Royal Castle, Warsaw

| Royal Castle | |

|---|---|

| Zamek Królewski | |

View from the Castle Square | |

Location within Poland | |

| General information | |

| Type | Castle residency |

| Architectural style | Mannerist-early Baroque |

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Country | Poland |

| Coordinates | 52°14′52″N 21°00′51″E / 52.24778°N 21.01417°E |

| Construction started | 1598,[1] 1971[1] |

| Completed | 1619,[1] 1984[1] |

| Demolished |

1655–1656 (Swedish Army),[1] 10 – 13 September 1944 (German Army)[1] |

| Client | Sigismund III Vasa |

| Owner |

Władysław IV Vasa John II Casimir Michael Korybut Wiśniowiecki John III Sobieski Augustus II the Strong Stanisław I Leszczyński Augustus III Stanisław II Augustus Polish government (last owner) |

| Height | 60 metres |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Giovanni Battista Trevano |

| Website | |

| Official Website | |

The Royal Castle in Warsaw (Polish: Zamek Królewski w Warszawie) is a castle residency and was the official residence of the Polish monarchs. It is located in the Castle Square, at the entrance to the Warsaw Old Town. The personal offices of the king and the administrative offices of the Royal Court of Poland were located there from the 16th century until the Partitions of Poland.

The Constitution of 3 May 1791 was drafted here by the Four-Year Sejm.[2] In the 19th century, after the collapse of the November Uprising, it was used as an administrative centre by the Tsar. Between 1926 and World War II the palace was the seat of the Polish president, Ignacy Mościcki. After the devastation done by Nazis during the Warsaw Uprising, the Castle was rebuilt and reconstructed. In 1980, the Royal Castle, together with the Old Town was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Today it is a historical and national monument, and is listed as a national museum.[3]

History

At the end of the 13th century, during Duke Conrad II of Mazovia's reign, the wooden-earthen gord called Smaller Manor (Latin: Curia Minor) was built. The following duke, Casimir I, decided to build here the first brick building at the burg-city's area, the Great Tower (Latin: Turris Magna).[4] Between 1407 and 1410, Janusz I of Warsaw built a multi-story Gothic brick castle, called Bigger Manor (Latin: Curia Maior). From 1526 (when the last Masovian Dukes – Stanislaus I and Janusz III died) it became the Royal Residence.[4]

Between 1548–1556 the castle was the residence of Queen Bona Sforza, wife of Sigismund I the Old.[4] The following Polish monarch, Sigismund II Augustus, between 1568–1572, began the building's reconstruction project. For example, the Renaissance Royal House was added to the Bigger Manor as part of Giovanni's Battista di Quadro's project.[4] Jakub Parr, an architect from Silesia, took part in this works as well.

In 1595, King Sigismund III Vasa made a decision to expand the castle to make it more suitable for public functions. Reconstruction in the Mannerist-early Baroque style was done between 1598–1619.[4] The Castle was enlarged and given its present five-sided shape, with an imposing Mannerist-early Baroque elevation facing the town, and a high tower known as the Sigismund's Tower.

At the time of the Deluge between 1655–1656, the castle was plundered. In 1656, during the Swedish and German siege of Warsaw, a shot hit Sigismund's Tower spire, which caused it to break and collapse into the castle's courtyard.[5]

When the Swedish wars, and the tremendous devastation caused thereby, came to an end, the Castle was rebuilt during the reigns of the Polish kings Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki and John III Sobieski.[4]

During the Great Northern War, the Castle suffered from Swedish occupation (they barricaded the castle and kept their horses in the opera hall. Germans shelled it from the Praga bank and Krakowskie Przedmieście. The castle was plundered by Swedish, German and Russian troops. Tsar Peter I of Russia took the paintings and other artifacts that were preserved at the castle to St. Petersburg.

In the first half of the 18th century, when first Augustus II the Strong and then Augustus III, of the Wettin family from Saxony, were elected to the throne of Poland, there were several attempts at to rebuild the castle, but these came to nothing. In 1737, under hire from the Polish Parliament, the Italian architect Gaetano Chiaveri designed a new wing facing the Vistula.[4] It was built between 1741 and 1747, under the supervision of a Polonised Italian, Antonio Solari. This was an excellent design which harmonized extremely well with the older parts of the castle buildings.

