Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin

Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin is a large oil and tempera on oak panel painting attributed to the Early Netherlandish artist Rogier van der Weyden, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It shows Luke the Evangelist, patron saint of artists, sketching an apparition of the Virgin Mary cradling the Child Jesus. Van der Weyden probably completed the work between 1435 and 1440, perhaps for the Guild of Saint Luke in Brussels. The panel's atmospherics are achieved through dramatic use of chiaroscuro and rich iconography and symbolic motifs. The figures are positioned in a borgeoise interior, which leads out towards an inner courtyard, a river and town and an expansive scape. The courtyard contains an enclosed garden, one of the many indications of Mary's purity. Illustionic carvings of Adam and Eve on the arms of Mary's throne emphasise her son's role in redeeming mankind from original sin.

Three surviving near contemporary copies are held in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the Groeningemuseum, Bruges, and the Hermitage Museum, Leningrad.[1] The Boston panel has been established as the original; it has heavily reworked underdrawings absent in the other examples. It is in relatively poor condition and has suffered considerable surface damage despite extensive restoration and cleaning since work began in 1932.

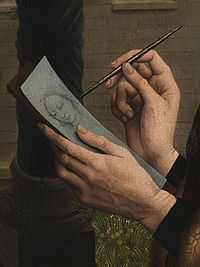

Rogier was heavily influenced by Jan van Eyck, and the image is in many aspects a free copy of Madonna of Chancellor Rolin.[2] It closely follows the overall composition, especially the arches, elements of the landscape and the colours of the figures clothes. However the latter are inverted and van der Weyden makes significant other deviations. Luke is depicted as the foremost actor, and his profession as a painter is heavily and more realistically emphasised as a 15th-century trade, as is his mastery. Luke uses silverpoint, a very difficult medium to control 'on the fly' as he is shown here. Further, van der Weyden has associated himself giving Luke a likeness that is almost certainly a self-portrait.[3] Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin was probably donated to the City Painter of Brussels, following his apprenticeship with Robert Campin.[4] As the work depicts the patron of artists interacting with a member of the holy family, it may reflect the 15th-century change in the status of painters from craftsmen to artistic creatives.[5]

Commission

According to legend, Luke the Evangelist painted the first portrait of the Virgin and Child, and until the early Renaissance painters aspired to exactly follow his idealised model. Thus their depictions were relatively static until the end of the Byzantine era of icons. During the Early Renaissance, images of the Virgin and Child were more commonly found in Northern than Italian art; in the Low countries, Luke was pofen anointed patron of painters' guilds.[6] This historical link to the holy family explains the high instance of faithful reproductions of images of this type.[7] St Luke is credited with painting the Cambrai Madonna, a copy of an earlier Byzantine depiction of Virgin and Child, which became a model for devotional works, with "numerous miracles were attributed to it".[8] It was relocated to France from Rome in 1440, and at least 15 high quality copies were in existence four years later.[7] The work was regarded as an example of St Luke's skill and contemporary painters strove to emulate him in their depictions of Mary. Popular belief held Luke's portrait of Mary captured her essence, and painters strove to imitate the representation.[8]

Van der Weyden's painting may have been commissioned for the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula, Brussels, where he is buried,[9] or the Brussels' painters' guild.[10] It was probably not designed as a single, stand alone panel, but as a triptych altarpiece.[11] Similar to Petrus Christus's A Goldsmith in His Shop, described as part of a "vocational" or "occupational" altarpiece,[12] van der Weyden's St Luke celebrates a specific trade, in this case painting. By depicting a saint as a fellow practitioner, van der Weyden is attempting to confer a "special status on its practitioners".[10]

Description

Material

The panel is formed from four individual pieces of oak. The ground is of chalk, bound with glue.[13] The dominant pigments are lead white, charcoal black, ultramarine, lead tin yellow, verdigris and red lake.[14]

Landscape and setting

The painting is set within an architectural space with a barrel vault ceiling, inlaid tiled flooring, and stained glass windows. The outer wall, or loggia, sits on a bridge over a river or harbour bay.[15] The figures are framed by three arches looking outwards towards a detailed background city and landscape.[16] Art historian Jeffrey Chipps Smith notes how the transition between the grounds establishes a "complex spatial space in which [van der Weyden] achieved an almost seamless movement from the elaborate architecture of them in the main room to the garden and parapet of the middle ground to the urban and rural landscape behind".[17]

