Run for Tunis

| The Run for Tunis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tunisian Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| ||||||

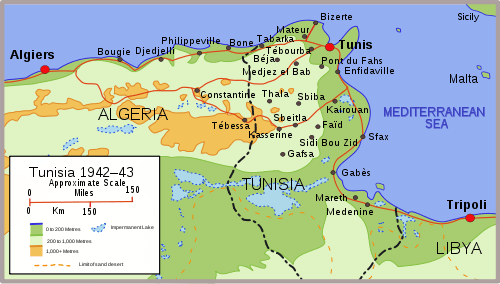

The Run for Tunis was part of the Tunisia Campaign in the Second World War. It took place during November and December 1942. Once French opposition to the Allied Operation Torch landings had ceased in mid-November, the Allies made a rapid advance by a division-sized force east from Algeria in an attempt to capture Tunis and forestall an Axis build up in Tunisia. This they narrowly failed to do. Although elements of the Allied attack got within less than 20 mi (32 km) of Tunis by late November, the defenders were able to reorganise and counter-attack, pushing them back nearly 20 mi (32 km) to positions which had stabilised by the year′s end.

Background

Allies

The planners of Operation 'Torch' had had to assume the worst case regarding the extent of Vichy opposition to landings and the invasion convoys had been assault-loaded with a preponderance of infantry to meet heavy ground opposition. This meant that at Algiers the disembarkation of mobile forces for an advance to Tunisia would necessarily be delayed.[1] Mobile forces, including armour, did not commence disembarkation until 12 November making an advance eastwards possible by 15 November.[2] At this stage, the Allies had available for an attack on Tunisia only two infantry brigade groups from 78th Infantry Division, an armoured regimental group from 6th Armoured Division ("Blade Force") and some additional artillery. Plans were thus a compromise and the Allies realised that an attempt to reach Bizerta and Tunis overland before the Axis could establish themselves represented a gamble which depended on the ability of the navy and air force to delay the Axis build-up.[3] Nevertheless, they believed if they moved quickly, before the newly arrived Axis forces were fully organised, they would still be able to capture Tunisia at relatively little cost.[nb 1]

Axis

The Allies, although they had provided for the possibility of strong Vichy opposition to the Torch landings both in terms of infantry and air force allocations, seriously underestimated the Axis appetite for and speed of intervention in Tunisia.[5] Furthermore, once operations had commenced and despite clear intelligence reports regarding the Axis reaction, the Allies were slow to respond and it was not until nearly two weeks after the landings that air and naval plans were made to interdict Axis sea transport to Tunis.[6] At the end of November naval Force K was reformed in Malta with three cruisers and four destroyers and Force Q formed in Bône with three cruisers and two destroyers. No Axis ships sailing to Tunis were sunk in November but the Allied naval forces had some success in early December sinking seven Axis transports. However, this came too late to affect the fighting on land because the armoured elements of 10th Panzer Division had already arrived. To counter the surface threat Axis convoys were switched to daylight when they could be protected by air cover. Night convoys resumed on completion of the extension of Axis minefields which severely restricted the activities of Force K and Force Q.[7]

Vichy

Tunisian officials were undecided about whom to support, and they did not close access to their airfields to either side. As early as 9 November, it was reported that reconnaissance reported that 40 German aircraft had landed at Tunis, and on 10 November British photographic reconnaissance showed around 100 German aircraft of various types on the airfield.[8] On 10 November, the Italian Air Force sent a flight of 28 fighters to Tunis. Two days later an airlift began that would bring in over 15,000 men and 581 short tons (527 t) of supplies, backed up with transport ships that added 176 tanks, 131 artillery pieces, 1,152 vehicles, and 13,000 short tons (12,000 t) of supplies. By the end of the month they had shipped in three German divisions, including the 10th Panzer Division, and two Italian infantry divisions. On 12 November, Walther Nehring was assigned command of the newly formed XC Corps, and flew in on 17 November.

