San Miguel Zinacantepec

| Zinacantepec | ||

|---|---|---|

| Town & Municipality | ||

|

Main Plaza of Zinacantepec | ||

| ||

Zinacantepec Location in Mexico | ||

| Coordinates: 19°17′00″N 99°44′00″W / 19.28333°N 99.73333°WCoordinates: 19°17′00″N 99°44′00″W / 19.28333°N 99.73333°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| State | State of Mexico | |

| Founded | 18th century | |

| Municipal Status | 1826 | |

| Government | ||

| • Municipal President | Olga Hernández Martínez | |

| Area | ||

| • Municipality | 308.68 km2 (119.18 sq mi) | |

| Elevation (of seat) | 2,740 m (8,990 ft) | |

| Population (2005) Municipality | ||

| • Municipality | 136,167 | |

| • Seat | 46,569 | |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | |

| Postal code (of seat) | 51350 | |

| Area code(s) | 722 | |

| Website | (Spanish) /Official site | |

Zinacantepec is a town and municipality located just west of the city of Toluca in Mexico State, Mexico.[1] The community is named after a small mountain which contained two caves which used to be filled with thousands of bats.[2] Zinacantepec is Nahuatl for Bat Mountain. Its Aztec glyph is a bat on a mountain.[1] In the 18th century, the population of this mountain moved to settle alongside the Franciscan monastery established here in the 16th century.[2] This monastery is the best preserved of a network of missionaries established in the Toluca Valley in the mid 16th century. Today, the complex functions as the parish church, with the cloister dedicated as the colonial era museum of the state of Mexico.[3]

History

The history of the town and municipality begins about 1500 years ago at an elevation now named “Cerro de Murciélago” or Bat Mountain. The hill contained two caves that used to be filled with thousands of bats. The presence of these animals was considered a sign of fertility. The hill remained populated until the 18th century, when a plague pushed the population toward the Franciscan monastery, which functioned as a hospital.[2] A deity named Zinacan was associated with the mountain. Shortly after the Spanish Conquest, this deity would be believed to be an incarnation of the Devil.[4] Today, the bat population of the area is limited to a few caves in the Nevado de Toluca National Park.[2] The mountain is mined for gravel and alongside it is the Hacienda de Santa Cruz de los Patos, which is now part of the Mexiquense College, as a research center and library.[4]

The earliest known ethnicity in the area is the Otomi, who still are present, especially in smaller communities in the municipality such as San Luis Mextepec and Acahulaco. In the south of the municipality, there are Matlatzincas; however, there are very few. The area was conquered by the Aztecs in the latter 15th century by Axayacatl. Zinacantepec was then ruled from Tlacopan as a tributary province.[1]

During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Otomis sided with the Spanish and the Matlazincas against. Gonzalo de Sandoval came to the Toluca Valley with 18 cavalry and 100 infantry. They were joined by 60,000 Otomi and conquered the Matlatzincas. The area around what is now the city of Toluca, including Zinacantepec, came under the rule of Hernán Cortés administrated by his cousin Juan Gutiérrez Altamirano in what would become the County of Santiago de Calimaya. The west part of the valleybecame part of the encomendero of Juan de Sámano. This same family founded the Hacienda de laGavia which owned much of the arable land in the municipality.[1]

While no battles were fought here during the Mexican War of Independence, many here joined the army of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla against the colonial government, with many fighting at the Battle of Monte de las Cruces. After the war, Zinacantepec became a municipality in 1826.[1]

During the Reform War, vandalism and general lawlessness gripped the municipality as well as neighboring Toluca. This was finally put to an end by Felipe Berriozabal in the 1860s. During the Mexican Revolution, Zinacantepec was taken in 1912 by General José Limón and Alberto Sámano in support of Francisco I. Madero. The Zapatistas camped in some of the smaller communities of the municipalities, confronting federal forces and sacking homes.[1]