Van der Weyden closely follows van Eyck's c. 1435 Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, though there are significant differences. The landscape is less detailed and contains fewer human figures. While van Eyck's landscape is left open, van der Weyden's is enclosed,[18] and is set at a considerably higher distance and altitude.[19] As in the van Eyck, two figures lead to a bridge looking out into the distance. They may not carry specific identities,[20] but have occasionally been identified as Joachim and Anne, the Virgin's parents.[21] The background shows a garden, with plants set in vertical tiers.[18]

The two figures in the mid-ground stand at a battlement wall, with their backs turned against the viewer, as they look outwards. Technical analysis shows that they were heavily reworked both in the underdrawing and the final painting.[19] the In van Eyck's painting the right hand figure wears a red turban, a motif widely thought to be the artist's indicator when placing a self-portrait; similar images can be found on the London Portrait of a Man and subtly in the knight's shield in the Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, now in Bruges. In the Rolin painting he turns to face his companion, pointing outwards. In the van der Weyden, the left hand figure seems similarly protective of his friend, who in this panel is a female. The left hand figure in the van Eyck represent the artist's brother Hubert, who died around 1426. If van Eyck placed a small self-portrait into his Rolin panel, that van der Weyden expounded with a very direct self-portrait of his own in his free copy is little short of remarkable.[22]

The art historian Alfred Acres views the mid-ground figures as preoccupied with "looking". The male figure points outwards to indicate the landscape both to his friend, and the viewer. They are set in the center of the painting.[23]

Figures

Mary sits before a brocade canopy acting as a cloth of honour,[24] on the foot stool of a wooden bench that is attached to the wall behind her.[25] Luke enters from the small room behind him. The room is rich with his symbols; including a sleeping ox and open book representing his Gospel.[17] He is painted with more naturalism than the Virgin; his eyes are more realistically drawn. Christ's conform to the then idealised form, as simple crescents. Mary's are formed from curved lines typical of late Gothic ideals of feminine beauty.[26]

Many features, including Luke's hat and fur trimmed red clothing, are of contemporary fashion; indicators of high born 15th-century aristocracy. In contrast to earlier portrayals, Luke is beardless and relatively youthful; close to the age van der Weyden would have been in the mid-1430s.[27] His features are not idealised; he has light stubble and greying hair.[28] A small ink bottle hangs from his belt.[29] His eyes are attentively fixed on the Virgin.[25]

Mary wears a purplish red-embroidered dress, which has brocade cloth with extensive fur linings. Her hair is loose and she has a light veil around her neck. She is shown in the act of nursing, which, according to Blum, brings her "closer to humanity", and places her in the earthly realm, "caught in the world's time as well as space".[28] Studies of the underdrawing shows the artist intended a van Eyckian angel crowning the Virgin, but omitted it from the final painting.[30] He heavily reworked the positioning of the three main figures even towards the end of completion. Mary's head was tilted to the right, but ends up upright.[31] The draperies of the mantels were at first larger.[32] Christ's body at first faced Luke, but was later tilted in the direction of his mother. The mother and child were brought closer together. Luke's head was at first level with the Virgin's; in the final painting it is raised slightly above.[33] The differences extend beyond those in the foreground. The fortifications of the inner courtyard were at first smaller. The two figures looking out over the river were smaller, the river itself narrower.[32]

The painting is unusually free of inscriptions; they appear only in the book left open in the room behind Luke, on the ink bottle and in the speech scroll emanating from the ox's mouth. The banderole under the table is blank.[34]

Smith describes the panel in terms of an "exposition of the art of painting", observing that van der Weyden records the essential skills any successful artist should master when claiming to be an heir to St Luke.[17] Luke works on a silverpoint drawing; the preparatory stage of a portrait. This allows him show the artist unencumbered with the paraphernalia of painting, such as an easel, seat or other items which might clutter the composition and place a barrier between the divine and earthly realms.[35]

