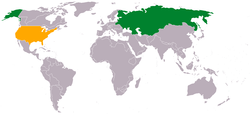

Russian Empire–United States relations

|

|

Russia |

United States |

|---|---|

The relations between the Russian Empire and the United States of America (1776–1922) predate the Soviet Union–United States relations (1922–1991) and the Russia–United States relations (1991–present). Relations between the two countries were established in 1776.

Establishment of relations (1776)

The relations between the two states are usually considered to have begun in 1776, when the United States of America declared its independence from the British Empire and became a state. Earlier contacts had occurred between Americans and Russians however: In 1698, Peter the Great and William Penn had met in London, and in 1763 a Boston merchant had anchored his ship at the port of Kronstadt after a direct transatlantic voyage.

Russian involvement in the American Revolutionary War

Despite being geographically removed from the American colonies, Russia under Catherine the Great significantly affected the American Revolution through trade and diplomacy. While Catherine personally oversaw most of Russia’s interactions with the American colonies, Britain and the other nations directly or indirectly involved in the Revolutionary War, she also entrusted certain tasks to her foreign advisor Nikita Panin, who often acted on Catherine’s behalf when it came to matters of international diplomacy. Catherine and Panin interacted with the British government through James Harris, an Earl at the Russian court.[1] The decisions made by Catherine and Panin during the Revolution to continue trade with the colonies, remain officially neutral, refuse Britain’s requests for military assistance, and insist on peace talks that linked a resolution of the American Revolution with the settlement of separate European conflicts indirectly helped the Americans win the Revolution and gain their freedom.

Trade with the colonies

Although a violation of Britain’s Navigation Acts, which did not allow the American colonies to establish autonomous trade connections, direct trade between Russia and the colonies began as early as 1763. Russian products such as hemp, sail linen and iron started arriving in colonial ports years before the Revolutionary War began and did not stop once the war started.[2] The colonists and Russia saw each other as excellent trading partners, particularly because both parties had ample resources to offer. Continued trade with Russia during the Revolution provided the colonies with markets for their products as well as funds and supplies necessary to survive.

Throughout the Revolutionary War, Catherine believed an independent American nation would be ideal for Russian business interests. While some Russian leaders worried that an independent America might interfere with Russia’s trade with other European nations, Catherine saw direct Russo-American trade as an excellent opportunity to expand commerce. Catherine knew that after the Revolution, a free America could trade directly with Russia without interference. Moreover, if the colonies gained their freedom, Britain would have to turn to other countries - such as Russia - to supply it with the resources it could no longer simply extract from the American colonies.[3]

Neutrality

Catherine chose to have Russia remain officially neutral during the Revolution, never openly picking sides in the war.[4] On an unofficial basis, however, she acted favorably towards the American colonists, by offering to provide them anything she could without compromising Russia’s neutrality and her eventual desire to act as a mediator.

In March 1780, the Russian ministry released a "Declaration of Armed Neutrality.” This declaration set out Russia's international stance on the American Revolution, focusing mainly on the importance of allowing neutral vessels to travel freely to any Russian port without being searched or harassed by the Navigation Acts. While the declaration kept Russia officially neutral, it supported many of France's own pro-colonial policies and badly damaged Britain’s efforts to strangle the colonies through naval force. The declaration also gave the American rebels an emotional lift, as they realized Russia was not solidly aligned with Britain.[5] With Russia as a potential, powerful friend, Russo-American connections and communications continued to improve. Nevertheless, Catherine refused to openly recognize the colonies as an independent nation until the war ended.[6]

