Saxtuba

| |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

|

Saxhorn, Saxotromba Trumpet, Bugle Tuba, Wagner tuba Cornu, Buccina, Roman tuba | |

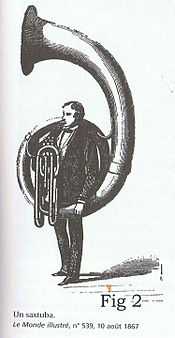

The saxtuba is an obsolete valved brasswind instrument conceived by the Belgian instrument-maker Adolphe Sax around 1845.[1] The design of the instrument was inspired by the ancient Roman cornu and tuba. The saxtubas, which comprised a family of half-tube and whole-tube instruments of varying pitches, were first employed in Fromental Halévy's opera Le Juif errant (The Wandering Jew) in 1852. Their only other public appearance of note was at a military ceremony on the Champ de Mars in Paris in the same year.

History

In the 1770s, the French artist Jacques-Louis David carried out extensive researches into the ancient Roman instruments that appeared on Trajan's Column in Rome. Two of these instruments – the straight tuba and the curved cornu – were revived in Revolutionary France as the buccin and tuba curva.[3] To devise the saxtubas Sax merely added valves to these natural instruments, thus providing them with chromatic compasses. Furthermore, he designed them in such a way that the valves were hidden from general view, thus giving the impression that the instruments were primitive natural trumpets only capable of playing notes from a single harmonic series.

The saxtuba was apparently first conceived by Sax at his workshop in the Rue Saint-Georges in Paris around 1845.[4] On 5 May 1849 Sax applied for a patent for a series of brasswind instruments fitted with cylinders. On 16 July 1849 he was granted French Patent 8351.[5] Like Sax's saxhorns and saxotrombas, which were also covered by this patent, the saxtubas were equipped with pavillons tournants – that is to say, their bells pointed forward – which was considered ideal for instruments intended to be played by marching or mounted bands in the open air.

The cylinders referred to in the patent application were piston valves which allowed the player to lower the pitch of the instrument's natural or open harmonics by one or more semitones. In 1843 Sax had patented his own version of the Berlin piston valve (i.e. the Berliner Pumpenventil, which had been invented independently by Heinrich Stölzel in 1827 and Wilhelm Friedrich Wieprecht in 1833). These were independent valves, which were not designed to be used in combination with one another, though the intonational problems that arose when they were so used could often be corrected by the player's technique.[6] This was especially true in the case of the higher-pitched half-tube instruments, which were usually provided with just three valves, allowing the player to lower the pitch of any open note by one, two or three semitones when the valves were used one at a time, or by four, five or six semitones when the valves were used in combination. Before the invention of compensating valves (which could be used in combination without producing faulty intonation), lower-pitched instruments generally required extra valves in order to lower the pitch of an open note by more than three semitones.

In 1859 Sax applied his system of six independent valves to the saxtuba.[7]

The saxtubas made their first public appearance at the première of Fromental Halévy's opera Le Juif errant (The Wandering Jew) at the Paris Opéra on 23 April 1852. At the time, Sax was musical director of the Opéra's stage band (or banda), so it was not unusual for instruments of his design to be showcased in popular productions. Although Sax appears to have designed the saxtuba as early as 1845, it is possible that he did not actually manufacture any specimens until they were required for Le Juif errant in 1852.

In the opera, the saxtubas are first heard on stage in the Triumphal March (No. 17) at the end of Act III. A total of eight different sizes of saxtuba were required to play ten individual parts.[8] Curiously, the saxtubas are not referred to by this name in the only surviving copy of the full score;[9] instead they are listed as saxhorns, which suggests that the decision to use saxtubas was a late one. In the score the instruments are designated as follows:

|

|

|

The only other appearance of the stage band in the opera occurs in the Judgment dernier ("Last Judgment") in Act V, which also includes parts for four saxophones, one of which was played by Sax himself.[10] On both occasions the performers are instructed to march across the stage, playing martial music typical of the period as they do so. This music has been compared to the Apothéose from Berlioz's Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale of 1840. François-Joseph Fétis, who reviewed the opera's première, reported that the sound of the Sax's saxtuba banda was out of all proportion to that of the orchestra in the pit. At subsequent performances the instruments were muted, which resulted in a much better balance between the two bodies.[11]

