Rudolf Vrba

| Rudolf Vrba | |

|---|---|

|

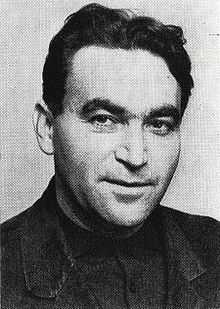

Vrba in 1960 | |

| Born |

Walter Rosenberg 11 September 1924 Topoľčany, Czechoslovakia |

| Died |

27 March 2006 (aged 81) Vancouver, Canada |

| Nationality | Slovakian |

| Other names | "Rudolf Vrba" |

| Ethnicity | Jewish |

| Citizenship | British (1966), Canadian (1972) |

| Education | Dr. Tech. Sc. in chemistry and biology (1951), Prague Technical University |

| Occupation | Associate professor of pharmacology, University of British Columbia |

| Known for | Vrba–Wetzler report |

| Spouse(s) | Gerta Vrbová (m. 1944), Robin Vrba (m. 1975) |

| Children | Dr. Helena Vrbová, Zuza Vrbová Jackson |

| Parent(s) | Elias Rosenberg, Helena Rosenberg (née Grunfeldova) |

| Awards |

Czechoslovak Medal of Bravery (c. 1945) Doctor of Philosophy Honoris Causa, University of Haifa (1998) Order of the White Double Cross, 1st class, Slovakia (2007) |

Rudolf "Rudi" Vrba (11 September 1924 – 27 March 2006) is known for having escaped from the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II, in April 1944 at the height of the Holocaust, and for having provided some of the most detailed information about the mass murder that was taking place there.

Originally from Slovakia, Vrba and a fellow prisoner, Alfréd Wetzler (1918–1988), managed to flee Auschwitz on 10 April 1944, three weeks after German forces invaded Hungary (a German ally) and began deporting the country's Jewish population to Auschwitz.[1] The 40 pages of information the men passed to Jewish officials when they arrived in Slovakia on 24 April, which included the information that arrivals were being gassed and not resettled, became known as the Vrba–Wetzler report.[2] While it confirmed material in earlier reports from Polish and other escapees, Miroslav Kárný writes that it was unique in its "unflinching detail."[3]

There was a delay of several weeks before information from the report was distributed widely enough to gain the attention of governments. Mass transports of Hungary's Jews to Auschwitz began on 15 May 1944 at a rate of 12,000 people a day; most of them were sent straight to the gas chambers. Vrba argued until the end of his life that the deportees would have refused to board the trains had they known they were not being resettled. His position is generally not accepted by Holocaust historians.[4]

Material from the Vrba–Wetzler and earlier reports appeared in newspapers and radio broadcasts in the United States and Europe, particularly in Switzerland, throughout June and into July 1944, prompting world leaders to appeal to Hungarian regent Miklós Horthy to halt the deportations.[5] On 7 July he ordered an end to them, possibly fearing he would be held responsible after the war. By then 437,000 Jews had been deported, constituting almost the entire Jewish population of the Hungarian countryside, but another 200,000 living in Budapest were saved.[6]

Early life and arrest

_high_school_photo-1.jpg)

Vrba was born Walter Rosenberg in Topoľčany, Czechoslovakia, to Elias Rosenberg and his wife, Helena (née Grunfeldová), who owned a steam sawmill in Jaklovce, near Margecany. The name "Rudolf Vrba" was given to him by the Slovak Jewish Council in April 1944 after his escape.[7]

Because he was a Jew, Vrba was excluded at the age of 15 from the local high school under the Slovak version of the Nazis' Nuremberg Laws, and went to work instead as a labourer. There were restrictions on where Jews could live and travel, they were required to wear a yellow badge, and available jobs went first to non-Jews.[8]

In 1942 it was announced that Jews were to be sent to "reservations" in Poland, starting with the young men. Vrba, then aged 17, decided instead to join the Czechoslovak Army in England. He reached the Hungarian border, but the border guards handed him back to the Slovak authorities, who in turn sent him to the Nováky transition camp, a holding camp for Jews awaiting deportation. He managed to escape briefly, but was caught by a policeman who became suspicious when he noticed that Vrba was wearing two pairs of socks.[8]

Auschwitz

Auschwitz I

Vrba was deported to the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland on 15 June 1942, and on 30 June was sent to Auschwitz I, the administrative center for the satellite camps.[9] There he was assigned to work in the Aufräumungskommando, where property taken from new inmates was repackaged.[10] The work involved being present on the Judenrampe, the platform where the trains carrying Jews arrived, to meet the arrivals and sort through their possessions. He also had to enter the trains and remove the bodies of passengers who had died. He worked there from 18 August 1942 until 7 June 1943. He told Claude Lanzmann for the documentary film Shoah (1985) that he had seen around 200 trains arrive during those 10 months.[11]

Though he was housed in Auschwitz I (in Block 4), the storage facilities where he worked (Effektenlager I and II) occupied several dozen barracks in the BIIg sector of Auschwitz II-Birkenau, the extermination camp, two-and-a-half miles (4 km) from the main camp. The barracks were nicknamed Canada I and Canada II by the prisoners, because they contained food, clothing and medicine, and were regarded as the land of plenty.[12] It was thanks to this access that Vrba was able to stay healthy during his time in the camp.[13]

Auschwitz II (Birkenau)

On 15 January 1943 Vrba was sent to be housed in Block 16 of Auschwitz II-Birkenau, the extermination camp, where he continued to work in the "Canada" facility, now tattooed as prisoner no. 44070. He tried to commit to memory the numbers he saw arriving and the place of origin of each transport. Many had brought clothes for different seasons and utensils, he wrote, which suggested that they believed the stories about resettlement.[14] This strengthened his conviction that he had to escape; he believed the transports ran smoothly only because there was no knowledge of what lay ahead.[15]

In June 1943 he was given the job of registrar in the quarantine section at Birkenau sector B II, which allowed him to speak to the deportees who had been selected as slave labour.[16] From the office he used inside his barracks, he could see the lorries driving towards the gas chambers, and estimated that 10 percent of each transport was selected to work and the rest to be killed.[14] By April 1944 he calculated that 1,750,000 Jews had been killed, a figure higher than that accepted by historians, but which decades later he insisted was accurate.[17]

Conversations about Hungarian Jews

Vrba wrote in his memoir that, on 15 January 1944, a Polish kapo told him that a million Hungarian Jews would be arriving soon, and that a new railway line was being built that would go straight to the crematoria. Vrba said he also overheard SS guards discuss how they would soon have Hungarian salami by the ton. "When a series of transports of Jews from the Netherlands arrived, cheeses enriched the war-time rations," he wrote. "It was sardines when ... French Jews arrived, it was halva and olives when transports of Jews from Greece reached the camp, and now the SS were talking of 'Hungarian salami,' a well-known Hungarian provision suitable for taking along on a long journey."[18]