The positioning of the figures is reversed compared to the van Eyck; the Virgin appears to the dexter (right),[18] a format that was to become predominate in Netherlandish diptychs. van der Weyden switches the colour of their costumes; Luke is dressed in red or scarlet, Mary in warm blues. The Virgin type has further been changed, here she is depicted as a Maria Lactans, with her breasts exposed as she feeds the Christ child. This presentation differs with the Hodegetria (Our Lady of the Way, or She who points the way) Virgin type most usually associated with Byzantine and Northern 15th-century depictions of St Luke. According to art historian Annette de Vries, Mary's breasts represent "redemption of mankind by Christ as human ...[and] spiritual nourishing".[36] Compared to the van Eyck, the approach here is warmer, and emphasises the artist's profession by having Saint Luke draw the Virgin Mary in silverpoint—an exacting medium achievable only with a firm stylus and steady hand—implying the artist's skill and confidence. According to Smith, van der Weyden is displaying his ability, and that "the viewer is invited to compare the drawing, which will be the model for the ultimate picture, with the "flesh and blood" head of the Virgin".[17]

van der Weyden likely saw the original version of the Rolin Madonna at van Eyck's studio before it was collected by its donor. Rolin kept the picture at his private residence and it was neither accessible to the public nor copied at that point. This has formed the basis for the belief that the two painters met, and is in part used to establish a dating of c. 1435; Rogier was then town painter of Brussels and sufficiently well established for such an esteemed audience.

The portrait of Mary is very similar to a 1464 drawing, also in silverpoint, now in the Louvre. Both have been described as of a type van der Weyden was preoccupied with in his drawings; "an ongoing refinement and emphasis on [Mary's] youthfulness … [which is] traceable throughout his work".[37]

Self-portrait

Luke's face is widely considered a self-portrait. He have wised to associates himself with both a saint and the supposed founder of painting. This is reinforced by the fact that Luke is shown drawing, off the cuff, in silver-point; an extremely difficult medium that demands total concentration.[3] If van der Weyden's self-portrait is to be believed, he is in his mid-30s, intelligent and handsome. Later northern artists, including Dirk Bouts and Jan Gossaert, followed his lead, placing self-portraits in depictions of Luke.[38]

Van der Weyden does not hesitate in presenting his ability. Luke's drawing faces outwards so it can be seen clearly by the viewer. The depiction bears a close resemblance to Mary.[3] van der Weyden was careful enough to emphasise this fact that he undertook preparatory sketches in silverpoint on white prepared paper; one of which survives today in the Louvre. The self-portrait accomplishes a number of purposes; the art is paying tribute to his own powers, he is measuring himself against van Eyck, and more generally he is making a case for the legitimacy of the craft of painting.[7] By placing a self-portrait in place of St Luke and showing him drawing rather than painting, van der Weyden, according to De Vries "reveals artistic consciousness by commenting upon artistic traditions and by doing so presents a visual argument for the role and function of the artist and his art, one at that time still predominantly religiously defined."[36]

van der Weyden is known to have inserted a self-portrait into one other work; the lost Justice of Trajan and Herkinbald, known through a tapestry copy held in the Historical Museum of Bern.[39]

Iconography

van der Weyden uses the idea of "the room as sacred space", distinct from the earthly realm, to show the Virgin manifest as a heavenly apparition. This approach is emphasised by the secondary figures, placed at a distance in tightly delineated areas of the pictorial space, while the main figures are positioned in an elevated and idealised room complete with a throne, grand arches and wood carvings. van der Weyden's setting is less artificial than van Eyck's; Luke and Mary face each other as equals, rather than as Shirley Blum describes, "a divinity and a mortal". There is no winged angel holding a crown hovering above the Virgin; such figures are present in the underdrawings, but were eventually abandoned. The landscape is more secular than van Eyck's, not dominated by church spires or a parish church.[40]

