Sandwich theory

| Continuum mechanics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

Laws

|

||||

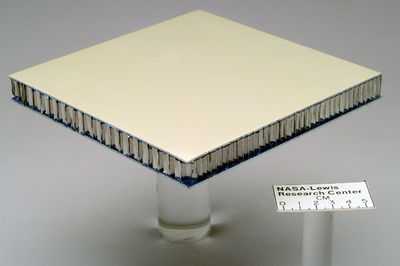

Sandwich theory[1][2] describes the behaviour of a beam, plate, or shell which consists of three layers - two facesheets and one core. The most commonly used sandwich theory is linear and is an extension of first order beam theory. Linear sandwich theory is of importance for the design and analysis of sandwich panels, which are of use in building construction, vehicle construction, airplane construction and refrigeration engineering.

Some advantages of sandwich construction are:

- Sandwich cross sections are composite. They usually consist of a low to moderate stiffness core which is connected with two stiff exterior face-sheets. The composite has a considerably higher shear stiffness to weight ratio than an equivalent beam made of only the core material or the face-sheet material. The composite also has a high tensile strength to weight ratio.

- The high stiffness of the face-sheet leads to a high bending stiffness to weight ratio for the composite.

The behavior of a beam with sandwich cross-section under a load differs from a beam with a constant elastic cross section as can be observed in the adjacent figure. If the radius of curvature during bending is large compared to the thickness of the sandwich beam and the strains in the component materials are small, the deformation of a sandwich composite beam can be separated into two parts

- deformations due to bending moments or bending deformation, and

- deformations due to transverse forces, also called shear deformation.

Sandwich beam, plate, and shell theories usually assume that the reference stress state is one of zero stress. However, during curing, differences of temperature between the face-sheets persist because of the thermal separation by the core material. These temperature differences, coupled with different linear expansions of the face-sheets, can lead to a bending of the sandwich beam in the direction of the warmer face-sheet. If the bending is constrained during the manufacturing process, residual stresses can develop in the components of a sandwich composite. The superposition of a reference stress state on the solutions provided by sandwich theory is possible when the problem is linear. However, when large elastic deformations and rotations are expected, the initial stress state has to be incorporated directly into the sandwich theory.

Engineering sandwich beam theory

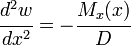

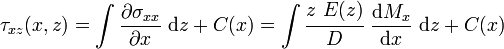

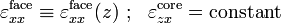

In the engineering theory of sandwich beams,[2] the axial strain is assumed to vary linearly over the cross-section of the beam as in Euler-Bernoulli theory, i.e.,

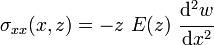

Therefore the axial stress in the sandwich beam is given by

where  is the Young's modulus which is a function of the location along the thickness of the beam. The bending moment in the beam is then given by

is the Young's modulus which is a function of the location along the thickness of the beam. The bending moment in the beam is then given by

The quantity  is called the flexural stiffness of the sandwich beam. The shear force

is called the flexural stiffness of the sandwich beam. The shear force  is defined as

is defined as

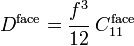

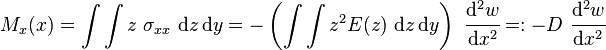

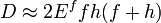

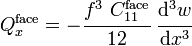

Using these relations, we can show that the stresses in a sandwich beam with a core of thickness  and modulus

and modulus  and two facesheets each of thickness

and two facesheets each of thickness  and modulus

and modulus  , are given by

, are given by

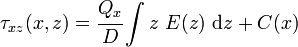

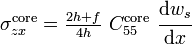

Derivation of engineering sandwich beam stresses Since we can write the axial stress as

The equation of equilibrium for a two-dimensional solid is given by

where

is the shear stress. Therefore,

is the shear stress. Therefore,where

is a constant of integration.

Therefore,

is a constant of integration.

