Satisfiability modulo theories

In computer science and mathematical logic, the satisfiability modulo theories (SMT) problem is a decision problem for logical formulas with respect to combinations of background theories expressed in classical first-order logic with equality. Examples of theories typically used in computer science are the theory of real numbers, the theory of integers, and the theories of various data structures such as lists, arrays, bit vectors and so on. SMT can be thought of as a form of the constraint satisfaction problem and thus a certain formalized approach to constraint programming.

Basic terminology

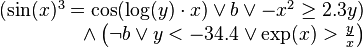

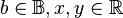

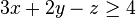

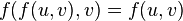

Formally speaking, an SMT instance is a formula in first-order logic, where some function and predicate symbols have additional interpretations, and SMT is the problem of determining whether such a formula is satisfiable. In other words, imagine an instance of the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT) in which some of the binary variables are replaced by predicates over a suitable set of non-binary variables. A predicate is basically a binary-valued function of non-binary variables. Example predicates include linear inequalities (e.g.,  ) or equalities involving uninterpreted terms and function symbols (e.g.,

) or equalities involving uninterpreted terms and function symbols (e.g.,  where

where  is some unspecified function of two unspecified arguments.) These predicates are classified according to each respective theory assigned. For instance, linear inequalities over real variables are evaluated using the rules of the theory of linear real arithmetic, whereas predicates involving uninterpreted terms and function symbols are evaluated using the rules of the theory of uninterpreted functions with equality (sometimes referred to as the empty theory). Other theories include the theories of arrays and list structures (useful for modeling and verifying software programs), and the theory of bit vectors (useful in modeling and verifying hardware designs). Subtheories are also possible: for example, difference logic is a sub-theory of linear arithmetic in which each inequality is restricted to have the form

is some unspecified function of two unspecified arguments.) These predicates are classified according to each respective theory assigned. For instance, linear inequalities over real variables are evaluated using the rules of the theory of linear real arithmetic, whereas predicates involving uninterpreted terms and function symbols are evaluated using the rules of the theory of uninterpreted functions with equality (sometimes referred to as the empty theory). Other theories include the theories of arrays and list structures (useful for modeling and verifying software programs), and the theory of bit vectors (useful in modeling and verifying hardware designs). Subtheories are also possible: for example, difference logic is a sub-theory of linear arithmetic in which each inequality is restricted to have the form  for variables

for variables  and

and  and constant

and constant  .

.

Most SMT solvers support only quantifier free fragments of their logics.

Expressive power of SMT

An SMT instance is a generalization of a Boolean SAT instance in which various sets of variables are replaced by predicates from a variety of underlying theories. Obviously, SMT formulas provide a much richer modeling language than is possible with Boolean SAT formulas. For example, an SMT formula allows us to model the datapath operations of a microprocessor at the word rather than the bit level.

By comparison, answer set programming is also based on predicates (more precisely, on atomic sentences created from atomic formula). Unlike SMT, answer-set programs do not have quantifiers, and cannot easily express constraints such as linear arithmetic or difference logic—ASP is at best suitable for boolean problems that reduce to the free theory of uninterpreted functions. Implementing 32-bit integers as bitvectors in ASP suffers from most of the same problems that early SMT solvers faced: "obvious" identities such as x+y=y+x are difficult to deduce.

Constraint logic programming does provide support for linear arithmetic constraints, but within a completely different theoretical framework.

SMT solver approaches

Early attempts for solving SMT instances involved translating them to Boolean SAT instances (e.g., a 32-bit integer variable would be encoded by 32 bit variables with appropriate weights and word-level operations such as 'plus' would be replaced by lower-level logic operations on the bits) and passing this formula to a Boolean SAT solver. This approach, which is referred to as the eager approach, has its merits: by pre-processing the SMT formula into an equivalent Boolean SAT formula we can use existing Boolean SAT solvers "as-is" and leverage their performance and capacity improvements over time. On the other hand, the loss of the high-level semantics of the underlying theories means that the Boolean SAT solver has to work a lot harder than necessary to discover "obvious" facts (such as  for integer addition.) This observation led to the development of a number of SMT solvers that tightly integrate the Boolean reasoning of a DPLL-style search with theory-specific solvers (T-solvers) that handle conjunctions (ANDs) of predicates from a given theory. This approach is referred to as the lazy approach.

for integer addition.) This observation led to the development of a number of SMT solvers that tightly integrate the Boolean reasoning of a DPLL-style search with theory-specific solvers (T-solvers) that handle conjunctions (ANDs) of predicates from a given theory. This approach is referred to as the lazy approach.