The idea of St. Luke painting the Virgin originates from a 3rd-century Marian icon. However, later icons tended to focus on his depiction of the Virgin, rather than him or the event. In the late 13th century, many of the newly emerging institutions of painters guilds were nominating Luke as their patron saint.[25] Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin is among the first known depictions of St Luke in Renaissance art,[41] along with a similar work, a lost triptych panel by Robert Campin.[26] Van der Weyden presents a humanized Virgin and Child, as suggested by the realistic contemporary surroundings,[40] the lack of halos, and the intimate spatial construction. Yet he infuses the panel with extensive religious iconography. A representation of Adam and Eve are carved on the arm-rest of the Virgin's seat.[26] Though Mary is placed under a damask canopy of estate, she does not sit on the bench but rather on its step, an indication of her humility.[42] The throne and canopy indicate her role as Queen of Heaven, although her humility and modesty are referred to by the fact that she sits not on the throne but on its step.[26] The arm-rests of her seat contains figures illusionistically painted as if they were carved into the wood. They depict Adam, Eve and the serpent before the fall from paradise.[16]

The far right of the anteroom shows a writing desk, beneath it a kneeling ox. The animal presumably represents one of the apocalyptic beasts from the Book of Revelation.[26] In the rear, the loggia faces towards a enclosed garden, another emblem of the Virgin's chastity.

Attribution

During the 19th century the painting was variously associated with Quentin Massys and Hugo van der Goes. In the early 20th century, art historians attributed van der Weyden, but were unsure as to which extant panels were original and which were copies.[21] Infrared reflectography has revealed underdrawing in the Boston version which contains heavy redrafting and re-working. This is absent in the other versions, strong evidence the panel is an original.[43] The approach to the underdrawing is very similar to the paintings were attribution to van der Weyden is established, the Descent from the Cross in Madrid, and the Miraflores Altarpiece in Berlin. They are built up with brush and ink, the most attention given to the outlines of the figures and draperies. Hatching is used to indicate areas of deep shadow. In each the underdrawing is a working sketch, subject to constant revisions, which continued even after the painting stage had begun.[44]

Historians gradually revised the painting to earlier in the artist's career, from 1450 to the currently accepted 1435–40. Dendrochronological examination of the growth rings in the wood suggest that the timber was felled around 1424. Around the 15th century, wood was typically stored for around 20 years before use in panel painting, giving an earliest date in mid 1430s. Analysis of the Munich version places it in the 1480s, around 20 years after van der Weyden's death.[45] For some time it was unclear which version was the van der Weyden original. The version in Bruges is in the best condition and of exceptional quality, but dates from c 1491-1510.[32]

The painting's influence was widespread. If it was part of the Guild of Saint Luke's chapel in Brussels, then many near contemporary artists would have viewed and copied it. Fragments and free copies[30] exist in Brussels, Kassel, Valladolid and Barcelona.[46]

Dating

The panel is usually thought completed around 1435. This estimate is based on three factors; the dating of the Rolin Madonna, van der Weyden's opportunity of viewing it, and his ability to produce his work after such a viewing. Rogier is known to have visited Brussels – where van Eyck kept his studio – in 1432 and again 1435. Erwin Panofsky suggested c. 1434 as the earliest possible date, while estimating that the Rolin panel was completed in 1433 or 1434. Julius Held is sceptical of this dating, noting that if we accept it we are "forced to assume that within one year of Jan's work Rogier received a commission which gave him an opportunity to adopt Jan's compositional pattern while subjecting it at the same time to a very thorough and highly personal transformation, and all this in Bruges, under Jan's very eyes".[47]

Held argues for a date between 1440–43, observing that although the painting became highly influential, copies do not appear until mid-century. In addition he sees the work as more advanced than other paintings by the artist from the mid-1430s, writing that it contains "considerable differences" when compared with his other early works, especially the c. 1434 Annunciation Triptych.[48]

Provenance

Despite the eminence of the painting and its many copies, little is known of its provenance before the 19th century. It seems likely that it is the painting Albrecht Dürer mentions in his diary recollection of his visit to the Low Countries in 1520. It is probably the same work recorded in an 1574 inventory of Philip II kept at the Escorial, Madrid.[9]

The painting is recorded in 1835 in the collection of Don Infante Sebastián Gabriel Borbón y Braganza, a grandnephew of Charles III of Spain, himself an artist whose inventory notes attributed the work to Lucas van Leyden and suggested an earlier restoration.[21]

The Boston panel underwent major cleaning and conservation in 1932 and has been subject to restoration at least four times.[21] It is in poor condition, having suffered substantial damage[20] to both frame and surface.

