Saint Croix macaw

| Saint Croix macaw | |

|---|---|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Superfamily: | Psittacoidea |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Subfamily: | Arinae |

| Tribe: | Arini |

| Genus: | Ara |

| Species: | A. autocthones[1] |

| Binomial name | |

| Ara autocthones Wetmore, 1937[1] | |

| |

| Sites where fossils of St. Croix Macaw have been found. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ara autochthones (lapsus) | |

The Saint Croix macaw (Ara autocthones)[1] is an extinct species of parrot. The last populations lived on the Caribbean islands Saint Croix and Puerto Rico. It was originally described by Alexander Wetmore in 1937 based on a subfossil limb bone unearthed by L. J. Korn in 1934 from a kitchen midden at an Amerindian archeological site on Saint Croix. A second specimen was described by Storrs L. Olson and Edgar J. Máiz López based on various limb and shoulder bones excavated from a similar site on Puerto Rico, while a possible third specimen from Montserrat has been reported. The species is one of two medium-sized macaws of the Caribbean, the other being the smaller Cuban red macaw (Ara tricolor). Its bones are distinct from Amazon parrots as well as from the other medium-sized but geographically distant Lear's macaw (Anodorhynchus leari) and blue-throated macaw (Ara glaucogularis). The natural range is unknown because parrots were regularly traded between islands by indigenous people. Like other parrot species in the Caribbean, the extinction of the Saint Croix macaw is believed to be linked to the arrival of humans in the region.

Name and etymology

Alexander Wetmore named the species autocthones.[1] An alternative incorrect spelling is autochthones,[2][3] which comes from the Ancient Greek word autochthōn (αὐτός—autos "self" and χθών—chthōn "earth") meaning "born of the earth".[4] Misspellings of a name are termed as lapsus (an accidental misspelling). An obvious error in the original publication containing the description of a species may be corrected by a later "emendation" with suitable justification.[5]

Taxonomy

Wetmore placed the Saint Croix macaw in the macaw genus Ara based on a single tibiotarsus,[1] a placement confirmed by Olson who reexamined the bone.[6] The discovery of a second specimen by Máiz López at Puerto Rico consisting of several bones confirmed this placement.[2] The Saint Croix macaw is distinguished from other macaws because of the intermediate size of the tibiotarsus and carpometacarpus.[2] Olson and Máiz López determined that the size of this species is only comparable to geographically distant macaws, namely the Lear's macaw (Anodorhynchus leari) from Brazil and the blue-throated macaw (Ara glaucogularis) from Bolivia.[2] Their detailed analysis of these and the other bones showed distinct differences from those species, particularly from the genus Anodorhynchus.[2] Based on this, authorities generally recognize the Saint Croix macaw as a valid species.[2][3][7]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Olsonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

wetmore1937was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

The Saint Croix macaw and the smaller Cuban red macaw (Ara tricolor) are the only two Caribbean macaw species that have been described based on physical remains.[3] In addition, seven entirely hypothetical extinct macaw species from various Caribbean islands have been described based only on written accounts.[1][3] Of the hypothetical species, the geographically nearest range is of the Lesser Antillean macaw (Ara guadeloupensis) from Guadeloupe.[1] According to Wetmore, taxonomic affinities with these hypothetical extinct species are unknown.[1]

Description

The subfossil left tibiotarsus (holotype, USNM 483530) described by Wetmore was of an immature but full-grown bird. Wetmore described the bone as similar to the tibiotarsus of Ara tricolor, with a larger transverse width, but more slender compared with larger macaws. The slender proportions of the bone and more elongated ridges about the proximal end distinguish the species from the Amazon parrots.[1]

The bones found by Máiz López (USNM 448344) include the left coracoid (missing a portion of the bone's head), the proximal and distal ends of the left humerus, the proximal end of the right radius, the left carpometacarpus (missing one metacarpal), the left femur (lacking the distal end), the right tibiotarsus (lacking part of the proximal articular surface), and the proximal fragment and worn distal portion of the left tibiotarsus.[2]

Olson and Máiz López examined the bones and showed that they differed from Amazon parrot bones. The tibiotarsus has a narrower internal condyle (the round prominences at the end of a bone) and a distinctive inner cnemial crest (a ridge at the front side of the head) that is more pointed and extends further proximally. The carpometacarpus is proportionally much longer with a process on the alular metacarpal that is not curved proximally. The femur has a proportionally larger head while the ectepicondylar process (a bony elevation) and the attachment of pronator brevis (one of the two pronation muscles in the wing) on the humerus are more proximal. The elongated coracoid has a relatively narrow shaft and the ventral lip of the glenoid facet (equivalent to the glenoid fossa of mammals) is more protruded.[2]