However, the French commander in Tunisia—General Barré—was untrusting of the Italians and moved his troops into the mountains and formed a defensive line from Tebersouk through Majaz al Bab (also referred to as Medjez el Bab), ordering that anyone attempting to cross the line should be shot.[9]

Prelude

Vichy Armistice

By 10 November, French opposition to the Torch landings had ceased,[10] creating a military vacuum in Tunisia. On 9 November, Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson had taken command of the Eastern Task Force in Algiers which was renamed British 1st Army.[11] He immediately ordered troops eastward to seize the ports of Bougie, Philippeville and Bône and the airfield at Djedjelli preliminary to advancing into Tunisia. Allied planning staff had previously ruled out an assault landing in Tunisia because of a lack of sufficient troops and the threat from the air. As a result, Anderson needed to get his limited force east as quickly as possible before the Axis could build a defensive critical mass in Tunis.[10]

On 11 November, the British 36th Infantry Brigade had landed unopposed at Bougie but logistic difficulties meant Djedjelli was only reached by road on 13 November.[10] Bône airfield was occupied following a parachute drop by 3rd Parachute Battalion and this was followed up on 12 November by No. 6 Commando seizing the port.[12] Advanced guards of 36th Brigade reached Tebarka on 15 November and Djebel Abiod on 18 November where they made first contact with opposition forces.[13]

Further south a U.S. parachute battalion had on 15 November made an unopposed drop on Youks-les-Bains, capturing the airfield there, and advancing to take the airfield at Gafsa on 17 November.[13]

On 19 November, General Nehring demanded passage for his forces across the bridge at Medjez and was refused by Barré. The Germans attacked twice and were repulsed. However, the French took heavy casualties and, lacking armour and artillery, were obliged to withdraw.[9][13]

Despite some Vichy French forces, such as Barré′s units, openly siding against the Axis, the position of Vichy forces generally had remained uncertain. On 22 November, the North African Agreement finally placed Vichy French North Africa on the allied side, allowing the Allied garrison troops to be sent forward to the front. By this time, the Axis had been able to build up an entire Corps, and the Axis forces outnumbered their Allied counterparts in almost all ways.

Plan

There were two roads eastwards into Tunisia from Algeria. The Allied plan was to advance along the two roads and take Bizerte and Tunis. Once Bizerte was taken Torch would come to an end.

Attacking in the north toward Bizerte would be British 36th Infantry Brigade, supported by "Hart Force", a small mobile detachment from British 11th Infantry Brigade,[11] and to the south British 11th Infantry Brigade, supported on their left by "Blade Force", an armoured regimental group commanded by Colonel Richard Hull which included the tanks of 17th/21st Lancers, a U.S. light tank battalion plus motorised infantry, paratroops, artillery, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns and engineers.[14][15] Both infantry brigades were part of British 78th Infantry Division whose commander—Major-General Vyvyan Evelegh—was put in field command of the operation.

Battle

First contact

The two Allied columns advanced towards Djebel Abiod and Beja respectively. The Luftwaffe—happy to have local air superiority while the Allies planes had to fly from relatively distant bases in Algeria—harassed them all the way.[16]

The leading elements of 36th Brigade on the northern road made rapid progress until 17 November, the same day Nehring arrived, when they met a mixed force of 17 tanks and 400 paratroops with self-propelled guns at Djebel Abiod. They succeeded in knocking out 11 tanks, but having no armoured support[17] their advance was halted while the fight at Djebel Abiod continued for nine days.[18]

Allies attack

The two Allied columns concentrated at Djebel Abiod and Beja, preparing for an assault on 24 November. The 36th Brigade was to advance from Djebel Abiod towards Mateur and 11th Brigade was to move down the valley of the River Merjerda to take Majaz al Bab (shown on Allied maps as Medjez el Bab or just Medjez) and then to Tebourba, Djedeida and Tunis. Blade Force was to strike across country on minor roads in the gap between the two infantry brigades towards Sidi Nsir and make flanking attacks on Terbourba and Djedeida.[19]

