magazine a success, and Gernsback closed the magazine down with the October issue. He sold the title to publisher Wallace Bamber, who produced at least five more issues in 1931 under the title Amazing Detective Stories.

Publication history and contents

By the end of the 19th century, stories centered on scientific inventions and set in the future, in the tradition of Jules Verne, were appearing regularly in popular fiction magazines.[1] The first science fiction (sf) magazine, Amazing Stories, was launched in 1926 by Hugo Gernsback at the height of the pulp magazine era.[2][3] It was successful, and helped to form science fiction as a separately marketed genre, but in February 1929 Gernsback lost control of the publisher when it went bankrupt.[4][5] By April he had formed a new company, Gernsback Publications Incorporated, and created two subsidiaries: Techni-Craft Publishing Corporation and Stellar Publishing Corporation; in the middle of the year he launched three new magazines: Radio Craft, and two sf pulps: Science Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories.[6] In the January 1930 issue of both these magazines, Gernsback advertised another new title: Scientific Detective Monthly.[7]

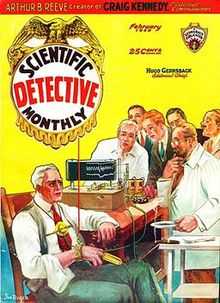

Gernsback believed that science fiction was educational, claiming, for example, that "teachers encourage the reading of this fiction because they know that it gives the pupil a fundamental knowledge of science and aviation."[8] He intended Scientific Detective Monthly to be a detective magazine in which the stories had a scientific background; which would entertain, but also instruct. The first issue was dated January 1930 (which meant it would have been on the newsstands in mid-December 1929). Gernsback was editor-in-chief, and had final say-so on the choice of stories, but the editorial work was done by Hector Grey, the editorial deputy. The cover for the first issue, by Jno Ruger, showed a detective using an electronic device to measure the reactions of a suspect.[7]

The stories in Scientific Detective Monthly were almost always detective stories, but they were only occasionally science fiction, as in many cases the science appearing in the stories already existed in real life. In the first issue, for example, "The Mystery of the Bulawayo Diamond", by Arthur B. Reeve, mentions unusual science, but the mystery is solved by use of a bolometer to detect a blush on the face of a black girl. The murderer in "The Campus Murder Mystery", by Ralph W. Wilkins, freezes the body to conceal the manner of death; and in two more stories in the same issue, a chemical catalyst, and electrical measurements of palm sweat, provide the scientific element. The only story in the first issue that is genuinely science fiction is "The Perfect Counterfeit" by Captain S.P. Meek, in which a matter duplicator has been used to counterfeit paper money. Throughout the magazine's run, only one or two stories per issue including elements that would qualify them as science fiction.[7]

In addition to fiction, there were some non-fiction departments, including reader's letters (even in the first issue—Gernsback obtained letters by advertising the magazine to readers who subscribed to his other magazines), book reviews, an editorial, and miscellaneous crime or science-related fillers. The first issue included a test of the readers' powers of observation: it showed a crime scene, which the readers were supposed to study, and then posed questions to see how much they could remember of the details. There was also a questionnaire about science, which asked about scientific facts mentioned in the stories; and a "Science-Crime Notes" section which contained news items about science and crime.[7]

With the June issue, the title was changed to Amazing Detective Tales. The reason is not known, but Gernsback merged Science Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories into Wonder Stories at the same time; he was concerned that the word "Science" was putting off some potential readers, who assumed that the magazine was "a sort of scientific periodical", in his words.[7][9] It is likely that the same reasoning motivated Scientific Detective Monthly's new title. In the following issue, Grey was replaced as editor by David Lasser, who was already editing Gernsback's other sf titles, and an attempt was made to include more stories with science fiction elements. Gernsback continued the magazine for five more issues under the new title; the last issue was dated October 1930. The decision to cease publication was apparently taken suddenly, as the October issue included the announcement that the format would change in November from large pulp to pulp size, and listed two stories planned for the November issue.[7][10] Gernsback sold the title to Wallace Bamber, who published at least five more issues, starting in February 1931; no issues are known for June or July 1931, or after August.[10]

The first few covers did not advertise the names of the authors whose work was inside, which was probably a mistake as existing science fiction readers might have been attracted by the names of writers they were familiar with. Conversely, the readers who might have been interested in the more sedate topics covered by the non-fiction were probably discouraged by the lurid cover artwork. Gernsback was unable to obtain enough fiction to make Scientific Detective Monthly a true mixture of the two genres, and the result was a magazine that failed to fully appeal to fans of either genre. The magazine was, in sf historian Robert Lowndes' words, a "fascinating experiment", but a failed one.[7]

Bibliographic details

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1/5 | 1/6 | 1/7 | 1/8 | 1/9 | 1/10 | ||

| 1931 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | 3/1 | |||||||

| Issues of Scientific Detective Monthly, showing volume/issue number, and color-coded to indicate the managing editor: Hector Grey (blue), David Lasser (yellow), and unknown (orange)[7][11] | ||||||||||||

Scientific Detective Monthly was published by Techni-Craft Publishing Co. of New York for the first ten issues, and then by Fiction Publishers, Inc., also of New York. The editor-in-chief was Hugo Gernsback for the first ten issues; the managing editor was Hector Grey for the first six issues, and David Lasser for the next four. The editor for the 1931 issues is not known. The first volume contained ten numbers; the second volume contained four numbers; and the final volume contained only a single number. The title changed to Amazing Detective Tales with the June 1930 issue, and again to Amazing Detective Stories in February 1931. The magazine was in large pulp format throughout; it was 96 pages long and priced at 25 cents.[7]

Footnotes

- ↑ Ashley (2000), pp. 6−27.

- ↑ Ashley, Mike; Nicholls, Peter; Stableford, Brian (8 July 2014). "Amazing Stories". SF Encyclopedia. Gollancz. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ↑ Clareson (1985), p. xxiii.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), pp. 58−59.

- ↑ Bleiler (1998), p. 548.

- ↑ Bleiler (1998), p. 579.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Lowndes (1985), pp. 556−562.

- ↑ Bleiler (1998), p. 542.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), p. 71.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ashley (2000), p. 66.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), p. 248.

References

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines:The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Bleiler, Everett F. (1998). Science-Fiction: The Gernsback Years. Westport, Connecticut: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-604-3.

- Clareson, Thomas A. (1985). "Introduction". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike. Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. xv–xxviii. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Lowndes, Robert A. (1985). "Scientific Detective Monthly". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike. Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 556–562. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.