Salvador Minguijón Adrián

| Salvador Minguijón Adrián | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Juan Salvador Minguijón Adrián 1874 Calatayud |

| Died |

1959 Zaragoza |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Ethnicity | Spanish |

| Occupation | academic |

| Known for | academic, theorist |

Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista, Partido Social Popular, Unión Patriótica, |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Juan Salvador Minguijón Adrián (Calatayud, 1874 - Zaragoza, 1959) was a Spanish historian of law and a Carlist and Christian theorist.

Family and youth

.jpg)

Salvador Minguijón Adrián originated from an Aragonese family of petty officials and artisans. His paternal ancestors came from the village of Terrer in South-Western Aragon, where Salvador's grandfather worked as a primary school teacher; his father, Jorge Minguijón, was a local administrative clerk. The family of his mother, María Antonia Adrián, lived in the town of Calatayud, where the maternal grandfather worked as a carpenter.

Raised in a profoundly religious family, following his childhood spent in Terrer the young Salvador entered the diocesan seminary in Zaragoza, intending to be either a priest or a secondary school teacher. He abandoned the ecclesiastical career path and commenced university studies at the Universidad de Zaragoza, graduating in Filosofía y Letras in 1896. He moved to Madrid later on to pursue his education in law at the Universidad Central (later to become Universidad Complutense), where he obtained his diploma Cum Laude in 1900 and continued with doctoral research. In 1903 Minguijón commenced the career of a lawyer becoming a notary in Sabiñán, serving in the same role also in the neighbouring village of Brea since 1905. He obtained the PhD laurels - again Cum Laude - in 1906, his thesis titled La responsabilidad civil extracontractual.

Academic

Following a number of applications to various Aragonese colleges and universities, in 1905 Minguijón became professor auxiliar interino gratuito at the Facultad de Derecho of the Zaragoza University, the following academic year promoted to professor auxiliar interino retribuido and to professor auxiliar numerario de segundo grupo by 1907. The same year he filled the vacancy in Historia General del Derecho Español as assistant-professor; he assumed the Universidad de Zaragoza chair of Historia General del Derecho in 1911, the position he would retain throughout the following 33 years.

Starting 1911 Minguijón began to publish university booklets in history of law; the series summarised previous studies, but was also increasingly based on own research, especially focused on medieval and foral Spanish legislation. It turned out to be a basis for his monumental synthesis Historia del Derecho español, published in 1927, re-issued in few editions until the mid-1950s and serving as a textbook for generations of Spanish students of law. The work, along articles in scientific periodicals, translations (esp. of the German historian of theology Martin Grabmann) and books in history of ideas has firmly established Minguijón's position among the Spanish catedraticos of law; he was a member of numerous juridical scientific and corporative institutions of the country. Apart from history of law, his interest gradually focused on sociology and anthropology.

_01.jpg)

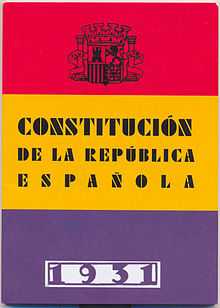

Minguijón's juridical career was crowned in 1933, when he was elected as an academic nominee as one 35 members of Tribunal de Garantías Constitucionales, the Spanish constitutional court. The elections marked the first defeat of the Left in the Republican political life and reflected both Minguijón's growing prestige and his conservative leaning. Continuing with academic duties in Zaragoza he settled in Madrid and served as a top magistrate until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Appointed to the Francoist Tribunal Supremo in 1938, in 1941 he became member of Real Academia de Ciencias Morales y Políticas; in the early 1940s he also briefly chaired cátedra de sociología at the Madrid Universidad Central. Resigned from all public duties in 1944.