Although Vrba is clear in his autobiography that he took overheard these conversations, and that warning the Hungarian community was one of the motives for his escape, there is no mention of the Hungarian Jews in the Vrba–Wetzler report.[19] The discrepancy has led several historians, including Miroslav Kárný and Randolph L. Braham, to dispute Vrba's later recollections, though not the Vrba–Wetzler report itself.[20]

Escape

When he arrived in Birkenau, Vrba discovered that Alfréd Wetzler, someone he knew from Trnava, was working in the mortuary, registered as prisoner no. 29162. The men decided to escape together.[21] On 7 April 1944, with the help of two other prisoners, they hid in a pile of wood between the inner and outer perimeter fences, sprinkling the area with tobacco soaked in gasoline to fool the guards' dogs.[22] According to Kárný, at 20:33 that evening, SS-Sturmbannführer Fritz Hartjenstein, the Birkenau commander, was informed by teleprinter that two Jews had escaped.[23]

The men knew from previous escape attempts by others that, once their absence was noted during the evening appell (roll call), the guards would continue the search for three days. They therefore remained in hiding, in silence, for three nights and throughout the fourth day. Wetzler wrote in his memoir that they tied strips of flannel across their mouths and tightened them whenever they felt a tickle in their throats.[24] At 9 pm on 10 April, they crawled out of their hiding place and headed south toward Slovakia 80 miles (130 km) away, walking parallel to the Soła river.[25]

Vrba–Wetzler report

Writing the report

The men crossed the Polish-Slovakian border on 21 April. They went to see a local doctor in Čadca, Dr. Pollack, someone Vrba knew from his time in the first transit camp. Pollack had a contact in the Slovak Judenrat (Jewish Council), which was operating an underground group known as the "Working Group," and arranged for them to send people from their headquarters in Bratislava to meet the men. Pollack was distressed to learn the probable fate of his parents and siblings, who had been deported in 1942.[27]

Vrba and Wetzler spent the night in Čadca in the home of a relative of the rabbi Leo Baeck, and the next day, 24 April 1944, met the chairman of the Jewish Council, Dr. Oscar Neumann, a German-speaking lawyer. Neumann placed the men in different rooms in a former old people's home and interviewed them separately over three days. Vrba writes that he began by drawing the inner layout of Auschwitz I and II, and the position of the ramp in relation to the two camps. He described the internal organization of the camps, how Jews were being used as slave labour for Krupp, Siemens, IG Farben and D.A.W., and the mass murder in gas chambers of those who had been chosen for Sonderbehandlung, or "special treatment."[28]

The report was written and re-written several times. Wetzler wrote the first part, Vrba the third, and the two wrote the second part together. They then worked on the whole thing together, re-writing it six times.[29] Neumann's aide, Oscar Krasniansky, an engineer and stenographer who later took the name Oskar Isaiah Karmiel, translated it from Slovak into German with the help of Gisela Steiner.[29] They produced a 40-page report in German, which was completed by Thursday, 27 April 1944. Vrba wrote that the report was also translated into Hungarian.[30] The original Slovak version of the report was not preserved.[29]

Contents

The report contained a detailed description of the geography and management of the camps, and of how the prisoners lived and died. It listed the transports that had arrived at Auschwitz since 1942, their place of origin, and the numbers "selected" for work or the gas chambers.[31] Kárný writes that the report is an invaluable historical document because it provides details that were known only to prisoners, most of whom died, including, for example, that discharge forms were filled out for prisoners who were gassed, indicating that death rates in the camp were actively falsified.[32]

It also contained sketches and information about the layout of the gas chambers. In a sworn deposition for the trial of SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann in 1961, and in his book I Cannot Forgive (1964), Vrba said that he and Wetzler obtained the information about the gas chambers and crematoria from Sonderkommando Filip Müller and his colleagues, who worked there. Müller confirmed Vrba's story in his Eyewitness Auschwitz (1979).[33] Auschwitz scholar Robert Jan van Pelt wrote in 2002 that the description contains errors, but that "given the conditions under which information was obtained, the lack of architectural training of Vrba and Wetzlar [sic], and the situation in which the report was compiled, one would become suspicious if it did not contain errors. ... Given the circumstances, the composite 'crematorium' reconstructed by two escapees without any architectural training is as good as one could expect."[34] The report offered the following description:

.jpg)

At present there are four crematoria in operation at BIRKENAU, two large ones, I and II, and two smaller ones, III and IV. Those of type I and II consist of 3 parts, i.e.,: (A) the furnace room; (B) the large halls; and (C) the gas chamber. A huge chimney rises from the furnace room around which are grouped nine furnaces, each having four openings. Each opening can take three normal corpses at once and after an hour and a half the bodies are completely burned. This corresponds to a daily capacity of about 2,000 bodies. Next to this is a large "reception hall" which is arranged so as to give the impression of the antechamber of a bathing establishment. It holds 2,000 people and apparently there is a similar waiting room of the floor below. From there a door and a few steps lead down into the very long and narrow gas chamber. The walls of this chamber are also camouflaged with simulated entries to shower rooms in order to mislead the victims. This roof is fitted with three traps which can be hermetically closed from the outside. A track leads from the gas chamber to the furnace room.

The gassing takes place as follows: the unfortunate victims are brought into hall (B) where they are told to undress. To complete the fiction that they are going to bathe, each person receives a towel and a small piece of soap issued by two men clad in white coats. They are then crowded into the gas chamber (C) in such numbers there is, of course, only standing room. To compress this crowd into the narrow space, shots are often fired to induce those already at the far end to huddle still closer together.