The 2000s to the present are marked by political and economic problems for the municipality. Starting in 2005, the municipality has had serious financial difficulties, mostly due it its debt. These financial problems have caused inadequacies in the drainage, garbage collection and health services.[5] In 2007, residents protested the lack of adequate garbage collection by bringing their garbage to the municipal palace and threatened to leave it there. They claim that in some areas, garbage had not been collected for months, requiring children to wear masks on their way to school.[6] In 2008, councilman Leonardo Bravo Hernandez was sentenced to 18 months for the misappropriation of 100 million pesos during the city council session of 2003–2006.[7] José Consuelo González Xingú, a municipal delegate was shot and killed in January 2010 in San Antonio Acajhualco, a community in the municipality. Gonzalez Xingú had presented a complaint to the Mexico State Commission of Human Rights for acts of intimidation and abuse among the municipal police force. Prior to this, Gonzalez Xingu had also made a formal complaint to the state about the municipal president for nepotism, which was ratified. The municipal president denies involvement.[8] The municipal president, Gustavo Vargas Cruz, has been under investigation for the murder of Jesus Consuelo Xingú. One of the reported gunmen has been apprehended.[9]

Until 2008, Zinacantepec was the only municipality with roads with no right-of-way markers. In that year, the direction and signaling of all the roads was reworked in a systematic way.[10]

Town

Although just west of the city of Toluca, Zinacantepec remains mostly rural, preserving much of its traditions and customs from over 300 years ago.[11] Major religious festivals include one in honor of the Virgin of Los Dolores (also called Del Rayo) from May 21 to 23 and one for the patron of the town, the Archangel Michael on December 3.[1] One legend associated with the Virgin was that the image was left at the local monastery by a woman who had been cured of the plague. In 1762, a bolt of lightning struck and destroyed the church tower, but the Virgin, who was inside, was unharmed.[4]

The town’s main church, the Parish of San Miguel, was the monastery church until the monastery church was closed during the Reform War. The church remained open but with non-monastic priests.[1] The structure dates from the 17th century, and has typical features for constructions from that time such as a cruciform plan, a central dome and an ornate two tier bell tower. Since it was Franciscan, the facade is a sober Baroque with minimal ornamentation. Inside, on the south wall is a stone pulpit decorated with carved scales. It also contains an unusual ceramic baptismal font which dates from the early colonial period. The rest of the church is fairly modern but colonial paintings and church furnishings from earlier periods can be found in the sacristy.[3]

Market day is Sunday when the street fill with vendors and local specialties such as red and green mole, local produce, tamales and small tacos made with corn tortillas about 6 cm in diameter. Local drinks include pulque and fruit liquors.[1][4]

Universidad Politécnica Del Valle de Toluca has its secondary campus in the town. It offers programs of study in engineering and business.[12]

Monastery complex

The Toluca Valley was evangelized by the Franciscans starting from the 1520s. During the 1550s and 1560s, a network of missions was built spreading out from Toluca, where missionaries would begin by studying the languages and customs of the native peoples of the valley. Of these missions, the monastery at Zinacantepec is the best preserved.[3] The mission with its open chapel was begun in 1550, with the rest of the monastery built between 1560 and 1570.[1][3] The modern town of Zinacantepec was built around it when the local populace abandoned the nearby hill and settled around the monastery in the 18th century.[2] The monastery remained in operation from the early colonial period until the Reform War when it was closed by the government. It is said that it was occupied by Zapatista forces during the Mexican Revolution. Later in the 20th century, part of it was used to house priests who ran the still functioning Parish of San Miguel. It was declared a national monument in 1933.[1] In 1976, the State of Mexico took over the cloister portion of the complex (leaving the church open for worship) and began to renovate it with the purpose of founding a museum, along with the Fondo Nacional para Actividades Sociales (FONAPAS).[1] The museum was opened in 1980 as the Museo del Virrenato del Valle de Toluca (Museum of Viceregal Art of the Valley of Toluca.[13] The collection is housed in the rooms of the cloister with the open chapel area serving as the main entrance.[1] The oldest portion of the complex is the open chapel, which dates from the time when the structure began as a small mission. The chapel is integrated into a “porteria” (a porch like entrance or arcade) in the front of the building, which was added in the 1560s. The altarpiece of the chapel is recessed into the back wall which has a pediment and contains ten panels. The central figure is of the Archangel Michael, the original patron saint of the mission. Above him is a female saint, possibly Saint Claire with archangels and luminaries of the Church on the surrounding panels. God, the Father looks down from the pediment with the Four Evangelists at the base.[3]

