Sarmatism

.jpg)

"Sarmatism" (also, "Sarmatianism") is a term designating the dominant lifestyle, culture and ideology of the szlachta (nobility) of the Kingdom of Poland and later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from the 15th to the 18th centuries. Together with "Golden Liberty," it formed a central aspect of the Commonwealth's culture. At its core was the belief that Polish nobles were descended from the ancient Sarmatians.[1][2] It has been celebrated by adherents as well as sharply criticized.

The term and culture were reflected primarily in 17th-century Polish literature, as in Jan Chryzostom Pasek's memoirs,[3] and the poems of Wacław Potocki. The Polish gentry (szlachta) wore a long coat trimmed with fur, called a żupan, thigh-high boots, and carried a saber (szabla). Mustaches were also popular, as well as varieties of plumage in the menfolk's headgear. Poland's "Sarmatians" strove for the status of a nobility on horseback, for equality among themselves ("Golden Freedom"), and for invincibility in the face of other peoples.[4] Sarmatism lauded the past victories of the Polish Army, and required Polish noblemen to cultivate the tradition. An inseparable element of their festive costume was a saber called the karabela.

Sarmatia (in Polish, Sarmacja) was a semi-legendary, poetic name for Poland that was fashionable into the 18th century, and which designated qualities associated with the literate citizenry of the vast Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Sarmatism greatly affected the culture, lifestyle and ideology of the Polish nobility. It was unique for its cultural mix of Eastern, Western and native traditions. Sarmatism considerably influenced the noble cultures of other contemporary states — Ukraine, Moldavia, Transylvania, Serbian Despotate, Habsburg Hungary and Croatia, Wallachia and Muscovy. Criticized during the Polish Enlightenment, Sarmatism was rehabilitated by the generations that embraced Polish Romanticism. Having survived the literary realism of Poland's "Positivist" period, Sarmatism enjoyed a triumphant comeback with The Trilogy of Henryk Sienkiewicz, Poland's first Nobel laureate in literature (1905).

Late medieval origin, links to ancient history

The term Sarmatism was first used by Jan Długosz in his 15th century work on the history of Poland.[5] Długosz was also responsible for linking the Sarmatians to the prehistory of Poland and this idea was continued by other chroniclers and historians such as Marcin Bielski, Marcin Kromer, and Maciej Miechowita.[5] Miechowita's Tractatus de Duabus Sarmatiis became influential abroad, where for some time it was one of the most widely used reference works on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[5]

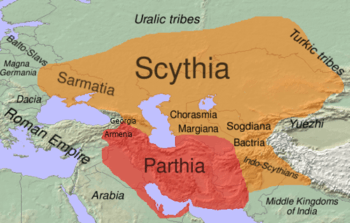

The presumed ancestors of the szlachta, the Sarmatians, were a confederacy of predominantly Iranian tribes living north of the Black Sea. In the 5th century BC Herodotus wrote that these tribes were descendants of the Scythians and Amazons. The Sarmatians were infiltrated by the Goths and others in the 2nd century AD, and may have had some strong and direct links to Poland. Yet such issues are not simple.[6] The legend stuck and grew until most of those within the Commonwealth, and many abroad, believed that many Polish nobles were somehow descendants of the Sarmatians (Sauromates).[5] Another tradition came to surmise that the Sarmatians themselves were descended from Japheth, son of Noah.[7]

Some holding to Sarmatism tended to believe that as medieval Polish nobility they were the descendents of the ancient Sarmatian people. Accordingly their ancestors would have conquered and enserfed the local Slavs and, like the Bulgars in Bulgaria or Franks who conquered Gaul (France), eventually adopted the local language. Such nobility might believe that they belonged (at least figuratively) to a different people (however remote and long ago) than the Slavs whom they ruled. One view would see in Sarmatism much that was "low brow" or uneducated in origin. "Roman maps, fashioned during the Renaissance, had the name of Sarmatia written over most of the territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and thus 'justified' interest in 'Sarmatian roots'."[8]