When everybody is inside, the heavy doors are closed. Then there is a short pause, presumably to allow the room temperature to rise to a certain level, after which SS men with gas masks climb on the roof, open the traps, and shake down a preparation in powder form out of tin cans labeled "CYKLON" "For use against vermin," which is manufactured by a Hamburg concern. It is presumed that this is a "CYANIDE" mixture of some sort which turns into gas at a certain temperature. After three minutes everyone in the chamber is dead. No one is known to have survived this ordeal, although it was not uncommon to discover signs of life after the primitive measures employed in the Birch Wood. The chamber is then opened, aired, and the "special squad" carts the bodies on flat trucks to the furnace rooms where the burning takes place. Crematoria III and IV work on nearly the same principle, but their capacity is only half as large. Thus the total capacity of the four cremating and gassing plants at BIRKENAU amounts to about 6,000 daily.[35]

How the report was distributed

The dates on which the report was passed to certain individuals has become a matter of importance within Holocaust historiography. This is partly because there is a question as to what the Hungarian government knew about the gas chambers in Auschwitz before it facilitated the mass deportations, which began on 15 May 1944, and partly because Vrba alleged that lives were lost because the report was not distributed quickly enough by Jewish leaders, particularly Rudolf Kastner of the Budapest Aid and Rescue Committee.[36]

Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer writes that Oscar Krasniansky of the Jewish Council, who translated the report into German from Slovak as Vrba and Wetzler were writing and dictating it, made conflicting statements about the report after the war. In the first statement, he said he had handed the report to Kastner on 26 April 1944 during the latter's visit to Bratislava, but Bauer writes that the report was not finished until 27 April. In another statement, he said he had given it to Kastner on 28 April in Bratislava, but Hansi Brand, Kastner's lover and the wife of Joel Brand, said that Kastner was not in Bratislava until August. Bauer writes that it is nevertheless clear from Kastner's post-war statements that he had early access to the report, though perhaps not in April as Krasniansky claimed.[37] Randolph L. Braham writes that Kastner had a copy by 3 May when he paid a visit to Kolozsvar (Cluj), his home town.[38]

Kastner's reasons for not making the document public are unknown, but Vrba believed until the end of his life that Kastner withheld it in order not to jeopardize negotiations between the Aid and Rescue Committee and Adolf Eichmann, the SS officer in charge of the transport of Jews out of Hungary (see Joel Brand).[39]

Deportations to Auschwitz continue

On 6 June 1944, the day of the Normandy landings, Arnost Rosin (prisoner no. 29858) and Czesław Mordowicz (prisoner no. 84216) arrived in Slovakia, having escaped from Auschwitz on 27 May. Hearing about the Battle of Normandy and believing the war was over, they got drunk to celebrate, using dollars they had smuggled out of Auschwitz. They were promptly arrested for violating the currency laws, and spent eight days in prison before the Jewish Council paid their fines. Rosin and Mordowicz already knew Vrba and Wetzler; Vrba wrote that anyone surviving more than a year in Auschwitz was regarded as a senior member of the "old hands Mafia," and all were known to each other.[41]

On 15 June the men were interviewed by Oscar Krasniansky, the engineer who had translated the Vrba–Wetzler report into German. They told Krasniansky that, between 15 and 27 May 1944, 100,000 Hungarian Jews had arrived at Birkenau and that most were killed on arrival, apparently with no knowledge of what was about to happen to them. Vrba concluded that the report had been suppressed.[40]

Deportations halted

Braham writes that the report was taken to Switzerland by Florian Manoliu of the Romanian Legation in Bern and given to George Mantello, a Jewish businessman from Transylvania who was working as the first secretary of the El Salvador consulate in Geneva. It was thanks to Mantello that the report received, in the Swiss press, its first wide coverage.[42] According to David Kranzler, Mantello asked for the help of the Swiss-Hungarian Students' League to make 50 mimeographed copies of the Vrba–Wetzler and two shorter Auschwitz reports (jointly known as the Auschwitz Protocols, which by 23 June 1944 he had distributed to the Swiss government and Jewish groups. The students made thousands of other copies, which were passed to other students and MPs.[43]

On 19 June Richard Lichtheim of the Jewish Agency in Geneva, who had received a copy of the report from Mantello, wrote to the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem to say that they knew "what has happened and where it has happened," and reported the Vrba–Wetzler figure that 90 per cent of Jews arriving at Birkenau were being killed.[44] Vrba and Oscar Krasniasnky met Vatican Swiss legate Monsignor Mario Martilotti at the Svaty Jur monastery in Bratislava on 20 June. Martilotti had seen the report and questioned Vrba about it for six hours.[45]

As a result of the coverage in the Swiss press, details began to appear elsewhere, including the New York Times and BBC World Service. Daniel Brigham, the New York Times correspondent in Geneva, published a story on 3 July 1944, "Inquiry Confirms Nazi Death Camps," and on 6 July a second, "Two Death Camps Places of Horror; German Establishments for Mass Killings of Jews Described by Swiss."[46] Braham writes that several appeals were made to Horthy, including by the Swiss government, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Gustaf V of Sweden and, on 25 June, Pope Pius XII, possibly after Martilotti passed on the report.[47] On 26 June Richard Lichtheim of the Jewish Agency in Geneva sent a telegram to England calling on the Allies to hold members of the Hungarian government personally responsible for the killings. The cable was intercepted by the Hungarian government and shown to Prime Minister Döme Sztójay, who passed it to Horthy. Horthy ordered an end to the deportations on 7 July and they stopped two days later.[48]

That the Germans were using gas chambers was confirmed on 23 July, when the Majdanek concentration camp near Lublin, Poland, was captured by Soviet soldiers, with its gas chambers intact and 820,000 shoes. Auschwitz itself was liberated by the 28th and 106th corps of the 1st Ukrainian Front of the Red Army on 27 January 1945. Van Pelt writes that the SS learned the lesson of Majdanek and tried to destroy some of the evidence, but the Red Army nevertheless found what was left of four crematoria, as well as 5,525 pairs of women's shoes and 38,000 pairs of men's, 348,820 men's suits, 836,225 items of women's clothing, large numbers of toothbrushes, glasses and dentures, and seven tons of hair.[49]

Vrba's allegations

"Blood for goods" proposals

The timing of the report's distribution remains a source of controversy. For reasons that remain unclear it was not distributed widely until several weeks after Vrba's escape in April.[45] Between 15 May and 7 July 1944, 437,000 Hungarian Jews (12,000 a day) were sent by train to Auschwitz. Vrba believed they would have run or fought had they known they were being sent to their deaths.[50]

He alleged that the report had been withheld deliberately by Rudolf Kastner and the Jewish-Hungarian Aid and Rescue Committee in Budapest in order not to jeopardize complex, and ultimately futile, negotiations with Adolf Eichmann, who had suggested to the committee that they arrange an exchange of up to one million Jews for money and trucks from the US or UK, the so-called "blood for goods" proposal. Vrba wrote in his memoirs that the Jewish communities in Slovakia and Hungary had placed their trust either in the secular Zionist leaders such as the Kastner, or in Orthodox Jewish leaders. The Nazis were aware of this, Vrba wrote, which is why they lured precisely those members of the community into negotiations, supposedly designed to lead to the release of Jews. He maintained that the Nazis in fact intended only to placate the Jewish leadership to avoid the spread of panic, because panic would have slowed down the transports.[39]

Kastner train

The Aid and Rescue Committee's first meeting with Eichmann about the proposal was on 25 April 1944. On 28 April the first trainload of Hungarian Jews left for Auschwitz, although not as part of the mass transports, and around the same time Kastner is believed to have received a copy of the Vrba–Wetzler report, though possibly in German and not yet translated.[51]