Britain's requests for assistance

As the Revolutionary War continued into the late 1770s, a growing list of European powers took sides against Britain. The British Ministry saw the need to solidify an alliance with Russia to bolster its war with the colonies. As a world power that had allied with Britain in the past, the Russians were an obvious choice to assist Britain with logistical and military support, as well as diplomatic efforts.[7] While Catherine seems to have admired the British people and their culture, she disliked Britain’s King George and his ministry. She was particularly disturbed by the Seven Years' War, during which Catherine observed Britain’s efforts to discreetly exit the conflict and leave Russia's Prussian allies vulnerable to defeat. She considered these efforts immoral and disloyal, and saw Britain as an unreliable ally. She also viewed the American Revolution as Britain’s fault. Citing the constant change in Britain’s ministries as a major reason for the problems with colonial governance, Catherine understood the colonies’ grievances.[8] Despite Russia’s official neutrality, Catherine’s negative opinions of British rule and her view that Britain caused the war with the colonies weighed on her decisions when Britain began to request Russian support. In the summer of 1775, Britain sent diplomats to Russia in an attempt to learn whether Catherine would agree to send troops to America to aid British forces. Although her initial response seemed positive, Catherine denied King George’s formal request for support. While her dislike of the British ministry likely influenced her decision, Catherine formally cited the fact that her army needed rest after having just finished more than six years of war.[9]

In November 1779, Britain made another plea for Russian assistance. Swallowing their pride, the British ministry acknowledged to Catherine the collective power of Britain’s enemies, as well as the King’s desire for peace. The British ministry's letter to Catherine explained these concerns and offered to “commit her [Britain’s] interests to the hand of the Empress.”[10] The British included a specific request that Russia use force against all British enemies, including other European countries, to stop the American Revolution. After waiting several months, Catherine decided to refuse Britain’s request.[11] In 1781, Britain attempted to bribe Russia to gain its assistance. Distressed and realizing that they were close to losing the war and their American colonies, James Harris asked if a piece of British territory could convince Russia to join the fight on the side of England. Offering the island of Minorca, Harris did not request soldiers in exchange; this time Britain simply asked that Russia convince France to exit the war and force the American rebels to fight alone. Perhaps revealing her secret desire to have the American colonists gain their independence, Catherine used Harris' proposal to embarrass Britain. She declined Harris’ offer and published Britain’s attempts at bribery to the French and Spanish.[12]

Attempt at peace-making

Catherine played a significant role in peacemaking efforts during the Revolutionary War. In October 1780, she sent a proposal to each of the European powers involved in the conflict. The proposal requested that the countries meet to discuss what could be done to create peace. The powers met in Vienna after Britain requested the Austrian ministry co-mediate the peace talks. Catherine sent Prince Dimitri Galitzin to act on her behalf as the Russian mediator. She sent him with a proposed set of peace guidelines that included a multi-year armistice between the countries and a requirement that there be negotiations between Britain and their European enemies as well as between Britain and America. Catherine chose not to include a proposal concerning whether America would become autonomous. Since the British would not accept American independence and the French would not accept anything short of it, Catherine realized that explicitly providing for either outcome would lead to an immediate breakdown in the talks.[13] Catherine’s ambiguous negotiation efforts ultimately fell through.

19th century

In 1801 Thomas Jefferson appointed Levett Harris as the first American consul-general to Russia (1803-1816).[14][15]

The Monroe Doctrine was partly aimed at Holy Alliance support of intervention in Latin America, as well as the Ukase of 1821 banning non-Russian ships from the Northwest Coast. The Russo-American Treaty of 1824 set parallel 54°40′ north as the boundary between Russian America and the Anglo-American Oregon Country.