Centuries later modern scholarship discovered evidence showing that the Alans, a late Sarmatian people speaking an Iranian idiom, did invade Slavic tribes in Eastern Europe before the sixth century, and that these "Sarmatians evidently formed the area's ruling class, which was gradually Slavicized."[9] Their direct political connection to Poland, however, would remain somewhat uncertain.[10] In his 1970 publication The Sarmatians (in the series "Ancient Peoples and Places") Tadeusz Sulimirski (1898–1983), a Polish-British historian, archaeologist, and researcher on the ancient Sarmatians, discusses the abundant evidence of the ancient Sarmatian presence in Eastern Europe, e.g., the finds of various grave goods such as pottery, weapons, and jewelry. Possible ethnological and social influences on the Polish szlachta would include tamga-inspired heraldry, social organization, military practices, and burial customs.[11]

Culture and fashion

Sarmatian belief and customs became an important part of szlachta culture, penetrating all aspects of life. Sarmatism enshrined equality among all szlachta, and celebrated their life style and traditions, including horseback riding, provincial village life, peace and relative pacifism,[12] It popularised Eastern (almost oriental) clothing and looks, such as the żupan, kontusz, sukmana, pas kontuszowy, delia, and szabla. Thereby it served to integrate the multiethnic nobility by creating an almost nationalist sense of unity and pride in the szlachta's political Golden Freedoms. It also differentiated the Polish szlachta from Western nobility (which szlachta called pludracy, a reference to their hose, an item of clothing not worn by the szlachta but popular among Westerners).

Sarmatians strongly valued social and family ties. Women were treated with honour and gallantry. Conversations were one of the favourite preoccupations. Guests were always welcomed – relatives, friends, even strangers, especially from abroad. Latin was widely spoken. Sumptuous feasts with large amount of alcohol were organised. Male quarrels and fighting during such events were quite common. At their parties the polonaise, mazurka, and oberek were the most popular dances. Honour was of prime relevance. Men lived longer than women; they also married later. Marriage was described as ‘deep friendship’. Men often travelled a lot (to the Sejms, Sejmiki, indulgences, law courts, or common movements). Women stayed at home and took care of the property, livestock and children. Although large numbers of children were born, many of them died before reaching maturity. Girls and boys were brought up separately, either in the company of women or men. Suing, even for relatively irrelevant matters, was common, but in most cases a compromise was reached.

Funeral ceremonies in Sarmatian Poland were very elaborate, with some distinctive features compared to other parts of Europe. They were carefully planned events, full of ceremony and splendour. Elaborate preparations were made in the period between a nobleman’s death and his funeral, which employed a large number of craftsmen, architects, decorators, servants and cooks. Sometimes many months passed before all the preparations were completed. Before the burial, the coffin with the corpse was placed in a church amid the elaborate architecture of the castrum doloris ("castle of mourning"). Heraldic shields, which were placed on the sides of the coffin, and a tin sheet with an epitaph served a supplementary role and provided information about the deceased person. Religious celebrations were usually preceded by a procession which ended in the church. It was led by a horseman who played the role of the deceased nobleman and wore his armour. This horseman would enter the church and fall off his horse with a tremendous bang and clank, showing in this way the triumph of death over earthly might and knightly valour. Some funeral ceremonies lasted for as long as four days, ending with a wake which had little to do with the seriousness of the situation, and could easily turn into sheer revelry. Occasionally an army of clergy took part in the burial (in the 18th century, 10 bishops, 60 canons and 1705 priests took part in the funeral of one Polish nobleman).

