Rydberg matter

Rydberg matter is a phase of matter formed by Rydberg atoms; it was predicted around 1980 by É. A. Manykin, M. I. Ozhovan and P. P. Poluéktov.[1][2] It has been formed from various elements like caesium,[3] potassium,[4] hydrogen[5][6] and nitrogen;[7] studies have been conducted on theoretical possibilities like sodium, beryllium, magnesium and calcium.[8] It has been suggested to be a material that diffuse interstellar bands may arise from;[9] circular[10] Rydberg states, where the outermost electron is found in a planar circular orbit, are the most long-lived with lifetimes of up to several hours[11] and are the most common.[12][13][14] This hypothesis, however, is disputed and is not generally accepted by the astronomical community.

Physical

Rydberg matter consists of usually[16] hexagonal[17][15] planar[18] clusters; these cannot be very big because of the retardation effect caused by the finite velocity of the speed of light.[18] Hence, they are not gases or plasmas; nor are they solids or liquids; they are most similar to dusty plasmas with small clusters in a gas. Though Rydberg matter can be studied in the laboratory by laser probing,[19] the largest cluster reported consists of only 91 atoms,[6] but it has been shown to be behind extended clouds in space[9][20] and the upper atmosphere of planets.[21] Bonding in Rydberg matter is caused by delocalisation of the high-energy electrons to form an overall lower energy state.[2] The way in which the electrons delocalise is to form standing waves on loops surrounding nuclei, creating quantised angular momentum and the defining characteristics of Rydberg matter. It is a generalised metal by way of the quantum numbers influencing loop size but restricted by the bonding requirement for strong electron correlation;[18] it shows exchange-correlation properties similar to covalent bonding.[22] Electronic excitation and vibrational motion of these bonds can be studied by Raman spectroscopy.[23]

Lifetime

Due to reasons still debated by the physics community because of the lack of methods to observe clusters,[26] Rydberg matter is highly stable against disintegration by emission of radiation; the characteristic lifetime of a cluster at n = 12 is 25 seconds.[25][27] Reasons given include the lack of overlap between excited and ground states, the forbidding of transitions between them and exchange-correlation effects hindering emission through necessitating tunnelling[22] that causes a long delay in excitation decay.[24] Excitation plays a role in determining lifetimes, with a higher excitation giving a longer lifetime;[25] n = 80 gives a lifetime comparable to the age of the Universe.[28]

Excitations

| n | d (nm) | D (cm−3) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.153 | 2.8×1023 |

| 4 | 2.45 | |

| 5 | 3.84 | |

| 6 | 5.52 | |

| 10 | 15.3 | 2.8×1017 |

| 40 | 245 | |

| 80 | 983 | |

| 100 | 1534 | 2.8×1011 |

In ordinary metals, interatomic distances are nearly constant through a wide range of temperatures and pressures; this is not the case with Rydberg matter, whose distances and thus properties vary greatly with excitations. A key variable in determining these properties is the principal quantum number n that can be any integer greater than 1; the highest values reported for it are around 100.[28][29] Bond distance d in Rydberg matter is given by

where a0 is the Bohr radius. The approximate factor 2.9 was first experimentally determined, then measured with rotational spectroscopy in different clusters.[15] Examples of d calculated this way, along with selected values of the density D, are given in the table to the right.

Condensation

Like bosons that can be condensed to form Bose–Einstein condensates, Rydberg matter can be condensed, but not in the same way as bosons. The reason for this is that Rydberg matter behaves similar to a gas, meaning that it cannot be condensed without removing the condensation energy; ionisation occurs if this is not done. All solutions to this problem so far involve using an adjacent surface in some way, the best being evaporating the atoms of which the Rydberg matter is to be formed from and leaving the condensation energy on the surface.[30] Using caesium atoms, graphite-covered surfaces and thermionic converters as containment, the work function of the surface has been measured to be 0.5eV,[31] indicating that the cluster is between the ninth and fourteenth excitation levels.[24]