In a small room on the south end of the porteria is the original mission baptistery. Here is the first baptismal font, which is a huge monolithic basin cut from gray volcanic stone. The outside is carved with both Christian and indigenous symbols. Carved medallions illustrate episodes in Christ’s life, and there is a relief of the Archangel Michael casting Lucifer from heaven. The indigenous symbolism includes Aztec speech markers and pre-Hispanic water imagery.[3] Encircling the cord rim is a Spanish and Nahuatl inscription which says, “This baptismal font and the room in which it is found was mandated by the venerable guardian Fray Martin de Aguirre in the village of Zinacantepec in the year 1581.”[4] This font is one of the most important pieces at the museum.[14]

Above the low main door into the cloister, there is a mural from the 16th century called the “Tree of Life” which illustrates a genealogical tree of the Franciscan Order, growing from the chest of Francis of Assisi. Unlike many of the other frescos, this one contains various colors, including red and green accents, flesh tones and framed by bands of color.[3] This murals as well as the font and the panels of the altarpieces were designed for the early evangelical efforts of the monastery.[1]

Inside the main entrance is a vestibule which leads to the main courtyard of the cloister. This area is plainer than the porteria, with only black and white 16th-century frescos adorning the walls and some gray gargoyles on the upper parts of the columns. Many of the frescos and gargoyles are now fragmentary. The cloister has two floors and courtyard surrounded by 20 arches supported by Tuscan columns. The ceilings are made from large wood beams and the floors are paved in local stone.[3][4] On the north and south sides of the upper cloister there are two sundials. One is meant to be used in the summer and the other in winter.[1]

The cloister complex is now the Museo Virreinal de Zinacantepec (Viceregal Museum of Zinacantepec).[14] It has twenty exhibition halls, with more than 275 works of art over the three centuries of the colonial period in Mexico. The collection also include more ordinary items such as cooking utensils, weapons, furniture and clay objects.[13] The collection includes sixty paintings of viceroys and archbishops of New Spain, wood sculptures of religious figures, Spanish armour and a Christ figure made of “pasta de cana” or meshed corn stalks.[1] Most of the paintings have been classified an anonymous due to the lack of signatures. The museum is considered to have one of the most important colonial era collections in the state, along with the Ex Monastery of Acolman and the Museo Nacional del Virreinato in Tepotzotlan. More than 300 pieces of the collection were the subject of a major restoration project in 2003 at a cost of 500,000 pesos.[14]

Another important aspect of the museum is its library. This library contains 1,587 volumes about 43 subjects including theology, philosophy, law, history and others. The oldest book here is a copy of the Suma Teologia by Thomas of Aquinas. The books had been in the care of the Museum of Bellas Artes in Mexico City than the Municipal Library of Toluca before coming to Zinacantepec, The books have been available to academics since 2005. The bookshelves and some other furniture are original to the monastery.[15]

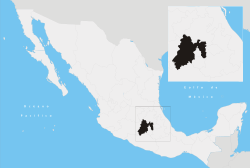

Municipality

As municipal seat, the town of Zinacantepec is the local governing authority for more than 130 other named communities,[16] which together form a territory of 308.68km2.[1] About one third of the municipality’s population lives in the town proper.[16] Despite its rural and traditional nature, very few speakers of indigenous languages are left. The municipality is bordered by the municipalities of Almoloya de Juárez, Texcaltitlán, Toluca, Calimaya, Temascaltepec, Amanalco, Villa Guerrero and Coatepec Harinas.[1]

The dominating geographical feature here is the Nevado de Toluca volcano, with a significant part of the National Park being located in the municipality. Elevation here varies between 3,200 and 2750 meters above sea level and the soil is made of composites from past lava flows and ash deposits from the nearby volcano, which is now dormant. Some other smaller volcanoes exist here, such as the Molcajete, which were formed by the Nevado’s third stage of eruptions. Surface water is mostly in the form of the Tejalpa River, some small streams and some fresh water springs, all of which are fed by the runoff from the Nevado de Toluca. The area has a temperate, mildly wet climate with freezes common in the foothills of the volcano. Highs in the summer are around 28C with lows in the winter can get to −5C. Most rains falls between the months of June to October. Much of the wild vegetation is forest with pines, cedars and fir trees, which mostly exist in the national park, along with most of the wildlife, which includes squirrels, opossums, coyotes, eagles, crows and some snakes and other reptiles.[1]

