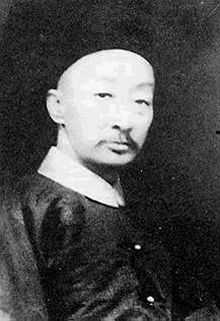

Ronglu

- This is a Manchu name; the surname is Guwalgiya.

| Guwalgiya Ronglu 瓜爾佳·榮祿 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Viceroy of Zhili | |

| In office 15 June 1898 – 28 September 1898 | |

| Preceded by | Wang Wenshaw |

| Succeeded by | Yuan Shikai |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 April 1836 |

| Died | 11 April 1903 (aged 67) |

| Spouse(s) | Wanzhen[1] |

| Relations | Guwalgiya Changshou (father) Xuantong Emperor (grandson) |

| Children | Guwalgiya Youlan |

| Occupation | Grand Secretariat |

| Posthumous name | Wenzhong 文忠 with the title of 1st class baron |

Guwalgiya Ronglu (Guwalgiya Jung-lu; Chinese: 瓜爾佳·榮祿), commonly known mononymously as Ronglu (Jung-lu; Chinese: 荣禄; Wade–Giles: Jung2-lu4; 6 April 1836 – 11 April 1903) was a Manchu statesman and general during the late Qing dynasty. Born into the powerful Guwalgiya clan of the Plain White Banner in the Eight Banners, he was cousin to Empress Dowager Cixi.[2] He served in a number of important positions in the Imperial Court, including the Zongli Yamen and the Grand Council, Grand Scholar, Viceroy of Zhili, Beiyang Minister, Minister of Board of War, Nine Gates Infantry Commander, Wuwei Troop Commander that safeguard the military security of the Forbidden City.[3]

Life

Ronglu was born on 6 April 1836. He was the son of Guwalgiya Changshou (瓜爾佳長壽). Ronglu's grandfather, Guwalgiya Tasiha (瓜爾佳塔斯哈), had served in Kashgar as an official.

Before Cixi's marriage as a concubine into the royal family, Ronglu was rumored to have had a love relationship with Cixi.[4] During Cixi's tenure as regent of the Qing Dynasty, Ronglu became one of the leaders of Cixi's conservative faction at the imperial court, and opposed Kang Youwei's Hundred Days' Reform in 1898. Cixi always remembered her cousin's support for her, even when they were young, and rewarded him by allowing his only surviving child, his daughter Youlan, to marry into the imperial clan.

Through his daughter's marriage to Zaifeng, Prince Chun, Ronglu is the maternal grandfather of the Xuantong Emperor.

Professional career

At 1894 after First Sino-Japanese War was appointed Peking Land Troop Commander (Chinese:步军统领), at 1895, he was appointed minister of Zongli Yamen, minister of Board of War (Chinese:兵部尚书) and Peking Land Troop Commander. During the Boxer Rebellion, Ronglu was the commander of Wuwei Middle Troop (Chinese:武卫中军), providing military security for the Forbidden City.

At 1898, Ronglu was appointed Grand Scholar (Chinese:协办大学士), Viceroy of Zhili, Beiyang Minister (Chinese:北洋大臣), Minister of Grand Council and Minister of Board of War (CHinese:兵部), coordinating between Dong Fuxiang, Nie Shicheng, Song Qing and the Yuan Shikai Beiyang Army, and creating Wuwei Troop (Chinese:武卫军), then appointed Nine Gates Infantry Commander. When Empress Dowager and Guangxu Emperor escaped to Xian during the invasion of the Eight Nation Alliance, Ronglu was ordered to stay in Peking to safeguard the Peking City and the Forbidden City.[5][6]

Boxer Rebellion

On Day Nineteen of May (lunar calendar) 1901, a total of five decrees were issued by the Empress Dowager. Decree No.1 ordered Ronglu to "command various Imperial soldiers, plus the Peking Field Force, the Tiger Gods Division, with cavalry, in addition of Wuwei Troop, to suppress these bandits, to intensify searching patrol; to arrest and execute immediately all criminals with weapons who advocate killing.". Decree No.4 of the same day ordered Ronglu to "send an efficient troops of Wuwei Middle Troop swiftly, to the Peking Legation Quarter, to protect all the diplomatic buildings."[7]

In 1899, with the approval of Empress Dowager, Ronglu began to build the first modern infantry military force of the Manchu Empire. During the war with the Eight Nation Alliance, Wuwei Troops commanded by Dong Fuxiang and Nie Shicheng and Ronglu himself suffered heavy casualties and were disbanded.

Ronglu did not want to antagonize the Empress Dowager, but was not sympathetic with the Boxers. Like the leading governors in the south, he felt that it was folly for China to take on all of the great powers at once. When Dong Fuxiang's Muslim troops were eager to attack the legations, Ronglu made sure that the siege was not pressed home.[8] The Manchu prince Zaiyi was xenophobic and was friends with Dong Fuxiang. Zaiyi wanted artillery for Dong Fuxiang's troops to destroy the legations. Ronglu blocked the transfer of artillery to Zaiyi and Dong, preventing them from destroying the legations.[9] When artillery was finally supplied to the Imperial Army and Boxers, it was only done so in limited amounts.[10]

Ronglu also hid an Imperial Decree from General Nie Shicheng. The Decree ordered him to stop fighting the Boxers. General Nie continued to fight against the Boxers and killed many of them at a time when the Allied armies were making their way into China. Ronglu also ordered Nie to protect foreigners and save the railway from the Boxers.[11] Ronglu had effectively derailed the Chinese effort to take the legations, and as a result, saved the foreigners and Chinese within them. He was shocked that he was not welcome after the war; however, the Allies did not demand that he, unlike Dong Fuxiang, be punished.[12]

In 1963, he was portrayed by Leo Genn in the movie 55 Days at Peking.

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Imperial Decree of declaration of war against foreign powers

- Imperial Decree on events leading to the signing of Boxer Protocol

- Peking Field Force

References

- Hummel, Arthur William, ed. Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (1644–1912). 2 vols. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1943.

- ↑ Initially Ronglu's concubine, she became his official wife when Ronglu's first wife died.

- ↑ Woo, X.L. Empress Dowager Cixi: China's Last Dynasty and The Long Reign of a Formidable Concubine. p. 17

- ↑ Woo, X.L. Empress Dowager Cixi: China's Last Dynasty and The Long Reign of a Formidable Concubine. p. 17

- ↑ Old Buddha, Princess der Ling.

- ↑ http://www.qingchao.net/lishi/ronglu-dongnanhubao/荣禄与东南互保

- ↑ http://www.qingchao.net/lishi/ronglu-2/ 论晚清重臣荣禄

- ↑ http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Imperial_Decree_on_Day_Nineteen_of_May(lunar_calendar)#Decree_3Imperial

- ↑ Paul A. Cohen (1997). story in three keys: the boxers as event, experience, and myth. Columbia University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-231-10650-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ X. L. Woo (2002). Empress dowager Cixi: China's last dynasty and the long reign of a formidable concubine : legends and lives during the declining days of the Qing Dynasty. Algora Publishing. p. 216. ISBN 1-892941-88-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Stephen G. Haw (2007). Beijing: a concise history. Taylor & Francis. p. 94. ISBN 0-415-39906-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Lanxin Xiang (2003). The origins of the Boxer War: a multinational study. Psychology Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-7007-1563-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Peter Fleming (1990). The Siege at Peking: The Boxer Rebellion (illustrated ed.). Dorset Press. p. 228. ISBN 0-88029-462-0. Retrieved 1-9-2011. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)

|