During the reign of Stanisław Augustus Poniatowski, the last Polish monarch, from 1764 to the third partition of Poland in 1795, the Royal Castle went through a period of greatness.[4] The allocated money from the royal budget as well as the patronage which the king granted artists and the education and artistic taste of the ruler himself allowed for one of the most interesting reconstruction projects of the castle. Quite a few projects were carried out, which were designed by, among others, French architect Victor Louis,[4] Johann Christian Kamsetzer or Efraim Szreger. The baroque-classical interior renovation was carried out on the basis of Jakub Fontana's and Domenico Merlini's projects. From 1773 the floor was thoroughly refurnished and the inside was decorated (D. Merlin and J.Ch. Kamsetzer's projects), for example new royal apartments, such as The Royal Chapel, The Knight Hall (otherwise known as The National Hall) and The Ballroom (Great Assembly Hall) were built.[5] The successful changes made by the king that took place inside the Castle had a very characteristic Polish style and a high artistic level. A new Royal Library was built, running along the right wing of the Copper-Roof Palace (included in 1776 to the group of castle buildings) measuring 56 × 9 m.

On 3 May 1791, Sejm passed a constitution at the Royal Castle in Warsaw.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Castle was the residence of Frederick Augustus, Duke of Warsaw and King of Saxony. After the collapse of the Polish Insurrection of 1830–1831, the Castle was the seat of the Governors of the Polish Kingdom.

Many reconstruction projects were done in the 19th century and were the work of Polish architects, such as Adam Idźkowski and Jakub Kubicki. Idźkowski's project of 1843 was a reconstruction of the Royal Castle using decorative forms borrowed from the gothic, Renaissance and Empire architecture. It planned the building of a third floor with seven different-sized towers, with attics decorated with eagles and antique statues. On the Zygmuntowska and Władysławowska towers, the metal roof domes were meant to be removed and replaced with terraces, surrounded by balustrade. On the Vistula side, on the Saxon elevation, Idźkowski planned to put up antique style reliefs, underneath the frieze of the 3 risalits. And later, on the façade of the 3rd floor Corinthian pilasters. Horizontal rustic belts and iron balconies were meant to decorate both of the Royal Castle's elevation as well as the Copper-Roof Palace. This project, characteristic for its brave architectural forms, was the answer to the new trend of using historical forms in architecture (as opposed to Kubicki's project 20 years prior, stating moderation of forms based on past works of royal architects carrying out projects on the Royal Castle).

At the time of the Polish national insurrection, in 1863, the square in front of the castle was the scene of patriotic demonstrations that ended in much bloodshed.

More restoration work began in 1915 and accelerated after the end of World War I, when Poland regained its independence in 1918 following 123 years of partitions. The Peace of Riga in 1921 let Poland retrieve some of the Castle collection from the USSR.[5] The 1920s conservation and reconstruction works were supervised by architect and conservator Kazimierz Skórewicz. In 1928, he was replaced by another architect, Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz. Since 1926 the Royal Castle was the Polish president's residence.

In September 1939 the Castle burnt after the German bombing.[5] During the subsequent occupation the Castle was plundered. German scholars, including Professor Dagobert Frey and Dr Joseph Mühlmann, took an active part in the work of destruction.[6] The National Museum was allowed to keep only a few pieces of equipment to describe the losses and secretly document them with photographs. Art historian Stanislaw Lorentz was the one who supervised this process.[5] On Hitler's orders, the Castle was due to be blown up at the beginning of 1940. The bomb unit drilled a number of holes to put dynamite in[4][7] however, it was not (because of the protest of Italy) until after the Warsaw Uprising when this order was carried out.

In the years 1945-1970, the Communist authorities delayed making a decision on whether to rebuild the Castle. The decision to do so was taken in 1971. Funds for the rebuilding of the Castle, which took until 1980, were provided by the community.

In 1984 the reconstructed interiors were opened to the public.