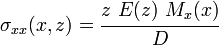

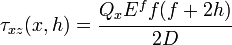

Therefore,Let us assume that there are no shear tractions applied to the top face of the sandwich beam. The shear stress in the top facesheet is given by

At

,

,  implies that

implies that  . Then the shear stress at the top of the core,

. Then the shear stress at the top of the core,  , is given by

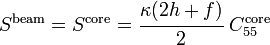

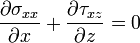

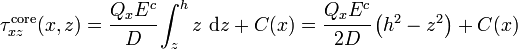

, is given bySimilarly, the shear stress in the core can be calculated as

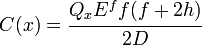

The integration constant

is determined from the continuity of shear stress at the interface of the core and the facesheet. Therefore,

is determined from the continuity of shear stress at the interface of the core and the facesheet. Therefore,and

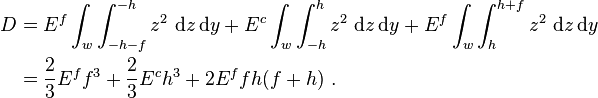

For a sandwich beam with identical facesheets and unit width, the value of  is

is

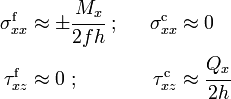

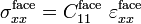

If  , then

, then  can be approximated as

can be approximated as

and the stresses in the sandwich beam can be approximated as

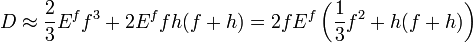

If, in addition,  , then

, then

and the approximate stresses in the beam are

If we assume that the facesheets are thin enough that the stresses may be assumed to be constant through the thickness, we have the approximation

Hence the problem can be split into two parts, one involving only core shear and the other involving only bending stresses in the facesheets.

Linear sandwich theory

Bending of a sandwich beam with thin facesheets

The main assumptions of linear sandwich theories of beams with thin facesheets are:

- the transverse normal stiffness of the core is infinite, i.e., the core thickness in the z-direction does not change during bending

- the in-plane normal stiffness of the core is small compared to that of the facesheets, i.e., the core does not lengthen or compress in the x-direction

- the facesheets behave according to the Euler-Bernoulli assumptions, i.e., there is no xz-shear in the facesheets and the z-direction thickness of the facesheets does not change

However, the xz shear-stresses in the core are not neglected.

Constitutive assumptions

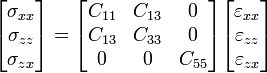

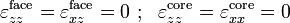

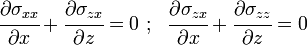

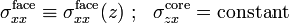

The constitutive relations for two-dimensional orthotropic linear elastic materials are

The assumptions of sandwich theory lead to the simplified relations

and

The equilibrium equations in two dimensions are

The assumptions for a sandwich beam and the equilibrium equation imply that

Therefore, for homogeneous facesheets and core, the strains also have the form

Kinematics

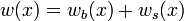

Let the sandwich beam be subjected to a bending moment  and a shear force

and a shear force  . Let the total deflection of the beam due to these loads be

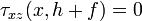

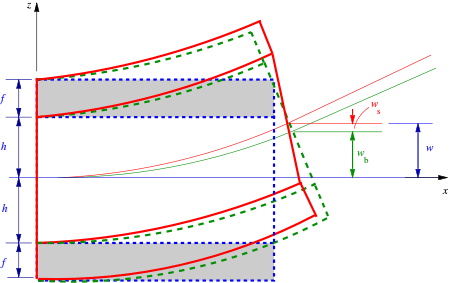

. Let the total deflection of the beam due to these loads be  . The adjacent figure shows that, for small displacements, the total deflection of the mid-surface of the beam can be expressed as the sum of two deflections, a pure bending deflection

. The adjacent figure shows that, for small displacements, the total deflection of the mid-surface of the beam can be expressed as the sum of two deflections, a pure bending deflection  and a pure shear deflection

and a pure shear deflection  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

From the geometry of the deformation we observe that the engineering shear strain ( ) in the core is related the effective shear strain in the composite by the relation

) in the core is related the effective shear strain in the composite by the relation

Note the shear strain in the core is larger than the effective shear strain in the composite and that small deformations ( ) are assumed in deriving the above relation. The effective shear strain in the beam is related to the shear displacement by the relation

) are assumed in deriving the above relation. The effective shear strain in the beam is related to the shear displacement by the relation

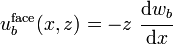

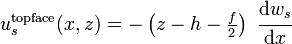

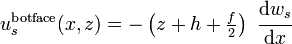

The facesheets are assumed to deform in accordance with the assumptions of Euler-Bernoulli beam theory. The total deflection of the facesheets is assumed to be the superposition of the deflections due to bending and that due to core shear. The  -direction displacements of the facesheets due to bending are given by

