Saegusa–Ito oxidation

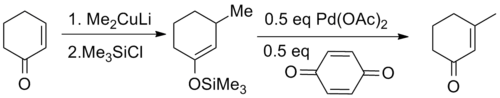

The Saegusa–Ito oxidation is a chemical reaction used in organic chemistry. It was discovered in 1978 by Takeo Saegusa and Yoshihiko Ito as a method to introduce α-β unsaturation in carbonyl compounds.[1] The reaction as originally reported involved formation of a silyl enol ether followed by treatment with palladium(II) acetate and benzoquinone to yield the corresponding enone. The original publication noted its utility for regeneration of unsaturation following 1,4-addition with nucleophiles such as organocuprates.

For acyclic substrates the reaction yields the thermodynamic E-olefin product exclusively.

This discovery was preceded nearly eight years earlier by a report that treatment of unactivated ketones with palladium acetate yielded the same products in low yields.[2] The major improvement provided by Saegusa and Ito was the recognition that the enol form was the reactive species, developing a method based on silyl enol ethers.

Benzoquinone is actually not a necessary component for this reaction; its role is to regenerate palladium(II) from its reduced form palladium(0), so that a smaller amount of expensive palladium(II) acetate is required at the beginning. The reaction conditions and purifications could be easily simplified by just using excess of palladium(II) acetate without benzoquinone, while at a much higher cost.[3][4] Since the reaction typically employs near-stoichiometric amounts of palladium and is therefore often considered too expensive for industrial usage, some progress has been made in the development of catalytic variants.[5][6][7] Despite this shortcoming, the Saegusa oxidation has been used in a number of syntheses as a mild, late-stage method for introduction of functionality in complex molecules.

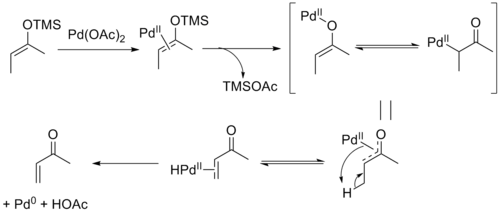

Mechanism

The mechanism of the Saegusa–Ito oxidation involves coordination of palladium to the enol olefin followed by loss of the silyl group and formation of an oxoallyl-palladium complex. β-hydride elimination yields the palladium hydride enone complex which upon reductive elimination yields the product along with acetic acid and Pd0.[8] The reversibility of the elimination step allows equilibration, leading to the thermodynamic E-selectivity in acyclic substrates. It has been shown that the product can form a stable Pd0-olefin complex, which may be responsible for the difficulty with re-oxidation seen in catalytic variants of the reaction.[9]

Scope

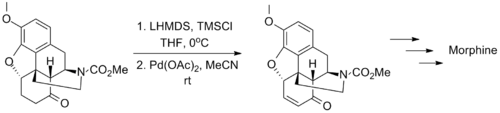

The wide applicability of the Saegusa–Ito oxidation is exemplified by its use in several classic syntheses of complex molecules. The synthesis of morphine by Tohru Fukuyama in 2006 is one such example, in which the transformation tolerates the presence of carbamate and ether substituents.[10]

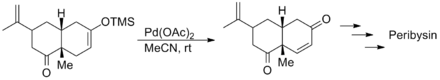

Samuel J. Danishefsky's synthesis of both (+) and (-) peribysin began with a Saegusa–Ito oxidation of the Diels-Alder adduct of carvone and 3-trimethylsilyloxy-1,3-butadiene to yield the enone below. In this case the oxidation tolerated the presence of alkene and carbonyl moieties.[11]

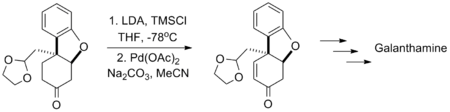

Yong Qiang Tu's synthesis of the Alzheimer's disease medication galanthamine likewise used this reaction in the presence of an acid-sensitive acetal group.[12]

Larry E. Overman's synthesis of laurenyne utilizes a one-pot oxidation with pyridinium chlorochromate followed by a Saegusa oxidation, tolerating the presence of a halogen and a sulfonate.[13]

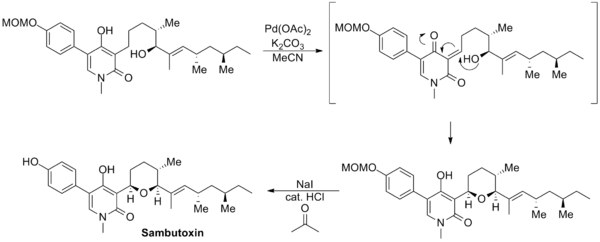

The synthesis of sambutoxin reported by David Williams uses a novel Saegusa–Ito oxidation involving an unprotected enol moiety. The enone product cyclized in situ to regenerate the enol and form the tetrahydropyran ring. Subsequent deprotection of the methoxymethyl group furnished the natural product.[14]

Variations

The vast majority of improvements to this reaction have focused on rendering the transformation catalytic with respect to the palladium salt, primarily due to its high cost. The original conditions, though technically catalytic, still require 50 mol% of palladium(II) actetate, raising the cost to prohibitively high levels for large scale syntheses.