Since 1995 work has been undertaken on the conservation of the Kubicki Arcades (finished in 2009 [8]) and the reconstruction of the gardens. These works are completed, the refurbishing of the Tin-Roofed Palace was finished in 2010,[9][10] thus the rebuilding of the Royal Castle complex has been nearly finalized: the Castle Gardens remain in reconstruction phase, with a finished project and works to begin soon.[11]

The Castle today

The imposing façade, built of brick is 90 m long and faces the Castle Square.[12] At each end of the façade stands a square tower with a bulbous spire. The Sigismund's Tower is located in the centre of the main façade, flanked on both sides by the castle. This huge clock tower of 60 m in height designed in the sixteenth century, has always been a symbol of the Polish capital and source of inspiration for the architects of other buildings in Warsaw. Nowadays, the Castle serves as the Museum and is subordinated to the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. Many official visits and state meetings are also held in the Royal Castle.

Interior

The interior consists of many different rooms, all painstakingly restored with as much original exhibits as possible after the destruction of the Second World War.

- The Jagiellonian Rooms

These rooms, which belonged to the residence of Sigismund Augustus, are now host to a number of portraits of the Jagiellon dynasty, a royal dynasty originating in Lithuania that reigned in some Central European countries between the 14th and 16th century.[13] In 2011 the Jagiellonian Rooms were re-arranged to house the modern Gallery of Painting, Sculpture and Decorative Arts.[14]

- The Houses of Parliament

From the 16th century onwards, Polish democracy started here.[15] In 1573, amendments to the constitution of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were written here, with great religious tolerance. Also, during the Deluge in 1652, the liberum veto was established in these rooms, although not carried out until 1669. In 1791, the May Constitution, Europe's first modern codified national constitution as well as the second-oldest national constitution in the world, was drafted here. The decorations in the room are replicas of the originals by Giovanni Battista di Quadro.[15]

- The Royal Apartments

In these apartments, King Stanisław Augustus Poniatowski lived. They consist of the Canaletto room, in which several painted views of Warsaw are on display.[4] These were not painted by Canaletto, but rather by his nephew, Bernardo Bellotto also called il Canaletto. Jean-Baptiste Pillement worked between 1765–1767 on one of his largest projects, the wallpaper.[4] Domenico Merlini designed the adjacent Royal Chapel in 1776.[4] Nowadays, the heart of Tadeusz Kościuszko is kept here in an urn. The Audience Rooms are also designed by Merlini, with four paintings by Marcello Bacciarelli on display. Andrzej Grzybowski took care of the restoration of the room, that included many original pieces.

- Lanckoroński Collection

In 1994 Countess Karolina Lanckorońska donated 37 pictures to the Royal Castle. Collection includes two paintings (portraits) by Rembrandt: The Father of the Jewish Bride (also known as The Scholar at the Lectern) and The Jewish Bride (also known as The Girl in a Picture Frame)[16] both originally in the Stanisław Augustus Poniatowski collection.[17]

- Artwork

-

The moral fall of humanity, Jan de Kempeneer, 1548–1553

-

Prince Władysław Vasa, Jakob Troschel, 1605

-

Queen Constance of Austria, Jakob Troschel, 1624

-

Art Cabinet of Prince Władysław Vasa, Etienne de la Hire, 1626

-

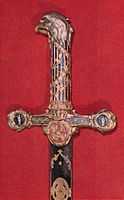

Ceremonial sword of the Saint Stanislaw’s Order, 1764

-

Portrait of Pélagie Sapieżyna-Potocka, Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1794

- The Interior of the Castle

-

Old Chamber of Deputies

-

Old Audience Room

-

Canaletto Room

-

Great Assembly Hall

-

Marble Room

-

Knight's Room

-

The Throne Room

Copper-Roof Palace

The Copper-Roof Palace has since 1989 been a branch of the Royal Castle Museum.[18] The palace is contiguous with Warsaw's Royal Castle, and down a slope from the Castle Square and Old Town. It now hosts a collection of oriental carpets and other oriental decorative art, donated to the museum by Mrs. Teresa Sahakian.[19] The collection comprises 579 items, 562 of which are textiles.[20]

Curiosities

- On 24 May 1829 in the Royal Castle's Senator's Hall, Nicholas I of Russia was crowned King of Poland.[21][22]

- On 5 November 1916, the Act of 5 November was announced in the Grand Hall.[23]

- On 23 April 1935, the April Constitution was signed in the Knight Hall.[12]

- Stanisław Augustus Poniatowski's regalia are kept in the Royal Chapel. These are the Order of the White Eagle, the ceremonial sword of the Saint Stanisław's Order and aquamarine sceptre.[4]