See also

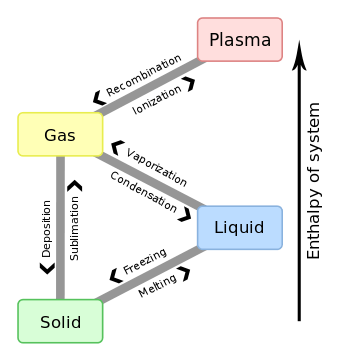

- State of matter

- The Journal of Cluster Science has dedicated in 2012 a special issue (Volume 23, Issue 1) to “Rydberg-Matter and Excited-State Clusters”.[32]

- The President of Russian Academy of Sciences Vladimir Fortov has recently noted the works on Rydberg Matter as a great scientific event [33]

References

- ↑ É.A. Manykin, M.I. Ozhovan, P.P. Poluéktov (1980). "Transition of an excited gas to a metallic state". Sov. Phys. Tech. Phys. Lett. 6: 95.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 É.A. Manykin, M.I. Ozhovan, P.P. Poluéktov; Ozhovan; Poluéktov (1981). "On the collective electronic state in a system of strongly excited atoms". Sov. Phys. Dokl. 26: 974–975. Bibcode:1981SPhD...26..974M.

- ↑ V.I. Yarygin, V.N. Sidel’nikov, I.I. Kasikov, V.S. Mironov, and S.M. Tulin (2003). "Experimental Study on the Possibility of Formation of a Condensate of Excited States in a Substance (Rydberg Matter)". JETP Letters 77 (6): 280. Bibcode:2003JETPL..77..280Y. doi:10.1134/1.1577757.

- ↑ S. Badiei and L. Holmlid (2002). "Neutral Rydberg Matter clusters from K: Extreme cooling of translational degrees of freedom observed by neutral time-of-flight". Chemical Physics 282: 137–146. Bibcode:2002CP....282..137B. doi:10.1016/S0301-0104(02)00601-8.

- ↑ S. Badiei and L. Holmlid (2006). "Experimental studies of fast fragments of H Rydberg matter". Journal of Physics B 39 (20): 4191–4212. Bibcode:2006JPhB...39.4191B. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/39/20/017.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 J. Wang; Holmlid, Leif (2002). "Rydberg Matter clusters of hydrogen (H2)N* with well-defined kinetic energy release observed by neutral time-of-flight". Chemical Physics 277 (2): 201. Bibcode:2002CP....277..201W. doi:10.1016/S0301-0104(02)00303-8.

- ↑ S. Badiei and L. Holmlid (2002). "Rydberg Matter of K and N2: Angular dependence of the time-of-flight for neutral and ionized clusters formed in Coulomb explosions". International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 220 (2): 127. Bibcode:2002IJMSp.220..127B. doi:10.1016/S1387-3806(02)00689-9.

- ↑ A.V. Popov (2006). "Search for Rydberg matter: Beryllium, magnesium and calcium". Czechoslovak Journal of Physics 56: B1294. Bibcode:2006CzJPh..56B1294P. doi:10.1007/s10582-006-0365-2.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 L. Holmlid (2008). "The diffuse interstellar band carriers in interstellar space: All intense bands calculated from He doubly excited states embedded in Rydberg Matter". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 384 (2): 764–774. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.384..764H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12753.x.

- ↑ J. Liang, M. Gross, P. Goy, S. Haroche (1986). "Circular Rydberg-state spectroscopy". Physical Review A 33 (6): 4437–4439. Bibcode:1986PhRvA..33.4437L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.33.4437. PMID 9897204.

- ↑ R.L. Sorochenko (1990). "Postulation, detection and observations of radio recombination lines". In M.A. Gordon, R.L. Sorochenko. Radio recombination lines: 25 years of investigation. Kluwer. p. 1. ISBN 0-7923-0804-2.

- ↑ L. Holmlid (2007). "Direct observation of circular Rydberg electrons in a Rydberg Matter surface layer by electronic circular dichroism". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 19 (27): 276206. Bibcode:2007JPCM...19A6206H. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/19/27/276206.

- ↑ L. Holmlid (2007). "Stimulated emission spectroscopy of Rydberg Matter: observation of Rydberg orbits in the core ions". Applied Physics B 87 (2): 273–281. Bibcode:2007ApPhB..87..273H. doi:10.1007/s00340-007-2579-9.