It was donated to the Museum of Fine Arts in 1893 by Henry Lee Higginson in lieu of their New York auction purchase of 1889. The museum held an exhibition in 1989 around the work titled "Art in Context: Rogier van der Weyden's Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin".

Influence

.jpg)

van der Weyden's interpretation was hugely influential during the mid 15th and early 16th centuries, both in free and faithful adaptions. This is reflective of its quality, and the fact that he presents an ideal image of an artist as a self-portrait, legitimising and elevating the trade.[7] Also influential was his madonna type, which he used again for the c. 1450 Diptych of Jean de Gros, which features a 'Virgin and Child' wing directly modeled on his St Luke panel. The implication here is that the artist is presenting her portrait as painted by Saint Luke himself.[49]

From the late 15th century, depictions of Luke drawing the Virgin were widespread, with van der Weyden's panel the earliest known from the Low Countries – Campin's earlier treatment was by then lost.[50] That van der Weyden was so widely copied around this time may be down to Albrecht Dürer's mentioning of the panel in his recount of his visit to Brussels.[51] Most were free copies (adaptions) of van der Weyden's design. The Master of the Legend of St. Ursula incorporated the Maria Lactans type for his Virgin and Child, now in New York. By referencing Luke, artist's could imply that the painting reflected her actual likeness and was thus of great authenticity.[52] Other artists producing works directly influenced by van der Weyden's portrait include by Dieric Bouts, Hugo van der Goes, Derick Baegert and Jan Gossaert. Some artist copied van der Weyden by placing their own likeness in place of St Luke, notably Simon Marmion and Maarten van Heemskerck.[53]

A tapestry version was woven in Brussels c. 1500, now in the Louvre.[54] It was probably designed after a drawing of an inverse of the painting.[55]

References

Notes

- ↑ van Calster, 465

- ↑ van Eyck is credited as the forerunner based on his usual placing as before and influencing Rogier. However a number of art historians have argued both the paintings were completed with the 1934-35 range, and so their lineage may be less than straight forward

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Rothstein, 4

- ↑ Ishikawa (1990), 59

- ↑ Kann, 15

- ↑ Smith, 16

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Harbison (1995), 102

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ainsworth (1998), 139

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 27 December 2014

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Sterling et al, 69

- ↑ Harbison (1995), 10

- ↑ Sterling et al, 66

- ↑ Newman, 135

- ↑ Newman, 136

- ↑ Nash, 157

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Kleiner, 407

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Smith, 21

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Campbell, 21

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Borchert (1997), 78

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Campbell, 54

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Eisler, 73–74

- ↑ van Calster, 477

- ↑ Acres (1999), 25

- ↑ Mcbeth, 118

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Borchert (1997), 64

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Ishikawa (1990), 54

- ↑ Marrow (1999), 54

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Blum, 107

- ↑ Acres, 98

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Borchert (2001), 213

- ↑ Ishikawa (1990), 57

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 van Oosterwijk, Anne. "After Rogier Van der Weyden: Saint Luke drawing the Madonna". vlaamsekunstcollectie.be (Museums of Fine Arts of Antwerp, Bruges, Ghent). Retrieved 18 January 2015

- ↑ Ishikawa (1990), 53

- ↑ Acres, 10

- ↑ Nash, 158

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 de Vries, Annette. "Picturing the Intermediary. Artistic Consciousness in Representations of Saint Luke Painting the Virgin in Netherlandish Art: The Case of Van der Weyden’s Saint Luke". Historians of Netherlandish Art, 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ "Head of the Virgin". Louvre. Retrieved December 05, 2014

- ↑ Brush, 19

- ↑ Koerner, 128

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Blum, 105

- ↑ Hornik and Parsons, 16–17

- ↑ Harbison (1995), 7

- ↑ Spronk, 26

- ↑ Ishikawa (1990), 51

- ↑ Ishikawa (1990), 58

- ↑ Hand et al, 265

- ↑ Held (1955), 225

- ↑ Held (1955), 226

- ↑ Bauman (1986), 49

- ↑ Sterling et al, 73

- ↑ Borchert (2011), 203

- ↑ Bauman (1986), 58

- ↑ Ainsworth (1998), 82

- ↑ Smith, 19

- ↑ Delmarcel, 52

Sources

- Acres, Alfred. "Rogier van der Weyden's Painted Texts". Artibus et Historiae, volume 21, No. 41, 2000