Dubbed DPLL(T),[1] this architecture gives the responsibility of Boolean reasoning to the DPLL-based SAT solver which, in turn, interacts with a solver for theory T through a well-defined interface. The theory solver need only worry about checking the feasibility of conjunctions of theory predicates passed on to it from the SAT solver as it explores the Boolean search space of the formula. For this integration to work well, however, the theory solver must be able to participate in propagation and conflict analysis, i.e., it must be able to infer new facts from already established facts, as well as to supply succinct explanations of infeasibility when theory conflicts arise. In other words, the theory solver must be incremental and backtrackable.

SMT for undecidable theories

Most of the common SMT approaches support decidable theories. However, many real-world systems can only be modelled by means of non-linear arithmetic over the real numbers involving transcendental functions, e.g. an aircraft and its behavior. This fact motivates an extension of the SMT problem to non-linear theories, e.g. determine whether

where

is satisfiable. Then, such problems become undecidable in general. (It is important to note, however, that the theory of real closed fields, and thus the full first order theory of the real numbers, are decidable using quantifier elimination. This is due to Alfred Tarski.) The first order theory of the natural numbers with addition (but not multiplication), called Presburger arithmetic, is also decidable. Since multiplication by constants can be implemented as nested additions, the arithmetic in many computer programs can be expressed using Presburger arithmetic, resulting in decidable formulas.

Examples of SMT solvers addressing Boolean combinations of theory atoms from undecidable arithmetic theories over the reals are ABsolver,[2] which employs a classical DPLL(T) architecture with a non-linear optimization packet as (necessarily incomplete) subordinate theory solver, and iSAT , building on a unification of DPLL SAT-solving and interval constraint propagation called the iSAT algorithm.[3]

SMT solvers

The table below summarizes some of the features of the many available SMT solvers. The column "SMT-LIB" indicates compatibility with the SMT-LIB language; many systems marked 'yes' may support only older versions of SMT-LIB, or offer only partial support for the language. The column "CVC" indicates support for the CVC language. The column "DIMACS" indicates support for the DIMACS format.

Projects differ not only in features and performance, but also in the viability of the surrounding community, its ongoing interest in a project, and its ability to contribute documentation, fixes, tests and enhancements.

| Platform | Features | Notes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | OS | License | SMT-LIB | CVC | DIMACS | Built-in theories | API | SMT-COMP | |

| ABsolver | Linux | CPL | v1.2 | No | Yes | linear arithmetic, non-linear arithmetic | C++ | no | DPLL-based |

| Alt-Ergo | Linux, Mac OS, Windows | CeCILL-C (roughly equivalent to LGPL) | partial v1.2 and v2.0 | No | No | empty theory, linear integer and rational arithmetic, non-linear arithmetic, polymorphic arrays, enumerated datatypes, AC symbols, bitvectors, record datatypes, quantifiers | OCaml | 2008 | Polymorphic first-order input language à la ML, SAT-solver based, combines Shostak-like and Nelson-Oppen like approaches for reasoning modulo theories |

| Barcelogic | Linux | Proprietary | v1.2 | empty theory, difference logic | C++ | 2009 | DPLL-based, congruence closure | ||

| Beaver | Linux, Windows | BSD | v1.2 | No | No | bitvectors | OCaml | 2009 | SAT-solver based |

| Boolector | Linux | GPLv3 | v1.2 | No | No | bitvectors, arrays | C | 2009 | SAT-solver based |

| CVC3 | Linux | BSD | v1.2 | Yes | empty theory, linear arithmetic, arrays, tuples, types, records, bitvectors, quantifiers | C/C++ | 2010 | proof output to HOL | |

| CVC4 | Linux, Mac OS, Windows | BSD | Yes | Yes | rational and integer linear arithmetic, arrays, tuples, records, inductive data types, bit-vectors, strings, and equality over uninterpreted function symbols | C++ | 2010 | version 1.4 released July 2014 | |