American Civil War

During the American Civil War, Russian-American relations were very good. Alone among European powers Russia offered rhetorical support for the Union, largely due to the view that the U.S. served as a counterbalance to the British Empire.[16]

During the winter of 1861–1862, the Imperial Russian Navy sent two fleets to American waters to avoid their getting trapped if a war broke out with Britain and France. Many Americans at the time viewed this as an intervention on behalf of the Union, though historians deny this.[17]

Alexander Nevsky and the other vessels of the Atlantic squadron stayed in American waters for seven months (September 1863 to June 1864).[18]

1865 saw a major project: the building of a Russian-American telegraph line from Seattle, Washington through British Columbia, Russian America (Alaska) and Siberia - an early attempt to link East-West communications. It failed and never operated.[19]

Alaska purchase

After the Crimean War (1853-1856) Russia felt concern that the British would seize Russian America if a war broke out, strengthening the British in the north Pacific. To avoid this and to raise money, Russia offered in 1859 to sell the territory. In 1867 the United States purchased the whole of Russian America (Alaska) in the Alaska Purchase. All the Russian administrators and military left Alaska but some missionaries stayed on because they had converted many natives to the Russian Orthodox faith.[20]

1900–1918

In 1900, Russia and America were part of the Eight-Nation Alliance suppressing the Boxer Rebellion in the Qing Empire. Russia occupied Manchuria at this time, and the US asserted the Open Door Policy to forestall Russian and German territorial demands from leading to a partition of China into colonies.

In World War I the United States declaration of war on Germany (1917) came after the Czar was overthrown in the February Revolution. The American Expeditionary Forces were just starting to see battle when the October Revolution removed Russia from the war. Even before Germany surrendered, the US participated in Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War with the Polar Bear Expedition and the American Expeditionary Force Siberia.

References

- ↑ Frank A. Golder, "Catherine II and the American Revolution," The American Historical Review 21.1 (1915): 92–96.

- ↑ Nikolai Bolkhovitinov, Russia and the American Revolution (Tallahassee: Diplomatic, 1976): 76.

- ↑ Bolkhovitinov, Russia and the American Revolution, 80–84.

- ↑ Golder, "Catherine II and the American Revolution," 92.

- ↑ Norman Saul, Distant Friends: the United States and Russia, 1763–1867 (Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1991): 12.

- ↑ Golder, "Catherine II and the American Revolution," 92.

- ↑ Golder, "Catherine II and the American Revolution," 93.

- ↑ Lawrence Kaplan, The American Revolution and "a Candid World" (Kent: Kent State UP, 1977): 91.

- ↑ Saul, Distant Friends: the United States and Russia, 7.

- ↑ Golder, "Catherine II and the American Revolution," 94.

- ↑ Golder, "Catherine II and the American Revolution," 94.

- ↑ Golder, "Catherine II and the American Revolution," 95.

- ↑ Bolkhovitinov, Russia and the American Revolution, 50–52.

- ↑ Seeger, Murray (2005). Discovering Russia: 200 Years of American Journalism. AuthorHouse. p. 97. ISBN 9781420842593. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

In 1801 [...] President Jefferson initiated relations with the new czar, Alexander I, sending Leverett Harris, a political friend from Pennsylvania, as the first American consul-general to Russia.

- ↑ Kirchner, Walther (1975). Studies in Russian-American Commerce 1820-1860. Leiden (The Netherlands): Brill Archive. p. 191. ISBN 9789004042384. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

[...] in St. Petersburg, Levett Harris [...] had been America's first consul from 1803 to 1816 [...]

- ↑ Norman A. Graebner, "Northern Diplomacy and European Neutrality," Why the North Won the Civil War, ed. David Donald (New York: Collier Macmillan Publishers, 1960), pp. 57-8.

- ↑ Thomas A. Bailey, "The Russian Fleet Myth Re-Examined," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Jun., 1951), pp. 81–90 in JSTOR

- ↑ Davidson, Marshall B. (June 1960). "A ROYAL WELCOME for the RUSSIAN NAVY". American Heritage Magazine 11 (4): 38.

- ↑ Rosemary Neering, Continental Dash: The Russian-American Telegraph (1989)

- ↑ Ronald Jensen, The Alaska Purchase and Russian-American Relations (1975)

See also

- Russia–United States relations

- Soviet Union–United States relations

- United States Ambassador to Russia

| ||||||

.svg.png)