Vrba alleged that Kastner failed to distribute the report in order not to jeopardize the Eichmann deal, but acted on it privately by arranging for a trainload of 1,684 Hungarian Jews to escape to Switzerland on the Kastner train, which left Budapest on 30 June. According to John Conway, the escaping party consisted of "themselves, their relatives, a coterie of Zionists, some distinguished Jewish intellectuals, and a number of wealthy Jewish entrepreneurs."[52] Other scholars dispute this emphasis. Ladislaus Löb writes that the party also included over 200 children under 14, many of them orphans, and hundreds of ordinary people such as teachers and nurses.[53] Yehuda Bauer argues that Kastner put his own family on the train to show the other passengers that it was safe, and that in any event he could hardly be expected to exclude his family from it.[54]

The allegations against Kastner became part of a libel case in Jerusalem in 1954, after Malchiel Gruenwald, an Israeli hotelier, accused him in a self-published pamphlet of being a Nazi collaborator. Because Kastner was by then a senior Israeli civil servant, the Israeli government sued Gruenwald. Although Kastner was later exonerated by the Supreme Court, the lower court ruled against the government, and Kastner was assassinated in March 1957 as a result of the ensuing publicity.[55]

Response

Bauer writes that, by the time the Vrba–Wetzler report was prepared, it was already too late for anything to alter the Nazis' deportation plans.[56] He cautions about the need to distinguish between the receipt of information and its "internalization" – the point at which information is deemed worthy of action – arguing that this is a complicated process: "During the Holocaust, countless individuals received information and rejected it, suppressed it, or rationalized about it, were thrown into despair without any possibility of acting on it, or seemingly internalized it and then behaved as though it had never reached them."[57] Bauer argues that Vrba's "wild attacks on Kastner and on the Slovak underground are ahistorical and simply wrong from the start ..."[58] Vrba, in response, alleged that Bauer was one of the Israeli historians who had downplayed Vrba's role in Holocaust historiography in order to defend the Israeli establishment.[52]

After the report

Resistance activities

After he handed his information to the Slovakian Jewish Council in April 1944, Vrba said Krasniansky had assured him that the report was in the right hands. Vrba and Wetzler spent the next six weeks in Liptovský Mikuláš, and continued to make and distribute copies of their report whenever they could. The Slovak Judenrat gave Vrba papers in the name of Rudolf Vrba, showing that he was a "pure Aryan" going back three generations, and supported him financially to the tune of 200 Slovak crowns a week, equivalent to an average worker's salary, and as Vrba wrote, "sufficient to sustain me in an illegal life in Bratislava." On 29 August 1944 the Slovak Army rose up against the Nazis and the reestablishment of Czechoslovakia was announced. Vrba joined the Czechoslovak partisan units in September 1944, and was later awarded the Czechoslovak Medal of Bravery.[59]

After the war

Vrba moved to Prague in 1945, attending and working at the Prague Technical University, where in 1951 he received his doctorate in chemistry and biochemistry (Dr. Tech. Sc.) for a thesis entitled "On the metabolism of butyric acid." This was followed by post-doctoral research at the Czechoslovak Academy of Science, where he received his C.Sc. in 1956. In the summer of 1944 he met a childhood friend Gerta; they married (she took the surname Vrbová, the female version of Vrba) and had two daughters, though the marriage failed shortly thereafter.[60]

In 1958 Vrba received an invitation to an international conference in Israel, and while there he defected.[13] He worked for the next two years at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot.[61] He said later that he could not continue to live in Israel because the same men who had, in his view, betrayed the Jewish community in Hungary were now in positions of power there.[13] He decided in 1960 to move instead to England, becoming a British citizen in 1966. In England he worked for two years in the Neuropsychiatric Research Unit in Carshalton, Surrey, and seven years for the British Medical Research Council.[62]

On 11 May 1960 Eichmann was captured by the Mossad in Buenos Aires and taken to Jerusalem to stand trial. Vrba wrote in his memoir that British newspapers were suddenly full of stories about Auschwitz. He contacted Alan Bestic of the Daily Herald, and his story was published in five installments over one week in March 1961, on the eve of Eichmann's trial.[63] Vrba also submitted a statement in evidence against Eichmann to the Israeli Embassy in London.[64] With Bestic's help, Vrba wrote up the rest of his story for his memoir, I Cannot Forgive (1964), republished as Escape from Auschwitz (1964) and I Escaped from Auschwitz (2002). He also appeared as a witness at one of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials in 1964.[63]

Move to Canada, Zündel trial

Vrba moved to Canada in 1967, working for the Medical Research Council of Canada from 1967 to 1973, and becoming a Canadian citizen in 1972. He spent 1973–1975 as a research fellow at Harvard Medical School, focusing on cancer research, where he met his second wife, Robin. They returned to Vancouver, where she became a real estate agent, and he an associate professor of pharmacology at the University of British Columbia until the early 1990s, specializing in neurology. He became known internationally for over 50 research papers on the chemistry of the brain, and for his work on diabetes and cancer.[65]

Vrba testified in January 1985 at the seven-week trial in Toronto of Holocaust denier Ernst Zündel, who was charged with knowingly publishing false material likely to cause harm to racial or social tolerance. Zündel's lawyer, Doug Christie, accused Vrba of lying about his experiences in Auschwitz, and asked whether he had actually seen anyone being gassed. Vrba replied that he had watched people being taken into the buildings and had seen SS officers throw in gas canisters after them. "Therefore, I concluded it was not a kitchen or a bakery, but it was a gas chamber," Vrba told the court. "It is possible they are still there or that there is a tunnel and they are now in China. Otherwise, they were gassed."[66] Vrba acknowledged that some of the passages in his book, I Cannot Forgive (1964), were based on secondhand accounts.[67]

Vrba died of cancer on 27 March 2006 in Vancouver. He was survived by his first wife Gerta, his second wife Robin, his daughter Zuza Vrbová Jackso and his grandchildren Hannah and Jan. He was pre-deceased by his elder daughter, Dr. Helena Vrbová. His fellow escapee, Alfréd Wetzler, who wrote about Auschwitz using the pen name Jozef Lánik, died in Bratislava, Slovakia, on 8 February 1988.[68]

Reception

Documentaries, books, and awards

Several documentaries have told Vrba's story, including Genocide (1973), directed by Michael Darlow for ITV in the UK; Auschwitz and the Allies (1982), directed by Rex Bloomstein and Martin Gilbert for the BBC; and Shoah (1985), directed by Claude Lanzmann. He was also featured in Witness to Auschwitz (1990), directed by Robin Taylor for the CBC in Canada; Auschwitz: The Great Escape (2007) for the UK's Channel Five; and Escape From Auschwitz (2008) for PBS in the United States.