-direction displacements of the facesheets due to bending are given by

The displacement of the top facesheet due to shear in the core is

and that of the bottom facesheet is

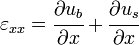

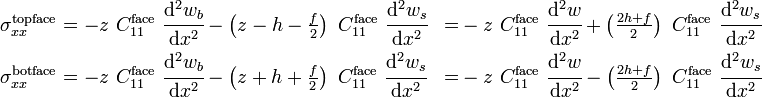

The normal strains in the two facesheets are given by

Therefore

Stress-displacement relations

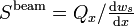

The shear stress in the core is given by

or,

The normal stresses in the facesheets are given by

Hence,

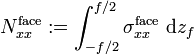

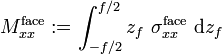

Resultant forces and moments

The resultant normal force in a facesheet is defined as

and the resultant moments are defined as

where

Using the expressions for the normal stress in the two facesheets gives

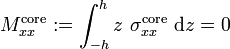

In the core, the resultant moment is

The total bending moment in the beam is

or,

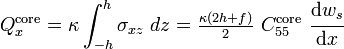

The shear force  in the core is defined as

in the core is defined as

where  is a shear correction coefficient. The shear force in the facesheets can be computed from the bending moments using the relation

is a shear correction coefficient. The shear force in the facesheets can be computed from the bending moments using the relation

or,

For thin facesheets, the shear force in the facesheets is usually ignored.[2]

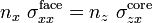

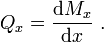

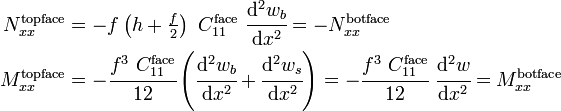

Bending and shear stiffness

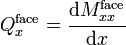

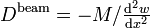

The bending stiffness of the sandwich beam is given by

From the expression for the total bending moment in the beam, we have

For small shear deformations, the above expression can be written as

Therefore, the bending stiffness of the sandwich beam (with  ) is given by

) is given by

and that of the facesheets is

The shear stiffness of the beam is given by

Therefore the shear stiffness of the beam, which is equal to the shear stiffness of the core, is

Relation between bending and shear deflections

A relation can be obtained between the bending and shear deflections by using the continuity of tractions between the core and the facesheets. If we equate the tractions directly we get

At both the facesheet-core interfaces  but at the top of the core

but at the top of the core  and at the bottom of the core

and at the bottom of the core  . Therefore, traction continuity at

. Therefore, traction continuity at  leads to

leads to

The above relation is rarely used because of the presence of second derivatives of the shear deflection. Instead it is assumed that

which implies that

Governing equations

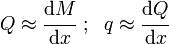

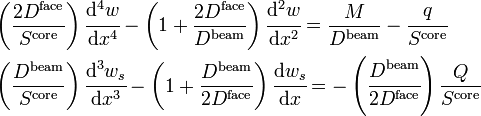

Using the above definitions, the governing balance equations for the bending moment and shear force are

We can alternatively express the above as two equations that can be solved for  and

and  as

as

Using the approximations

where  is the intensity of the applied load on the beam, we have

is the intensity of the applied load on the beam, we have

Several techniques may be used to solve this system of two coupled ordinary differential equations given the applied load and the applied bending moment and displacement boundary conditions.

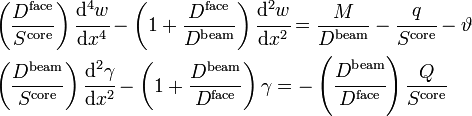

Temperature dependent alternative form of governing equations

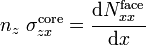

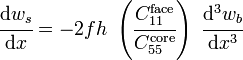

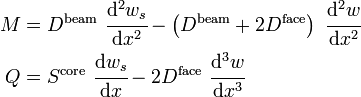

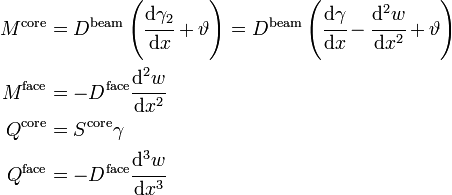

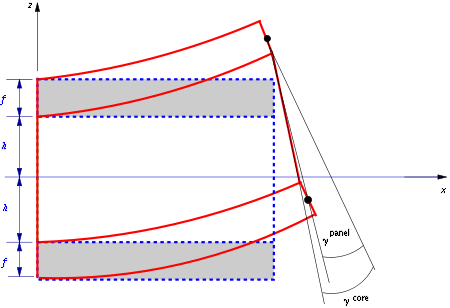

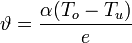

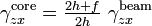

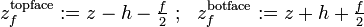

Assuming that each partial cross section fulfills Bernoulli's hypothesis, the balance of forces and moments on the deformed sandwich beam element can be used to deduce the bending equation for the sandwich beam.