Some Polish nobles felt that their supposed Sarmatian ancestors were a Turkic people and accordingly viewed their Turkish and Crimean Tatar enemies as peers, albeit ones who were unredeeemed because they were not Christians. Many Sarmatians believed that the Slavs whom they ruled (whether Polish-speaking Roman Catholic or Ruthenian-speaking Orthodox) were backward. This ideology placed the Polish followers of Sarmatism at odds with the later Russian pan-Slavists. [13] Commonwealth armies during this period, of course, were regularly at war with the Ottoman Empire; any military advantages demonstrated by their foes, the Poles naturally copied. Also, during the Baroque era in Poland, the art and furnishings of the Persians and the Chinese, as well as the Ottomans, were admired and displayed.[14]

In accordance with their views on their supposed Turkic origins,[13] Sarmatian costume stood out from that worn by the noblemen of other European countries, and had its roots in the Orient. It was long, dignified, rich and colourful. One of its most characteristic elements was the kontusz, which was worn with the decorative kontusz belt. Underneath, the żupan was worn, and over the żupan the delia. Clothes for the mightiest families were crimson and scarlet. The szarawary were typical lower-body clothing, and the calpac, decorated with heron’s feathers, was worn on the head. French fashions, however, also contributed to the Sarmatian look in Polish attire.[15]

Political thought and institutions

Adherents of Sarmatism acknowledged the vital importance of Poland since it was considered an oasis of the Golden Liberty for Polish nobility, otherwise surrounded by antagonistic realms with absolutist governments. They also viewed Poland as the bulwark of true Christendom, almost surrounded by the Muslim Ottoman Empire, and by the errant Christianity of the Orthodox Russians and the Protestant Germans and Swedes.

What contemporary Polish historians consider to be one of the most essential features of this tradition is not Sarmatian ideology but the manner in which the Rzeczpospolita was governed. The democratic concepts of law and order, self-government and elective offices constituted an inseparable part of Sarmatism. Yet it was democracy only for the few. The king, though elected, still held the central position in the state, but his power was limited by various legal acts and requirements. Moreover, only the nobles were given political rights, namely the vote in the Sejmik and the Sejm. Every poseł (or member of the Sejm), had the right to exercise a so-called liberum veto, which could block the passage of a proposed new resolution or law. Finally, in the event that the king failed to abide by the laws of the state, or tried to limit or question nobles’ privileges, they had the right to refuse the king’s commands, and to oppose him by force of arms. Although thus avoiding absolutist rule, unfortunately the central state power became precarious, and vulnerable to anarchy.[16]

The political system of the Rzeczpospolita was regarded by the nobility as the best in the world, and the Polish Sejm as (factually[17]) the oldest. The system was frequently compared to Republican Rome and to the Greek polis – though each of these eventually surrendered to imperial rule or to tyrants. The Henrician Articles were considered to be the foundation of the system. Every attempt to infringe on these laws was treated as a great crime.

Yet despite fruits of golden age Poland and the Sarmatian culture, the country would enter a period of national decline; it brought in a narrow cultural conformity.[18] Nonetheless, a crippling political anarchy came to reign, due to cynical use of the free veto by individual szlachta in the Sejm,[19] and/or to the acts of unpatriotic kings.[20] During the late eighteenth century, the woeful state of the polity resulted in the three Polish Partitions by neighboring military powers.

"Was the Sarmatian way of life worth preserving? Some aspects of it, no doubt. But because the gentry insisted on jealously guarding its privileges, preventing their extension to other social groups, it doomed the structure of the Commonwealth to atrophy and to the revenge of the lower orders. ... Sarmatism was an ideological shield against the historical realities which contradicted it at every turn."[21]

Since its original popularity among the former szlachta, Sarmatism itself went into political decline, but has since seen revision and revival, and then eclipse.

Religion

“Certainly, the wording and substance of the declaration of the Confederation of Warsaw of 28 January 1573 were extraordinary with regard to prevailing conditions elsewhere in Europe, and they governed the principles of religious life in the Republic for over two hundred years.” – Norman Davies[22]

Poland has a long tradition of religious freedom. The right to worship freely was a basic right given to all inhabitants of the Commonwealth throughout the 15th and early 16th centuries, and complete freedom of religion was officially recognized in Poland in 1573 during the Warsaw Confederation. Poland maintained its religious freedom laws during an era when religious persecution was an everyday occurrence in the rest of Europe.[23] The Commonwealth of Poland was a place where the most radical religious sects, trying to escape persecution in other countries of the Christian world, sought refuge.[24]