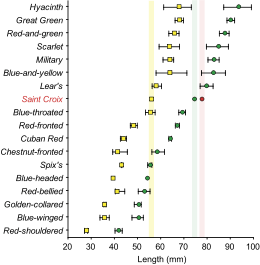

Olson and Máiz López showed that the Saint Croix macaw is within the same size range as the blue-throated macaw and the Lear's macaw. The length of the tibiotarsus is shorter than in the blue-throated macaw but longer than in the Lear's macaw, while the lengths of the coracoid, carpometacarpus, and femur are smaller. In addition to the size, they observed that the pectoral attachment on the humerus is less excavated while the capital groove (a groove separating two parts of the head of the humerus) is wider; the head of the femur is more massive and when seen from the posterior side, more excavated under the head, neck, and trochanter. Furthermore, the more robust shaft of the femur sets it specifically apart from the Lear's macaw while the tibiotarsus is more robust with a flared distal extremity.[2]

Distribution

Bones of the species have been excavated at two islands in the Caribbean, Saint Croix and Puerto Rico. The location at Saint Croix is a pre-Columbian Amerindian village site near the current town of Concordia, near the Southwest Cape.[1] The bones from Puerto Rico were excavated from an inland village of the Saladoid Indians that was located at the eastern bank of the Río Bucaná, north-east of the current city of Ponce.[2] A possible third location is Montserrat, where a nearly complete coracoid was excavated (UF 4416). The bone of this specimen is slightly smaller than the bone of the Puerto Rico specimen, and could therefore be within the range of the Cuban red macaw (Ara tricolor); it has not been assigned to either species.[2]

Although the species had only been found in St. Croix and Puerto Rico, in both cases it was recovered from Amerindian village sites. Williams and Steadman consider it possible that the species may have been native to St. Croix,[3] but Olson and Máiz López regard this as unlikely, noting that parrots, important to the indigenous people, were likely to have been transported between islands. This makes it difficult to determine the natural geographical origins of the parrots known only from subfossil remains found in the West Indian region.[2]

Extinction

The extinction of birds in the Caribbean occurred during three periods. The first period was linked to the sea-level rise after the end of the last ice age. The second period of extinction is linked to the arrival of the Amerindians, while the third extinction period is linked to the arrival of the Europeans.[6] Although the exact causes of the extinction of the Saint Croix macaw are unknown, it is likely related to arrival of the humans in the region.[3] The presence of the bones in kitchen middens suggests that the species was hunted for food.[8] The bones found by Máiz López are dated to about 300 CE, which implies that the extinction of the Saint Croix macaw occurred after that.[2]

Archeological context

The species was originally described by Wetmore based on material excavated in 1934 by L. J. Korn from a pre-Columbian Amerindian kitchen midden (dump for domestic waste) near Concordia, Saint Croix, without specifying the age of the bone.[1]

In 1987, Máiz López found several bones of a single bird at the Hernández Colón archeological site on the eastern bank of the Río Bucaná in south central Puerto Rico [2] The archeological side in the semi-arid southern foothills is a pre-Columbian Saladoid village of approximately 15,000 m2 (3.7 acres) situated on an alluvial terrace.[2] Máiz López found the bones in a kitchen midden in the layer that corresponded with the base and beginning of the Pomarrosa phase,[2] which is stylistically related to the Hacienda Grande ceramic style that lasted globally from about 200 BCE to 400 CE.[9] Radiocarbon dating of charcoal samples indicate that the Pomarrosa phase started locally around 300 CE.[2]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 Wetmore, Alexander (1937). "Ancient records of birds from the island of St. Croix with observations on extinct and living birds of Puerto Rico". The Journal of Agricultural of the University of Puerto Rico 21 (1): 5–16.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Olson, Storrs L.; Edgar J. Máiz López (2008). "New evidence of Ara autochthones from an archeological site in Puerto Rico: a valid species of West Indian macaw of unknown geographical origin (Aves: Psittacidae)" (pdf). Caribbean Journal of Science 44 (2): 215–222.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Williams, Matthew I.; David W. Steadman (2001). "The historic and prehistoric distribution of parrots (Psittacidae) in the West Indies". In Woods, Charles A. and Florence E. Sergile (eds.). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives (pdf) (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 175–189. ISBN 0-8493-2001-1.

- ↑ See:

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "Chthonios". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- Brookes, Ian (editor-in-chief) (2006). The Chambers Dictionary, ninth edition. Edinburgh: Chambers. p. 96. ISBN 0-550-10185-3.

- Nuttall, P. Austin (1869). Dictionary of scientific terms. Strahan & co. p. 45. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ↑ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1999). "Chapter 32: Original spellings". International Code on Zoological Nomenclature. The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Olson, Storrs L. (1978). Gill, F. B, ed. "A paleontological perspective of West Indian birds and mammals" (pdf). Zoogeography in the Caribbean (The 1975 Leidy Medal Symposium): 99–117. "Special Publication 13"

- ↑ Forshaw, Joseph M.; Cooper, William T. (1981) [1973, 1978]. Parrots of the World (corrected second ed.). David & Charles, Newton Abbot, London. p. 368. ISBN 0-7153-7698-5.

- ↑ Nicholls, Steve (2009). Paradise found: nature in America at the time of discovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-226-58340-2.

- ↑ Alegría, R. E. (1965). "On Puerto Rican archaeology". American Antiquity 21: 113–131. JSTOR 2693992. (Subscription required)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||