Carlism and minguijónismo

Having inherited conservative and religious outlook, in the beginning of his scholarly career Minguijón got his Carlist leaning reinforced at the University; in the early 20th century the Zaragoza Law Faculty was dominated by Jaimistas from the Comín dynasty of Traditionalist leaders. However, at that time Carlism was increasingly marginalised as a political force and suffered also apparent decay of its ideological base. Formatted during the 19th century struggles against the liberals, it was yet to acknowledge new political and social phenomena: growing social conflict, Spanish and peripheral nationalisms and emergence of mass-based socialist and anarchist movements. Apart from Juan Vázquez de Mella, Salvador Minguijón was one of the two theorists who attempted to address the challenge of the new times. His concept, initially expressed as minor public and press contributions, was summarised in La crisis del tradicionalismo en España, published in 1914.

Minguijón remained convinced that the Traditionalist dogma was perfectly valid, though it had to be renewed and its application re-defined; he viewed it not as a fixed set of ideas, but as an adaptive approach to problems of human civilisation. The practical conclusion was that against the rise of new threats the Carlists should abandon their intransigence and seek alliance with all the political forces sharing the same lowest common denominator. He advocated in particular rapprochement with the Integristas, who led by Ramón Nocedal separated from mainstream Carlism 20 years earlier, with Catalans from the conservative and Catholic Lliga Regionalista of Francesc Cambó, and with the Mauristas, a right-wing faction of the Conservative Party grouped around Antonio Maura. The alliance as envisaged by Minguijón implied that the Carlists should soften their approach to Catalanism, up to recognition of separate Catalan legislation and administration, and park their dynastical claims, assuming that the monarchy would evolve towards a Traditionalist model anyway.

Within the movement Minguijón's proposal was appreciated as an elaborated and genuine attempt to revitalise Carlism, though the critics pointed out that minguijónismo would be another version of pidalismo, leading to opportunist amalgamation of Traditionalism within a broad conservative spectrum and its ultimate loss of its own identity. Rebuked in the Carlist press titles like El Correo Catalán, in 1915 the vision (though not the author himself) was eventually disavowed by the claimant Don Jaime, who confirmed intransigence on dynastical issues and permitted at best neutral approach towards moderate Catalanism of La Lliga. During the following years the internal debates within Carlism got dominated by the dissenting views of Vázquez de Mella. When the Mellistas broke away in 1919 Minguijón maintained loyalty to Don Jaime, and remained influential enough to enforce (together with Francisco Martín de Melgar) resignation of Pascual Comín y Moya from the national Carlist leadership.

Dictatorship and republic

Unlike many old-fashioned Carlist leaders Minguijón remained perfectly aware of the social transformation of Spain in the commencing industrial era; he grew increasingly concerned with problems of capital and labor relations, wealth distribution, class struggle and poverty. Contributing to local Catholic periodicals like El Noticiero, in 1907 together with Severino Aznar Embid and Inocencio Jiménez Vicente he founded the La paz social periodical. He kept publishing also during the following decades, most prominently in El Debate, his contributions advocating re-organisation of social order along the lines sketched by the encyclicals of Leo XIII. The problem was also addressed in two of his studies, Hombres e ideas. Estudios sociales (1910) and Propiedad y trabajo (1920). Together with other Aragon activists he formed grupo coordinador de Zaragoza of the Asociación Católica de Propagandistas. In the early 1920s he tried to pave his own political way when co-founded Partido Social Popular, one of the first European political incarnations of Christian Democracy, soon dissolved by the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera. Unperturbed, in the late 1920s Minguijón co-operated with Unión Patriótica, a feeble dictator's attempt to institutionalise the system and build an own "state party".

The subsequent pamphlets and booklets, Humanismo y nacionalidad (1929), Al servicio de la Tradición (1930), La función social de la propiedad (1930); La crisis de la libertad (1934), La Democracia (1934) and La Propiedad (1935) demonstrated that while Minguijón still nurtured a Traditionalist ideological core, his political outlook evolved towards Christian social teachings. The typical Carlist intransigence, which attracted many activists and politicians horrified by militant secularism and socialism of the Republic (like Maria Rosa Urraca Pastor or José María Valiente Soriano), in case of Minguijón proved to be a discouraging factor. He drew closer to Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA), a mid-1930s preconfiguration of Christian Democratic if somewhat authoritarian political party, and contributed both theoretically and organisationwise, highly skeptical if not entirely averse towards the republican parliamentarian model. He bestowed the concept of "organic democracy", meant as a representative system channelled through established formal institutional bodies, not as an individualist one-man-one-vote pattern.