Vrba featured in an essay by George Klein, the Hungarian-Swedish biologist, "The Ultimate Fear of the Traveller Returning from Hell," in Klein's Pieta (1992), and is the focus of Ruth Linn's Escaping Auschwitz (2004). An academic conference was held in New York in April 2011 to discuss the impact of the Vrba–Wetzler and other Auschwitz reports, resulting in a book, The Auschwitz Reports and the Holocaust in Hungary (2011), edited by Randolph L. Braham and William vanden Heuvel, and published by Columbia University Press. After Vrba's death, his wife made a gift of his papers to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in New York.[69]

British historian Martin Gilbert supported a campaign in 1992 to have Vrba awarded the Order of Canada, and solicited letters from well-known Canadians on his behalf, but was unsuccessful. In 1998, at the instigation of Linn, he received the title of Doctor of Philosophy Honoris Causa from the University of Haifa.[52] He was awarded the Order of the White Double Cross, 1st class, by the Slovakian government in 2007.[70] The Czech One World festival annually presents the "Rudolf Vrba Award" for original documentaries that draw attention to an unknown theme about human rights; the award was established in his name by Mary Robinson, then United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, and Václav Havel, then President of the Czech Republic.[71]

Discrepancies

Several historians have argued that Vrba embellished his later accounts, though not the Vrba–Wetzler report itself. He wrote in his memoir in 1963 that he had overheard SS officers in Auschwitz discuss how a new area was being constructed and that they would soon have "Hungarian salami ... by the ton," allegedly a reference to the imminent arrival of Hungarian Jews, but he did not mention this in his report in April 1944.[19] Although Vrba maintained that warning the Hungarian community was one of the motives for his escape, the report said: "Work is now proceeding on a still larger compound which is to be added later on to the already existing camp. The purpose of this extensive planning is not known to us." It also stated: "When we left on April 7, 1944 we heard that large convoys of Greek Jews were expected."[72] Miroslav Kárný writes:

It is generally accepted that at the time Vrba and Wetzler were preparing their escape, it was known in Auschwitz that annihilation mechanisms were being perfected in order to kill hundreds of thousands of Hungary's Jews. It was this knowledge, according to Vrba, that became the main motive for their escape. ... But in fact, there is no mention in the Vrba and Wetzler report that preparations were under way for the annihilation of Hungary's Jews. ... If Vrba and Wetzler considered it necessary to record rumors about the expected arrival of Greece's Jewish transports, then why wouldn't they have recorded a rumor – had they known it – about the expected transports of hundreds of thousands of Hungary's Jews?[73]

Kárný argues that, long after the war was over, Vrba wanted to testify about the deportations out of a sense of longing, to force the world to face the magnitude of the Nazis' crimes. The suspicion is that this led to a degree of embellishment in later accounts.[73] In a later edition of his memoirs, Vrba responded that he is certain the reference to the imminent Hungarian deportations was in the original Slovakian version of the Vrba–Wetzler report, some of which he wrote by hand, but which did not survive. He wrote that he recalled Oscar Krasniansky of the Slovakian Jewish Council, who translated the report into German, arguing that only actual deaths should be recorded, and not speculation, to lend the report maximum credibility. Vrba speculated that this was the reason Krasniansky omitted the references to Hungary from the German translation, which was the version that was copied around the world.[74]

Survivor versus expert discourse

Vrba was criticized in 2001 in a collection of articles in Hebrew, Leadership under Duress: The Working Group in Slovakia, 1942–1944, by a group of leading Israeli historians with ties to the Slovak community, including Yehuda Bauer, Hanna Yablonka, Gila Fatran and Livia Rothkirchen. The introduction by Giora Amir describes as "a bunch of mockers, pseudo-historians and historians" those who, like Vrba, argue that the Slovakian Jewish Council may have collaborated with the Nazis by concealing what was happening in Auschwitz. Amir writes that the "baseless" accusation was lent credence "when the University of Haifa awarded an honorary doctorate to the head of these mockers, Peter [sic] Vrba."[76] Amir continues:

The heroism of this person, who together with the late Alfréd Wetzler, was among the first to escape from Auschwitz, is beyond doubt. But the fact that, just because he was an Auschwitz prisoner endowed with personal heroism, he has crowned himself as knowledgeable to judge all those involved in the noble work of rescue, and accuse them falsely, deeply disturbs us, the Czech community.[76]

The criticism of Vrba stems from the tension between what Ruth Linn calls survivor and expert discourse. Bauer referred to Vrba's memoir as "not a memoir in the usual sense," alleging that it "contains excerpts of conversations of which there is no chance that they are accurate and it has elements of a second-hand story that does not necessarily correspond with reality." When writing about himself and his personal experiences, Vrba's account is an important and true one, Bauer wrote, but he also argued that Vrba was not justified in seeing himself as an expert on the history of the Holocaust.[77] Vrba often dismissed the opinion of Holocaust historians; regarding the numbers killed at Auschwitz, he said that Bauer and historian Raul Hilberg did not know enough about the history of Auschwitz.[78]

Linn argued in 2004 that certain Israeli historians had misrepresented Vrba's story.[79] Vrba believed they had sought to erase his story from Holocaust historiography because of his views about Kastner and the Hungarian Judenrat, some of whom went on to hold prominent positions in Israel.[52] Linn wrote that Vrba's and Wetzler's names are omitted or their contribution minimized in Hebrew textbooks: standard histories refer to the escape by "two young Slovak Jews," "two chaps," or "two young people," and represent Vrba and Wetzler as emissaries of the Polish underground in Auschwitz. Vrba's book was not translated into Hebrew until 1999, 35 years after its publication in English. Yad Vashem holds one of the world's most extensive collections of Holocaust documentation, but as of 2004 there was no English or Hebrew version there of the Vrba–Wetzler report, an issue the museum attributed to lack of funding. There was a Hungarian translation, but it did not note the names of its authors and, Linn wrote, could be found only in a file that dealt with Rudolf Kastner.[80]

In 2005 Uri Dromi of the Israel Democracy Institute responded that there were at least four popular Israeli books on the Holocaust that mention Vrba, and that Wetzler's testimony was recounted at length in Livia Rothkirchen's Hurban yahadut Slovakia (The Destruction of Slovakian Jewry), published by Yad Vashem in 1961. In rely to Dromi's article, Linn wrote that most books mentioning Vrba were published after 1998, and that earlier mentions were all in obscure texts. Robert Rozett, head librarian at Yad Vashem and author of the entry on the "Auschwitz Report" in Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, said of the Vrba controversy in 2005: "There are people who come into the subject from a certain angle and think that they've uncovered the truth. A historian who deals seriously with the subject understands that the truth is complex and multifaceted."[81]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ The men began their escape on 7 April 1944, hid between an internal and external perimeter fence for three days, and exited the camp on 10 April.