The northern attack did not take place because torrential rain had slowed the build-up. In the south, 11th Brigade were halted by stiff resistance at Medjez. However, Blade Force passed through Sidi Nsir to reach the Chouigui Pass, north of Terbourba. Then part of Blade Force comprising 17 light M3 light tanks of Company C, 1st Battalion, 1st Armored Regiment, U.S. 1st Armored Division under the command of Major Rudolph Barlow, supported by armoured cars of the Derbyshire Yeomanry, infiltrated behind Axis lines to the newly activated airbase at Djedeida in the afternoon. In a lightning attack, the Allied tanks destroyed more than 20 Axis planes, also shooting up several buildings, supply dumps, and killing and wounding a number of the defenders. However, without infantry support, they were not in a position to consolidate their gains and withdrew to Chouigui.[20]

Blade Force′s attack caught Nehring by surprise and alerted him to the vulnerability of the strong garrison at Medjez being outflanked. He decided to withdraw from Medjez and strengthen Djedeida, only 30 km (19 mi) from Tunis.[21]

The 36th Brigade′s delayed attack went in on 26 November. However, Nehring had used the time bought holding the position at Djebel Abiod to create an ambush position at Jefna on the road between Sedjenane and Mateur. The Germans occupied high ground on either side of the road, which after the recent heavy rains was very muddy and the ground on either side impassable for vehicles. The ambush worked perfectly with the leading battalion taking 149 casualties.[22] 36th Brigade′s commander—Brigadier Kent-Lemon—sent units into the hills to try to flush the German positions out, but the stubborn resistance of the paratroopers combined with the cleverly planned interlocking defences proved too much. A supporting landing by the 1st Commandos 14 mi (23 km) west of Bizerta on 30 November in an attempt to outflank the Jefna position failed in its objective and they had rejoined 36th Brigade by 3 December.[13] The position remained in German hands until the last days of fighting in Tunisia the following spring[23]

German retirement

Early on 26 November, the 11th Brigade were able to enter Medjez unopposed and by late in the day had taken positions in and around Tebourba, which had also been evacuated by the Germans, preparatory to advancing on Djedeida. However, on 27 November the Germans attacked in strength killing 137 men and taking 286 prisoners of war. The 11th Brigade made a new attempt to regain the initiative in the early hours of 28 November, attacking towards Djedeida airfield with the help of armour from U.S. 1st Armored Division′s Combat Command "B", which quickly lost 19 tanks to anti-tank guns positioned within the town.[24]

On 29 November, fresh units from 78th Division′s third brigade—the Guards Brigade, which had arrived at Algiers on 22 November—started to arrive at the front line to relieve 11th Brigade′s battered battalions.[25]

On 29 November, Combat Command "B" of U.S. 1st Armored Division had concentrated forward for an attack in conjunction with Blade Force planned for 2 December. Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion—the Parachute Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel John Dutton Frost—would be dropped on 3 December near enemy airfields around Depienne 30 mi (48 km) south of Tunis (Operation OUDNA) to destroy Stuka dive bombers which had been causing considerable problems and threaten Tunis from the south. As it was, they dropped near a place where an experienced Italian Bersaglieri infantry battalion happened to be.[26] Radio Rome reported that the Bersaglieri captured 300 British Paratroops.[27] However, the British paratroopers claim that they fought against the 5th FJR Afrika (5th Fallschirmjager Regiment Africa) supported by tanks and heavy armoured cars,[28] although some admit that Italians took part in the fighting and captured Lieutenant Denis Boiteux-Buchanan's platoon.[29] Italian Marines reinforced the Germans and clashed with the British paratroopers on 1 December.[30] The British parachutists nevertheless reached Oudna, but the main armoured attack did not take place having been forestalled by an Axis counterattack on 1 December leaving the survivors of the raid to make their way back to home lines, rejoining 78th Infantry Division on 3 December.[31] Lance-Corporal David Murdoch, a direct participant, has been critical of the operation:

It had been badly planned and based on inaccurate information that resulted in us being dropped into an area surrounded by German and Italian forces backed with armoured support. The fact that there were no aircraft at Oudna airfield meant that the operation had been completely unnecessary.[32]