Agriculture is still the main economic staple of the municipality, employing the vast majority of residents. Crops grown here include corn, potatoes, fava beans, carrots, spinach, onions, radishes and other vegetables, mostly grown on family farms. The raising of livestock is important here with cattle, pigs and sheep being the principle animals.[1] A few haciendas still exist including the San Juan de la Huertas and the San Pedro Tajalpa, where Porfirio Díaz and his wife spent time in its large mansion, which still exists.[4] There is one small industrial zone which contains a number of industries with the largest being BIMBO, Coca Cola and Gas CIMSA. Commerce is mostly limited to basic needs. There are sand and gravel mines such as San Juan de las Huertas and Loma Alta in the community of San Cristobañ Tecolit.[1]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zinacantepec. |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 "Enciclopedia de los Municipios de Mexico Estado de Mexico Zinacantepec" (in Spanish). INAFED. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cruz, Raúl (November 1, 2008). "Dan identidad a Zinacantepec" [They give identity to Zinacantepec]. Reforma (in Spanish) (Mexico City). p. 6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 "Zinacantépec, a colonial convento near Toluca, Mexico". Exploring Colonial Mexico The Espadaña Press Web site. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Valdespino, Martha (June 17, 1999). "Vamonos de Paseo/ Zinacantepec: Historias bajo el Nevado" [Lets look around/Zinacantepec:Stories under the Nevado]. Reforma (in Spanish) (Mexico City). p. 6.

- ↑ Gomez, Enrique I (January 25, 2005). "Preven diputados reducir adeudo a Zinacantepec" [Deputies foresee reduction in Zinacantepec’s debt]. Reforma (in Spanish) (Mexico City). p. 9.

- ↑ Miranda Torres, Rodrigo (November 28, 2007). "La alcaldía de Zinacantepec, un "basurero"" [The municipality of Zinacantepec, a “dump”]. El Sol de Toluca (in Spanish) (Toluca, Mexico). Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ Dávila, Israel (October 26, 2008). "Saldría con fianza ex edil de Zinacantepec" [Ex alderman of Zinacantepec skips bail]. La Jornada (in Spanish) (Mexico City). Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ Dávila, Israel (January 14, 2010). "Asesinan a delegado municipal que denunció anomalías en Zinacantepec" [Municipal delegate who denouced anomalies in Zinacantepec murdered]. La Jornada (in Spanish) (Mexico City). p. 30. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Alcalde de Zinacantepec sigue bajo investigación por homicidio" [Mayor of Zinacantepec still under investigation for murder]. Milenio (in Spanish) (Mexico City). February 1, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ Miranda Torres, Rodrigo (July 3, 2008). "Zinacantepec, único municipio sin reordenamiento vial" [Zinacantepec, the only municipality without road realignment]. El Sol de Toluca (in Spanish) (Toluca, Mexico). Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ Martinez, Israel (November 9, 2002). "Zinacantepec: Evocan pasado religioso" [Zinacantepec:Evoking religious past]. Reforma (in Spanish) (Mexico City). p. 10.

- ↑ "Universidad Politécnica del Valle de Toluca" (in Spanish). Acolman, Mexico: Universidad Politécnica del Valle de Toluca. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Sobre el exConvento" (in Spanish). Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Velasco, Eduardo (January 3, 2002). "Rescatan arte sacro de Zinacantepec bajo el Nevado" [Rescuing sacred art of Zinacantepec]. Reforma (in Spanish) (Mexico City). p. 3.

- ↑ "Museo de Zinacantepec, depósito de joyas de la historia nacional" [Museum of Zinacantepec, deposit of jewels of national history]. Noticias Televisa (in Spanish) (Mexico City). NOTIMEX. December 29, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "INEGI Census 2005" (in Spanish). Retrieved March 3, 2010.