- ↑ Kárný (1998), p. 553ff. For the report, "The Vrba–Wetzler Report", Holocaust Education and Archive Research Team. Sources vary as to how long the report was, depending on which language version they refer to. Some refer to 30 pages and others to 60 (Szabó (2011), pp. 97–99). The typed version produced by the Slovakian Jewish Council in April 1944 was 40 pages long.

- ↑ Karny (1998), p. 554. Several prisoners had escaped before Vrba and Wetzler. Dionisys Lenard from Slovakia escaped in the summer of 1942. A report entitled "Auschwitz—Camp of Death" was published in December 1942 by Natalia Zarembina, a Polish prisoner who escaped. Three or four other prisoners, including Kazimierz Piechowski, another Pole, escaped on 20 June 1942 and reported what was happening inside the camp, and Kazimirez Halori, again from Poland, escaped on 2 November 1942 (Szabó (2011), p. 87).

A two-part report was prepared by the Polish underground in 1943, based on information from Witold Pilecki, a Polish soldier who volunteered to enter Auschwitz to gather intelligence and organize a resistance movement, and who escaped in April 1943. The report included details about the gas chambers, "selection," and the sterilization experiments. It stated that there were three crematoria in Birkenau able to burn 10,000 people daily, and that 30,000 people had been gassed in one day. The report was sent to the Office of Strategic Services in London. Raul Hilberg wrote that it was filed away with a note that there was no indication as to the reliability of the source (Hilberg (2003), p. 1212).

- ↑ For example, see Braham (2011), pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Lipstadt (1993), pp. 233–237; Kárný (1998), p. 558.

- ↑ Bauer (1997), p. 194, for 437,000 deported from the provinces; Bauer (1994), p. 156, for 437,000 deported to Auschwitz between 14 May and 7 July, according to German figures.

- Braham (2011), p. 45, for the countryside being emptied of Jews by July 1944; Bauer (1994), p. 233, for "probably close to 200,000" Jews remaining in Budapest, though see p. 156 for "[w]hat was left were the 250,000 Budapest Jews."

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 404; The Daily Telegraph (12 April 2006).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Vrba (2002), pp. 15–17, 23–28, 38.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 376.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), pp. 87–97, 376–377.

- ↑ Van Pelt (2011), pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 377, footnote 11.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 The Daily Telegraph (12 April 2006)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Martin (1990), p. 194; Linn (2004), pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 389ff; van Pelt (2011), p. 144.

- ↑ Martin (1990), p. 94.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 379, footnote 12. In March 1990 he said: "Hilberg's estimate of 1 million killed [in Auschwitz] is a gross error bordering on ignorance ... According to my observations there were 1,765,000 victims which I counted"; see Nueman (1990).

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 387.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gilbert (1994), p. 551.

- ↑ Kárný (1998), p. 560; Braham (2011), pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 391.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 391; Gilbert (1990), p. 196. That they were helped by two other prisoners, see Wetzler (2007), p. 108. In his book, first published in 1963, Wetzler is "Karol" and Vrba is "Val."

- ↑ Kárný (1998), p. 553.

- ↑ Wetzler (2007), p. 124.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), pp. 392–394.

- ↑ Vrba (1998), p. 62.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), pp. 396–398.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), pp. 399–400.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 This description of how the report was written was recorded in the first post-war Slovak edition, Oswiecim, hrobka štyroch miliónov ľudí ("Auschwitz, the tomb of four million"), Bratislava, 1946, p. 74. Wetzler confirmed it in a letter to Miroslav Kárný dated 14 April 1982; see Kárný (1998), p. 564, footnote 5.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), pp. 402–403.

- ↑ Karny (1998), p. 554; van Pelt (2011), p. 123.

- ↑ Kárný (1998), p. 555.

- ↑ van Pelt (2002), p. 149.

- ↑ van Pelt (2002), p. 151.

- ↑ Świebocki (1997), pp. 218, 220, 224. Świebocki presents this material without paragraph breaks. For ease of reading, two paragraph breaks have been inserted into the text above. Also see "The Vrba–Wetzler Report", part 2.

- ↑ For Vrba's allegations, see Braham (2000), p. 276, footnote 50.

- ↑ Bauer (2002), p. 231.

- ↑ Braham (2000), p. 95.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Vrba (2002), pp. 419–420.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Conway (1997).

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 406.

- ↑ Braham (2000) pp. 95, 214.

- ↑ Kranzler (2000), pp. 98–99.

- ↑ van Pelt (2002), p. 152. That Lichtheim received the report from Mantello, see Kranzler (2000), p. 104. Kranzler places the cable to Jerusalem on 26 June 1944, and writes that Lichtheim referred in the cable to 12,000 Jews being deported daily from Budapest.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Kárný (1998), pp. 556–557.

- ↑ van Pelt (2002), pp. 153–154; Brigham (New York Times) (6 July 1944).

- ↑ Braham (2000), pp. 95, 214; Bauer (2002), p. 230.

- ↑ Rees (2006), pp. 242–243.

- ↑ van Pelt (2002), pp. 154, 158–159.

- ↑ Linn (2011), p. 162.

- ↑ Bauer (1994), p. 156.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Conway (2005).

- ↑ Löb (2009), pp. 115–117.

- ↑ Bauer (1994), p. 198.

- ↑ Bauer (1994), pp. 154, 159, 199.

- ↑ Bauer (1997), pp. 297–307.

- ↑ Bauer (1994), p. 72.

- ↑ Yehuda Bauer in a letter to Ruth Linn, cited in Linn (2004), p. 111.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), pp. 404, 410–411; The Daily Telegraph (12 April, 2006).

- ↑ Martin (8 April 2006)].

- ↑ Barkat (2006.)

- ↑ Sanderson and Smith (Times) (1 April 2006).

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Vrba (2002), pp. ix–xvi.

- ↑ Linn (2004), p. 13.

- ↑ Martin, New York Times (7 April 2006).

- ↑ The Montreal Gazette (25 January 1985).

- ↑ Chapman, Toronto Sun (24 January 1985).

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph (12 April 2006); Martin, New York Times (7 April 2006); Sanderson and Smith, Times (1 April 2006)

- ↑ "International Conference on the Auschwitz Reports", Rosenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and the Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, April 2011.

- ↑ State honours, 1st Class in 2007; see "Holders of the Order of the 1st Class White Double Cross."