- The insignia of presidential power are also stored in the Castle- the stamp of the President, the Jack of the President of the Republic of Poland and national documents, which Ryszard Kaczorowski gave to Lech Wałęsa on 22 December 1990.[24]

- Many of the Polish legends are connected with the Royal Castle. According to one of them in 1569 the King Sigismund Augustus, who was in mourning after death of his beloved wife Barbara Radziwiłł, asked the renowned sorcerer Master Twardowski to evoke her ghost.[25][26] The experiment was successful with support of a magic mirror, which today is kept in the Węgrów Cathedral.[25] Despite that some people suspected that it was not the Queen's ghost but closely resembling her king's mistress Barbara Giżanka and the whole event was set up by Giżanka's accomplice Mikołaj Mniszech, king's chamberlain.[26]

Chicago replica

In 1979, the historic Gateway Theatre in the Jefferson Park community area of Chicago was purchased by the Copernicus Foundation with the intention of converting it into the seat of the Polish Cultural and Civic Center. Because of the building's historical significance, its interior was kept intact while the exterior was remodelled and a Neo-Baroque clock tower was added to give it the resemblance of the Royal Castle in Warsaw.[27] It is a visual tribute to Chicago's large Polish populace, the largest such presence outside of the Republic of Poland.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Castle Warsaw. |

- Castle Square

- St. John's Cathedral

- Zygmunt's Column

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "History of Royal Castle – official website". 16 May 2010.

- ↑ "Sale Sejmowe". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 18 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Pomnik Historii i Kultury Narodowej". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 22 Jul 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 "Zamek Królewski w Warszawie (The Royal Castle in Warsaw)". www.dziedzictwo.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 18 Jul 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Historia". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 18 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Royal Castle in Warsaw". www.castles.info. Retrieved 18 Jul 2008.

- ↑ Peter K. Gessner. "Warsaw's Royal Castle and its destruction during the Second World War". University at Buffalo. Retrieved 8 Feb 2008.

- ↑ Arkady Kubickiego w Zamku Królewskim otwarte, gazeta.pl z 31 marca 2009

- ↑ The Castle, official website

- ↑ Monika Kuc (14 July 2011). "Royal Castle, Tin-Roofed Palace,official website".

- ↑ "Zamek Królewski w Warszawie - Muzeum - Strona główna". zamek-krolewski.pl. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Warszawa Zamek Królewski". www.zamkipolskie.com (in Polish). Retrieved 22 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Pokoje Dworskie". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 18 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Galeria Malarstwa, Rzeźby i Sztuki Zdobniczej". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Dawna Izba Poselska i sale sąsiednie". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 18 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Galeria Lanckorońskich". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 18 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Historia dwóch obrazów". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 18 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Remont i przebudowa pałacu Pod Blachą". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 23 Mar 2009.

- ↑ "Wystawa kobierców wschodnich". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 23 Mar 2009.

- ↑ "Fundacja Teresy Sahakian". www.zamek-krolewski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 23 Mar 2009.

- ↑ "Historia Repliki Polskich Insygniów Koronacyjnych". www.replikiregaliowpl.com (in Polish). Retrieved 22 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Insygnia koronacyjne Królów Polski (1025–2003)". www.polskiedzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 22 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Akt 5 listopada 1916 roku". dziedzictwo.polska.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 22 Jul 2008.

- ↑ "Wydarzenie". www.prezydent.pl (in Polish). 2 Nov 2004. Retrieved 22 Jul 2008.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Jan Mielniczka (29 Oct 2007). "Legendy o Węgrowie". www.wegrow.com.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 19 Mar 2009.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Franciszek Kucharczak. "Duchotwórca". www.maly.goscniedzielny.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 11 Feb 2010.

- ↑ Northwest Chicago Historical Society. Newsletter – January 2005; Number 1 www.nwchicagohistory.org

Bibliography

- Lileyko Jerzy (1980). Vademecum Zamku Warszawskiego (in Polish). Warsaw. ISBN 83-223-1818-9.

- Stefan Kieniewicz, ed. (1984). Warszawa w latach 1526–1795 (Warsaw in 1526–1795) (in Polish). Warsaw. ISBN 83-01-03323-1.

External links

- Royal Castle website

- Virtual tour

- Castles.info—Royal Castle in Warsaw — history and pictures.

- Warsaw Castle

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||