"This country became a place of shelter for heretics” – Cardinal Hozjusz papal legate to Poland.[25]

In the sphere of religion, Catholicism was the dominant faith and heavily emphasized because it was seen as differentiating the Polish Sarmatians from their Turkish and Tatar peers.[13] Providence and the grace of God were often emphasized. All earthly matters were perceived as a means to a final goal – Heaven. Penance was stressed as a means of saving oneself from eternal punishment. It was believed that God watches over everything and everything has its meaning. People willingly took part in religious life: masses, indulgences and pilgrimages. Special devotion was paid to Saint Mary, the saints and the Passion.

Sarmatian art and writings

Art was treated by Sarmatians as propagandistic in function: its role was to immortalise a good name for the family, extolling the virtues of ancestors and their great deeds. Consequently, personal or family portraits were in great demand. Their characteristic features were realism, variety of colour and rich symbolism (epitaphs, coats of arms, military accessories). People were usually depicted against a subdued, dark background, in a three-quarter view.

Sarmatian culture was portrayed especially by:

- Wacław Potocki

- Jan Chryzostom Pasek

- Wespazjan Kochowski

- Andrzej Zbylitowski

- Hieronim Morsztyn

- Jan Andrzej Morsztyn

- Daniel Naborowski

- Justus Ludwik Decjusz

Latin was very popular and often mixed with the Polish language in macaronic writings and in speech. Knowing at least some Latin was an obligation for any szlachcic.

In the 19th century the Sarmatist culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was portrayed and popularised by Henryk Sienkiewicz in his trilogy (Ogniem i Mieczem, Potop, Pan Wolodyjowski). In the 20th century, Sienkiewicz's trilogy was filmed, and Sarmatian culture became the subject of many modern books (by Jacek Komuda and others), songs (like that of Jacek Kaczmarski) and even role-playing games like Dzikie Pola.

One of the most distinctive art forms of the Sarmatians were the coffin portraits, a form of portraiture characteristic of Polish Baroque painting, not to be found anywhere else in Europe. The octagonal or hexagonal portraits were fixed to the headpiece of the coffin so that the deceased person, being a Christian with an immortal soul, was always represented as alive and capable of holding a dialogue with mourners during lavish funeral celebrations. Such portraits were props which evoked the illusion of the dead person's presence, and also a ritual medium that provided a link between the living and those departing for eternity. The few surviving portraits, often painted during a person’s lifetime, are a dependable source of information about 17th-century Polish nobility. The dead were depicted either in their official clothes or in travelling garb, since death was believed to be a journey into the unknown. The oldest known coffin portrait in Poland is that depicting Stefan Batory, dating from the end of the 16th century.

Many of the szlachta residences were wooden mansions[26] Numerous palaces and churches were built in Sarmatian Poland. There was a trend towards native architectural solutions which were characterised by Gothic forms and unique stucco ornamentation of vaults. Gravestones were erected in churches for those who had rendered considerable services for the motherland. Tens of thousands of manor houses were built, the majority of wood (pine, fir and larch). At the entrance there was a porch. The central place where visitors were received was a large entrance hall. In the manor house there was an intimate part for women, and a more public one for men. Manor houses often had corner annexes. Walls were adorned with portraits of ancestors, mementoes and spoils. Few of the manor houses from the Old Polish period have survived, but their tradition was continued in the 19th and 20th century.

Modern usage

In contemporary Poland, the word "Sarmatian" (Polish: Sarmata- when used as noun, sarmacki- when used as adjective) is a form of ironic self-identification, and is sometimes used as a synonym for the Polish character.

A scholarly journal on Poland, central and eastern Europe, has recently been launched by Polish-Americans, published at Rice University and called the Sarmatian Review.

In contemporary Lithuanian language, the word "sarmata" has positive meaning. It means propriety, sense of shame. "Besarmatis" is an adjective which literally means "someone without sarmata," i.e. a person with no sense of shame, usually someone who is dressed or behaving in a scandalous, improper way.