The major advances in catalytic versions of this reaction have steered towards co-oxidants that regenerate the palladium(II) species effectively. Specifically, conditions using atmospheric oxygen as well as stoichiometric allylcarbonate have been developed.

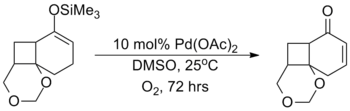

With respect to the former, the method developed by Larock in 1995 represents an environmentally and cost-attractive method as a catalytic substitute for the Saegusa–Ito oxidation.[15]

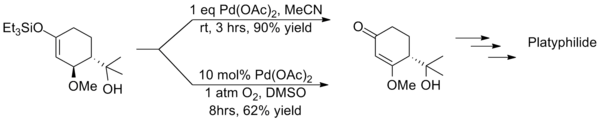

This method suffers from long reaction times and often produces significantly lower yields than the stoichiometric equivalent as showcased in the synthesis of platyphillide by Nishida. The contrast of the two methods highlights the catalytic method's shortcomings.[16]

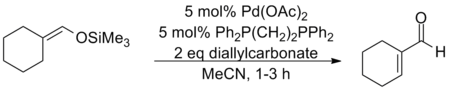

Catalytic variants employing stoichiometric diallylcarbonate and other allylic carbonates have also been developed, primarily by Jiro Tsuji. For these the choice of solvent is essential: nitrile solvents produce the desired enones while ethereal solvents produce α-allyl ketones instead.[17]

This latter method has enjoyed greater success as a synthetic tool, most notably in the Shibasaki total synthesis of the famous poison Strychnine.[18]

Despite these methods, much work remains to be done with regard to catalytic installation of α-β unsaturation.

See also

- Silyl enol ether

- Palladium(II) acetate

- Selenoxide elimination

- Galanthamine total synthesis

- Strychnine total synthesis

References

- ↑ Ito,Yoshihiko; Hirao,Toshikazu; Saegusa,Takeo (1978), Journal of Organic Chemistry 43 (5): 1011–1013, doi:10.1021/jo00399a052 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Theissen, R. J. (1971), Journal of Organic Chemistry 36: 752, doi:10.1021/jo00805a004 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Liu, J.; Lotesta, S. D.; Sorensen, E. J. (2011), Chem. Commun. 47: 1500, doi:10.1039/C0CC04077K, PMC 3156455, PMID 21079876 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Fuwa, H.; Kainuma, N.; Tachibana, K.; Sasaki, M. (2002), J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124: 14983, doi:10.1021/ja028167a Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Lu, Y.; Nguyen, P. L.; Lévaray, N.; Lebel, H. (2013), J. Org. Chem. 78: 776, doi:10.1021/jo302465v Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Gao, W. M.; He, Z. Q.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Y. (2012), Chem. Sci. 3: 883, doi:10.1039/C1SC00661D Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Diao, T. N.; Stahl, S. S. (2011), J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133: 14566, doi:10.1021/ja206575j Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Oxidation, Chem 215 lecture notes

- ↑ Porth, S.; Bats, J. W.; Trauner, D.; Giester, G.; Mulzer, J. (1999), Angewandte Chemie International Edition 38: 2015, doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990712)38:13/14<2015::aid-anie2015>3.0.co;2-# Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Uchida, K.; Yokoshima, S.; Kan, T.; Fukuyama, T. (2006), Organic Letters 8: 5311, doi:10.1021/ol062112m, PMID 17078705 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Angeles, A. R.; Waters, S. P.; Danishefsky, S. J. (2008), Journal of the American Chemical Society 130: 13765, doi:10.1021/ja8048207 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Hu, X.-D.; Tu, Y. Q.; Zhang, E.; Gao, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, A.; Fan, C.-A.; Wang, M. (2006), Organic Letters 8: 1823, doi:10.1021/ol060339b, PMID 16623560 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Overman, L. E.; Thompson, A. S. (1988), Journal of the American Chemical Society 110: 2248, doi:10.1021/ja00215a040 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Williams, D.R.; Tuske, R.A. (2000), "Construction of 4-Hydroxy-2-pyridinones. Total Synthesis of (+)-Sambutoxin", Org. Lett. 2 (20): 3217–3220, doi:10.1021/ol006410+

- ↑ Larock, R. C.; Hightower, T. R.; Kraus, G. A.; Hahn, P.; Zheng, D. (1995), Tetrahedron Letters 36: 2423, doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)00306-w Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Hiraoka, S.; Harada, S.; Nishida, A. (2010), Journal of Organic Chemistry 75: 3871, doi:10.1021/jo1003746 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Tsuji, J.; Minami, I.; Shimizu, I. (1983), Tetrahedron Letters 24: 5635, doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)94160-1 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Ohshima, T.; Xu, Y.; Takita, R.; Shimizu, S.; Zhong, D.; Shibasaki, M. (2002), Journal of the American Chemical Society 124: 14546, doi:10.1021/ja028457r Missing or empty

|title=(help)