- ↑ Sanderson and Smith, Times (1 April 2006); "Rudolf Vrba", One World 2006.

- ↑ Braham (2011), p. 47.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Kárný (1998), p. 559.

- ↑ Vrba (2002), p. 413.

- ↑ Bauer (1994), p. 70; Linn (2004), p. 110–113.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Yehuda Bauer et al (2001), Leadership in Time of Distress: The Working Group in Slovakia, 1942–1944, Kibbutz Dalia: Maarecht, pp. 11–12, cited in Linn (2004), pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Yehuda Bauer in a letter to Ben Ami, translator of Vrba's memoir, cited in Linn (2004), p. 111.

- ↑ Nueman (1990).

- ↑ Linn (2004), p. 55.

- ↑ Linn (2004), pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Dromi (2005).

Sources

- Bauer, Yehuda (1994). Jews for Sale? Nazi–Jewish Negotiations 1933–1945, Yale University Press.

- Bauer, Yehuda (1997). "The Holocaust in Hungary: Was Rescue Possible?" in David Cesarani (ed.), Genocide and Rescue: The Holocaust in Hungary 1944, Berg.

- Bauer, Yehuda (2002). Rethinking the Holocaust, Yale University Press.

- Barkat, Amiram (2 April 2006). "Death camp escapee Vrba dies at 82", Haaretz

- Braham, Randolph L. (2000). The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary, Wayne State University Press, first published in 1981 in two volumes.

- Braham, Randolph L. (2011). "Hungary: The Controversial Chapter of the Holocaust," in Randolph L. Braham and William vanden Heuvel (eds.), The Auschwitz Reports and the Holocaust in Hungary, Columbia University Press.

- Brigham, Daniel T. (6 July 1944). "Two Death Camps Places of Horror; German Establishments for Mass Killings of Jews Described by Swiss", The New York Times.

- Chapman, Dick (24 January 1985). "Book 'An Artistic Picture': Survivor never saw actual gassing deaths", Toronto Sun.

- Conway, John (2005). "Escaping Auschwitz: Sixty years later", Vierteljahrshefte fuer Zeitgeschichte, 53(3), pp.&n,sp;461–472.

- Conway, John S. (1997). "The First Report about Auschwitz", Museum of Tolerance, Simon Wiesenthal Center, Annual 1, Chapter 7.

- Conway, John (2002). "The Significance of the Vrba–Wetzler Report on Auschwitz-Birkenau," in Rudolf Vrba. I Escaped from Auschwitz, Barricade Books.

- Dromi, Uri (30 January 2005). "Deaf Ears, Blind Eyes", Haaretz.

- Gilbert, Martin (1989). "The Question of Bombing Auschwitz," in Michael Robert Marrus (ed.), The Nazi Holocaust: The End of the Holocaust, Part 9, Walter de Gruyter.

- Gilbert, Martin (1990). Auschwitz and the Allies, Holt Paperbacks, first published 1981.

- Gilbert, Martin (1998). "What Was Known and When," in Michael Berenbaum and Yisrael Gutman (eds.), Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, Indiana University Press, first published 1994.

- Hilberg, Raul (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, first published 1961.

- Kárný, Miroslav (1998). "The Vrba and Wetzler report", in Berenbaum and Gutman, op cit.

- Kulka, Erich (1985). "Attempts by Jewish Escapees to Stop Mass Extermination", Jewish Social Studies 47(3/4), Summer/Fall, pp. 295–306.

- Klein, George (2011). "Confronting the Holocaust: An Eyewitness Account," in Braham and vanden Heuvel, op cit.

- Kranzler, David (2000). The Man Who Stopped the Trains to Auschwitz: George Mantello, El Salvador, and Switzerland's Finest Hour. Syracuse University Press.

- Linn, Ruth (2004). Escaping Auschwitz. A Culture of Forgetting. Cornell University Press.

- Linn, Ruth (2 February 2005). "Response to Dromi", Haaretz.

- Linn, Ruth (2011). "Rudolf Vrba and the Auschwitz reports: Conflicting Historical Interpretations", in Braham and vanden Heuvel, op cit.

- Lipstadt, Deborah (1993). Beyond Belief: The American Press & the Coming of the Holocaust 1933-1945. Free Press; first published 1985.

- Löb, Ladislaus (2009). Rezso Kasztner. The Daring Rescue of Hungarian Jews: A Survivor's Account. Random House/Pimlico; first published as Dealing with Satan: Rezso Kasztner's Daring Rescue Mission. Jonathan Cape, 2008.

- Martin, Douglas (7 April 2006). "Rudolf Vrba, 82, Auschwitz Witness, Dies", The New York Times.

- Martin, Sandra (8 April 2006). "Rudolf Vrba, Scientist and Professor 1924–2006", The Globe and Mail.

- Nueman, Elena (5 March 1990). "New List of Holocaust Victims Reignites Dispute over Figures", Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

- One World. "Rudolf Vrba Award", 8th international human rights documentary film festival.

- Pressac, Jean-Claude (1989). Auschwitz: Technique and operation of the gas chambers. The Beate Klarsfeld Foundation.

- Rees, Laurence (2006). Auschwitz: A New History. PublicAffairs.

- Sanderson, David and Smith, Lewis (1 April 2006). "Witness to Auschwitz horror dies at 82", The Times.

- Sakmyster, T.L. (1994). Hungary's Admiral on Horseback: Miklos Horthy, 1918–1944. Columbia University Press.

- Strzelecki, Andrzej (1998). "The Plunder of Victims and Their Corpses," in Berenbaum and Gutman, op cit.

- Świebocki, Henryk (ed.) (1997). London has been informed. Reports by Auschwitz Escapees. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

- Świebocki, Henryk (1998). "Prisoner Escapes" in Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp in Berenbaum and Gutman, op cit.

- Szabó, Zoltán Tibori (2011). "The Auschwitz Reports: Who Got Them, and When?" in Braham and vanden Heuvel, op cit.

- The Daily Telegraph (12 April 2006). "Rudolf Vrba".

- The Montreal Gazette (25 January 1985). "Witness lying to help Holocaust 'hoax' Zundel lawyer says".

- Tschuy, Theo (2000). Dangerous Diplomacy: The Story of Carl Lutz, Rescuer of 62,000 Hungarian Jews, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- vanden Heuvel, William J. (2011). "Foreword," in Braham and vanden Heuvel, op cit.

- van Pelt, Robert Jan (2002). The Case for Auschwitz: Evidence from the Irving Trial, Indiana University Press.

- van Pelt, Robert Jan (2011). "When the Veil was Rent in Twain," in Braham and Heuvel, op cit.