The Axis counterattack—led by Major-General Wolfgang Fischer, whose 10th Panzer Division had just arrived in Tunisia—[33] came from the north toward Tebourba. Blade Force became heavily engaged, suffering considerable casualties. By the evening of 2 December, Blade Force had been withdrawn leaving 11th Brigade and Combat Command "B" to deal with the Axis attack.[31] This threatened to cut off 11th Brigade and break through into the Allied rear but desperate fighting by 2nd battalion The Hampshire Regiment (from the Guards Brigade) and the 1st battalion East Surrey Regiment over four days delayed the Axis advance. This together with the effort of Combat Command "B" in opposing mixed armoured and infantry attacks from the south east permitted a controlled withdrawal to the high ground on each side of the river west of Terbourba.[34] The Hampshire Regiment battalion suffered 75% casualties in the battle during which one of its company commanders—Major H.W. Le Patourel—was awarded the Victoria Cross.[35] The Surreys sustained nearly 60% casualties.[36]

As Allied troops built up in Tunisia, a new H.Q. under 1st Army was activated in early December, that of British V Corps under Lieutenant-General Charles Allfrey, to take over command of all forces in the Tebourba sector, which by this time included 6th Armoured Division, 78th Infantry Division, Combat Command B from US 1st Armored Division, British 1st Parachute Brigade and 1st and 6th Commandos.[37][38] Despite Anderson′s wish to make one more attempt to break through to Tunis, Allfrey considered the weakened units facing Tebourba were highly threatened and ordered a retreat of roughly 6 mi (9.7 km) to the high positions of Longstop Hill (djebel el Ahmera) and Bou Aoukaz on each side of the river. On 10 December, Axis tanks attacked Combat Command "B" on Bou Aoukaz becoming hopelessly bogged down in the mud. In turn, the U.S. tanks counter-attacked and were also mired and picked off, losing 18 tanks.[39] Allfrey was still concerned over the vulnerability of his force and ordered a further withdrawal west so that by the end of 10 December Allied units held a defensive line just east of Medjez el Bab. This string of Allied defeats in December cost them dearly; 173 tanks, 432 other vehicles, and 170 artillery pieces were lost, in addition to thousands of casualties.

Stalemate

The Allies started a buildup for another attack, and were ready by late December 1942. The continued but slow buildup had brought Allied force levels up to a total of 54,000 British, 73,800 American, and 7,000 French troops. A hasty intelligence review showed about 125,000 combat and 70,000 service troops, mostly Italian, in front of them.

On the night of 16/17 December, a company of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division made a successful raid on Maknassy, 155 mi (249 km) south of Tunis, and took 21 German prisoners. The main attack began the afternoon of 22 December, despite rain and insufficient air cover, elements of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division′s 18th Regimental Combat team and 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards of 78th Division′s Guards Infantry Brigade made progress up the lower ridges of the 900 ft (270 m) Longstop Hill that controlled the river corridor from Medjez to Tebourba and thence to Tunis. By the morning of 23 December the Coldstreams had driven back the elements of the 10th Panzer Division on the summit were then relieved by 18 RCT and were withdrawn to Mejdez. The Germans regained the hill in a counter-attack and the Coldstreams were ordered back to Longstop. The next day, they had regained the peak and with 18 RCT dug in. However, by 25 December, with ammunition running low and Axis forces now holding adjacent high ground, the Longstop position became untenable and the Allies were forced to withdraw to Medjez,[40] and by 26 December 1942 the Allies had withdrawn to the line they had set out from two weeks earlier, having suffered 20,743 casualties. The Allied run for Tunis had been stopped.

See also

- North African Campaign timeline

- List of World War II Battles

Footnotes

- Notes

- Citations

- ↑ Hinsley, pp. 472-473

- ↑ Hinsley, p. 497

- ↑ Playfair, p. 239.

- ↑ Hinsley, p. 492

- ↑ Hinsley, p. 487

- ↑ Hinsley, p. 493

- ↑ Hinsley, pp. 495-496

- ↑ Playfair, p. 152.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Watson (2007), p. 60

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Anderson (1946), p. 2 The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779. p. 5450. 5 November 1946. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Playfair, p. 153.

