SS Californian

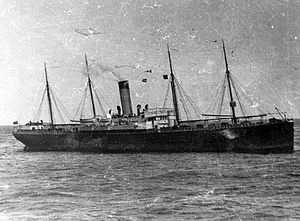

SS Californian on the morning after Titanic sank. | |

| Career (UK) | |

|---|---|

| Name: | SS Californian |

| Namesake: | State of California |

| Owner: |

|

| Route: | Atlantic Ocean crossings |

| Builder: | Caledon Shipbuilding & Engineering Company, Dundee, Scotland |

| Cost: | ₤105,000[1] |

| Yard number: | 159 [1] |

| Christened: | 26 November 1901 |

| Acquired: | 30 January 1902 |

| Decommissioned: | 9 November 1915 |

| Maiden voyage: | 31 January 1902 |

| Fate: | Sunk by German U-boat, 9 November 1915, 61 miles (98 km) southwest of Cape Matapan, Greece. |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Steamship |

| Tonnage: | 6,223 gross, 4,038 net |

| Length: | 447 ft (136 m) LOA |

| Beam: | 53 ft (16 m) |

| Propulsion: | 1 × Triple expansion steam engine 2 × double-ended boilers |

| Speed: | 12.0 knots (22.2 km/h; 13.8 mph) |

| Crew: | 55 Officers and crew |

SS Californian was a Leyland Line steamship that is best known for the controversy surrounding her location during the sinking of the RMS Titanic on 15 April 1912. She was later sunk herself, on 9 November 1915, by a German submarine in the Eastern Mediterranean during World War I.

History

Californian was a British steamship owned by the Leyland Line, part of J.P. Morgan's International Mercantile Marine Co., and was constructed by the Caledon Shipbuilding & Engineering Company in Dundee, Scotland. She measured 6,223 tons, was 447 feet (136 m) long, 53 feet (16 m) at her beam, and had an average full speed of 12 knots (22 km/h). She had a triple expansion steam engine which was powered by two doubled-ended boilers, and was primarily designed to transport cotton, but also had the capacity of carrying 47 passengers and 55 crew members. She was the largest ship built in Dundee up to that time but subsequently larger ships were constructed. Californian was launched on 26 November 1901 and completed her sea trials on 23 January 1902. From 31 January 1902 to 3 March 1902, she made her maiden voyage from Dundee to New Orleans, Louisiana in the United States.

Sinking of Titanic

Stanley Lord, who had commanded Californian since 1911, was her captain when she left Liverpool, England on 5 April 1912 on her way to Boston, Massachusetts. She was not carrying any passengers on this voyage.

On Sunday 14 April at 19:00, Californian's only wireless operator, Cyril Evans, signalled to the Antillian that three large icebergs were five miles to the south. This put them 15 miles (24 km) north of the course the White Star Line passenger ship Titanic was heading. Titanic 's wireless operator Harold Bride also received the warning and delivered it to the ship's bridge at 22:20 that evening while in Latitude 50 degrees 05 minutes North. At Longitude 50 degrees 07 minutes West and steering a course of due west, a position to the south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, Californian encountered a large ice field. Captain Lord spotted it just in time and ordered the helm hard right and the engines full astern. Her head swung rapidly to the right but it was too late; she actually entered the loose margins of the ice field. Lord decided to stop the ship and wait until morning to proceed further. Before going down from the bridge, he thought he saw a ship's light away to the eastward but could not be sure it was not just a rising star. He carried on down to the engineers' cabins and met with the chief whom he told about his plans for stopping. As they were talking, they saw a ship's lights approaching. Lord went to the wireless room to find out if Evans knew of any ships in the area. He met him on the way and informed him that he did: “only the Titanic.” Lord instructed him to call and inform her that Californian was stopped and surrounded by ice.

On deck, Third Officer C.V. Groves also saw the lights of another ship come into view on the horizon 3.5 points above Californian's starboard beam. He first saw it at 11:10pm when 10 or 12 miles away. At the time Californian was heading North East. It finally stopped 6 miles away at 11:40 pm. To him, she was clearly a large liner, as she had multiple decks brightly lit.

Fifteen minutes after spotting the vessel, Groves went below to inform Lord. The latter suggested that the ship be contacted by Morse lamp, which was tried, but no reply was seen.

Titanic 's on-duty wireless operator, Jack Phillips, was busy working off a substantial backlog of personal messages with the wireless station at Cape Race, Newfoundland, 800 miles (1,300 km) away, at the time. When Evans sent the message that they were stopped and surrounded by ice, the relative proximity made Californian's signal loud in Phillips' headphones (both radio operators were using spark gap wireless sets whose signals bled across the radio spectrum and were impossible to tune out). As Evans attempted to transmit his ice message, Phillips was unable to hear a separate, prior message he had been in the process of receiving from Cape Race, and he rebuked Evans with: "Shut up, shut up! I am busy; I am working Cape Race!"[2] Evans listened for a little while longer, and at 23:30 he turned off the wireless and went to bed. Ten minutes later, Titanic hit an iceberg. Ten minutes after that, her lookout, Frederick Fleet, spotted a nearby ship. She sent out her first distress call 25 minutes later.