- Vrba, Rudolf (2002). I Escaped from Auschwitz. Barricade Books, 2002. First published as I Cannot Forgive by Sidgwick and Jackson, Grove Press, 1963; also published as Escape from Auschwitz: I Cannot Forgive.

- Vrba, Rudolf (14 April 2006). "The one that got away", extract from I Escaped from Auschwitz, The Guardian.

- Wetzler, Alfred (2007). Escape From Hell: The True Story of the Auschwitz Protocol, Berghahn Books, first published in 1963 as Co Dante nevidel under the pseudonym Jozef Lanik.

Further reading

- Auschwitz Protocols

- "The Vrba–Wetzler Report", Holocaust Education and Archive Research Team.

- Świebocki, Henryk (ed.) (1997). London has been informed. Reports by Auschwitz Escapees, Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

- Books by Vrba and Wetzler

- Lanik, Jozef (pseudonym of Alfred Wetzler) (1963). Co Dante nevidel, Bratislava.

- Lanik, Jozef (1967). Was Dante nicht sah, Frankfurt.

- Vrba, Rudolph and Bestic, Alan (1963). Escape from Auschwitz: I Cannot Forgive, Grove Press, 1964.

- Vrba, Rudolph and Bestic, Alan (1964). I Cannot Forgive, Bantam.

- Vrba, Rudolph and Bestic, Alan (1964). Factory of Death, Corgi Books.

- Vrba, Rudolph (2002). I Escaped from Auschwitz, Robson Books.

- Video

- Lanzmann, Claude (1985). Interview with Rudolf Vrba in Shoah, (part 1, part 2).

- PBS (2008). "Escape from Auschwitz".

- Linn, Ruth; Ben Ami, Y; Shalev, M (2005). "The escape from Auschwitz," part 1, part 2, the Academic Channel, 11 April.

- Miscellaneous

- Arendt, Hannah (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Viking.

- Bauer, Yehuda (1997). "Anmerkungen zum 'Auschwitz-Bericht' von Rudolf Vrba," Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Vol. 45.

- Berenbaum, Michael (14 October 2004). "Righteous Anger Fuels ‘Auschwitz’", Jewish Journal (review of Ruth Linn's Escaping Auschwitz: A Culture of Forgetting).

- Bilsky, Leora (Spring 2001). "Judging Evil in the Trial of Kastner", Law and History Review, 19(1).

- Cohen, Asher (1996). "The Holocaust of Hungarian Jews in light of the research of Randolph Braham," Yad Vashem Studies, Vol XXV.

- Czech, Danuta (ed.) (1989). Kalendarium der Ereignisse im Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau 1939–1945, Reinbek bei Hamburg.

- Davies, Matthew (23 January 2005). "Why didn't the Allies bomb Auschwitz?", BBC News.

- Dwork, Debórah and van Pelt, Robert Jan (2002). Holocaust: A History, W. W. Norton & Company.

- Dwork, Debórah and van Pelt, Robert Jan (1996). Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present, Norton

- Fatran, Gila (1994). "The Working Group", Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 8(2), pp. 164–201.

- Fraser, Christian (5 December 2006). "Vatican Holocaust claim disputed", BBC News.

- Gutman, Yisrael (1990). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Macmillan.

- Hecht, Ben (1999). Perfidy, Milah Press, first published 1961.

- Johnson, Pat (21 April 2006). "Israeli narrative omits Vrba", Jewish Independent.

- Laor, Yitzhak (26 December 2004). "Auschwitz, They Tell Me You’ve Become Popular", Haaretz (review of Ruth Linn's Escaping Auschwitz: A Culture of Forgetting).

- Lévai, Jenö (ed.) (1987). Eichmann in Hungary: Documents, Howard Fertig.

- Linn, Ruth (2001). "Naked victims, dressed-up memory: The escape from Auschwitz and the Israeli historiography", Israel Studies Bulletin, 16(2), Spring, pp. 21–25.

- Linn, Ruth (2003). "Genocide and the Politics of Remembering: The Nameless, the Celebrated and the Would-Be Holocaust Heroes", Journal of Genocide Research, 5(4), December pp. 565–586.

- Linn, Ruth (2004). "The Escape from Auschwitz: Why didn't they teach us about it in school", Theory and Criticism, 24:163–184 (in Hebrew).

- Linn, Ruth (13 April 2006). "Rudolf Vrba", The Guardian.

- Linn, Ruth (6 September 2006). "Against all hope: Escaping Auschwitz, escaping memory", Second Global Conference on Hope: Probing the Boundaries, Mansfield College, Oxford.

- Lungen, Paul (20 January 2005). "Auschwitz escapee hoped to warn Hungarian Jews", Canadian Jewish News.

- McMaster, Geoff (28 October 2003). "Holocaust survivor recounts days at Auschwitz", University of Alberta ExpressNEWS.

- Medoff, Rafael (2004). "The Unmentionable Victims of Auschwitz", The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, December.

- Medoff, Rafael (20 April 2006). "In memoriam: the man who exposed Auschwitz", The Jewish Tribune, 20 April 2006.

- Proudfoot, Shannon (21 March 2006). "Auschwitz escapee alerted world to horrors of the Holocaust," Ottawa Citizen.

- Rose, Hilary and Steven (25 April 2006). "Letter: Rudolf Vrba", The Guardian.

- The Jerusalem Post (1 April 2006). "Auschwitz escapee, 82, dies in Canada".

- UCL News (9 June 2006). "‘Trust and Deceit’ launched", University College London.

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. "Sources of Funding for UK & EU Applicants", Helena Vrbová Scholarship.

- Vrba, Rudolf (1992). "Personal Memories of Actions of SS-Doctors of Medicine in Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II (Birkenau)" in Charles G. Roland et al. (eds), Medical Science without Compassion, Past and Present, Hamburger Stiftung für Sozialgeschichte des 20.Jahrhunderts.

- Vrba, Rudolf (1996). "Die Missachtete Warnung. Betrachtungen über den Auschwitz-Bericht 1944," Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 44(1), pp. 1–24.

- Vrba, Rudolf (1998). "The Preparations For The Holocaust In Hungary: An Eyewitness Account" in Randolph L. Braham, Scott Miller (eds.), The Nazis' Last Victims: The Holocaust in Hungary, Wayne State University Press, pp. 55–102. Also published in Randolph L. Braham, Attila Pok (eds.) (1997). The Holocaust in Hungary. Fifty years later, Columbia University Press, pp. 227–285.

- Vrba, Rudolf (1998). "Science and the Holocaust", Focus, University of Haifa, an edited version of Vrba's address when he received his honorary doctorate.

- Vrba, Rudolf (14 April 2006). "The one that got away", extract from I Escaped from Auschwitz, The Guardian.

- Yad Vashem. "April 25: Blood for trucks".

|