Impact on other peoples within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Lithuanians and Ukrainians living within the Commonwealth also adopted certain aspects of Sarmatism. Some Lithuanian historians of that time claimed that their people were descended from Scythians who had settled in ancient Rome, which had become the home of their pagan high priest.[13]

Ukrainians of that time claimed descent from Sarmatians or a related tribe, the Roxolani. They also claimed descent from the Turkic Khazars. For example, the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk of 1711 (also known as Bender Constitution) included the following declarations: "the valiant and ancient Cossack people, formerly called Khazar, was at first exalted by immortal glory...so much so that the Eastern Emperor...joined his son in matrimony to the daughter of the Khagan, that is to say, the Cossack prince"; "...the Orthodox faith of the Eastern confession, with which the valiant Cossack people was enlightened under the rule of Khazar princes by the Apostolic See of Constantinople..."; "whereas the people formerly known as the Khazars and later called Cossacks trace their genealogical origin to the powerful and invincible Goths...and join together that Cossack people by the deepest ties of affectionate affinity to the Crimean state...". [13]

Tatars who had settled in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and were loyal to the Polish state were viewed by Polish followers of Sarmatism as peers. Accordingly, they enjoyed the privileges of Polish nobility and freedom to practice their Muslim faith. These Tatars, in spite of their Muslim faith, were more easily accepted into Polish society than were Orthodox Christian Ukrainians whose supposed Sarmatian origins were more questionable.[13]

Evaluation

Some have criticised the development of Sarmatism, saying that while it initially supported religious belief, national pride, equality and freedom, over time this was perverted into a form of beliefs conducive to intolerance and fanaticism.

Sarmatism, which evolved during the Polish Renaissance and entrenched itself during the Polish baroque, found itself opposed to the ideology of the Polish Enlightenment. By the late 18th century the word 'Sarmatism' had gained negative associations[5] and the concept was frequently criticized and ridiculed in political publications such as Monitor, where it became a synonym for uneducated and unenlightened ideas and a derogatory term for those who opposed the reforms of the 'progressives' such as the king, Stanisław August Poniatowski.[5] The ideology of Sarmatism became a target for ridicule, as seen in Franciszek Zabłocki's play "Sarmatism" (Sarmatyzm, 1785).[5]

To a certain degree the process was reversed during the period of Polish Romanticism, when after the partitions of Poland memory of the old Polish Golden Age rehabilitated old traditions to a certain extent.[5] Particularly in the aftermath of the November Uprising, when the genre of gawęda szlachecka ("a nobleman's tale") created by Henryk Rzewuski gained popularity, Sarmatism was often portrayed positively in literature.[5] Such treatment of the concept can also be seen in Polish messianism and in works of great Polish poets like Adam Mickiewicz (Pan Tadeusz), Juliusz Słowacki and Zygmunt Krasiński, as well as writers (Henryk Sienkiewicz and his Trylogia), as well as others.[5] This close connection between Polish Romanticism and Polish history became one of the defining qualities of this literary period, differentiating it from other contemporary literature, which did not suffer from a lack of national statehood as was the case with Poland.[5]

See also

- Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth#Culture

- Szlachta#Szlachta culture

Notes

- ↑ Tadeusz Sulimirski, The Sarmatians (New York: Praeger Publishers 1970) at 167.

- ↑ P. M. Barford, The Early Slavs (Ithaca: Cornell University 2001) at 28.

- ↑ Pamiętniki Jana Chryzostoma Paska [1690s] (Poznan 1836), translated by C. S. Leach as 'Memoirs of the Polish Baroque. The Writings of Jan Chryzostom Pasek (University of California 1976).

- ↑ Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory Vintage, New York, 1995:38.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 Andrzej Wasko, Sarmatism or the Enlightenment: The Dilemma of Polish Culture, Sarmatian Review XVII.2.

- ↑ T. Sulimirski, The Sarmatians' (New York: Praeger 1970) at 166–167, 194, 196 (Sarmatian-Polish links). See below.