| Decision Procedure Toolkit (DPT) | Linux | Apache | No | OCaml | no | DPLL-based | |||

| iSAT | Linux | Proprietary | No | non-linear arithmetic | no | DPLL-based | |||

| MathSAT | Linux | Proprietary | Yes | Yes | empty theory, linear arithmetic, bitvectors, arrays | C/C++, Python, Java | 2010 | DPLL-based | |

| MiniSmt | Linux | LGPL | partial v2.0 | non-linear arithmetic | 2010 | SAT-solver based, Yices-based | |||

| OpenCog | Linux | AGPL | No | No | No | probabilistic logic, arithmetic. relational models | C++, Scheme, Python | no | subgraph isomorphism |

| OpenSMT | Linux, Mac OS, Windows | GPLv3 | partial v2.0 | Yes | empty theory, differences, linear arithmetic, bitvectors | C++ | 2011 | lazy SMT Solver | |

| SatEEn | ? | Proprietary | v1.2 | linear arithmetic, difference logic | none | 2009 | |||

| SMTInterpol | Linux, Mac OS, Windows | LGPLv3 | v2.0 | uninterpreted functions, linear real arithmetic, and linear integer arithmetic | Java | 2012 | Focuses on generating high quality, compact interpolants. | ||

| SMCHR | Linux, Mac OS, Windows | GPLv3 | No | No | No | linear arithmetic, nonlinear arithmetic, heaps | C | no | Can implement new theories using Constraint Handling Rules. |

| SMT-RAT | Linux, Mac OS | GPLv3 | v2.0 | No | No | linear arithmetic, nonlinear arithmetic | C++ | no | Toolbox offering theory solver modules for the development of SMT solvers for nonlinear real arithmetic (NRA). Example embedding in OpenSMT available. |

| SONOLAR | Linux, Windows | Proprietary | partial v2.0 | bitvectors | C | 2010 | SAT-solver based | ||

| Spear | Linux, Mac OS, Windows | Proprietary | v1.2 | bitvectors | 2008 | ||||

| STP | Linux, OpenBSD, Windows, Mac OS | MIT | partial v2.0 | Yes | No | bitvectors, arrays | C, C++, Python, OCaml, Java | 2011 | SAT-solver based |

| SWORD | Linux | Proprietary | v1.2 | bitvectors | 2009 | ||||

| UCLID | Linux | BSD | No | No | No | empty theory, linear arithmetic, bitvectors, and constrained lambda (arrays, memories, cache, etc.) | no | SAT-solver based, written in Moscow ML. Input language is SMV model checker. Well-documented! | |

| veriT | Linux, OS X | BSD | partial v2.0 | empty theory, rational and integer linear arithmetics, quantifiers, and equality over uninterpreted function symbols | C/C++ | 2010 | SAT-solver based | ||

| Yices | Linux, Mac OS, Windows | Proprietary | v2.0 | No | Yes | rational and integer linear arithmetic, bit-vectors, arrays, and equality over uninterpreted function symbols | C | 2014 | Source code is available online |

| Z3 | Linux, Mac OS, Windows, FreeBSD | MIT | v2.0 | Yes | empty theory, linear arithmetic, nonlinear arithmetic, bitvectors, arrays, datatypes, quantifiers | C/C++, .NET, OCaml, Python, Java | 2011 | ||

Applications

SMT solvers are useful both for verification, proving the correctness of programs, software testing based on symbolic execution, and for synthesis, generating program fragments by searching over the space of possible programs.

Verification

Computer-aided verification of software programs often uses SMT solvers. A common technique is to translate preconditions, postconditions, loop conditions, and assertions into SMT formulas in order to determine if all properties can hold.

There are many verifiers built on top of the Z3 SMT solver. Boogie is an intermediate verification language that uses Z3 to automatically check simple imperative programs. The verifier for concurrent C uses Boogie, as well as Dafny for imperative object-based programs, Chalice for concurrent programs, and Spec# for C#. F* is a dependently typed language that uses Z3 to find proofs; the compiler carries these proofs through to produce proof-carrying bytecode.