- Ainsworth, Maryan. In: From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum, 1998. ISBN 0-87099-870-6

- Bauman, Guy. "Early Flemish Portraits 1425–1525". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, volume 43, No. 4, Spring, 1986

- Billinge, Rachel; Campbell, Lorne; Dunkerton, Jill; Foister, Susan. "The Materials and Techniques of Five Paintings by Rogier van der Weyden and his Workshop". London: The National Gallery Technical Bulletin, volume 18, 1997

- Blum, Shirley Neilsen. "Symbolic Invention in the Art of Rogier van der Weyden". Journal of Art History, volume 46, issue 1-4, 1977

- Borchert, Till-Holger. "The Case for Corporate Identification". In ''Staint Luke Drawing the Virgin: Selected Essays in Context. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1997. ISBN 2-5035-0572-4

- Borchert, Till-Holger. "Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin", in Van Eyck to Dürer. London: Thames & Hudson, 2011. ISBN 0-5002-3883-7

- Brush, Craig. From the Perspective of Self: Montaigne's Self-portrait. New York: Fordham University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8232-1550-4

- Campbell, Lorne. Van der Weyden. London: Chaucer Press, 2004. ISBN 1-9044-4924-7

- Delmarcel, Guy. Flemish Tapestry from the 15th to the 18th Century. Lannoo, 1999. ISBN 9-0209-3886-X

- De Vos, Dirk. Rogier Van Der Weyden: The Complete Works. New York: Harry N Abrams, 2000. ISBN 0-8109-6390-6

- Eisler, Colin Tobias. New England Museums. Brussels: Centre National de Recherches Primitifs, 1961

- Gardner, Helen; Kleiner, Fred. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: the Western Perspective, Volume 2. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2009. ISBN 0-4955-7364-7

- Kleiner, Fred. "Gardner's Art Through the Ages". Boston: Wadsworth, 2008. ASIN: B00FKYCIWY

- Koerner, Joseph Leo. The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997. ISBN 0-2264-4999-8

- Hand, John Oliver; Metzger, Catherine; Spronk, Ron. Prayers and Portraits: Unfolding the Netherlandish Diptych. National Gallery of Art (U.S.), Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten (Belgium), 2006. CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-12155-5

- Held, Julius. Review of: "Early Netherlandish Painting, Its Origin and Character by Erwin Panofsky". The Art Bulletin, volume 37, No. 3, 1955

- Hornik, Heidi; Parsons, Mikeal Carl. Illuminating Luke: The Infancy Narrative in Italian Renaissance Painting. Continuum, 2003. ISBN 1-5633-8405-1

- Harbison, Craig. The Art of the Northern Renaissance. London: Laurence King Publishing, 1995. ISBN 1-7806-7027-3

- Ishikawa, Chiyo. "Rogier van der Weyden's 'Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin' Reexamined". Boston: Journal of the Museum of Fine Arts. Vol. 2, 1990

- Nash, Susie. Northern Renaissance Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-1928-4269-2

- Purtle Carol (ed). Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin: Selected Essays in Context. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1997. ISBN 2-5035-0572-4

- Rothstein, Bret. Sight and Spirituality in Early Netherlandish Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-5218-3278-0

- Smith, Jeffrey Chipps. The Northern Renaissance (Art and Ideas). London: Phaidon Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7148-3867-5

- Spronk, Ron. "More than Meets the Eye: An Introduction to Technical Examination of Early Netherlandish Paintings at the Fogg Art Museum". Boston: Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin, volume 5, No. 1, Autumn 1996

- Sterling, Charles; Ainsworth, Maryan. "Fifteenth-to Eighteenth-Century European Paintings in the Robert Lehman Collection". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998

- van Calster, Paul. "Of Beardless Painters and Red Chaperons. A Fifteenth-Century Whodunit". Berlin: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. Bd., H. 4, 2003

External links

- Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||