- ↑ Colin Kidd, British Identities before Nationalism; Ethnicity and Nationhood in the Atlantic World, 1600–1800, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 29

- ↑ Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski, Poland. An illustrated history (New York: Hippocrene 2003) at 73.

- ↑ T. Sulimirski, The Sarmatians (1970) at 26, 196. Sulimirski (at 196n11, 212) footnotes to G. Vernadsky and others.

- ↑ Cf., George Vernadsky, Ancient Russia (New Haven: Yale University 1943) at 78–90, 129–137. "[T]he Alans struck deeper roots in Russia, and entered into closer cooperation with the natives—especially with the Slavs—than any other migratory tribe. It was, as we know, by the Alanic clans that the Slavic tribes of the Antes were organized." Vernadsky (1943) at 135.

- ↑ T. Sulimirski, The Sarmatians' (1970) at 151–155 (Tamghas); at 166–167 (pottery, spears heads, other grave goods; tamgha-inspired heraldry), at 194–196 (jewelry, tribal authority).

- ↑ In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in which the Sejm resisted and vetoed most royal proposals for war; for some examples and discussion, see Frost, Robert I. The northern wars: war, state and society in northeastern Europe, 1558–1721. Harlow, England; New York: Longman's. 2000. Especially Pp. 9–11, 114, 181, 323. See also democratic peace theory.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Dan D.Y. Shapira. (2009) "Turkism", Polish Sarmatism and Jewish Szlachta Some reflections on a cultural context of the Polish-Lithuanian Karaites Karadeniz Arastirmalari pp. 29–43

- ↑ Adam Zamoyski, The Polish Way (New York: Hippocrene 1987) at 163–164 (Black Sea frontier), 187 (1683 Battle of Vienna), 196 (weapons, tactics, insignia); at 198 (the Baroque arts).

- ↑ C. S. Leach, "Introduction" at xliii–xliv, in Memoirs of the Polish Baroque (Berkeley: University of California 1976).

- ↑ Among the urgent reforms then required in Poland were "a stable government, well ordered finances, and an army comparable with that of her neighbors." Oscar Halecki, A History of Poland (New York: Roy 1942; 9th ed., New York: David McKay 1976) at 191.

- ↑ Cronicae et gesta ducum sive principum Polonorum

- ↑ Cf., Oscar Halecki, A History of Poland (New York: Roy 1942; 9th ed., New York: David McKay 1976) at 183–184 (Protestant disabilities).

- ↑ Norman Davies, A History of Poland. Volume I. The Origins to 1795 (New York: Columbia University 1984) at 367.

- ↑ Pawel Jasienica, The Commonwealth of Both Nations (New York: Hippocrene 1987) at 335, 338.

- ↑ Catherine S. Leach, "Introduction" xxvii–lxiv, at xlvii, in Memoirs of the Polish Baroque. The Writings of Jan Chryzostom Pasek, a Squire of the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania (Berkeley: University of California 1976).

- ↑ Norman Davies, God's Playground. A History of Poland, Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795, Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925339-0 / ISBN 0-19-925340-4

- ↑ Zamoyski, Adam. The Polish Way. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1987

- ↑ http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=23126&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

- ↑ http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=23126&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

- ↑ See houses in Poland.

References

- Friedrich, Karin, The other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and liberty, 1569–1772, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Further reading

- Tadeusz Sulimirski, "The Sarmatians (Ancient peoples and places)", Thames and Hudson, 1970, ISBN 0-500-02071-X

External links

- The Sarmatian Review

- Sarmatism or the Enlightenment – The Dilemma of Polish Culture by Andrzej Wasko, Sarmatian Review, April 1997

- Martin Pollack. Sarmatische Landschaften: Nachrichten aus Litauen, Belarus, der Ukraine, Polen und Deutschland (a book of short stories with modern views on Sarmatia, published in 2006 in German language)

- Sarmatism and European Culture at the Wilanów Palace Museum

- The Foundations of Sarmatism. Aurea Libertas and Mores Maiorum at the Wilanów Palace Museum

| ||||||||