- ↑ Anderson (1946), p. 4 The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779. p. 5452. 5 November 1946. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Anderson (1946), p. 5 The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779. p. 5453. 5 November 1946. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ Ford (1999), p.15

- ↑ Watson (2007), p.61

- ↑ Ford (1999), p. 17

- ↑ Hinsley, pp. 497-498

- ↑ Ford (1999), pp. 19-22

- ↑ Ford (1999), p. 23

- ↑ Ford (1999), pp. 23-25

- ↑ Ford (1999), p.25

- ↑ Ford (1999), p.28

- ↑ Ford (1999), p. 40

- ↑ Ford (1999), p37-38

- ↑ Ford (1999), p. 39

- ↑ Lanza, Colonel Conrad H. "Perimeters in Paragraphs: North Africa" (PDF). The Field Artillery Journal (February, 1943): 146. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ "The Text of the Day's Communiques on Fighting in Various Zones: Italian". New York Times (5 December 1942). Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ Stainforth, Peter; Booth, Eric. "North Africa, November 1942- May 1943". Airborne Engineers Association website. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ "Young recalled how he heard later that after Boiteux-Buchanan's men at Depienne were quickly overwhelmed by Italian troops." British Paratrooper vs Fallschirmjager, David Greentree, p. 59, Osprey Publishing, 2013

- ↑ "On 1 December the MILMART company attached to the 'Grado' Bn was used to reinforce a German detachment, fighting the regiment's first action of the Tunisian campaign against British paratroopers at Pont du Fahs; two of the Blackshirts earned Iron Crosses." Italian Navy and Air Force Elite Units and Special Forces 1940-45, Piero Crociani, p. 36, Osprey Publishing, 2013

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Anderson (1946), p. 6 The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779. p. 5454. 5 November 1946. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ L/Cpl David B Murdoch: Lost In A Dry Land

- ↑ Watson (2007), pp. 62-63

- ↑ Ford (1999), p.50

- ↑ Ford (1999), p. 47

- ↑ Watson (2007), p. 63

- ↑ Playfair, p. 183.

- ↑ Anderson (1946), p. 7 The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779. p. 5455. 5 November 1946. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ Ford (1999), p.51

- ↑ Ford (1999), p.53-54

References

- Anderson, Charles R. Tunisia 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. WWII Campaigns. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-12.

- Anderson, Lt.-General Kenneth (1946). Official despatch by Kenneth Anderson, GOC-in-C First Army covering events in NW Africa, 8 November 1942–13 May 1943 published in The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779. pp. 5449–5464. 5 November 1946. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- Atkinson, Rick (2003). An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942-1943. Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11636-9.

- To Bizerte with the II Corps 23 April to 13 May 1943. American Forces in Action series. United States Army Center of Military History. 1990 [1943]. CMH Pub 100-6.

- Bauer, Eddy; Young, Peter (general editor) (2000) [1979]. The History of World War II (Revised ed.). London, UK: Orbis Publishing. ISBN 1-85605-552-3.

- Blaxland, Gregory (1977). The Plain Cook and the Great Showman. ISBN 0-7183-0185-4.

- Ford, Ken (1999). Battleaxe Division. Stroud (UK): Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-1893-4.

- Gooch, John (Editor); Ceva, Lucio (1990). "The North African Campaign 1940-43: A Reconsideration". Decisive Campaigns of the Second World War. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-3369-0.

- Hinsley, F.H.; Thomas, E.E.; Ransom, C. F. G.; Knight, R. C. (1981). British Intelligence in the Second World War. Its influence on Strategy and Operations. Volume Two. London: HMSO. ISBN 0 11 630934 2.

- Mead, Richard (2007). Churchill's Lions: A biographical guide to the key British generals of World War II. Stroud (UK): Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-431-0.

- Playfair, Major-General I.S.O.; Molony, Brigadier C.J.C.; with Flynn, Captain F.C. (R.N.) & Gleave, Group Captain T.P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO:1966]. Butler, Sir James, ed. The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume IV: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-068-8.

- Watson, Bruce Allen (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942-43. Stackpole Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.