- ↑ L. Holmlid (2009). "Nuclear spin transitions in the kHz range in Rydberg Matter clusters give precise values of the internal magnetic field from orbiting Rydberg electrons". Chemical Physics 358: 61–67. Bibcode:2009CP....358...61H. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.12.019.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 L. Holmlid, "Rotational spectra of large Rydberg Matter clusters K37, K61 and K91 give trends in K-K bond distances relative to electron orbit radius". J. Mol. Struct. 885 (2008) 122–130.

- ↑ L. Holmlid, "Clusters HN+ (N = 4, 6, 12) from condensed atomic hydrogen and deuterium indicating close-packed structures in the desorbed phase at an active catalyst surface". Surf. Sci. 602 (2008) 3381–3387.

- ↑ L. Holmlid, "Precision bond lengths for Rydberg Matter clusters K19 in excitation levels n = 4, 5 and 6 from rotational radio-frequency emission spectra". Mol. Phys. 105 (2007) 933–939.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 L. Holmlid, "Classical energy calculations with electron correlation of condensed excited states – Rydberg Matter". Chem. Phys. 237 (1998) 11–19. doi:10.1016/S0301-0104(98)00259-6

- ↑ H. Åkesson, S. Badiei and L. Holmlid, "Angular variation of time-of-flight of neutral clusters released from Rydberg Matter: primary and secondary Coulomb explosion processes". Chem. Phys. 321 (2006) 215–222.

- ↑ L. Holmlid, "Amplification by stimulated emission in Rydberg Matter clusters as the source of intense maser lines in interstellar space". Astrophys. Space Sci. 305 (2006) 91–98.

- ↑ L. Holmlid, "The alkali metal atmospheres on the Moon and Mercury: explaining the stable exospheres by heavy Rydberg Matter clusters". Planet. Space Sci. 54 (2006) 101–112.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 E.A. Manykin, M.I. Ojovan, P.P. Poluektov. "Theory of the condensed state in a system of excited atoms". Sov. Phys. JETP 57 (1983) 256–262.

- ↑ L. Holmlid, "Vibrational transitions in Rydberg Matter clusters from stimulated Raman and Rabi-flopping phase-delay in the infrared". J. Raman Spectr. 39 (2008) 1364–1374.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 É. A. Manykin, M. I. Ozhovan, P. P. Poluéktov, "Decay of a condensate consisting of excited cesium atoms". Zh. Éksp. Teor. Fiz. 102, 1109 (1992) [Sov. Phys. JETP 75, 602 (1992)].

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 E.A. Manykin, M.I. Ojovan, P.P. Poluektov. "Impurity recombination of Rydberg matter". JETP 78 (1994) 27–32.

- ↑ Holmlid, Leif (2002). "Conditions for forming Rydberg matter: condensation of Rydberg states in the gas phase versus at surfaces". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 14 (49): 13469. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/14/49/305.

- ↑ I. L. Beigman and V. S. Lebedev, "Collision theory of Rydberg atoms with neutral and charged particles". Phys. Rep. 250, 95 (1995).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 L. Holmlid, "Redshifts in space caused by stimulated Raman scattering in cold intergalactic Rydberg Matter with experimental verification". J. Exp. Theor. Phys. JETP 100 (2005) 637–644.

- ↑ Badiei, Shahriar; Holmlid, Leif (2002). "Magnetic field in the intracluster medium: Rydberg matter with almost free electrons". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 335 (4): L94. Bibcode:2002MNRAS.335L..94B. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05911.x.

- ↑ J. Wang, K. Engvall and L. Holmlid, "Cluster KN formation by Rydberg collision complex stabilization during scattering of a K beam off zirconia surfaces". J. Chem. Phys. 110 (1999) 1212–1220.

- ↑ R. Svensson and L. Holmlid, "Very low work function surfaces from condensed excited states: Rydberg matter of cesium". Surface Sci. 269/270 (1992) 695–699.

- ↑ http://rd.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10876-012-0449-z

- ↑ http://itar-tass.com/opinions/interviews/1853

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||