Le Juif errant was not a success, despite being given fifty times over two seasons at the Paris Opéra;[12] when it disappeared from the repertoire, it took the saxtuba with it. The only other notable public appearance of the saxtubas occurred less than a month after the opera's première, on 10 May 1852, when twelve saxtubas participated in a military ceremony on the Champ de Mars, Paris, in which the President of the French Republic Louis Napoleon distributed the colours to his army. Although a total of 1500 musicians from thirty regiments were employed in the ceremony, the twelve saxtubas overwhelmed all the other instruments. According to an eyewitness the saxtubas were played by the same civilian players who had played them at the Opéra the previous month.[13]

The existence of a few saxtubas from the late nineteenth or early twentieth century – including six specimens manufactured by Sax's son Adolphe-Edouard – suggests that the instrument did not become completely obsolete after the disappearance of Le Juif errant from the repertoire. Records preserved in the Bibliothèque-Musée de l'Opéra National de Paris indicate sporadic appearances of saxtubas of various sizes in operatic productions throughout the late nineteenth century, both as solo instruments in the pit and as theatrical instruments in the onstage banda. Jules Massenet added a saxtuba to his pit orchestra in Le Roi de Lahore (1877);[14] Charles Gounod used the same instrument in Le tribut de Zamora in 1881.[15] Massenet also wrote a solo for contrabass saxtuba in C in Esclarmonde, which was first performed at the Opéra-Comique in 1889.[16]

Sources

In 1855, in a revised version of his Treatise on Instrumentation, the French composer Hector Berlioz described several of Sax's newly invented instruments, including the saxtubas:

These are instruments with mouth-piece[17] and a mechanism of three cylinders; they are of enormous sonorousness, carrying far, and producing extraordinary effect in military bands intended to be heard in the open air. They should be treated exactly like sax-horns; merely taking into account the absence of the low double-bass in E♭, and of the drone in B♭. Their shape—elegantly rounded—recalls that of antique trumpets on a grand scale.[18]

This description was repeated verbatim in an article Berlioz contributed to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular five years later.[19] It should be noted that the two contrabass instruments which Berlioz says are lacking (the double-bass [contrebasse] in E♭ and the drone [bourdon] in B♭) are in fact included among the eight different sizes of saxtubas that took part in Halévy's Le Juif errant.

The saxtuba is often mistaken for one of the larger members of Sax's saxhorn family. In 1908 W. L. Hubbard defined the term saxtuba thus:

The bass saxhorn; a brass bass wind instrument similar to the saxotromba, and one of the family of brass instruments invented by Adolphe Sax. It has three cylinders or pistons for regulating the pitch, a wide mouthpiece, and possesses a deep sonorous tone.[20]

The saxtuba has no entry in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, but the New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments describes it as "a brass instrument in the circular form of the Roman buccina," adding that it has "three valves and was made in seven sizes from piccolo in B♭ to contrabass in B♭."[21]

Acoustic principles of the saxtuba family

From the surviving copy of Halévy's opera, it would appear that the saxtubas were made in the same pitches as the saxhorns: indeed, it is quite probable that they were deliberately designed by Sax as substitutes for the saxhorns, whose music had already been composed. Berlioz claimed that the two deepest instruments (corresponding to the contrabass saxhorns listed above) did not exist, but this seems to be contradicted by both the surviving score and eyewitness accounts of Halévy's opera.[22]

In his Treatise on Instrumentation Berlioz described nine different sizes of saxhorn. These correspond to those listed above with one addition: a small sopranino in C:[23] Forsyth's Orchestration (1914) includes seven of these, though the nomenclature is quite different, as the following table shows:

|

|

|

|

Of these, only the bottom three were whole-tube instruments capable of sounding their fundamentals. The remaining instruments were half-tube instruments, whose series of natural harmonics only descended as far as the second harmonic. Presumably the same applied to the saxtubas: some of the extant saxtubas have only three valves, while some have four valves.

The saxtuba was a brasswind instrument. It was constructed in such a way that the column of air inside the instrument was capable of vibrating at a number of different pitches that corresponded to the notes of the harmonic series. These pitches are known as the instrument's natural or normal modes of vibration, each one being a natural harmonic or open note. By vibrating his lips at the correct frequency, the player was able to compel the instrument's air column to vibrate at the correct pitch; by lipping, he could correct the minor intonational defects due to the discrepancies between the natural harmonic series and the tempered scales of classical music.