Slightly after midnight Second Officer Herbert Stone took watch from Groves. He, too, tried signalling the ship with the Morse lamp, also without success. Around 00:45 on 15 April, he saw a white flash appear from the direction of the nearby ship. First he thought it was a shooting star, until he saw another one. He saw five rockets before being joined by the apprentice. He called down the speaking tube to Captain Lord at 1:15, but it is unclear how many rockets he told him about. Lord asked if they had been a company signal. Stone said he didn’t know. Lord told Stone to tell him if anything about the ship changed, to keep signaling it with the Morse lamp, but did not request that it be contacted by wireless. Regulations of the time specified rockets (of any color) firing at one-minute intervals would signal distress. As fired from "Titanic", at irregular and longer term intervals, there may have been considerable doubt as to their meaning. They later dismissed it as a celebration of some kind.

At the British inquiry following the Titanic disaster, Stone and apprentice officer James Gibson admitted to snippets of the conversation that they had had during their watch that night. "A ship is not going to fire rockets at sea for nothing," Stone said, and also, "Have a look at her now. She looks very queer out of the water — her lights look queer."[2] Gibson observed, "She looks rather to have a big side out of the water" and he agreed that "everything was not all right with her;" that it was "a case of some kind of distress."

By 2:00 the ship appeared to be leaving the area. A few minutes later Gibson informed Captain Lord as such and that eight white rockets had been seen. Lord, who said that he had been asleep (and later claimed no recollection of the visit), asked whether they were sure of the color. Gibson said yes and left.

At 2:20, Titanic sank. Around 3:30 Stone and Gibson, still sharing the middle watch, spotted rockets to the south. They did not see the ship that was firing them, but at about this same time the rescue ship Carpathia was racing up from the southeast, firing rockets to let Titanic know that help was on the way. At 4:16, Chief Officer George F. Stewart relieved Stone, and almost immediately noticed, coming into view from the south, a brilliantly lighted, four-masted steamship with one funnel. This would later prove to be Carpathia.

Lord woke up at 4:30 and went out on deck to decide how to proceed past the ice to the west. At 5:30, acting on his own initiative, Stewart woke Evans (the wireless operator), and asked him to find out why a ship had fired rockets during the night. He turned on the wireless and found out that Titanic had sunk overnight. Stewart took the news to Captain Lord who ordered the ship underway. However, instead of proceeding south through clear water to Titanic's last reported position, he ordered her to head west and into the ice floe. After passing slowly through it, she reached clear water, increased speed, and finally turned south. She actually passed the Carpathia to the east, then turned, and headed northeast back towards the rescue ship, arriving at 8:30. Lord later explained that this convoluted route was due to ice conditions, even though there was clear water between his original position and Titanic’s reported position.

Carpathia was just finishing picking up the last of Titanic's survivors. After communication between the two ships, Carpathia left the area leaving Californian to search for any other survivors, but it only found scattered wreckage and empty lifeboats.

Captain Lord has been accused of being downright unwilling to adjust to a new situation. He had, like any other captain, his own ship and crew to be mindful of, hence his decision to stay stopped for the night owing to the vast amounts of ice in the ocean, which, it is said, was indeed an act of prudence. It is also said, however, that this constituted no reason for a good mariner to do nothing upon learning of the distress rockets. He was presented with a new situation that night, and, had he increased his lookouts, he would have safely made it to the scene - or without any serious risks, if anything. According to the British inquiry, if it had acted upon the rockets and pushed through the ice, the Californian "might have saved many if not all of the lives that were lost".[3] Captain Lord was also criticized at the American inquiry for his failure to respond to the rockets.[4]

Aftermath

As public knowledge grew of the Titanic disaster, questions soon arose on how the disaster occurred, as well as if and how it could have been prevented.

An American inquiry started on 19 April, the day Californian arrived unnoticed in Boston. Initially, the world was unaware of her and her part in the Titanic disaster. On 22 April, the inquiry discovered that a ship near Titanic had failed to respond to the distress signals. The identity of the ship was unknown.

The next day, a small newspaper in New England, the Daily Item, printed a shocking story claiming that Californian had refused aid to Titanic. The source for the story was her carpenter, James McGregor, who stated that she had been close enough to see Titanic’s lights and distress rockets. By sheer coincidence, on the same day, the Boston American printed a story sourced by her assistant engineer, Ernest Gill, which essentially told the same story as the Daily Item.