The stress resultants and the corresponding deformations of the beam and of the cross section can be seen in Figure 1. The following relationships can be derived using the theory of linear elasticity:[3][4]

where

| transverse displacement of the beam | |

| Average shear strain in the sandwich |  |

| Rotation of the facesheets |  |

| Shear strain in the core | |

| Bending moment in the core | |

| Bending stiffness of the sandwich beam | |

| Bending moment in the facesheets | |

| Bending stiffness of the facesheets | |

| Shear force in the core | |

| Shear force in the facesheets | |

| Shear stiffness of the core | |

| Additional bending as a consequence of a temperature drop |  |

| Temperature coefficient of expansion of the converings | |

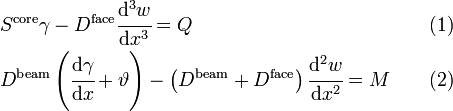

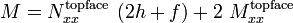

Superposition of the equations for the facesheets and the core leads to the following equations for the total shear force  and the total bending moment

and the total bending moment  :

:

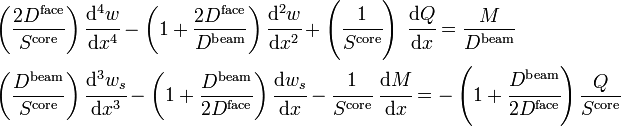

We can alternatively express the above as two equations that can be solved for  and

and  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

Solution approaches

The bending behavior and stresses in a continuous sandwich beam can be computed by solving the two governing differential equations.

Analytical approach

For simple geometries such as double span beams under uniformly distributed loads, the governing equations can be solved by using appropriate boundary conditions and using the superposition principle. Such results are listed in the standard DIN EN 14509:2006[5](Table E10.1). Energy methods may also be used to compute solutions directly.

Numerical approach

The differential equation of sandwich continuous beams can be solved by the use of numerical methods such as finite differences and finite elements. For finite differences Berner[6] recommends a two-stage approach. After solving the differential equation for the normal forces in the cover sheets for a single span beam under a given load, the energy method can be used to expand the approach for the calculation of multi-span beams. Sandwich continuous beam with flexible cover sheets can also be laid on top of each other when using this technique. However, the cross-section of the beam has to be constant across the spans.

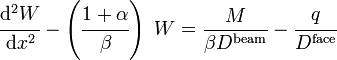

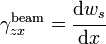

A more specialized approach recommended by Schwarze[4] involves solving for the homogeneous part of the governing equation exactly and for the particular part approximately. Recall that the governing equation for a sandwich beam is

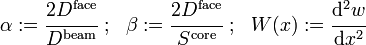

If we define

we get

Schwarze uses the general solution for the homogeneous part of the above equation and a polynomial approximation for the particular solution for sections of a sandwich beam. Interfaces between sections are tied together by matching boundary conditions. This approach has been used in the open source code swe2.

Practical Importance

Results predicted by linear sandwich theory correlate well with the experimentally determined results. The theory is used as a basis for the structural report which is needed for the construction of large industrial and commercial buildings which are clad with sandwich panels . Its use is explicitly demanded for approvals and in the relevant engineering standards.[5]

See also

- Bending

- Beam theory

- Composite material

- Hill yield criteria

- Sandwich structured composite

- Sandwich plate system

- Composite honeycomb

- Timoshenko beam theory

- Plate theory

References

- ↑ Plantema, F, J., 1966, Sandwich Construction: The Bending and Buckling of Sandwich Beams, Plates, and Shells, Jon Wiley and Sons, New York.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Zenkert, D., 1995, An Introduction to Sandwich Construction, Engineering Materials Advisory Services Ltd, UK.

- ↑ K. Stamm, H. Witte: Sandwichkonstruktionen - Berechnung, Fertigung, Ausführung. Springer-Verlag, Wien - New York 1974.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Knut Schwarze: „Numerische Methoden zur Berechnung von Sandwichelementen“. In Stahlbau. 12/1984, ISSN 0038-9145.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 EN 14509 (D):Self-supporting double skin metal faced insulating panels. November 2006.

- ↑ Klaus Berner: Erarbeitung vollständiger Bemessungsgrundlagen im Rahmen bautechnischer Zulassungen für Sandwichbauteile.Fraunhofer IRB Verlag, Stuttgart 2000 (Teil 1).