Like the modern valve trumpet and cornet, the first six saxtubas employed harmonics two through eight; the three lowest-pitched saxtubas employed harmonics one through eight.[24] The seventh harmonic was too much out of tune to be lipped; this partial was generally avoided by trumpeters and cornet players after the introduction of valves.

In order to provide a half-tube saxtuba with a chromatic compass from the second harmonic upwards, it is essential to provide the player with some means of lowering the pitch of the third harmonic by as many as six semitones, this being the size of the gap between the second and third harmonics. Three independent valves will reduce the pitch of a natural or open harmonic by two, one and three semitones respectively. Used singly or in combination, these can bridge the gap between the second and third harmonics, though the player will be required to correct by lipping the faulty intonation produced when independent valves are used in combination. The gaps between the higher harmonics are smaller still, so no more than three valves are required to provide such an instrument with a full chromatic compass; this is true even if the seventh harmonic is not used.

The whole-tube saxtubas require at least four valves for a fully chromatic range from the fundamental upwards, as the gap between the first and second harmonics is a full octave. Valves that lower the pitch of an open note by one, two, three and five semitones can be used alone or in combination to supply all eleven notes that lie between the first two harmonics. Later models of saxtuba were provided with six independent valves, lowering the pitch of an open harmonic by one through six semitones, thus removing completely the need to use any valves in combination.[25]

Compass

Like the saxhorn, the saxtuba was a transposing instrument. According to Berlioz, its music was always written in the treble clef as though for an instrument pitched in C, but the actual sounds produced depended on the size of instrument used. For example, if a piece of music were performed on Halévy's soprano saxtuba in E-flat, it would sound a minor third higher than written. Halévy's score of Le Juif errant is in general agreement with this, though, curiously, the part for the bass saxtuba in B♭ ("Sax horn basse en Si♭") is notated in the bass clef, sounding just one whole-tone lower than written.

In the following table, all eight saxtubas from Le Juif errant and the contrabass saxtuba in C from Massenet's Esclarmonde have been included with their probable ranges. I have followed Forsyth (1914):

| Name | Key | Fundamental | Transposition | Sounding Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sopranino | B♭ | | minor seventh higher | |

| Soprano | E♭ | | minor third higher | |

| Alto | B♭ | | major second lower | |

| Tenor | E♭ | | major sixth lower | |

| Baritone | B♭ | | major ninth lower | |

| Bass | B♭ | | major ninth lower | |

| Bass | E♭ | | major thirteenth lower | |

| Contrabass | C | | two octaves lower | |

| Contrabass | B♭ | | octave plus a major ninth lower | |

Extant saxtubas

Of the saxtubas manufactured by Adolphe Sax's firm, about half a dozen have survived to the present day. The following table includes one instrument which was lost during World War II:[26]

| Year | Key | Valves | Location | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1855 | E♭ | 3 Berlin piston valves | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York | |

| 1855 | B♭ | Musikinstrumenten-Museum, Berlin | lost during World War II | |

| 1855 | E♭ | 3 Berlin piston valves | Trompetenmuseum, Bad Säckingen | |

| 1895–1907 | 4 valves | Musée de la Musique, Paris | pavillon pivotant | |

| 1895–1907 | Musée de la Musique, Paris | Adolphe-Edouard Sax | ||

| c. 1900 | 4 piston valves | Musée de la Musique, Paris | Adolphe-Edouard Sax pavillon pivotant | |

| c. 1900 | Musée de la Musique, Paris | |||

| 1907–28 | 3 piston valves | Paris | Adolphe-Edouard Sax pavillon pivotant | |

| c. 1900 | 4 piston valves | Musée de la Musique, Paris | Adolphe-Edouard Sax pavillon tournant | |

References

Bibliography

- Bevan, Clifford (1990). "The Saxtuba and Organological Vituperation". The Galpin Society Journal (Galpin Society) 43: pp. 135–146. doi:10.2307/842482. ISSN 0072-0127. JSTOR 842482. OCLC 52966757.

- Carter, Stewart (1999). Brass Scholarship in Review. Paris: Pendragon Press. ISBN 978-1-57647-105-0.

- Forsyth, Cecil (1914). Orchestration. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-486-24383-2.