Lord also spoke with Boston area newspapers. In one article on 19 April (Boston Traveler), Lord claimed that his ship was thirty miles from Titanic, but in the Boston Post of the 22 April he claimed twenty miles. He told the Boston Globe that his ship had spent three hours steaming around the wreck site trying to render assistance, but Third Officer Grove later stated that the search ended after two hours, at 10:30. When reporters asked Lord about his exact position the night of the disaster, he refused, calling such information state secrets. He also claimed that he did not use the wireless because his ship had been stopped, and thus the wireless was not working. In fact, only her engines were stopped. She was under steam the whole night (for electricity and heating) and the wireless only needed to be turned on.

After the newspaper revelations on 23 April, the American inquiry subpoenaed Gill, as well as Captain Lord and others from Californian. During his testimony, Gill repeated his claims. Lord’s testimony was conflicting and changing. For example, he detailed three totally different ice conditions. He admitted knowing about the rockets (after telling Boston newspapers that his ship had not seen any rockets) but insisted that they were not distress rockets, and were not fired from Titanic but a small steamship, the so-called “third ship” of the night.

Yet, the testimony of Captain J. Knapp, U.S. Navy, and a part of the Navy Hydrographer’s Office, made clear that Titanic and Californian were in sight of each other, and that no third vessel had been in the area.

The so-called scrap log of Californian also came under question. This is a log where all daily pertinent information is entered before being approved by the captain and entered into the official log. Yet the scrap log was missing. In an extraordinary omission, the official log (written after the disaster) never mentioned a nearby ship, or rockets. However, at the British Inquiry, in an equally extraordinary omission, the second officer of Californian was never asked to recall the notations he had actually written in it, during his bridge-watch between midnight and 4:00 on 15 April.

On 2 May, the British Court of Formal Investigation began. Again, Lord gave conflicting, changing, and evasive testimony. By way of contrast, the captain of Carpathia, at each inquiry, gave consistent and forthright testimony. It is significant that, during the British Inquiry, Captain Arthur Rostron of Carpathia was asked to confirm an affidavit he had made to the United States Inquiry. Among the other things in his affidavit, he confirmed that "It was daylight at about 4.20 a.m. At 5 o'clock it was light enough to see all around the horizon. We then saw two steamships to the northwards, perhaps 7 or 8 miles distant. Neither of them was 'Californian.'".[5]

During the inquiry, the crew of Californian also gave conflicting testimonies. Most notably, Captain Lord said he was not told that the nearby ship had disappeared, contradicting testimony from James Gibson who said he reported it and that Lord had acknowledged him.

Also during the inquiries, survivors of Titanic recalled seeing the lights of another ship that was spotted after she had hit the iceberg. To her Fourth Officer Boxhall the ship appeared to be off her bow, five miles (8 km) away and heading in 'her direction. Just like Californian's officers, Boxhall attempted signaling the ship with a Morse lamp, but received no response.

Titanic's Captain Edward Smith had felt the ship was close enough that he ordered the first lifeboats launched on the port side to row over to the ship, drop off the passengers, and come back to Titanic for more. The lights of the ship were seen from her lifeboats throughout the night; one rowed towards them, but never seemed to get any closer.

Both the American and British inquires found that Californian must have been closer than the 19 1⁄2 miles (31.4 km) claimed by Lord, and that both ships were visible from the other. Indeed, when Carpathia arrived at the wreck site, a vessel was clearly seen to the north; this was later identified as Californian. Both inquiries concluded that Captain Lord failed to provide proper assistance to Titanic and the British Inquiry further concluded that had Californian responded to Titanic's rockets and gone to assist, that it "...might have saved many if not all of the lives that were lost." Later, careful study indicated that had Californian properly responded there would have still been a great loss of life but that perhaps three hundred additional lives might have been saved.

In the months and years following the disaster, numerous preventative safety measures were enacted. The United States passed the Radio Act of 1912, which required 24–hour radio watch on all ships in case of an emergency. The first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea formed a treaty that also required 24–hour radio monitoring and standardized the use of distress rockets.

After the publication of A Night to Remember, captain Lord sought a re-hearing of the Inquiry relating to his ship to counter the allegations made in the book.[6] Petitions presented to the UK Government in 1965 and 1968 by the Mercantile Marine Service Association (MMSA), a union to which Captain Lord belonged, failed to get the matter re-examined.

As a result of Ballard's expedition showing that Titanic was not in the position determined in the original investigation, the Board of Trade ordered a re-examination.[7] In 1992, the British Government's Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) concluded its "Reappraisal of Evidence Relating to the SS Californian." The conclusions of the MAIB report were those of Deputy Chief Inspector, James de Coverly. The MAIB report stated: "What is significant, however, is that no ship was seen by the Titanic until well after the collision...watch was maintained with officers on the bridge and seamen in the crow’s nest, and with their ship in grave danger the lookout for another vessel which could come to their help must have been most anxious and keen.