Bibliography

- Klaus Berner, Oliver Raabe: Bemessung von Sandwichbauteilen. IFBS-Schrift 5.08, IFBS e.V., Düsseldorf 2006.

- Ralf Möller, Hans Pöter, Knut Schwarze: Planen und Bauen mit Trapezprofilen und Sandwichelementen. Band 1, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-433-01595-3.

External links

- Institute for Sandwich Technology

- http://www.diabgroup.com/europe/literature/e_pdf_files/man_pdf/sandwich_hb.pdf DIAB Sandwich Handbook

- http://www.swe1.com Programm zur Ermittlung der Schnittgrössen und Spannungen von Sandwich-Wandplatten mit biegeweichen Deckschichten (Open Source)

- http://www.swe2.com Computation of sandwich beams with corrugated faces (Open Source)

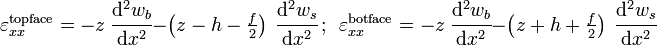

![\begin{align}

\sigma_{xx}^{\mathrm{f}} & = \cfrac{z E^{\mathrm{f}} M_x}{D} ~;~~ &

\sigma_{xx}^{\mathrm{c}} & = \cfrac{z E^{\mathrm{c}} M_x}{D} \\

\tau_{xz}^{\mathrm{f}} & = \cfrac{Q_x E^{\mathrm{f}}}{2D}\left[(h+f)^2-z^2\right] ~;~~ &

\tau_{xz}^{\mathrm{c}} & = \cfrac{Q_x}{2D}\left[ E^{\mathrm{c}}\left(h^2-z^2\right) + E^{\mathrm{f}} f(f+2h)\right]

\end{align}](../I/m/6cc32561d649da3d4fc49b684e5d4dbe.png)

![\tau^{\mathrm{face}}_{xz}(x,z) = \cfrac{Q_xE^f}{D}\int_z^{h+f} z~\mathrm{d}z + C(x)

= \cfrac{Q_x E^f}{2D}\left[(h+f)^2-z^2\right] + C(x)](../I/m/ab91b2ae84297f521de8761197c5ced9.png)

![\tau^{\mathrm{core}}_{xz}(x,z)

= \cfrac{Q_x}{2D}\left[ E^c\left(h^2-z^2\right) + E^f f(f+2h)\right]](../I/m/4ab78d9f7cc0966d1057f942904ad562.png)

![\begin{align}

\sigma_{xx}^{\mathrm{f}} & \approx \cfrac{z M_x}{\frac{2}{3}f^3 +2fh(f+h)} ~;~~ &

\sigma_{xx}^{\mathrm{c}} & \approx 0 \\

\tau_{xz}^{\mathrm{f}} & \approx \cfrac{Q_x}{\frac{4}{3}f^3+4fh(f+h)}\left[(h+f)^2-z^2\right] ~;~~ &

\tau_{xz}^{\mathrm{c}} & \approx \cfrac{Q_x(f+2h)}{\frac{2}{3}f^2+h(f+h)}

\end{align}](../I/m/ddbbad0af1909310fbb445f83c28cd76.png)

![\begin{align}

\sigma_{xx}^{\mathrm{f}} & \approx \cfrac{zM_x}{2fh(f+h)} ~;~~&

\sigma_{xx}^{\mathrm{c}} & \approx 0 \\

\tau_{xz}^{\mathrm{f}} & \approx \cfrac{Q_x}{4fh(f+h)}\left[(h+f)^2-z^2\right] ~;~~&

\tau_{xz}^{\mathrm{c}} & \approx \cfrac{Q_x(f+2h)}{4h(f+h)} \approx \cfrac{Q_x}{2h}

\end{align}](../I/m/73d153225dc707c3c8ec0642afd5128c.png)

![M \approx -\cfrac{f[3(2h+f)^2+f^2]}{6}~C_{11}^{\mathrm{face}}~\cfrac{\mathrm{d}^2 w}{\mathrm{d} x^2}](../I/m/c9bc7943043d51c24be886d08f2c42c9.png)

![D^{\mathrm{beam}} \approx \cfrac{f[3(2h+f)^2+f^2]}{6}~C_{11}^{\mathrm{face}} \approx \cfrac{f(2h+f)^2}{2}~C_{11}^{\mathrm{face}}](../I/m/ce9a0c8bc73eb0ab2b7aad98f6ae79b2.png)