Minguijón found himself in an awkward position when sitting in Tribunal de Garantías Constitucionales; the body was entrusted with safeguarding the juridical republican system, while he was growing at the same time increasingly disillusioned with the legal order of the Republic. His struggle to maintain impartiality was reflected in a highly contested vote on the Catalonian Leases Act, known as Ley de Contratos de Cultivo; he did not join his fellow Carlist Víctor Pradera Larumbe voting against the Catalan liberties and tenants' claims, but recorded a votum separatum. Minguijón's dilemma was terminated by the outbreak of the Civil War, which surprised him in Burgos. He formally resigned from the anyway defunct Tribunal in September 1936, though agreed to form part of the Francoist legal system by entering the Nationalist Tribunal Supremo between 1938 and 1944.

Legacy

_02.jpg)

Juan Salvador Minguijón Adrián has earned no monography so far. As an academic and a scholar in history of law he is acknowledged by Universidad de Zaragoza and Real Academia De Ciencias Morales Y Políticas (RACMYP), mostly due to his long service in Zaragoza and his Historia del derecho español. He is also featuring as a distinguished citizen on various Aragon websites.

As a political theorist and student of anthropology/social sciences Minguijón was considered an authority and master by Rafael Gambra Ciudad, who shared his approach and elaborated his conclusions further on. Politically Minguijón is defined as socialcatólico or a supporter of corporativismo católico, in-between Catholic authoritarianism and Right-wing Christian democracy, his anti-liberal stance often tuned down and his social concern put into the forefront. However, he is sometimes referred to against the background of bonapartismo or even marginally mentioned in studies on ideological origins of Francoism; occasionally he is contemptuously dubbed a "completely forgotten figure". There is a major street commemorating Minguijón in the Las Fuentes district of Zaragoza.

See also

- Carlism

- Christian democracy

- Legal history

References

- Severino Aznar y Embid, Salvador Minguijón Adrián, [in:] Revista Internacional de Sociología 17 (1959)

- Juan Francisco Baltar Rodríguez, Minguijón y Adrián, Juan Salvador (1874-1959), [in:] Diccionario de Catedraticos of Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

- Juan Francisco Baltar Rodríguez, Los Ejercicios de oposiciones a professor auxiliar de Salvador Minguijón, [in:] Glossae. European Journal of Legal History 10 (2013)

- Jacek Bartyzel, Bandera Carlista, [in:] Umerac ale powoli, Kraków 2006, ISBN 8386225742

- Jesús Lalinde Abadía, Minguijón Adrián, Juan Salvador, [in:] En Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa (vol. VIII), Zaragoza 1982

- Sergio Fernández Riquelme, Sociología, corporativismo y política social en España. Las décadas del pensamiento corporativo en España: de Ramiro de Maeztu a Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora (1877-1977), [PhD thesis], Murcia 2008

- José Orlandis Rovira, Juan Salvador Minguijón Adrián, [in:] Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español, XXIX, Madrid 1959

External links

- Minguijón at Universidad Carlos III

- Minguijón setting up Partido Social Popular

- Minguijón, constitutional court and the Catalan Leases Act

- Minguijón at Centro Gonzalo Diaz y Dolores Abad

- Minguijón according to Hombres y documentos de la filosofía española

- Minguijón and Catholic corporativism

- Minguijón, bonapartism and origins of Francoism

- Minguijón and academic appointment process in early 20th century Spain

- Minguijón and Aznar (including a photo from 1906)

- Minguijón as a "completely forgotten" figure

- Minguijón's press obituary