- Haine, Malou (1980). Adolphe Sax (1814–1894): sa vie, son oeuvre et ses instruments de musique. Brussels: Éditions de l'Université de Bruxelles. ISBN 978-2-8004-0711-1.

Notes

- ↑ Clifford Bevan (1990) gives the instrument's name as Saxtuba throughout. Other sources refer to the Sax-tuba or saxo-tuba.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster: Saxtuba.

- ↑ Bevan (1990), p. 136. The buccin of 1791 should not be confused with a slightly later instrument of the same name (buccin), which was a species of trombone.

- ↑ Haine (1980), p. 57. Sax set up his first workshop at 10 Rue Neuve-Saint-Georges in July 1843.

- ↑ Brevet d'invention 8351. The patent was amended on 20 August 1849 and again on 23 April 1852; the latter, significantly, was the date of the première of Le Juif errant. According to Haine (1980), pp. 196–197, Sax's two amendments were granted on 5 December 1849 (by which date Sax had moved his atelier to No. 50 Rue Saint-Georges) and 30 June 1852 respectively. But see also Bevan (1990), pp. 135 and 137, where the patent number is 4361.

- ↑ This practice is known as lipping. By slightly opening or closing the aperture of the lips, the player can alter the pitch of the note being played.

- ↑ Haine (1980), p. 76.

- ↑ A contemporary account mentions fifteen players in all, as some of the individual parts were played by two, three or four instrumentalists. See Bevan (1990), pp. 138 and 142; and Carter (1999), p. 144.

- ↑ Halévy, Fromental (1852). Le Juif errant. Bibliothèque-Musée de l'Opéra National de Paris. A 576 a I–V.

- ↑ Carter (1999), p. 145. Bevan (1990), pp. 138–139, calls the Triumphal March in the Act III finale "No. 12", and identifies the other appearance of the saxtuba banda as No. 17 in Act IV.

- ↑ Carter (1999), pp. 144 f.

- ↑ Carter (1999), p. 145.

- ↑ Bevan (1990), p. 137; Horwood, Wally (1922). Adolphe Sax: 1814–1894: His Lfe and Legacy. Egon. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4179-0200-2..

- ↑ Carter (1999), p. 137. Haine (1980), p. 98, identifies this instrument as a contrabass saxhorn in B♭.

- ↑ Haine (1980), p. 98.

- ↑ Carter (1999), pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Berlioz, Hector; Richard Strauss (1948). Treatise on Instrumentation. trans. Theodore Front. Kalmus.

These are instruments with cup-formed mouthpieces...."

- ↑ Berlioz, Hector (1856). A treatise Upon Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration. trans. Mary Cowden Clarke. London: Novello, Ewer and Co..

- ↑ Berlioz, Hector (1860-10-01). "New Instruments". The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular (Musical Times Publications) 9 (212): 345–348. doi:10.2307/3370661. JSTOR 3370661..

- ↑ Hubbard, W. L. (1910). The American History and Encyclopedia of Music Dictionary. Toledo: The Squire Cooley Co. p. 454. ISBN 978-1-4179-0200-2.

- ↑ Stanley Sadie, ed. (1984). "Saxtuba". The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments 3. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-943818-05-4. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Bevan (1990), pp. 138–142.

- ↑ Berlioz, Hector (1855). Grand Traité d’Instrumentation et d’Orchestration Modernes. Paris: Schonenberger. p. 234. I am assuming that Halévy's "sax-horn au pistons en Si♭" and "Sax-horn contre Alto en Si♭" are the same instrument.

- ↑ Forsyth (1914) gives these as the natural ranges of the half-tube and whole-tube saxhorns respectively, though he notes that "the top fourth on all three [whole-tube] instruments is a little difficult to get, and not much needed, while on [the Contrabass in B♭] the lowest seven semitones are unsteady and of doubtful intonation". Forsyth does not mention the saxtuba itself.

- ↑ Haine (1980), pp. 74 and 76. Haine dates this innovation to both 1859 and 1881, the latter being the year in which Sax patented his system of independent valves.

- ↑ Mitroulia, Eugenia; Myers, Arnold (2008). "List of Adolphe Sax Instruments". Retrieved 2008-11-18.. According to Bevan (1990), p. 137, the first item in the table is the only saxtuba still in existence.