There are also many verifiers built on top of the Alt-Ergo SMT solver. Here is a list of mature applications:

- Why3, a platform for deductive program verification, uses Alt-Ergo as its main prover;

- CAVEAT, a C-verifier developed by CEA and used by Airbus; Alt-Ergo was included in the qualification DO-178C of one of its recent aircraft;

- Frama-C, a framework to analyse C-code, uses Alt-Ergo in the Jessie and WP plugins (dedicated to "deductive program verification");

- SPARK, uses Alt-Ergo (behind GNATprove) to automate the verification of some assertions in Spark 2014;

- Atelier-B can use Alt-Ergo instead of its main prover (increasing success from 84% to 98% on the ANR Bware project benchmarks);

- Rodin, a B-method framework developed by Systerel, can use Alt-Ergo as a back-end;

- Cubicle, an open source model checker for verifying safety properties of array-based transtion systems.

- EasyCrypt, a toolset for reasoning about relational properties of probabilistic computations with adversarial code.

Many SMT solvers implement a common interface format called SMTLIB2. The LiquidHaskell tool implements a refinement type based verifier for Haskell that can use any SMTLIB2 compliant solver, e.g. CVC4, MathSat, or Z3.

Symbolic-execution based analysis and testing

An important class of applications for SMT solvers is symbolic-execution based analysis and testing of programs (e.g., concolic testing), aimed particularly at finding security vulnerabilities. Important actively-maintained tools in this category include SAGE from Microsoft Research, KLEE, and S2E. SMT solvers that are particularly useful for symbolic-execution applications include Z3, STP, Z3str2, and Boolector.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Nieuwenhuis, R.; Oliveras, A.; Tinelli, C. (2006), "Solving SAT and SAT Modulo Theories: From an Abstract Davis-Putnam-Logemann-Loveland Procedure to DPLL(T)", Journal of the ACM (PDF) 53 (6), pp. 937–977.

- ↑ Bauer, A.; Pister, M.; Tautschnig, M. (2007), "Tool-support for the analysis of hybrid systems and models", Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Design, Automation and Test in Europe (DATE'07), IEEE Computer Society, p. 1, doi:10.1109/DATE.2007.364411

- ↑ Fränzle, M.; Herde, C.; Ratschan, S.; Schubert, T.; Teige, T. (2007), "Efficient Solving of Large Non-linear Arithmetic Constraint Systems with Complex Boolean Structure", JSAT Special Issue on SAT/CP Integration (PDF) 1, pp. 209–236

References

- Vijay Ganesh (PhD. Thesis 2007), Decision Procedures for Bit-Vectors, Arrays and Integers, Computer Science Department, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, U.S., Sept 2007

- Susmit Jha, Rhishikesh Limaye, and Sanjit A. Seshia. Beaver: Engineering an efficient SMT solver for bit-vector arithmetic. In Proceedings of 21st International Conference on Computer-Aided Verification, pp. 668–674, 2009.

- R. E. Bryant, S. M. German, and M. N. Velev, "Microprocessor Verification Using Efficient Decision Procedures for a Logic of Equality with Uninterpreted Functions," in Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods, pp. 1–13, 1999.

- M. Davis and H. Putnam, A Computing Procedure for Quantification Theory, Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery, vol. 7, no., pp. 201–215, 1960.

- M. Davis, G. Logemann, and D. Loveland, A Machine Program for Theorem-Proving, Communications of the ACM, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 394–397, 1962.

- D. Kroening and O. Strichman, Decision Procedures – an algorithmic point of view (2008), Springer (Theoretical Computer Science series) ISBN 978-3-540-74104-6.

- G.-J. Nam, K. A. Sakallah, and R. Rutenbar, A New FPGA Detailed Routing Approach via Search-Based Boolean Satisfiability, IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 674–684, 2002.

- SMT-LIB: The Satisfiability Modulo Theories Library

- SMT-COMP: The Satisfiability Modulo Theories Competition

- Decision procedures - an algorithmic point of view

- Summer School on SAT/SMT solvers and their applications

- Satisfiability Modulo Theories: A Pragmatic Introduction (basic lectures with OpenSMT)

This article is adapted from a column in the ACM SIGDA e-newsletter by Prof. Karem Sakallah. Original text is available here