"It is in my view inconceivable that the Californian or any other ship was within the visible horizon of the Titanic during that period; it equally follows that the Titanic can't have been within the Californian’s horizon." The report went on: "More probably, in my view, the ship seen by Californian was another, unidentified, vessel."

The original investigator of the 1992 reappraisal was a Captain Barnett. He had concluded "that the Titanic was seen by the Californian and indeed kept under observation from 23:00 or soon after on 14 April until she sank," and that "he bases this view on the evidence from Captain Lord and the two watch officers." It was after Barnett's original report was submitted that Captain de Coverly was given the task of further examination. Both Barnett and de Coverly had concluded that Titanic's rockets had been seen and that Officer Stone and Captain Lord had not responded appropriately to signals of distress. The 1992 Marine Accident Investigation Branch report concluded that Captain Lord and his crew's actions "fell far short of what was needed".

Captain Lord's chief defender and union attorney, Leslie Harrison, who had led the fight to have Californian incident re-examined by the British government, called the dual conclusions of the report "an admission of failure to achieve the purpose of the reappraisal." Internally, however, the working files of the MAIB reveal that both authors of the report agreed that Titanic and Californian were in sight of each other; the contradictory conclusions can be attributed to the writing of the report being delegated to a junior member of the branch, possibly due to the high workload of the MAIB at the time. This could explain some of the inept research, such as references to Samson being the mystery ship seen by Titanic (despite this being debunked in the 1960s) and bizarre conclusions regarding the nature of ocean currents in the vicinity of Titanic wreck site.

The findings of the MAIB remain the official position of the British Government, as reflected in replies to Parliamentary Questions in the years since.

To this day there are defenders of Captain Lord, yet two conclusions are incontrovertible. First, if he had simply requested that the wireless be turned back on, the mysteries of the night would have been clarified instantly. Second, at both inquiries, he admitted he knew that rockets had been fired. In 1912, it was understood by all seamen that rockets being fired in sequence, no matter their color, were to be interpreted as a distress signal and that aid should be rendered . As author Daniel Allen Butler wrote: “The crime of Stanley Lord was not that he may have ignored the Titanic’s rockets, but that he unquestionably ignored someone’s cry for help.” Still, "Titanic's" out-of-sequence firing of rockets could have given cause to doubt distress. The manner in which they were fired would officially have meant navigation difficulty, asking to please stand by.

World War I

Californian continued normal service until World War I, when the British government took control of her.

On 9 November 1915, while en route from Salonica to Marseilles, she was torpedoed and sunk approximately 60 miles (50 nmi; 100 km) south-southwest of Cape Matapan, Greece by the German U-boat U-35, killing one person. As of 2015, Californian's wreck has not been found and discovered.[8] The Californian went down less than 200 miles (170 nmi; 320 km) from the location where the HMHS Britannic, Titanic's sister ship, would sink just over a year later.

Notes

- Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Caledon Built - Dundee Ships", Friends of Dundee City Archives

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lord, Walter; "A Night to Remember", (1955), St. Martin's Griffin, 2005

- ↑ "Circumstances in Connection with the SS Californian", British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry (titanicinquiry.org)

- ↑ titanicinquiry.org

- ↑ British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry Day 28 Question 25551

- ↑ MAIB report p1

- ↑ MAIB report p2

- ↑ Tennent, A.J. (2006). British Merchant Ships Sunk by U-boats in World War One. Periscope Publishing. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-904381-36-5.

- References used

- "Caledon Built - Dundee Ships" (PDF). Friends of Dundee City Archives. Friends of Dundee. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Lord, Walter (1955). A Night to Remember (2005 ed.). New York, New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-8050-7764-3.

Further reading

- Lee, Paul. The Indifferent Stranger, electronic book, 2008.

- Eaton, John P. and Haas, Charles A. Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1995.

- Lord, Walter. The Night Lives On. Morrow and Company, 1986.

- Reade, Leslie. The Ship That Stood Still: The Californian and Her Mysterious Role in the Titanic Disaster. W. W. Norton & Co Inc, 1993.

- Lynch, Donald and Marschall, Ken. Titanic: An Illustrated History. Hyperion, 1995.

- Molony, Senan. Titanic and the Mystery Ship. Tempus Publishing, 2006.

- Padfield, Peter. The Titanic and the Californian. The John Day Company, 1965.

- Butler, Daniel Allen. The Other Side of the Night. Casemate, 2009.

External links

- Californian Crew List with Biographies

- Captain Stanley Lord

- SS Californian

- A PV Solves a Puzzle by Senan Molony

- The Californian Incident, A Reality Check

- MAIB Reappraisal of Evidence

- The Titanic and the Californian

Coordinates: 35°32′30″N 22°06′06″E / 35.54167°N 22.10167°E